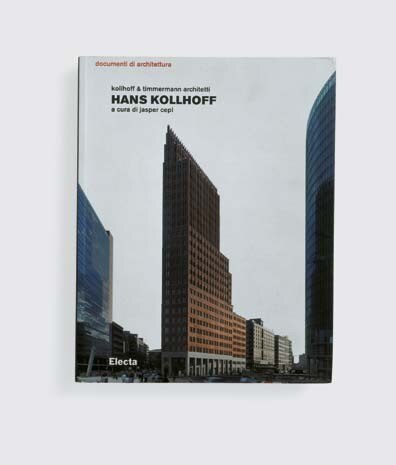

Kollhoff & Timmermann architetti

Hans Kollhoff

A cura di Jasper Cepl Electa – documenti di architettura - Milano, 2003 (pp. 440, € 68,00)

Hans Kollhoff, who partnered with Helga Timmerman in 1984, gained international stature with his housing designs for IBA, one of the best German projects in the 1980s. Now Electa has published a monograph devoted to his oeuvre. Jasper Cepl’s publication illustrates Kollhoff’s entire career, from his studies with Egon Eiermann at the University of Karlsruhe to his move to Vienna with Hans Hollein and his decision to follow Osvald Mathias Ungers to Cornell University.

Cornell, where Colin Rowe hired him to teach, is where Kollhoff’s education and interests consolidated under the influence of Aldo Rossi and Robert Venturi. But his training (inevitably) developed out of the famed CIAM congress in Otterlo, a critical heritage poised between contextualism, the morphological approach, the comeback of typology and the critique of ingenuous functionalism. Kollhoff maintains that it was in America that he began to profoundly understand European cities. This comprehension engendered a greater interest in the quest and return to urban traits eroded by modern architecture, such as that of the 1920s.

He was at Cornell from 1975 to 1978; these ‘happy circumstances’ helped him to find Ungers and Rowe, a meeting that eventually gave birth to the City of Composite Presence (the architect was engrossed in their disagreement over the school’s teaching programme). ‘It is a city of isolated buildings and public spaces thickening into a texture. I think it is a modern city that supports its incapacity to produce a texture in its slight inclination to conventions, but it uses historic stereotypes for its images’, he remarked.

This image kicks off the volume, though this should not imply that the project was inconsequential juvenilia. Likewise, the illustration and the commentary are thought-provoking: they hark back to Tafuri’s reading of Piranesi’s Roman Drill Ground. Kollhoff’s collage is too similar to Piranesi’s famous illustration for us to avoid comparing their meanings, but they appear to be on opposite trajectories. Kollhoff’s has a positive value, a reciprocal exchange between the object and texture; for Tafuri, however, modernism’s failure is compensated by falling back on a historical image: ‘A shapeless heap of fragments bumping against one another’. The radical dissolution of form takes place on such a scale that it influences the entire urban structure.

As Tafuri puts it, another historicist cover remains. But this surface hides, at first glance, the overall outcome of the effort – the fact that ‘this mass of typological inventions purposely excludes the identification of the city as a complete formal structure. The clash of organisms dissolves even the remotest memory of towns as the place of Form’ (Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labyrinth, 49). Paradoxically, the unbridled typological proliferation produces its negation, the proof that typology cannot organize an urban organism. Instead, architectural objects appear to float on something that is no longer a place – one of Foucault’s heterotopias.

Yet the Drill Ground can have two significances. As a critique of the excessive typological experimentalism of the 18th century, it would also have provided a moral warning. However, the consequence is not dialectical union; instead it is the awareness of a semantic void – it’s a matter of language. As Tafuri maintains, ‘The necessary hypothesis is to construct with those decayed materials’. This signifies that this linguistic material no longer communicates anything; albeit untruthful, it is the only one available. Perhaps we should be consoled by the fact that, with a similar origin, Kollhoff’s work reached forms we recognize. Aside from objectively acceptable theoretical assumptions, this is what this book gives us.

Kollhoff gradually weakens all of the unease and unresolvable ambiguity of the Roman Drill Ground by rejoining typology and urban form, the building and its context, history and the present. Piranesi’s plate leads to the extreme consequences of the knowledge of a history that in itself no longer offers any value – it provides only a principle of authority to be challenged through subjective experience. Kollhoff’s creations try to solve this conflict by continually underscoring what history does not change: the permanent features and the sophisticated European urban culture that modern and contemporary architecture lost by staging a permanent crisis.

This modernity was dear to Bruno Zevi, and crises were valuable. But it seems alien to both Kollhoff and Ungers, his mentor, not to mention an entire school of architecture belonging to a clear, mainstream tradition. Of course, that foreignness is not always so evident. Some projects – such as the Luisenplatz apartment block, the projected ethnographic museum, the KNSM-Eiland district in Rotterdam, the bold Atlanpole Nantes competition entry – play another game. The Bonn Kunsthalle also differs, but the text does not: ‘The Kunsthalle is the expression of our time: consuming desire for security and technical potential’. Unfortunately, the consuming desire for security does mean big spending on the police.

Michele Calzavara Architect