by Silvana Annicchiarico

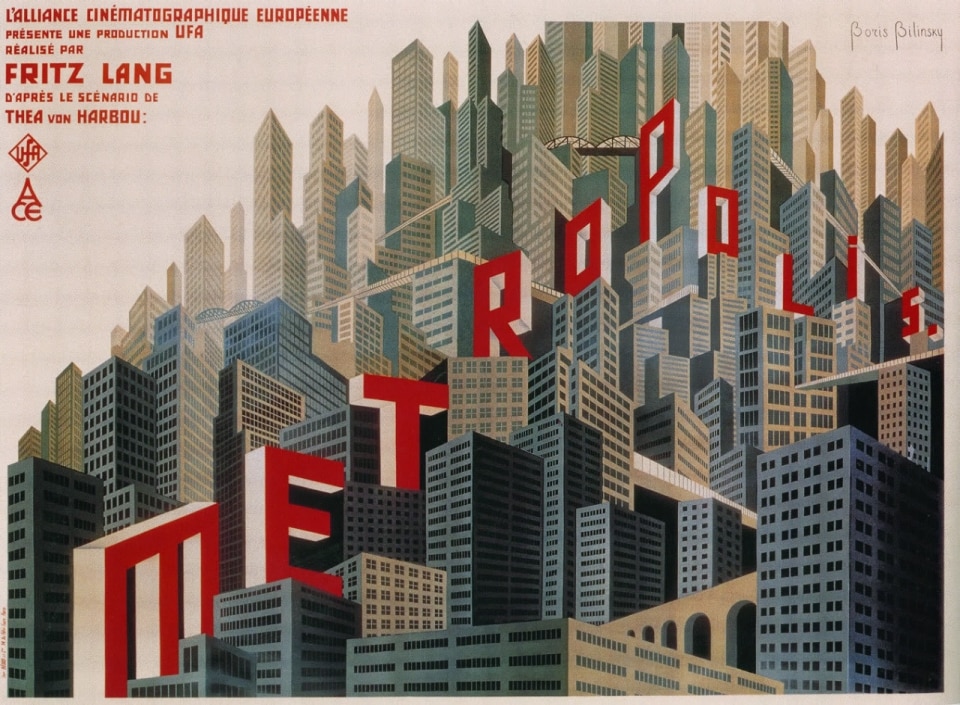

When Fritz Lang sets Metropolis in 2026, he is not imagining a distant future. He imagines a near tomorrow, plausible, imminent. A future which today, one hundred years after the film’s release (it premiered in 1927), eerily overlaps with our present.

The film opens with a declaration that sounds like a political axiom: “In 2026 the total oppression and manipulation of the masses is exercised by the unquestionable power of a minority.”

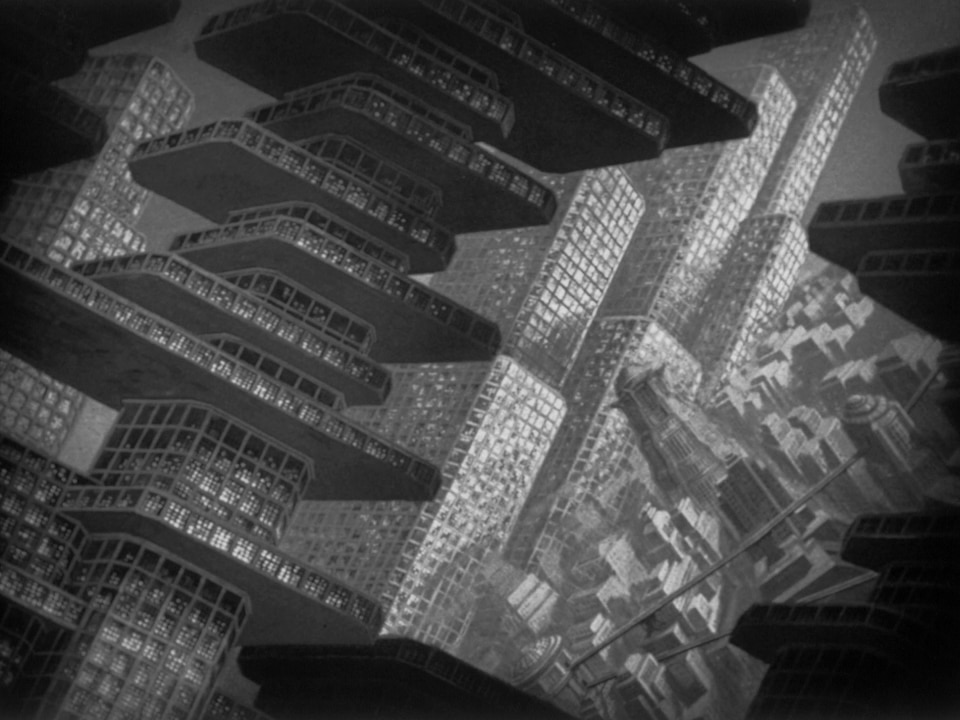

It is not a technological dystopia, but a designed social structure. Metropolis is a vertical, stratified, hierarchical city. Above, skyscrapers, leisure time, pleasure gardens; below, production; even further down, the bodies that feed the machine. Verticality is not an urban solution, but a form of power. Rising means deciding, descending means obeying.

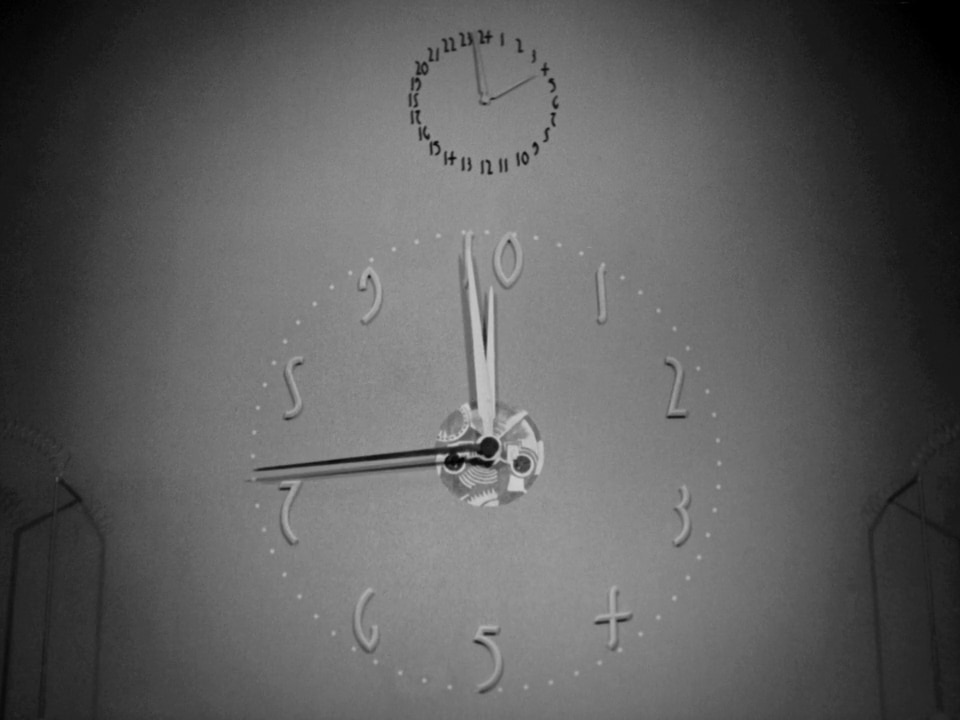

Time, in Metropolis, is not individual experience but a device of control. Clocks mark ten-hour shifts. There is no time for life, only time for work. Workers enter and leave the factory in perfectly aligned rows, heads bowed, synchronized movements. They are not people: they are flows.

Barometers, thermometers, pistons, gears, steam punctuate an uninterrupted rhythm. The underground city works without pause, invisible yet indispensable. It is an image we might now call a data center: a hidden infrastructure that sustains the entire system, but rarely enters the space of representation.

Metropolis does not show us the future. It shows what happens when the future is designed without heart.

The workers of Metropolis are not only exploited: they are rendered identical. Same submissive posture, same gestures, same rhythm. The individual body disappears in favor of standardized behavior. Lang anticipates with astonishing foresight a logic we now know well: the individual is no longer a person but a recurring model, a pattern. What matters is not exceptionality, but predictability.

When Freder, the son of the city’s master, descends underground for the first time, the machine becomes a mythological vision: Moloch, a monstrous mouth devouring masses of men. It is not an hallucination, but the revelation of the system. Technology, when it becomes an end in itself, demands sacrifice. Here Metropolis anticipates a question that forcefully returns today: who feeds the intelligence of the machines? Who pays the human cost of efficiency, automation, constant optimization?

The power that governs Metropolis does not need to show itself. Joh Fredersen observes from above, gathers information, controls flows. He never truly descends among the workers. The city is visible to power, but power is invisible to the city. This asymmetry of vision is one of the film’s most prophetic aspects: control does not require presence, but distance. It is already a primitive form of systemic surveillance, in which those who decide see everything and are never seen.

View gallery

View gallery

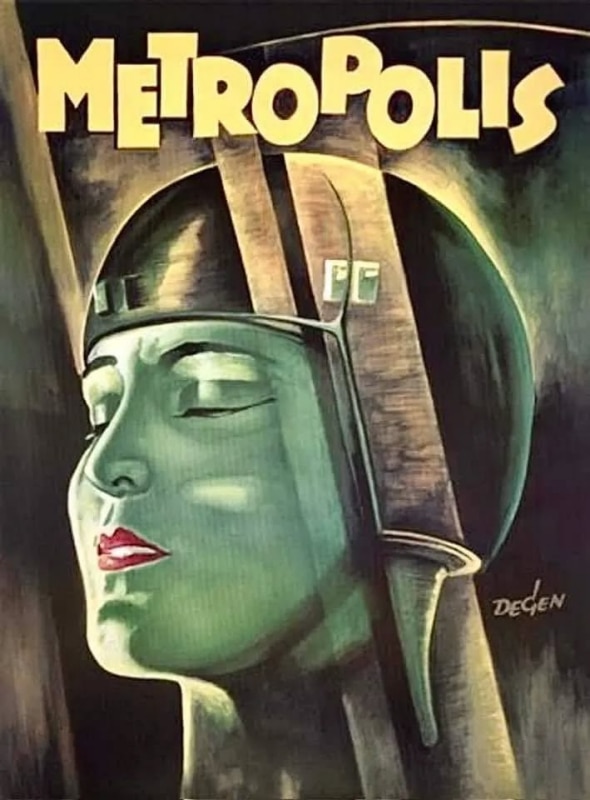

At the heart of the city survives an ancient, almost medieval house. Along with the subterranean catacombs, it is the only non-modern place in Metropolis. Here lives Rotwang, the inventor, a man obsessed with the memory of Hel. In attempting to recreate her, he constructs an automaton: a robot almost perfect, but without a soul. The city’s master wants it that way. Without a soul it is more useful, more controllable.

Here Lang makes a radical gesture: he introduces the first anthropomorphic avatar in cinema history. The robot has female features, seductive, persuasive. It does not work: it communicates. It does not produce: it orients. It is engineered to fascinate, to stir, to influence the masses. Its power is not coercive but charismatic. It seduces, excites, speaks to emotions. It is built to be believed, not to be true. In this sense it is the direct ancestor of digital avatars, virtual influencers, artificial intelligences designed to simulate empathy and steer behavior. Lang had already understood that the most effective domination is not the one that commands, but the one that captivates.

Robot-Maria incites revolt, but not liberation. It generates chaos, destruction, loss of control. The masses are no longer orderly lines: they become an indistinct crowd. The machines are destroyed, water floods the city, children risk dying. One worker alone remains lucid and delivers a disarming truth: “By destroying the machines, you destroy yourselves.”

Verticality is not an urban solution, but a form of power.

Lang rejects both the blind cult of technology and its demonization. The problem is not the machine, but automation without responsibility, intelligence without ethics.

Before Maria’s transformation into a robot, in the ancient cathedral, the theoretical core of the film resounds. Maria recounts the story of the Tower of Babel: “Those who designed did not know those who built, those who built did not know the purpose. The few who sang hymns became the curse of the many.” And comes the emblematic sentence: “Between the brain that plans and the hands that build, the heart must be the mediator.”

Here Metropolis speaks directly to our present. Between those who write the code and those who suffer its effects; between those who train the algorithm and those who are classified, profiled, excluded. Without human mediation, without responsibility, artificial intelligence becomes nothing more than a machine of power.

Today cities are no longer merely vertical: they are invisible infrastructures of data. Work is hidden, fragmented, displaced. Decisions are taken by opaque systems. Avatars speak with human voices, but answer to non-human logic. The robot of Metropolis is not a past mistake: it is a warning.

Metropolis does not show us the future. It shows what happens when the future is designed without heart. In 2026, exactly one hundred years later, the question remains unanswered: who governs the intelligence that governs us?

All images: Fritz Lang, Metropolis, 1927