by Ramona Ponzini

The set design of the Nostromo for the original Alien by Ridley Scott marked a turning point in science-fiction design. Chris Foss and Ron Cobb, two highly influential sci-fi illustrators and concept designers, gave shape to the visual language of the genre by conceiving the Nostromo as an orbital refinery. The logic was a direct translation of terrestrial infrastructures: power plants, loading platforms, industrial ventilation systems. Pipes, valves, grilles, and cables were all exposed, with no attempt at formal cleanliness. The ship did not simulate technological transparency, but rather the heaviness of the productive machine.

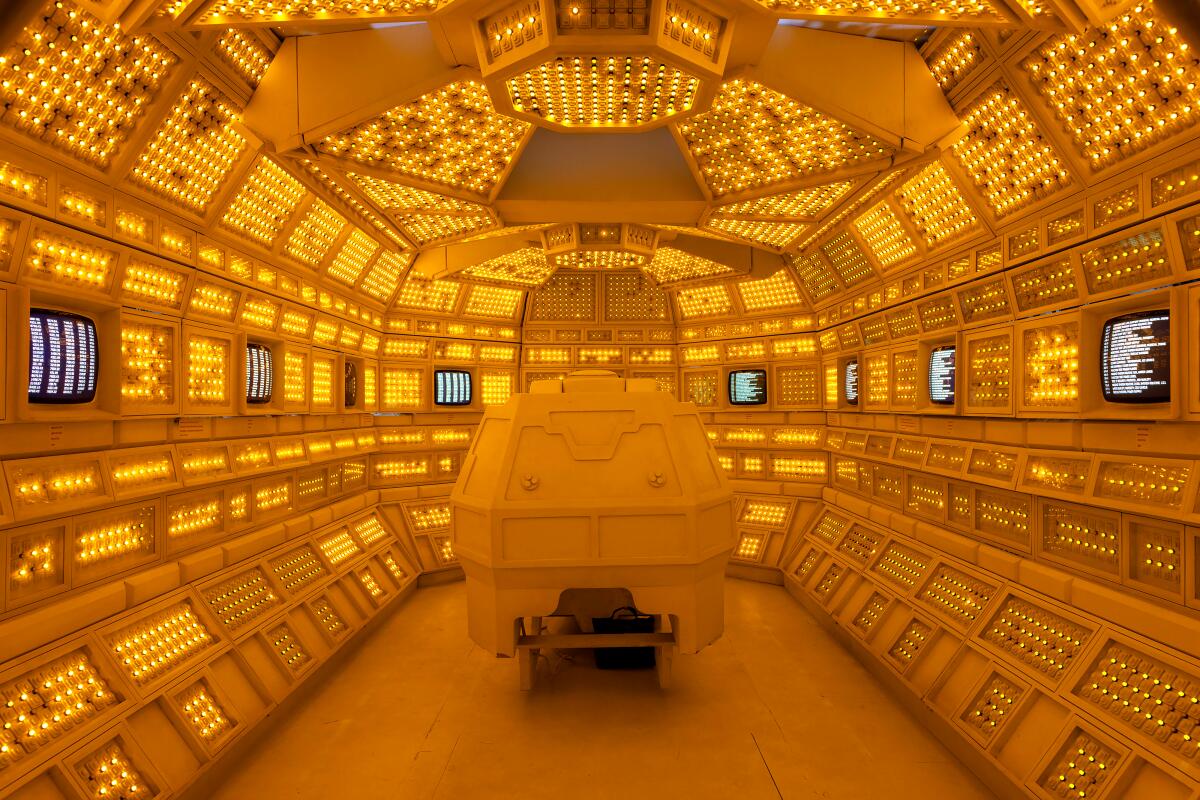

This approach sharply contrasted with the sleek aesthetics of films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Where Kubrick proposed pristine interiors, smooth surfaces, and environments conceived as ideal architecture, Scott showed saturated, opaque spaces dominated by the visual noise of technology. To the rational purity of Kubrickian modernism, Scott opposed the raw materiality of industrial infrastructure. The Nostromo’s interiors were structured as an assemblage of functional modules, lacking any centralized aesthetic order. Corridors resembled service ducts, control rooms overflowed with analog instruments and redundant panels. Man was not at the center of the design, but inserted into a machine that engulfed him—an environment where functionality prevailed over form, and form itself emerged from technical stratification.

Hans Ruedi Giger, the Swiss artist known for his “biomechanical” imagery, joined Scott after the director saw his drawings for the book Necronomicon (1977). His aesthetics—hybrid bodies, organic forms grafted onto mechanical structures, and a disturbing eroticism—defined the look of the “alien,” i.e., the xenomorph and its original environments.

The introduction of Giger’s creature created a radical rupture. The xenomorph carried a morphological language foreign to the modular aesthetics of the ship. Its glossy skin, skeletal structure, and flexible appendages contradicted the metallic linearity of the environment. The Nostromo’s architecture could not contain the monster; instead, it revealed its otherness. Corridors became traps, rectilinear geometries bent to the unpredictability of the organic body.

One of the film’s revolutionary aspects lies precisely in this dichotomy, in the clash between two visual orders capable of redefining the horizon of science fiction.

Aliens (James Cameron, 1986): LV-426 and the colony as frontier

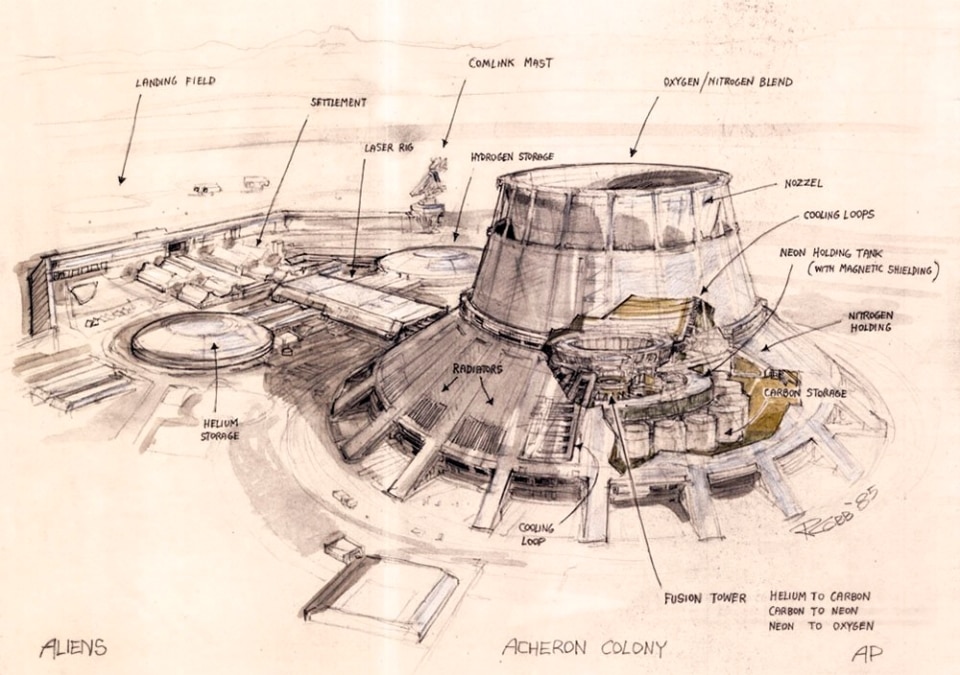

Cameron revisited LV-426, the rocky moon only glimpsed in the first film, transforming it from enigma into architectural stage. Where the first film left the planet as a liminal space defined by storms and rocky horizons, Aliens turned it into the site of systematic intervention: terraforming and the construction of a mining colony. Designed by Peter Lamont, the colony’s housing and industrial complexes reflected modular and prefabricated late 20th-century industrial architecture. Geometric blocks, functional corridors, internal and external piping systems: every element suggested a temporary, replaceable settlement.

Hadley’s Hope was conceived as a projection of Weyland-Yutani’s extractive logic: not built for permanence, but as a sacrificial outpost, meant to be replicated and discarded. The planet’s landscape was never neutral—its rocky expanses and electrical storms were absorbed into an industrial grid that imposed itself without dialogue. The aesthetic tension stemmed from this dissonance between a radically hostile geology and the artificiality of human structures.

Architecturally, the xenomorph’s proliferation found its battleground: the modular corridors of the colony became ambush spaces, the industrial grid a net captured and warped by an organic order. Cameron emphasized the geometric conflict: rational linearity versus the rhizomatic spread of alien nests, with resinous surfaces overtaking and deforming structures. LV-426 thus embodied the fragility of the frontier: an industrial expansionist rhetoric collapsing before an organism that rewrote its architecture.

Alien³ (David Fincher, 1992) and Alien vs. Predator (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2004): prison and pyramid

The penal colony Fiorina 161 in Alien³ fully embraced the characteristics of control architecture. Designed by Norman Reynolds (Oscar-winning production designer of Star Wars and Indiana Jones), it evoked both abandoned industrial complexes and fortified monasteries. Narrow corridors, wrought-iron staircases, armored doors, and bare common spaces produced a carceral geometry without openings to the outside. Punitive and monastic, it became both forced-labor site and place of spiritual confinement.

This setting radically reframed the creature. Where the first Alien intruded into an industrial machine, here it prowled a system already built as a trap. The prison’s galleries and ducts became hunting grounds, overturning the panopticon logic: no longer did the institution control the prisoner, but the organism subverted the architectural apparatus. The prison became a predatory labyrinth, its disciplinary rationality imploding under the pressure of organic presence.

In contrast, the Antarctic pyramid of Alien vs. Predator abandoned industrial logic for monumental archaeology. Mesoamerican and Egyptian elements fused into a symbolic and ritualistic architecture. Corridors and chambers followed a sacred logic, with shifting walls, reconfigurable spaces, and entire structures operating as narrative machines.

Here, the xenomorph was no longer radical otherness but integrated into ritual cycles. The pyramid was not invaded but designed to host the monster: architecture itself inscribed the creature within an initiatory code. While Alien³ revealed the fragility of disciplinary systems, AVP offered the opposite model—an environment predesigned for the alien, celebrating rather than resisting it.

Alien: Resurrection (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997) and Alien: Romulus (Fede Álvarez, 2024): the ship as laboratory

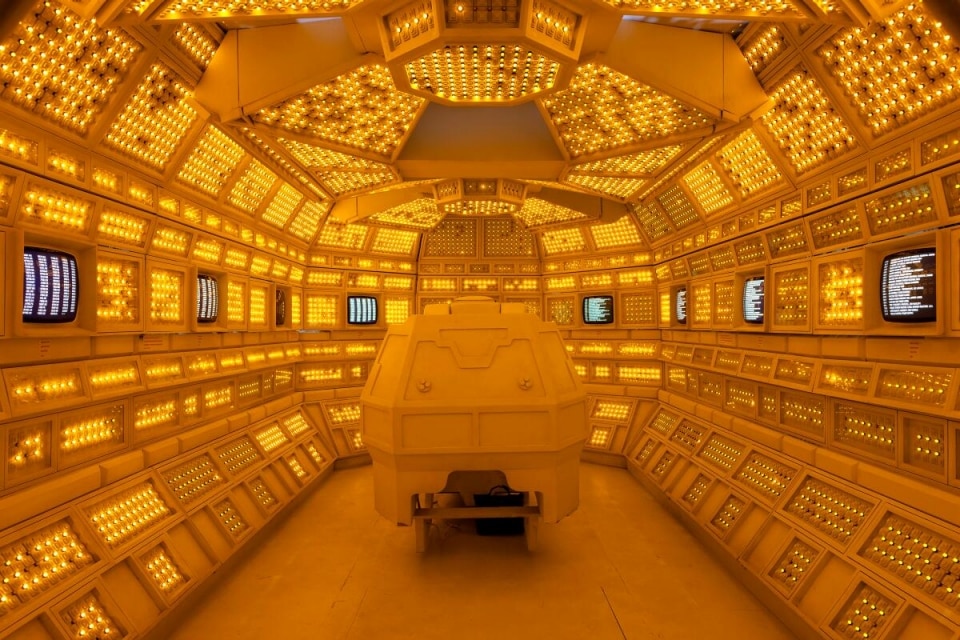

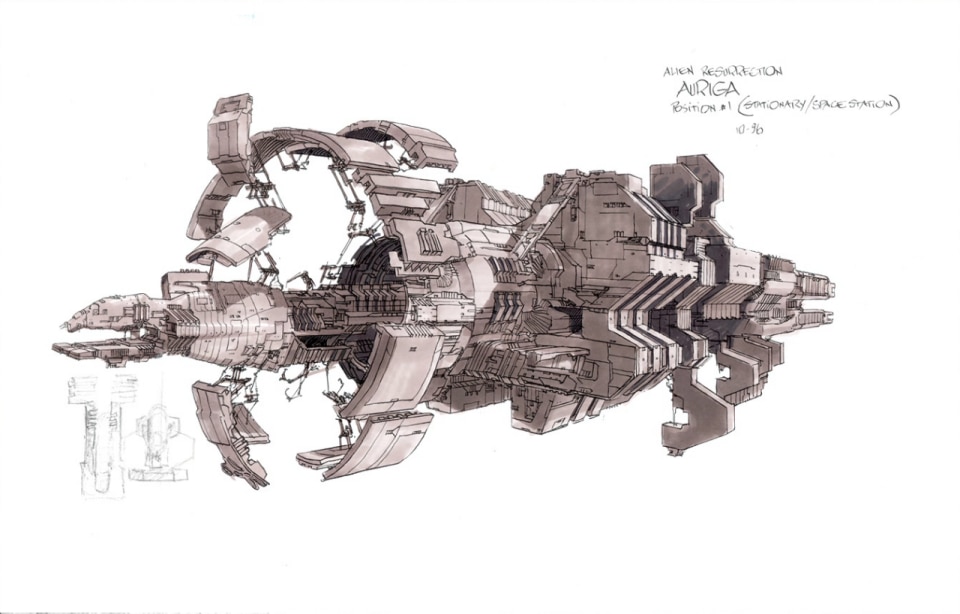

In Resurrection, Nigel Phelps’ set design abandoned prior aesthetics for a hybrid language: rational modularity of research facilities combined with Jeunet’s stylized vision. Every space seemed designed to contain, observe, and exploit.

The Auriga’s architecture embodied compartmentalization. Labs, containment cells, and technical spaces were isolated, connected only by passages reinforcing control logic. Manipulation was central: the ship analyzed, dissected, cloned. Science merged with militarism, reflected in geometric rigor bent toward coercion. In this context, both Ripley and the xenomorph were raw material, already inscribed into architecture’s functioning.

Alien: Romulus shifted to a space station with dual structure.

The architecture of the Renaissance, the space station that serves as the setting for Alien: Romulus, is conceived as a device of cinematic memory: divided into two distinct modules, Remus and Romulus reflect two aesthetic and technological eras of the saga. The Remus module recovers the industrial and functional materiality of Alien (1979); the Romulus module, where the action is focused, draws inspiration from the visual universe of Aliens (1986). This duality, far from being a mere stylistic exercise, delivers to the viewer a deliberate act of production design: the station does not unify the visual languages but sets them in contrast, transforming architecture into a meta-cinematic commentary. The design thus becomes a bridge between two visual traditions, inscribing the story in a dimension suspended between memory and renewal. The final effect is a space in which the viewer recognizes the franchise’s genealogy through the very shapes of its environments.

In both films, the spaceship and the space station no longer function as productive infrastructure or colonial outposts, but as extended laboratories. The alien organism does not threaten from the outside, but is born from within, produced and contained by the very architectural machine that is supposed to hold it.

Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012) and Alien: Covenant (Ridley Scott, 2017): planets as cosmic architecture

With Prometheus, Scott abandoned industrial imagery for monumental archaeology. LV-223’s basaltic landscapes and stormy skies concealed the Engineers’ mountain-ship: a cyclopean structure with curved geometries and superhuman proportions. Smooth surfaces lacked technological readability, suggesting a science inscribed in symbolism rather than technique.

The planet became a tension field between hostile nature and cosmic architecture. The underground lab was not industrial but sepulchral, a tomb-like chamber of conservation and cult. Here, the xenomorph’s genealogy emerged not as intrusion but as coherent product of a biological-constructive logic.

Covenant shifted to the Engineers’ ruined homeworld: monumental cities reduced to devastation. Squares, temples, and urban layouts echoed fossilized classical metropolises, centripetal and theatrical. David the android transformed these ruins into an open-air laboratory, merging archaeology and biotechnology.

The contrast lay in transition: intact monumentalization in Prometheus versus ruinous experimentation in Covenant. In both, planets operated as totalizing spaces, incorporating and transforming the organic within designs beyond the human.

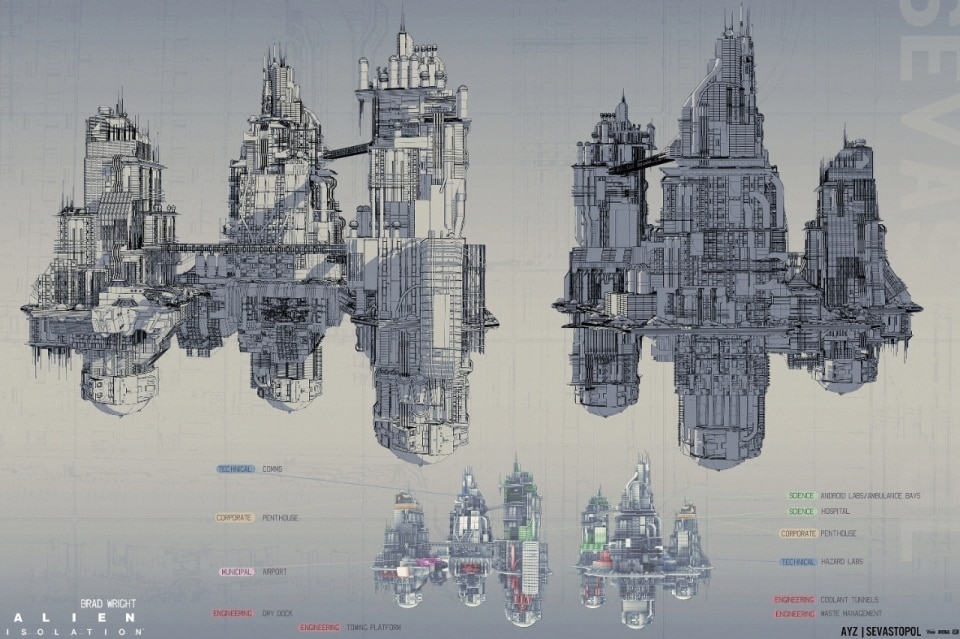

Alien: Isolation (Creative Assembly, 2014): the Sevastopol Station

The Sevastopol Station represents a unique case in the franchise: an architecture that does not belong to cinema but to video games, designed to be traversed and inhabited in first person. The design reprises the visual codes of 1979, but with a philological reconstruction translating the analog aesthetic into immersive experience. Narrow corridors, bulky panels, flickering lights, and obsolete mechanical systems compose an environment that preserves the industrial materiality of the Nostromo, amplifying its claustrophobic dimension. Unlike cinematic ships, the Sevastopol is articulated as a ludic system. Its architecture is conceived as a gameplay device: hiding spaces, alternative paths, nodes of visual and sound tension. Every corridor becomes a scenario of tactical choice, every environment a potential refuge or trap. Architecture does not only tell a story, but directly structures the player’s experience, transforming space into mechanics.

The station also appears as a testimony to peripheral capitalism. This is reflected in the design: worn surfaces, malfunctioning systems, partially abandoned environments. The architectural landscape thus becomes social commentary, conveying the sense of a universe in the grip of the alien threat.

Maginot, Prodigy City, and Neverland: the triple scenario of Alien: Earth

In Alien: Earth, the recent Disney+ series, Earth in 2120 is controlled by five mega-corporations: Prodigy, Weyland-Yutani, Lynch, Dynamic, and Threshold. National governments no longer exist: cities and infrastructures are the direct property of these economic entities, which impose their spatial and social logics on every aspect of human life.

USCSS Maginot, Weyland-Yutani’s spaceship, precisely reprises the design of the 1979 Nostromo. Production designer Andy Nicholson used the original blueprints to recreate spaces such as the bridge, the mess hall, and the MUTHUR room, preserving visual and sensory continuity with Scott’s film. The ship maintains its functionality as an industrial environment, but is translated into a contemporary narrative requirement, becoming an orbital laboratory in which the organic and the technological interact in a calibrated way.

Prodigy City, the global capital under the control of Prodigy Corp, owned by Boy Kavalier, mixes brutalism with Thai influences. The architecture combines monolithic masses, raw concrete surfaces, and functional geometries with exotic aesthetic details, generating an urban landscape that communicates power and control. Here cities configure themselves as total corporate apparatuses, where the boundary between public and private space is fully absorbed into corporate logic

View gallery

View gallery

Neverland (also the work of Kavalier), the island laboratory, far from the rest of the world, is conceived to contain experiments on humans and robots (the so-called hybrids), allowing biotechnological manipulation under controlled conditions. Buildings are functional, organized for monitoring and laboratory management, the interiors of residential spaces recall Scandinavian design, while the surrounding landscape is wild, rich with humid and lush tropical vegetation.

In the juxtaposition of the three main environments of Alien: Earth—Maginot, Prodigy City, and, above all, Neverland—the xenomorph assumes a profoundly different role compared to the tradition of the franchise. No longer only intruder or threat, the creature becomes an element of dialogue with the environment and with the more evolved beings generated in the laboratories. Precisely on this particular Island of Lost Children, the contamination between nature and architecture allows the xenomorph to enter into relation with humans, rewriting its traditional otherness and transforming it into the protagonist of a system of interactions never explored before.