Leon Battista Alberti architetto, A cura di Giorgio Grassi e Luciano Patetta Banca CR Firenze – Edizioni Scala, Firenze 2006 (pp. 318, s.i.p.)

The Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze has dedicated a book to Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), over 600 years after his birth. Edited by two professors of Milan Polytechnic, Grassi and Patetta, the book is divided into five parts, each containing a number of illustrated essays. Grassi begins with an introduction to the relationship between Alberti and Rome’s architecture, stressing the personal commitment as a designer that bound Alberti to his work. He describes the “master” as a learned philosopher-architect who was aware of the difficulties and responsibilities of his work. In terms of the intelligence, complexity and wealth of constructional solutions, he cites Alberti’s restoration of the Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome as an example of preservative action that clearly interprets a construction typology; the Pantheon and other buildings of Rome.

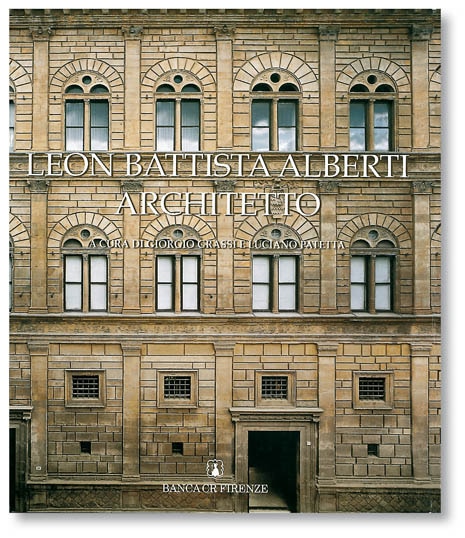

In his second piece, Grassi speaks o0f Alberti’s intellectual approach to the profession that led him to be a treatise writer: the architect is an idealised, perhaps non-existent figure but with a very clear sense of his constructive role in driving reality. Alberti is compared to Loos for his way of theorising style and for being more of a human and cultural model than technical one. The third essay analyses Alberti’s design method and considers the facade of Palazzo Rucellai, which was his most completely designed project. At the beginning of his chapters and in the text, Grassi repeats passages from De re aedificatoria, commenting on them and using them to underpin his understanding of architecture. In the name of Alberti and of Rome’s architecture, he reasserts his theory on modernity and realism in architecture, “on the impossibility, the total inadequacy and unacceptability of architectural renewal based on that experience”.

He ends by recalling other examples from subsequent eras that can be considered theoretical and operational references: Bernini, Boullé, Fischer von Erlach, Schinkel and then Hilberseimer, Loos and Tessenow. As a theoretician of contemporary architecture, he gives us insight into the continuity of the scientific approach and the reasoning behind the methods and criteria for carrying out and designing a construction. Grassi establishes a parallel interpretation between the architecture of today and that of the past, bringing great relevance to the “treatises” (of which Alberti was the leading Renaissance writer) and “trends”, today the definition used for operations based on the search for a style, rational method and self-expression that goes against the strictly functionalistic design approach.

Luciano Patetta speaks, on the other hand, of Alberti’s humanistic, literary and technical training, describing him as an erudite figure of intellectual commitment. He lists his treatises and dwells on De re aedificatoria, its structure, objectives and editorial success. He also speaks of his life and experiences in Rome, Florence, Rimini and Mantua. He comments on his architectural work and reminds us of his influence on Italian Renaissance design, works and architects. Alberto Giorgio Cassani – a scholar and professor of the history of contemporary architecture and restoration – speaks of the relationships and intellectual affinities between Alberti and the Prince of Rimini, Sigismondo Malatesta, which led to the creation of the Tempio Malatestiano.

He also provides an account of its design process plus a detailed description and careful graphic reconstruction. Riccardo Pacciani – a historian and professor in Florence – writes of Alberti’s period in Florence and his relationships with contemporary artists and intellectuals. He then gives a detailed description of the constructions attributed to him (from Palazzo Rucellai to the facade of Santa Maria Novella, the Cappella Rucellai in San Pancrazio and the Rotonda della Santissima Annunziata) with the support of fine photographic records. Lastly, Paolo Carpeggiani – a historian and professor in Milan and Mantua – speaks of the Gonzaga family, their court and Alberti’s experience in Mantua, where he ended his career as an architect.

The essay speaks of Marchese Ludovico’s desire for urban renewal, the idea that led him to transform Pienza for Pius II, and also describes Alberti’s works of San Sebastiano and Sant’Andrea. The fine reproduction of Renaissance works as references to the text (pictures, drawings and architecture) makes this book a historical compendium, as well as a theoretical treatise on design, partly thanks to what Grassi calls a consistent aid to contemporary working. All the beautiful illustrations come from the Archivio Scala in Florence, an authoratative source of illustrations on the visual arts. Roberto Gamba Architect