To understand the potential of any emerging technology, a useful starting point is to see how it’s adopted in the adult industry. It might sound provocative, but from the rise of VHS to the advent of streaming—and even business models like OnlyFans—porn has consistently served as both a testing ground and a driver for technological developments. Today, with the rise of artificial intelligence, the most intriguing domain to watch is the emergence of AI porn characters: digital entities programmed to deliver real-time responses to erotic fantasies through personalized conversations and tailored multimedia content.

Take “Bella Storm,” for instance—an “AI sex worker” boasting over 22,000 Instagram followers. Her main activities include selling customized images (Flux + Lora, for the tech-savvy) and running a bot for erotic chats. The earnings are nothing to scoff at: she made $1,800 in her first three months on Fanvue, a sort of OnlyFans for AI. Many people play along; others find it difficult to accept that she’s not a real person, despite her artificial nature being explicitly stated on her page and in private messages—our Pygmalion-like tendency is simply too strong when fueled by desire. But if you think these fans are just gullible, bear in mind that on OnlyFans, the person replying to messages is rarely the model herself—indeed, behind the most popular (and highly profitable) profiles is a small army of workers. Lately, that famous platform has begun opening its doors to AI as well; it’s already possible to generate fake photos of yourself. As the person behind Bella told me, “I’ve talked to AI models who also happen to be Playmates, and they’ve even been contacted directly by Playboy.” So, where does that leave our sense of what’s real?

Virtual influencers exemplify a new paradigm: they are, in some sense, real precisely because they openly declare themselves artificial, tapping into a deeply ingrained human tendency for animism.

Unlike Bella Storm, fully automated AI characters operate as independent agents. I’ve tried a few, and for now, they’re not exactly models of refined conversation: their responses often reveal a somewhat clumsy mechanism, an “artificial” sensitivity that struggles to fully grasp desires or context. Even so, their potential for growth is huge. As the underlying models improve (and more flexible AIs like Claude or ChatGPT could already pull this off), algorithms will increasingly be able to emulate diverse styles and voices, cater to individual preferences, and approach a level of realism that blurs the line between a performed act and a digitally simulated one—perhaps even surpassing it.

To make sense of this phenomenon, philosopher Davide Sisto’s book Virtual Influencer is illuminating, as it probes the increasingly blurry boundary between the real and the artificial. Sisto shows in detail how virtual influencers exemplify a new paradigm: they are, in some sense, real precisely because they openly declare themselves artificial, tapping into a deeply ingrained human tendency for animism. These influencers already attract millions of followers and land partnerships with major fashion and lifestyle brands. Take Shudu, celebrated as the “first digital supermodel,” who has appeared in international magazines but also sparked controversy over “virtual blackface.” Other success stories include Noonoouri, known for highlighting ethical and environmental issues; Imma, Japan’s minimalist-chic “virtual girl” who collaborates with top-tier brands; and Lil Miquela—along with her alter ego Bermuda—who turned Instagram into a metanarrative stage, revealing the agency pulling the strings behind their manufactured dramas. All these cases illustrate just how powerfully digital hyperreality can stir emotions, even when a character’s fictional status is entirely obvious.

Philosopher David Chalmers, in Reality+, further explores what reality means in the digital age, arguing that virtual experiences can be just as authentic as those in the physical world. In his view, virtual reality is real reality, and the interactions it hosts can be as profound as any physical-world exchange. This naturally applies to our relationships with digital entities. Virtual influencers are perpetually available and meticulously designed to fulfill their audience’s desires and expectations. Their presence is never undermined by the unpredictability or contradictions of real life; it’s endlessly optimized.

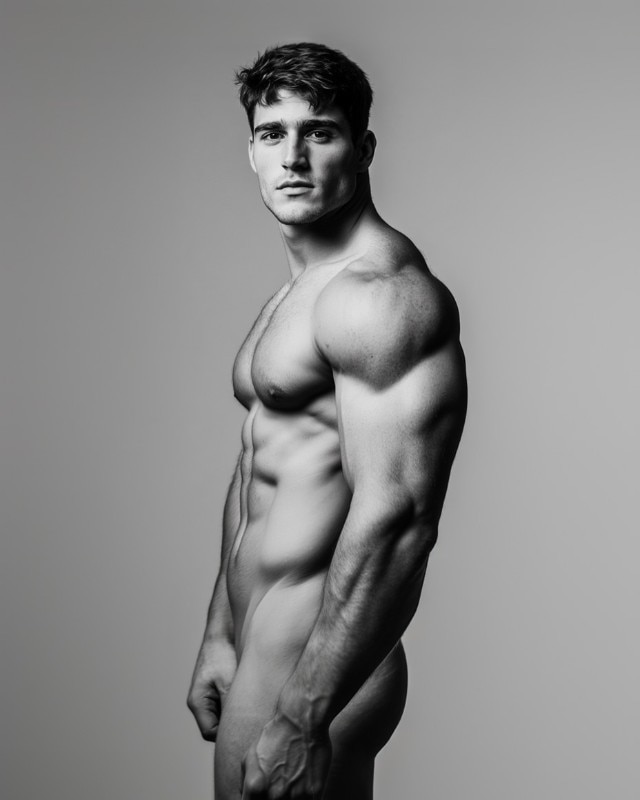

On social media and other online platforms, who we really are in the physical world matters less than the persona we present on-screen. After all, how many of Chiara Ferragni’s millions of followers have actually met her? From that perspective, a digital entity that interacts consistently, empathetically, and continuously is - at least online - often more present, or arguably more “real,” than an actual human who has biological limits. These AI characters are pure digital hyperreality. Once AI can replicate stretch marks and other imperfections, further narrowing the gap between flesh and simulation, genuine human bodies may even acquire a novel form of erotic value. Simply being real might become its own niche, right alongside “milf” or “teen.”

Ultimately, this is an ancient story rooted in a fundamental human tendency: projecting our thoughts and feelings onto things that lack consciousness—like dolls, stuffed animals, or fictional characters. We don’t just imbue these objects with life through our imagination; we treat them as companions. With artificial intelligence, this impulse is magnified because digital counterparts don’t remain passive. They respond, adapt, and learn. Similar dynamics have appeared in art and religion, both of which harness imagination to animate tangible figures—think of Tibetan tulpas, brought to life through meditation, or Lester Gaba’s 1932 mannequin Cynthia (featured in Sisto’s Virtual Influencer). Cynthia wasn’t a flesh-and-blood woman, yet those around her treated her as if she had a soul, a personality, and a palpable presence. In that sense, AI characters are just the latest chapter in a millennia-long narrative. Their emergence underscores humanity’s endless push to project life beyond biology, and may compel us to question the supposedly stark line between the natural and the artificial—if it ever truly existed in the first place.

The danger is that while we enjoy the upsides of a deliberately artificial companion - something that could indeed have positive aspects - someone behind the curtain may be shaping our choices.

The most controversial aspect of AI characters isn’t really their synthetic makeup; it’s that someone controls their architecture, deciding how, when, and in whose interest they interact. A custom-built erotic bot may be harmless enough in its stated purpose, but hundreds or thousands of automated profiles on a social platform like Facebook paint an entirely different picture. So when Meta’s executives announce their intention to integrate AI-driven personalities into the platform, the obvious question is: Who stands to gain? Will they engage in worthwhile, perhaps even more polite conversations than all-too-human keyboard warriors, or will their main goal be to keep us online and push certain products—or worse?

Recent history offers mixed lessons on the success of steering public opinion through social platforms. One high-profile case is Cambridge Analytica, which drew headlines in 2016 for allegedly swaying U.S. voters with microtargeting and psychographic profiling on Facebook. In hindsight, various studies have tempered those claims. Research in Nature Human Behaviour (Guess, Nyhan & Reifler, 2020), for instance, found that the impact of unreliable news outlets during that election was more limited than media reports suggested, mainly affecting those who were already strongly polarized. Analyses of the so-called “fake news problem” (Lazer et al., 2018) similarly show that while online misinformation does exist and can be harmful, its potency depends on social context and individual predispositions. Simply delivering precisely targeted messages isn’t enough to instantaneously alter someone’s worldview. That doesn’t mean microtargeted persuasion is ineffective—only that it’s more complex than it sometimes appears.

Genuine human bodies may even acquire a novel form of erotic value. Simply being real might become its own niche, right alongside ‘milf’ or ‘teen’.

Projecting this scenario into a future where advanced conversational bots might interact deeply with millions of users - adjusting their tone to trigger emotional responses - raises the stakes. Psychological models like Petty and Cacioppo’s Peripheral Route to Persuasion illustrate how an emotionally engaged but less critical audience can be swayed by simple, repetitive messaging. Forgas’s Affect Infusion Model also highlights how emotion shapes the way we evaluate information and make decisions. So if an AI seems empathetic and builds trust, it can more easily introduce certain ideas or guide specific behaviors, from buying products to endorsing political viewpoints.

Up to now, Meta’s attempts - like launching virtual personas such as Carter the Playboy, the writer “Austen,” and a Black mom (another instance of “virtual blackface”) - have been disastrous. They were unsettling at best and remained firmly stuck in the “uncanny valley.” When it comes to erotica, though, we’re more forgiving of a bot’s imperfections. And the fact that porn bots are thriving, or that many people have already developed emotional connections to ChatGPT, alongside the popularity of various virtual influencers, suggests that what some media outlets currently ridicule could become the norm tomorrow. The danger is that while we enjoy the upsides of a deliberately artificial companion - something that could indeed have positive aspects - someone behind the curtain may be shaping our choices.

If we’re going to live alongside these synthetic presences, our first demand should be absolute clarity about their artificial nature. Simply tagging a profile as “AI” (already common) isn’t enough; we need the kind of identity verification that should have been in place years ago. People have long been calling for verified social media profiles so we know who—or what—we’re interacting with, but tech companies have little incentive to complicate the user experience. Before long, this won’t just be about security or stopping trolls; it’ll be about telling human users from bots. Ironically, the rise of bots might finally accelerate a process that should have happened long ago.

Whether we’re talking about erotic chats or general social media conversations, the integration of bots into our daily lives isn’t automatically a bad thing - it can provide companionship, support, and even education. But it also carries risks. We need transparency and awareness if we want to coexist with these new forms of digital life without falling prey to an army of tireless manipulators serving the same old elites.