This article will be published in Domus 1077, on the newsstand from 4 March.

“Of course, this is the house where he was born. Now it’s a museum. If you want to see where he lived, go further up. Keep right. After two roundabouts. A villa with lots of windows. If you ring, his wife will open. It’s worth it.” His wife? “He was a wonderful surveyor.” The lady’s kindness is overwhelming. “He was always really advanced. I know because he built the place where I live. The shutters are all white, and so is all the furniture.”

After asking directions from two girls, who barely knew north from south, and two middle-aged men who just shook their heads, the owner of the building with white furnishings in her kindness can be excused for confusing the writer Meneghello with the surveyor Meneguzzo. We’re in front of the garden of I piccoli maestri (1964, The Outlaws) – a sublime but horrifying fresco of a partisan adolescence – and Casabianca, a 19th-century building turned museum of graphic art, its neglect reflected in the glass cube of an insurance agency. A villa in pure Kazakh style, it sits among others that Balkanise the urban plan of this perfectly metaphysical province.

None of the postmodern villas is actually the work of the innocent surveyor, whose oval office is shielded behind a high hedge opposite the Umberto I-era cemetery. Here, bypassing a basement garage that is really an extension of the burial niches, I reach the tombstone of Luigi Meneghello and his wife Katia Bleier. Not in the house with large windows after the second roundabout.

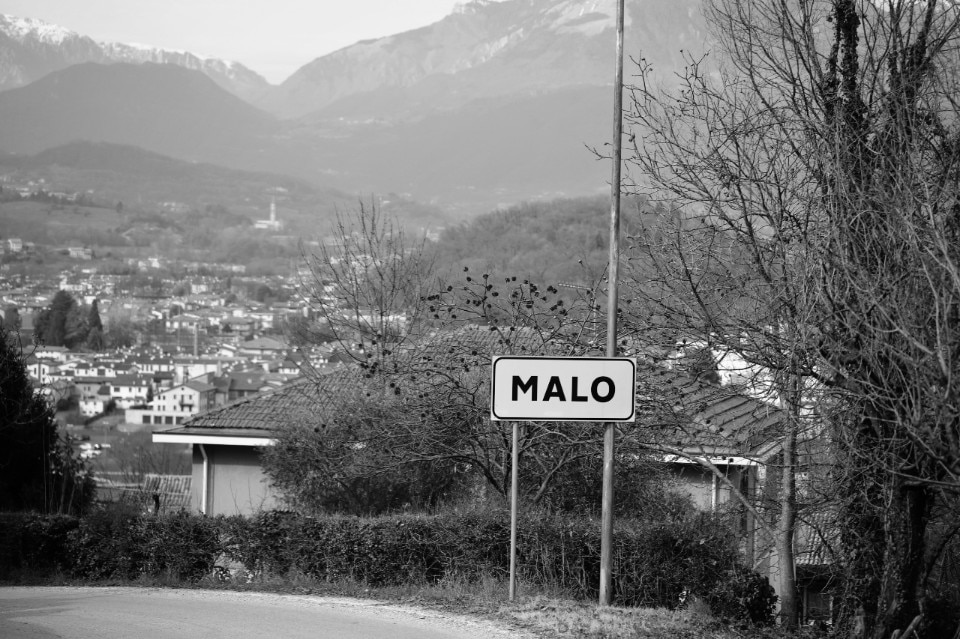

It’s 2 p.m. on an ordinary winter Saturday in Malo, Meneghello’s birthplace made famous by his first book Libera nos a malo (1963, Deliver Us). His prayer was answered, since he fled to Reading, England, to heal his spirit. There he taught Italian, abandoning Malo to a destiny without redemption. The only difference, perhaps, is that Meneghello explained the people and culture of upper Vicenza between the 1930s and 1960s, recounting the shadows cast on the houses, the pattern of the streets and doors, and “the shape of the sounds and these thoughts... for a moment truer than true”. But today all that has been replaced by “urban consolidation”, as defined by the Veneto Region’s Environmental and Strategic Evaluation.

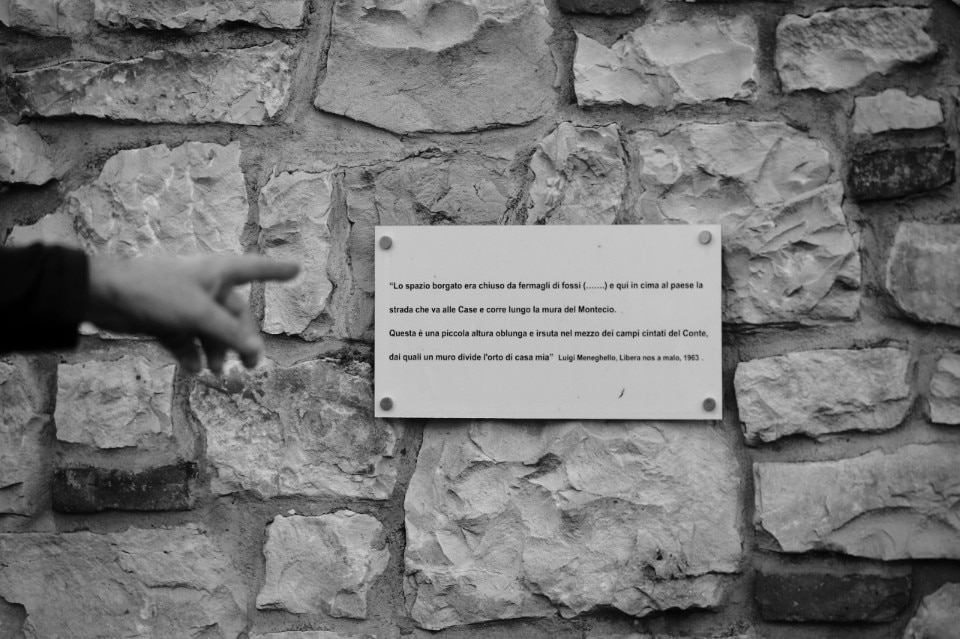

The borough space was enclosed by ditches […] and here at the top of the village the road goes to the Houses and runs along the Montecio walls. This is a small oblong and hirsute rise in the middle of the Count's walled fields, from which a wall divides the vegetable garden of my house

Luigi Meneghello

From Meneghello’s Malo to the Malo of today, the municipality’s 30 square kilometres have become “like a region where there is no clear distinction between the built-up areas, which sprawl seamlessly along the SP46 highway”. Even San Tomio, one of the three hamlets that now make part of Malo, has become “a single urban entity in morphological-developmental terms, united by the commercial strip along the SP46”. Those houses whose proportions Meneghello saw as the dimension of “otherworldly spheres that have more meaning than can be expressed and should be transcribed in a Neoplatonic key” are today villas in the other two hamlets of Case di Malo to the north, near the boundary with the town of San Vito di Leguzzano, and Molina to the east, near Thiene. Rather than being in the province of Vicenza, you feel you are in some vague region between Romagna and Tajikistan. As stated in the Strategic Evaluation of 2010, it appears as “almost a single urban entity, morphologically autonomous”.

Only the historic centre of Malo remains almost intact, though perhaps in the past you could at least get a coffee on Saturday afternoon. Today everything is closed even in the central piazza. Here, on signs celebrating his centenary, Meneghello gazes sternly at an outsize clown mask. It’s Carnival after all.

I look for the house of another great Veneto writer and again I’m surprised by the change in narrative. Born in Vicenza, Goffredo Parise lived in Rome and Milan, where he met the love of his life, the painter Giosetta Fioroni, who adorned his house together with Mario Schifano and other friends. A reporter for the Corriere della Sera in China, Vietnam, Japan, Biafra, Laos and Chile, Parise ended his days in Salgareda, a small town in the province of Treviso on the banks of the Piave. First he lived at Casa delle Fate, a spartan and poetic farmhouse on the floodplain, with an atmosphere redolent of Il ragazzo morto e le comete (1950, The Dead Boy and the Comets). Years later, after four bypasses and dialysis, he moved to Ponte di Piave, to another house with two gardens where his ashes still rest today.

The lack of desires is a sign of the end of youth and the first and very distant warning of the true end of life.

Goffredo Parise

Here, once you pass the empty bag of potato chips outside the gate, there’s a well-kept civic museum, as restrained as its writer but skilfully narrated by a devoted official. Upstairs it has a small, well-stocked library. Opposite, a new public kindergarten built on advanced architectural principles faces a park of tennis courts and supermarkets that simulate those in the Nevada desert.

While Meneghello worked on the fusion between literary language and dialect, making Malo the symbol of the transition from peasant society to unbridled modernisation, Parise recounted his places, depicting all the facets of daily life from which incomprehensible and often mysterious motifs emerged. His was a fusion of realism and the grotesque that reproduced an evolution of the setting where he chose to end his days.

Thirty-four years later, in 2020, Salgareda’s urban policy continued to stir controversy. A committee of 250 citizens and associations collected signatures to raise awareness of the need to adopt policies to protect the territory and identity of Veneto, which Parise saw as the only homeland its inhabitants would ever fight for. Strolling about Gonfo, Ponte di Piave and Salgareda today, visiting the nearby outlet mall and even managing to get a coffee opposite the Church of San Michele Arcangelo, that desire seems to have taken other forms, perhaps to the point of becoming extinct. “The lack of desires is a sign of the end of youth and the first and very distant warning of the true end of life,” Parise wrote. Let’s hope he was wrong, at least about this.