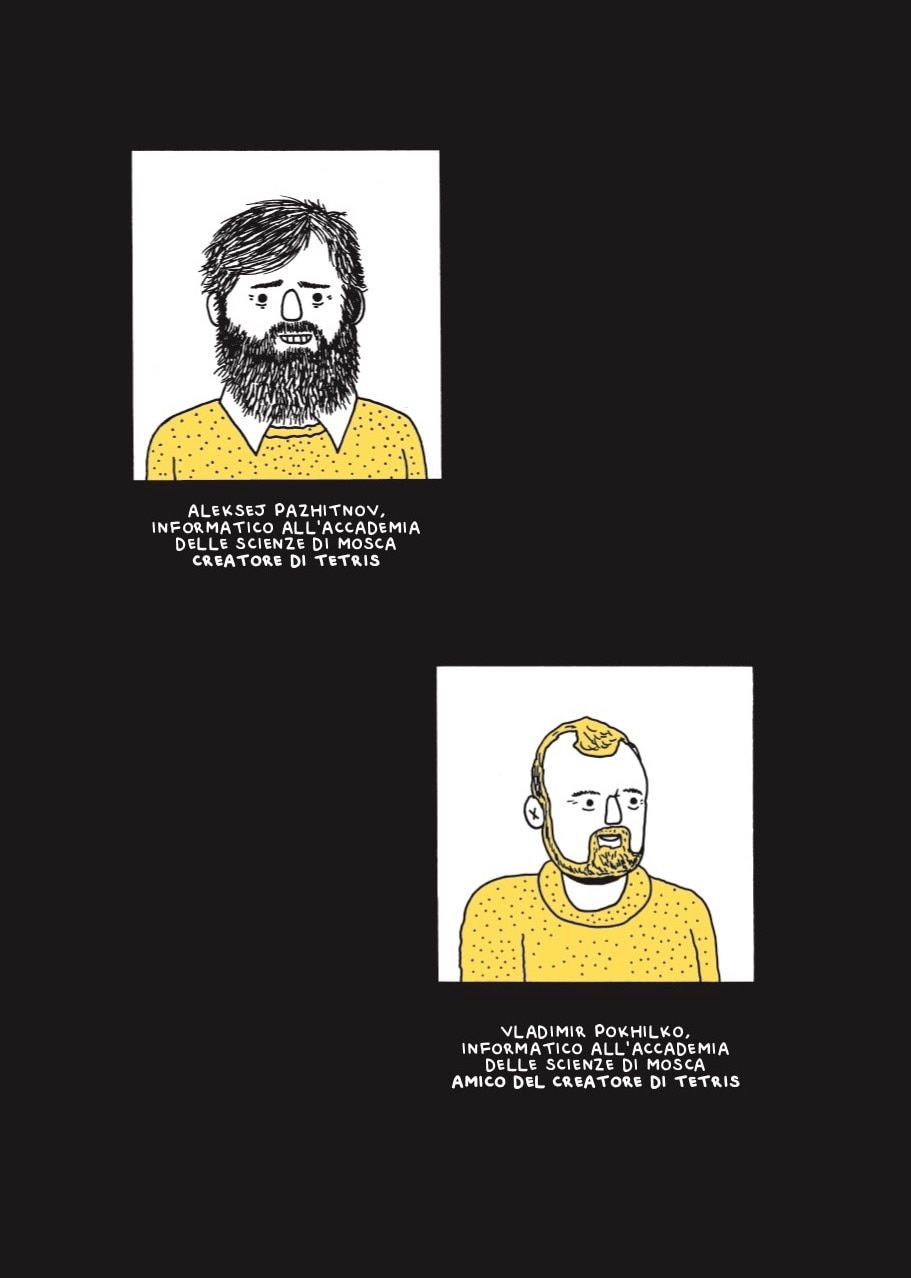

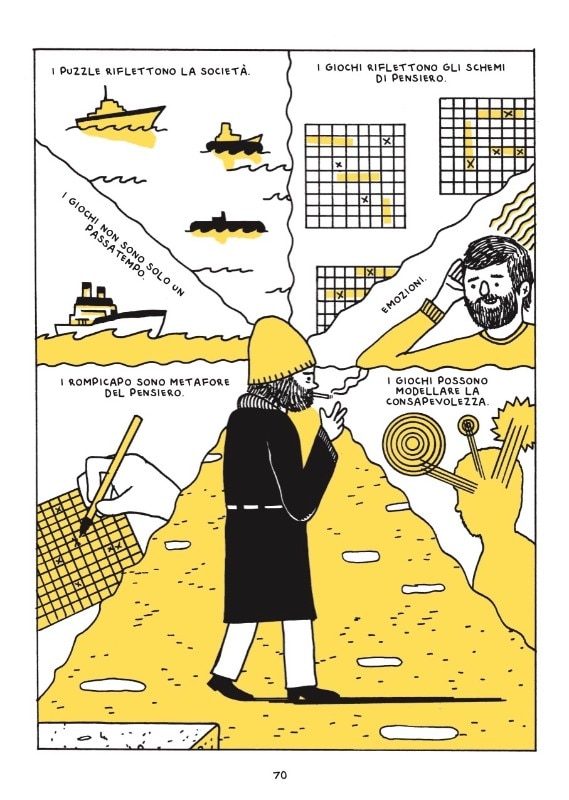

The history of architecture teaches us that placing one brick on top of the other is a way of building something by fitting together individual elements of various shapes and functions to create a larger, more complex figure with a much broader use than the individual elements. In the history of video games, this more or less modular principle has experienced one of the most significant contradictions of all times – Tetris, the game invented on June 6, 1984 by a young programmer working for the Soviet Academy of Sciences called Aleksej Pažitnov, in which the aim is to bring together as many elements as possible in order to... destroy them. Metaphorically speaking, in the real world, humans have aimed for the sky from the very first moment they had the ability to rise above the ground. In Tetris, on the contrary, one is forced to “aim for the sky”, but the winner is whoever manages to score the most points by avoiding making the pieces reach the top edge of the screen.

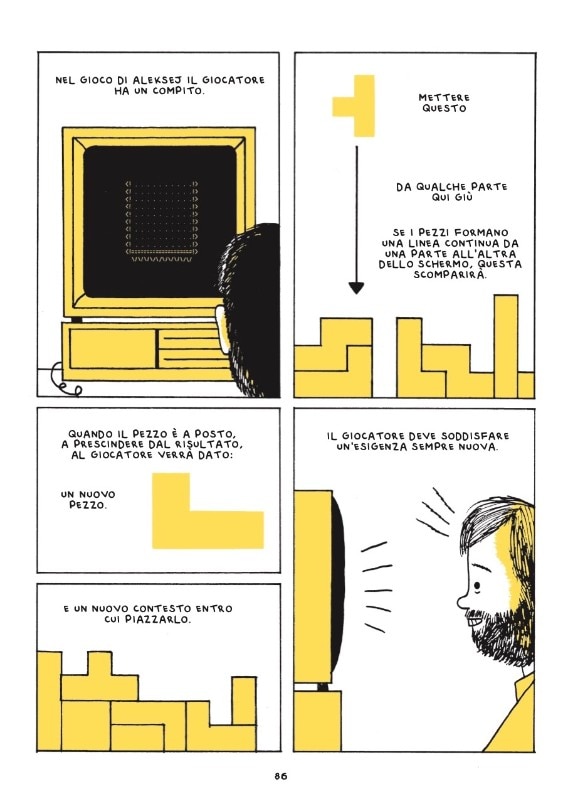

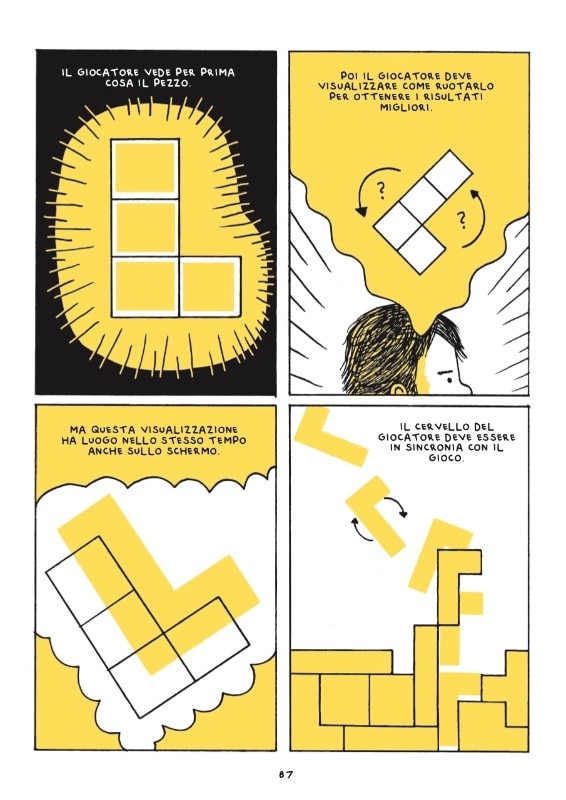

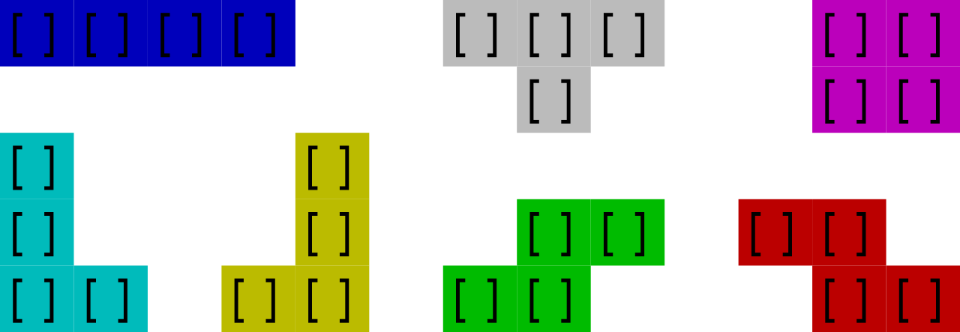

Tetris is a game where space and its exploitation are fundamental. You must optimise the arrangement of the individual tetriminos, each composed of four identical squares (the various now iconic shapes are always obtained with four repetitions of the same two-dimensional geometric figures). But how did we obtain such a visual synthesis, like the now iconic one of Tetris?

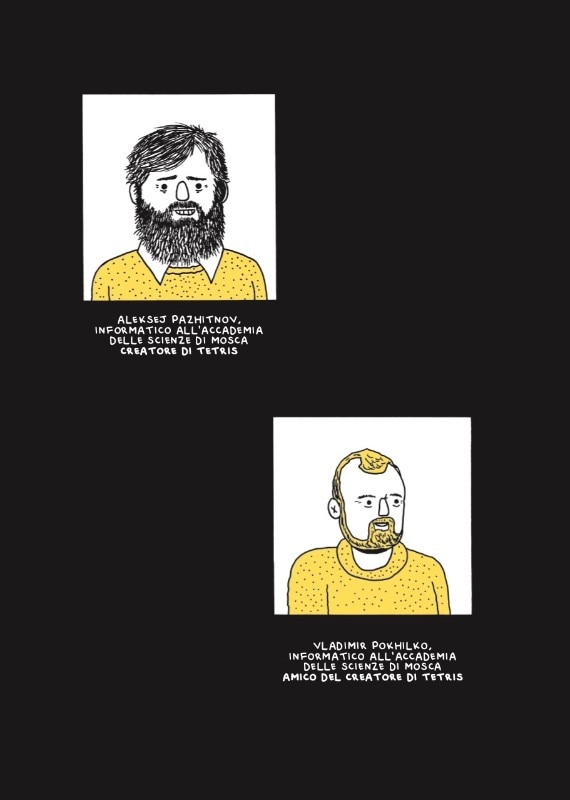

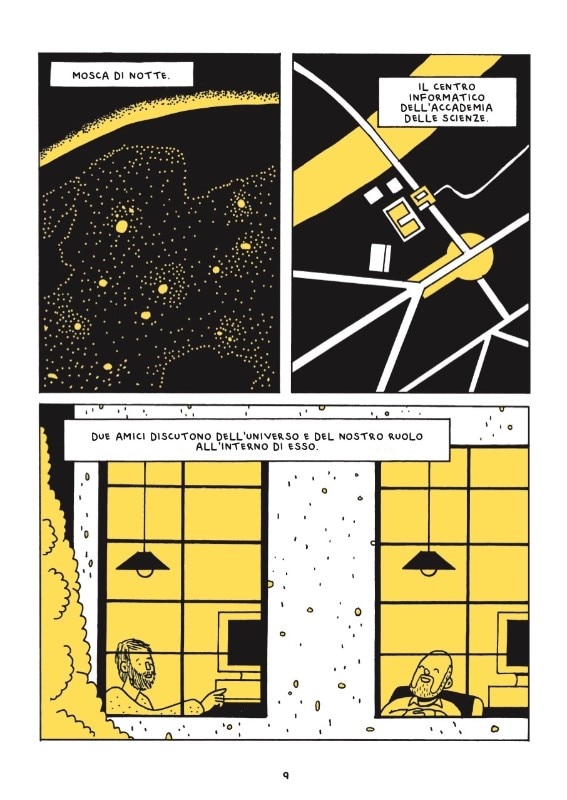

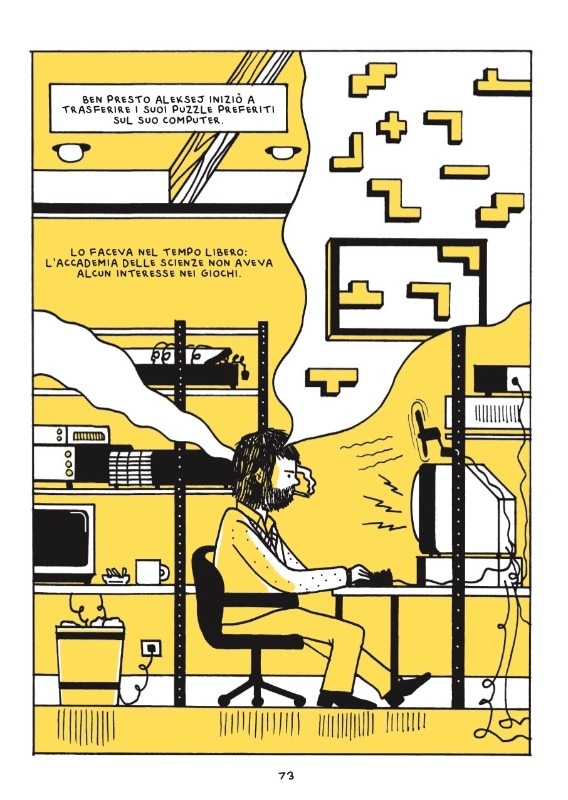

The birth of Tetris

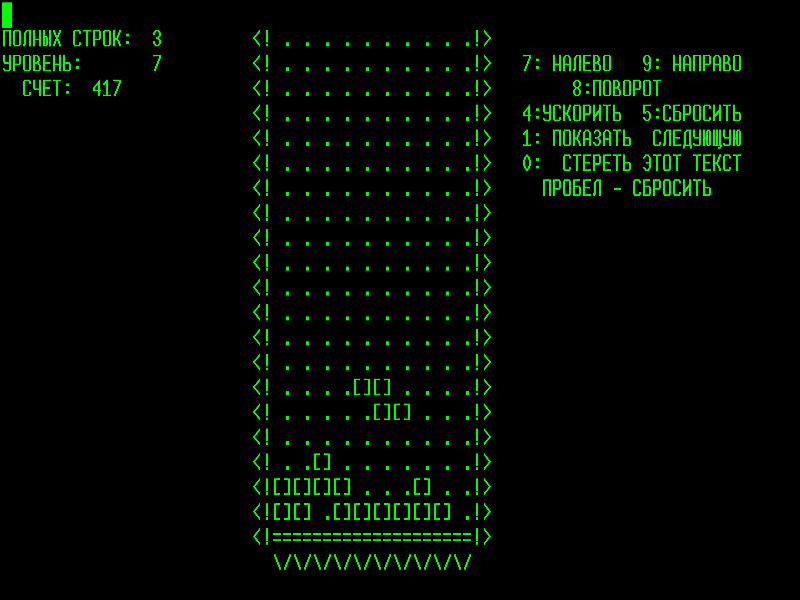

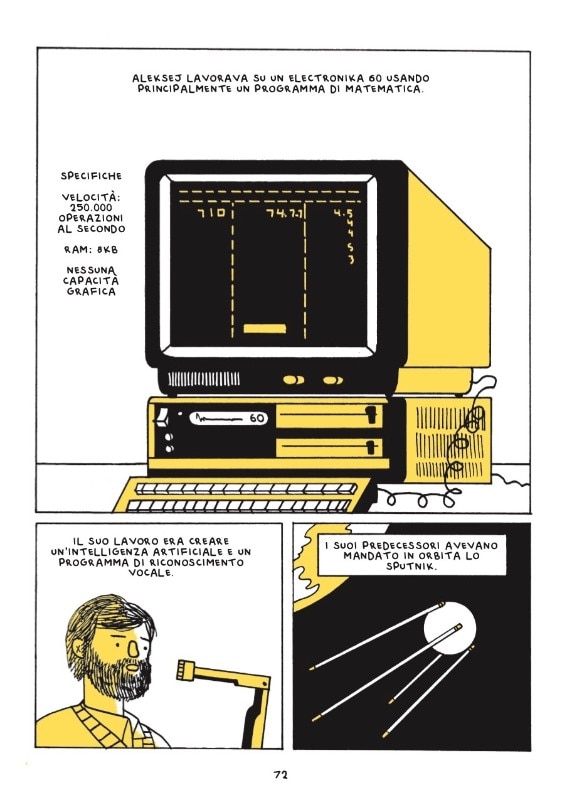

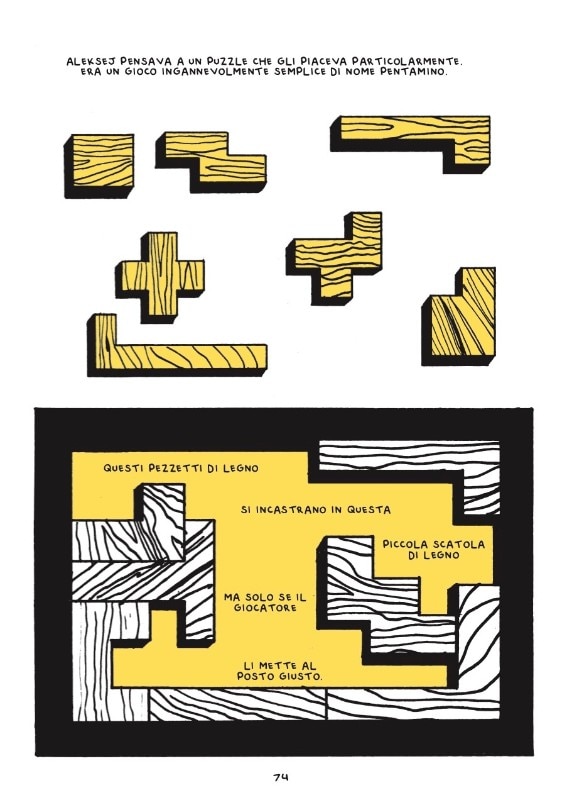

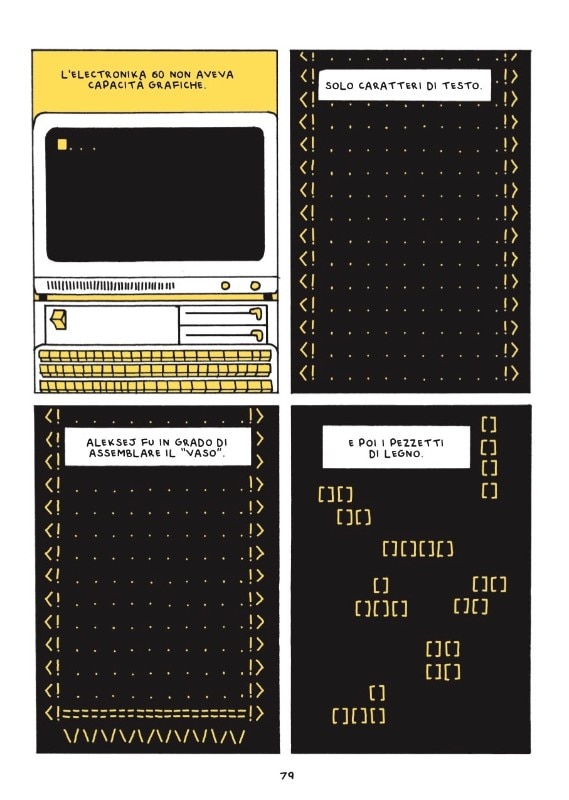

In the beginning, Tetris wasn’t meant to be about interlocking individual combinations of tetriminos. The first version was based on the use of pentominos (like tetriminos, only composed of five squares). What would have been the resulting visual harmony? Certainly very different. What is striking about the playfield today, for example, is precisely the harmony of the individual pieces and their combinations: with an additional module, there would certainly have been completely different combinations and shapes. The first version of the game created by Pažitnov used to run on an Electronika 60 machine, and its visual synthesis was even more abstract. At the time, the use of a graphical and attractive gaming interface was only a distant dream, and the visual synthesis of the blocks interlocking with each other was obtained by using two square brackets “[]”, which resembled a square shape. A bit like when in architecture, graphics and many other visual arts, the juxtaposition of two different elements reminds us of a third, different one.

Tetris and the Soviet Union

Tetris, however, is not only a beautiful story of creativity. It is a product that has given an important boost to the gaming industry, especially in terms of corporate interests and intellectual property. Pažitnov lived in the former USSR, a hortus conclususus hermetically closed to foreign influences. Yet, the revolutionary impact of Tetris was so important that it broke those borders and generated diplomatic conflicts with Japan and the United States.

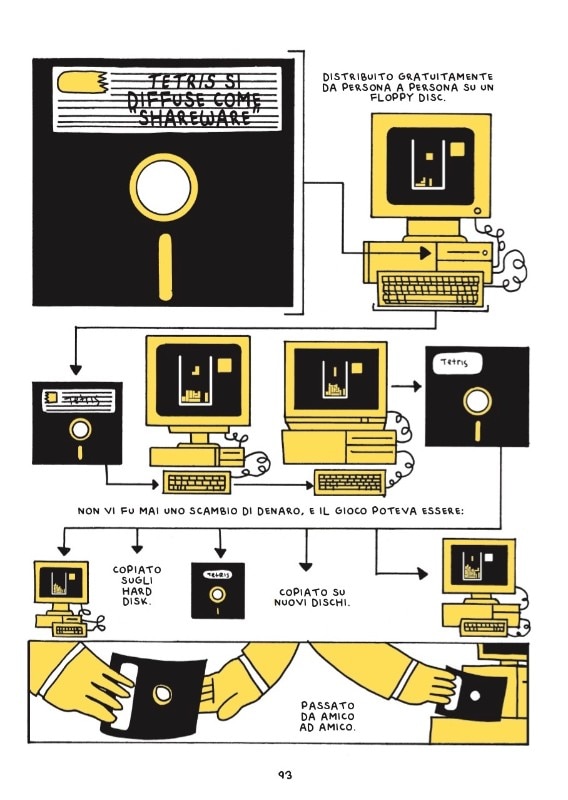

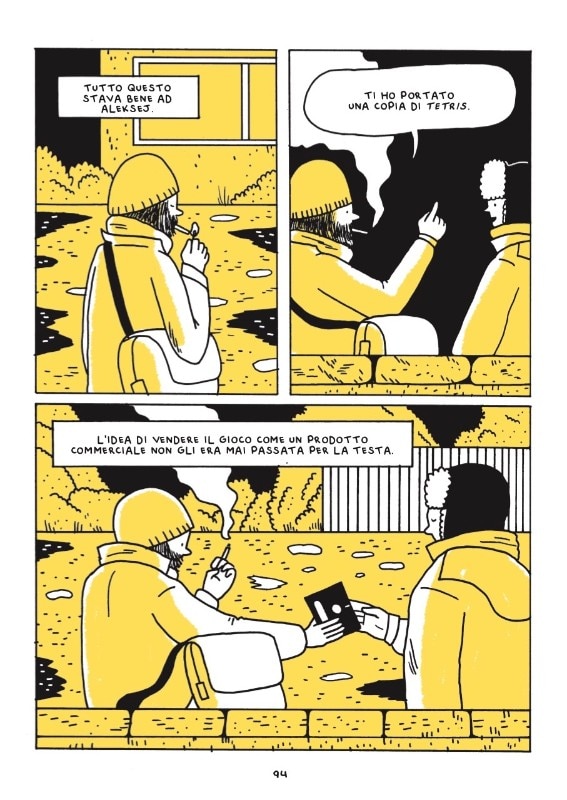

In all this process that has very little to do with creativity and much to do with bureaucracy, what is most striking is surely Pažitnov’s “choice” (if you can call it that) not to patent the game, anticipating in a more or less voluntary way of about a decade the culture of sharing ideas, which characterized the great Digital Revolution of the ‘90s. Why would he do this? There are some assumptions, many concerning the bureaucracy of the USSR and pressure from the government which was the only owner of the new “inventions” produced in the Soviet Union, and a pitiless censor that decided what could enter and leave (physically and culturally) the borders of the contry.

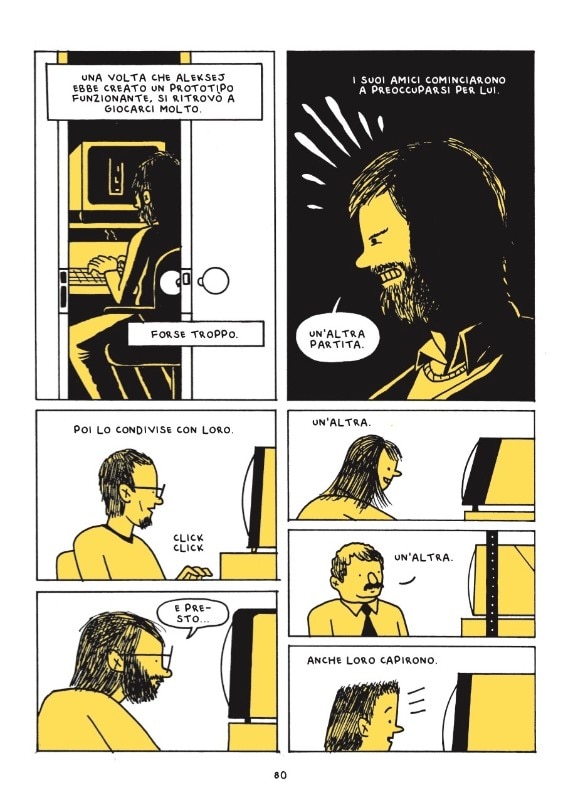

History of an idea

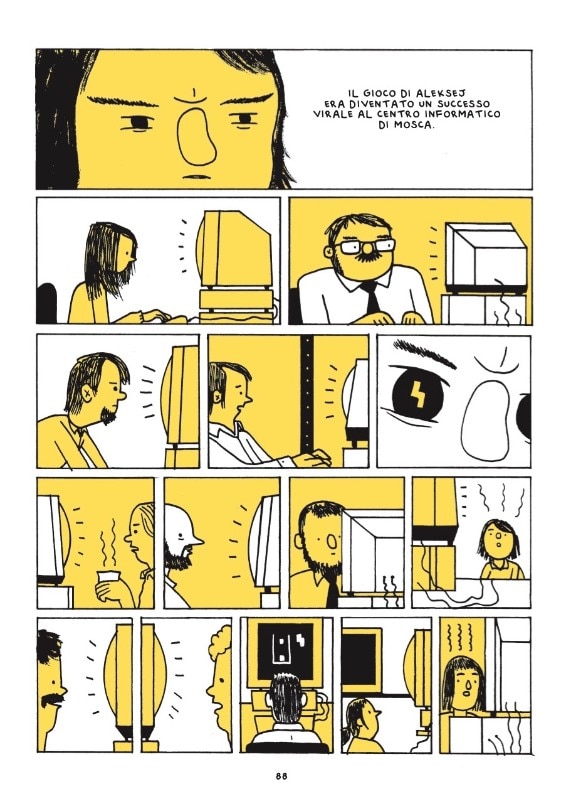

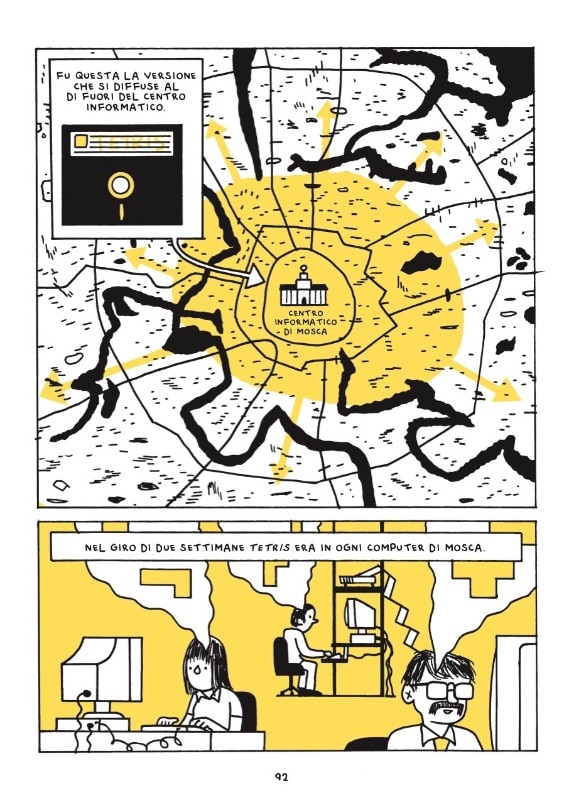

A great idea, but it can’t be kept under lock and key for long. Just as it hit Pažitnov’s colleagues, the Tetris craze became a widespread phenomenon in just a few years. Nikoli Belikov, which was the director of the state-owned with a monopoly on the import and export of computer hardware and software in the Soviet Union, was given the task to determine how the game should be distributed in other countries, and to answer the most difficult question that could be asked to the world since the Cold War: how to reconcile the interests of Western capitalism and Eastern communism? There are several books that have covered the whole evolution of its history in depth, including Dan Ackerman’s The Tetris Effect: The Game that Hypnotized the World (published by PublicAffairs) and the comic book Tetris: The Games People Play by Box Brown (published in Italy by Panini Comics).

But what are the most important aspects of this story? First of all, the way Pažitnov managed his “idea”: he literally defied death trying to reach an agreement with his own country, trying to impose the reasons of the individual and the author’s pride against the reasons of the state even just to have the possibility to continue to be a video game programmer… in the West – this was an unacceptable insult to the Soviet Government.

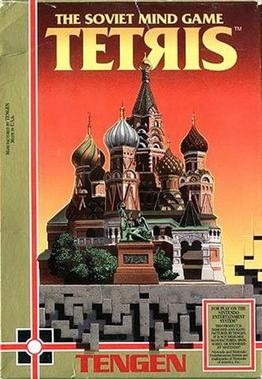

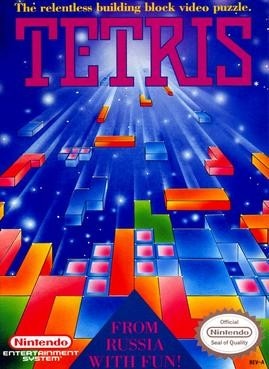

Then, we should talk about the distribution profile of the product. The video game market was very different from today’s, and the negotiations to bring a product from the programmer’s desk to the store shelves were also much smoother than you might imagine. Each market segment (European, Japanese and American, just to name a few examples) had different economic concessions, so that the resulting versions of Tetris were different from each other. To give a couple examples: Maxwell Corporation had reached an agreement to distribute the Game in the West, while Nintendo developed a version to play on the famous GameBoy. For purely contractual reasons, some versions were developed for personal computers only, excluding consoles. In short, in the years when the world fell in love with Tetris, in reality many versions of the same idea were marketed, also because of the slowness and complexity of the communications that took place at that time between one side of the globe and the other.

Towards the future

Tetris is heading towards its fortieth anniversary (in 2024), yet the freshness and simplicity behind its gameplay hasn’t aged a single day. Saint Basil’s Cathedral has turned the game’s packaging into an icon over the decades, and the distinctive music theme is still an unmistakable symbol, all over the world. It has been played on literally every technological device imaginable, in addition to the more traditional ones: calculators, watches, phones and many others. For every new technology that comes along, you can rest assured that there will be a version of the game on it.

%20-%20Imgur.gif.foto.rbig.png)