Il tempo e l’architetto. Frank Lloyd Wright e il Guggenheim Museum, Francesco Dal Co Electa, Milano 2004 (pp. 168, € 29,00)

Appearance is not deceptive. In this small, richly illustrated monograph dedicated to New York’s Guggenheim Museum, Francesco Dal Co brings together a series of strictly topical questions on Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece consigned to the history of architecture in October 1959 (six months after the master’s death).

This book deals with the relations between art and architecture, the complex relations between client, architect and the social and economic context, the historiographic problems inherent in a building’s symbolic value and the reconstruction of its specific structural elements, the topic of the contemporary museum – “where the relics of history’s castaways find refuge” – and above all the question of time, the “great constructor”.

In front line is the historical interpretation of the Guggenheim Museum’s design and construction phases: from 29 June 1943, the day when eighty-two-year-old Solomon R. Guggenheim entrusted to seventy-six-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright the task of designing the venue to exhibit his own modern art collection, to 21 October 1959, the day of the building’s inauguration, celebrated in memory of the two protagonists. In the sixteen years between these two dates there is the meeting, or rather the collision between the architect’s desire to build a “spring” capable – according to a provocative statement by Wright – of rising up above the ground of New York in the event of bombardment, and the client’s intention aimed at the more comforting image of a “temple”, a “church”, a “house” of modern art open to the public.

Two other protagonists enter the story here: the German baroness Hilla Rebay, painter and consultant of Guggenheim and James Sweeney, who not without controversy replaced her as museum director in 1952. Both, Dal Co explains, had conflictual relationships with the architect. Rebay’s formation was closer to the “Bauhausers” (a scarcely amiable term used to define the “left wing modernists” who emigrated to America), and from the outset underlined an ill-concealed hostility towards the design, accusing Wright of planning a “monument in honour of himself”.

The “fanatical” Sweeney was no less oppositional with his exhaustive attempts to block the museum’s construction, even encouraging a very critical appeal from artists published in the influential New York Times in 1956. Nonetheless, neither of them knew that, as Luis Carré wrote (an art dealer and buyer of Aalto) from New York commenting on the complex affair, “there is a special angel protecting great architects”.

So was the American master’s “majestic old age” protected by an angel? It cannot be excluded, reading in this book the methods Wright employed in skilfully overcoming the many difficulties standing in the way of his idea’s fulfilment, perfecting the design, writing combative letters and personally overseeing the construction site. In March 1956, when the New York Building Commission granted permission for the construction of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s museum, on Fifth Avenue opposite Central Park, Wright was eighty-eight years old. For the occasion he moved to the famous suite in the Hotel Plaza in New York, which he had furnished and was renamed Taliesin the Third or Taliesin East. For him this adventure had a very special meaning.

The celebrated prophet of “organic architecture” and the Living City, the valorous adversary of the metropolis and skyscrapers descended on New York, the “city where architecture does not exist”, to construct his overturned pyramid. Dal Co underlines Wright’s effort directed at denying “any chance of confrontation and dialogue between the new building and the environment into which it which it will be inserted”.

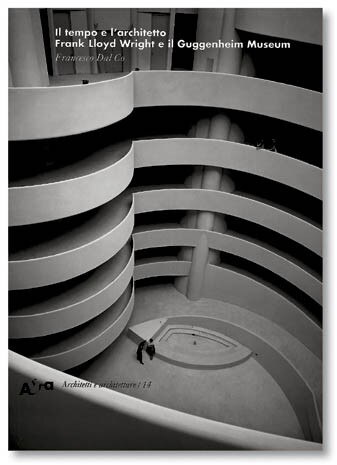

Starting from the design of the version of the project with the inverted spiral where the words “Ziggurat-Taruggiz” appear at the bottom, he investigates the construction solutions that led the architect to compose a completely white “monolith without joints” open to the sky. Its volume is dense with surprising plastic and spatial effects and appears suspended in midair or embedded in the ground of Manhattan depending on the viewpoint. To take a step backwards, in 1943, the year of the Guggenheim commission, Wright published the new monumental edition of An Autobiography with Horizon Press, containing a significant piece against skyscrapers: “A free and democratic country, as our forefathers intended the United States to be, should guarantee individual freedom, within his limits. (…)

Why not give him a horizontal plane that expands parallel to the ground, rooting every structure to the ground? This is a real capitalist system, a pyramid with a summit and a wide base on the ground. This new sense of internal space, in man as in the buildings or lifestyles that model themselves around it, must open up to the light of the sun, the sky and the air otherwise we will have communist manpower in place of democratic citizens full of initiative in a country that offers ample possibilities to individual initiative.”

The Ziggurat of the project’s first version might come from this conception, which Wright transformed into an overturned spring, a Taruggiz. As Dal Co explains, this was to “provoke a disconcerting effect” in New York’s uniform urban grid. He highlighted the unnatural increase in the weight of construction directed towards the sky, but that on the inside, after being opened up to the sky, significantly returns to the ground, and “spends itself on the ground next to a lentiform waterhole”.

The museum visitor therefore climbs the flights of stairs of art, looks up towards the vault enclosing the space with twelve ribs like a clock face, but looking over the invaded interior (because any view of Central Park is precluded), apart from the miniscule spots of movement of the co-visitors, he observes a “moist eye” that watches him and shows him the way back. So in the “neither absolute, nor equal nor unequivocal” passing of time between the year of the Guggenheim museum’s commission (1943) and the year of its inauguration (1959), Wright made his language reversible: the Ziggurat is overturned, but its base unequivocally returns to the ground. The historian, however, does not indicate any happy ending. Wright’s “barbaric” spring, alien and hostile to the city in which it sits, has been transformed over time into a “reassuring spectacle”.

Like a work of art in a museum, its prodigious form that simultaneously aroused wonder and violent criticism (a “gigantic pillbox” according to Mumford), is today a stranded piece of wreckage in New York, on Fifth Avenue opposite Central Park. It was the birthplace in 1959 of “a curved wave that never breaks”.

Is it one of modern architecture’s many failures? No, more simply the wave broke along the “wall of time” that – as Dal Co writes paying homage to Jünger – took back possession of the old architect after accompanying him in the construction of his masterpiece, entrusting him “temporarily to the care of history’s misfortune”.

Federico Bucci Professor of History of Contemporary Architecture at the Polytechnic of Milan