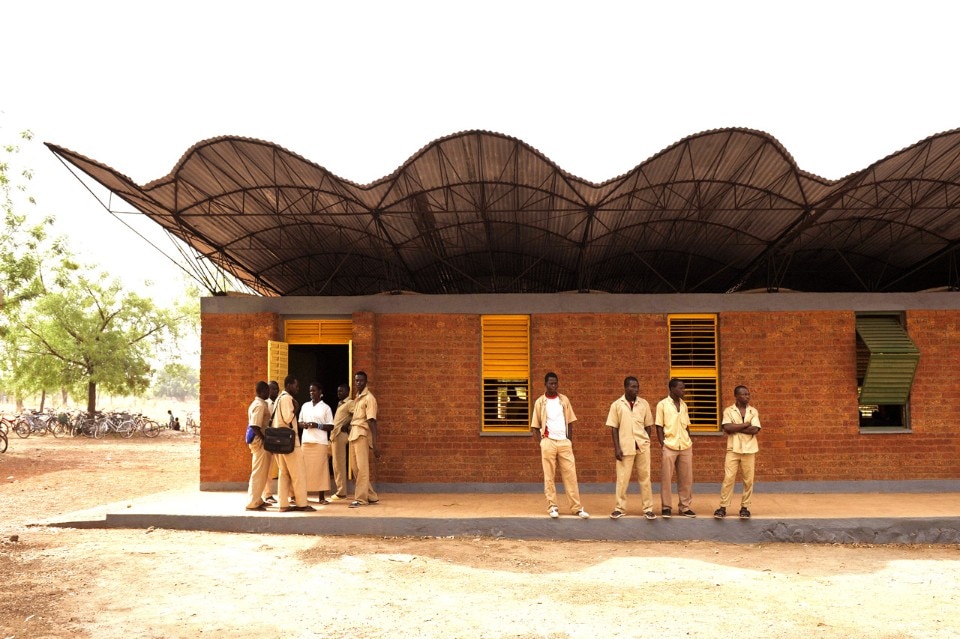

His works appear as a sort of contemporary cultural heritage. The big idea is to erect buildings whose quality and aesthetics are never inferior to the level proposed in places and countries with far greater financial muscle. This model has been increasingly adopted by numerous world-renowned African professionals, who, since they work in Africa, are demanding equality with Western standards. Over the years, the architect Francis Kéré has worked according to this vital paradigm.

During Milano Arch Week (12–18 June 2017) – organised by Milan Polytechnic, the City Council and the Milan Triennale – Francis Kéré held a conference titled “Built to Inspire”. We went to meet him there.

Riccarda Mandrini: Africa is seen as the continent of the future. Internal migration between countries is soaring (Global Bilateral Migration Database, World Bank), and people are abandoning their villages to go and live in cities, many of which already count millions of inhabitants. In such a difficult context requiring complex solutions, but above all the capacity to provide housing for an ever growing number of people, does it make sense to think in terms of “building to inspire”?

Diébédo Francis Kéré: There’s no innovation without inspiration. And without innovation there’s no growth. So we have no choice but to find inspiration and inspire. If we don’t, there will be no stimulus for innovation. Which means no future. Without inspiration, we’ll never be able to manage the problems of cities, which continue to grow at a tremendous rate with populations in many cases reaching several millions. We need inspiration to identify solutions to these growth-related problems. Africa needs inspiration.

Riccarda Mandrini: In many of your projects in Africa, in Burkina Faso, your work has incorporated the idea of collective memory. However, in a historical period with vast movements of people within Africa – a continent with 54 different countries – is the idea of collective memory still valid when talking about contemporary architecture and buildings which are used by large numbers of people with different cultures, religions and aesthetics? Regarding the idea of collective memory, when you create something for the people, isn’t it better or even imperative to refer to the concept of identity? The identity of a modern Africa that looks to the future?

Diébédo Francis Kéré: The role and importance of collective memory is a fluctuating concept. In a period of sweeping changes, it takes shape in an attachment to nature, which is an element that everyone can identify with. Of course, there’s a more individual collective memory that relates to the people. Being aware of collective memory – in the sense of knowing the history and stories of the places in which we work – allows us to find solutions right from the design phase.

It must be said that Africa’s cultural heritage is still linked to colonisation. Countries that were colonised by France are more tied to France, and the same goes for Portugal, or the countries that were colonies or protectorates of the United Kingdom. This factor impacts language and certain customs. The model of a contemporary African identity is energetically put forward, but with different significance in different countries. For example, Nigeria or South Africa experience the problem in a different way compared to Burkina Faso or Senegal. Economic differences also play an important role in building a modern identity between the various African countries. But the same consideration also applies within single countries. As you mentioned, Africa is the continent of the future, and the West’s idea of Africa and Africans should be revised. I believe that as Africans we have take our time to cultivate our own identity.

Riccarda Mandrini: How has your relationship with sustainability changed over time?

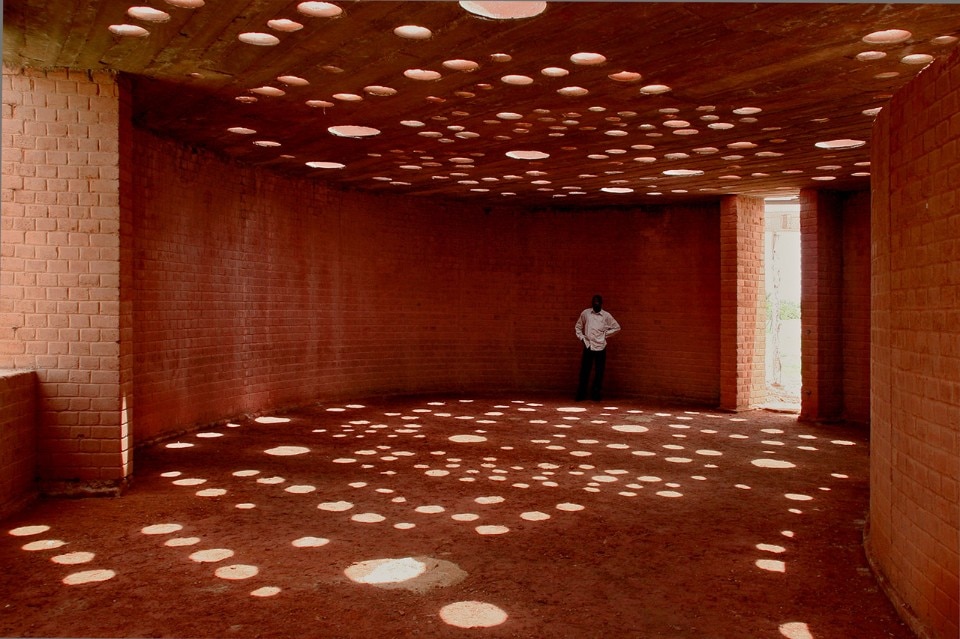

Diébédo Francis Kéré: I live by sustainability every day. It’s a stance that is reflected in my work, as well as in my actions and choices. One of the first things is human sustainability, which means providing people with training and education, and then creating work. But I also engage with the climate to conceive spaces that don’t require mechanical control in order to function. Sustainability is a complex argument that I deal with on a daily basis, almost without having time to think about it.

Riccarda Mandrini: Is it an inescapable attitude?

Diébédo Francis Kéré: Definitely.

Riccarda Mandrini: Let’s talk about aesthetics. In your conference in Milan, you spoke about the tree as a special point of reference for you.

Diébédo Francis Kéré: Yes, trees in nature are one of my aesthetic markers. The tree was also a central element in my design for the Serpentine Pavilion. The pavilion’s roof is inspired by a tree’s foliage, forming a sort of large canopy that creates a habitat. A second point of reference for me is African fabric with its thick, strong weaves.

Riccarda Mandrini: And sometimes rough…

Diébédo Francis Kéré: Sometimes, yes. And the colour indigo, too. In the pavilion, we used blocks of wood and painted them in this colour.

Riccarda Mandrini: Indigo is a colour used by African artists such as Aboubakar Fofana in his textile works and Abdoulaye Konatéin in some of his tapestries.

Diébédo Francis Kéré: Indigo is a natural colour, and fundamental in African culture. If someone has an important appointment, especially a young man, they dress in blue. For the Serpentine Pavilion, I’d talk more about inspiration than aesthetics, which are those of an open, welcoming space. It’s inclusive.

Riccarda Mandrini: You have said that you see yourself as a “bridge” between two worlds, two cultures and two realities. Do you still think of yourself in this way? Is the Serpentine Pavilion somehow a narration of this story?

Diébédo Francis Kéré: Absolutely, yes.