Adam Greenfield: Absolutely. All of these parties have a vital role to play in the creation and stewardship of networked place, but if there’s any such thing as a “smart city” at all, it’s one able to recognize that its intelligence vests in citizens themselves. As far as I can see, government oversight remains indispensable to ensure that the benefits and risks of networked technology are distributed equitably, and that the public’s interests are protected. My hope is that we’re collectively able to design urban-informatic systems that harness that intelligence, rather than undercutting it – that’s the aim I pursue in the book.

H.G.: Do your writing, thinking and making support then a kind of ‘ground up’ urbanism, with networked technology employed as an agent to empower citizens?

A.G.: Yes, but not only that. I believe this element is underrepresented in much contemporary discourse on the networked city, but you can’t build functioning urban-scale systems entirely from the bottom-up. Consider what it would look like, for example, if every block along an avenue decided for itself whether it wanted to support a bike lane or not. Imagine how that kind of patchwork-quilt approach would undermine the coherent functioning of the city.

In general, I would prefer to see networked systems designed so that people were able to turn them to their own ends, and to ensure their own wellbeing rather than having someone else’s idea of wellbeing imposed on them. This needn’t involve any particularly dramatic intervention, just a subtle reframing.

For example, we can compare the way CCTV security cameras are generally deployed to the way an organization called Digital Divide Partnership uses cameras in the lobbies of New York City housing projects. Where the feed from a CCTV camera is generally seen by the police — or worse, some outsourced security firm — the Digital Divide cameras offer a feed to people living in the same building. The community itself is empowered to watch what transpires, and respond as they see fit. When someone is recognized on a Digital Divide feed, it’s not by a facial-recognition algorithm, or some uniformed staffer in a distant control room — it’s by their neighbours.

By extension, I believe we’d be on firmer ground if more systems were designed with this kind of direct-accountability loop built into them.

H.G.: You resist the idea that networked devices and cloud technologies encourage "watchfulness from above". What kinds of strategies can designers take to place urban data in the hands of citizens?

A.G.: I still believe strongly in openness both as a technical provision and as an ethos - though this seems to be drifting out of fashion. The most concrete example I can think of remains the “View Source” command built into browsers. During the early years of the WWW, when pages were still mostly defined by simple HTML, View Source was a profoundly demystifying thing. You could reach into a page and see how it worked. And in the process, you might even learn how HTML itself worked.

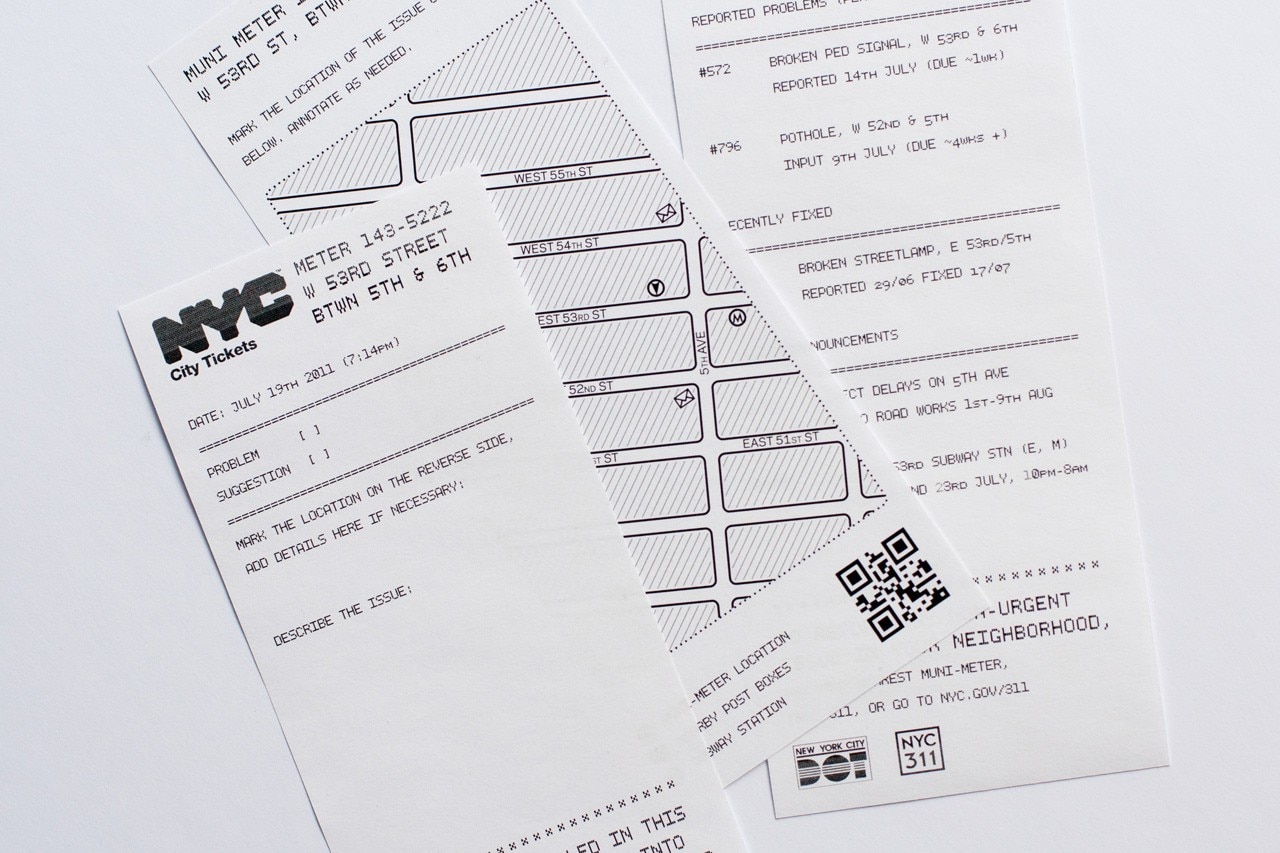

I do think that when you design information-technical systems so that they’re modular and self-describing, you wind up empowering people to disassemble them, learn how they work, and go about making their own things. When that openness is expressed at the level of data — when the data gathered by a given system is freely licensed, freely available, freely repurposable — then people will find a way to use it for their own benefit.

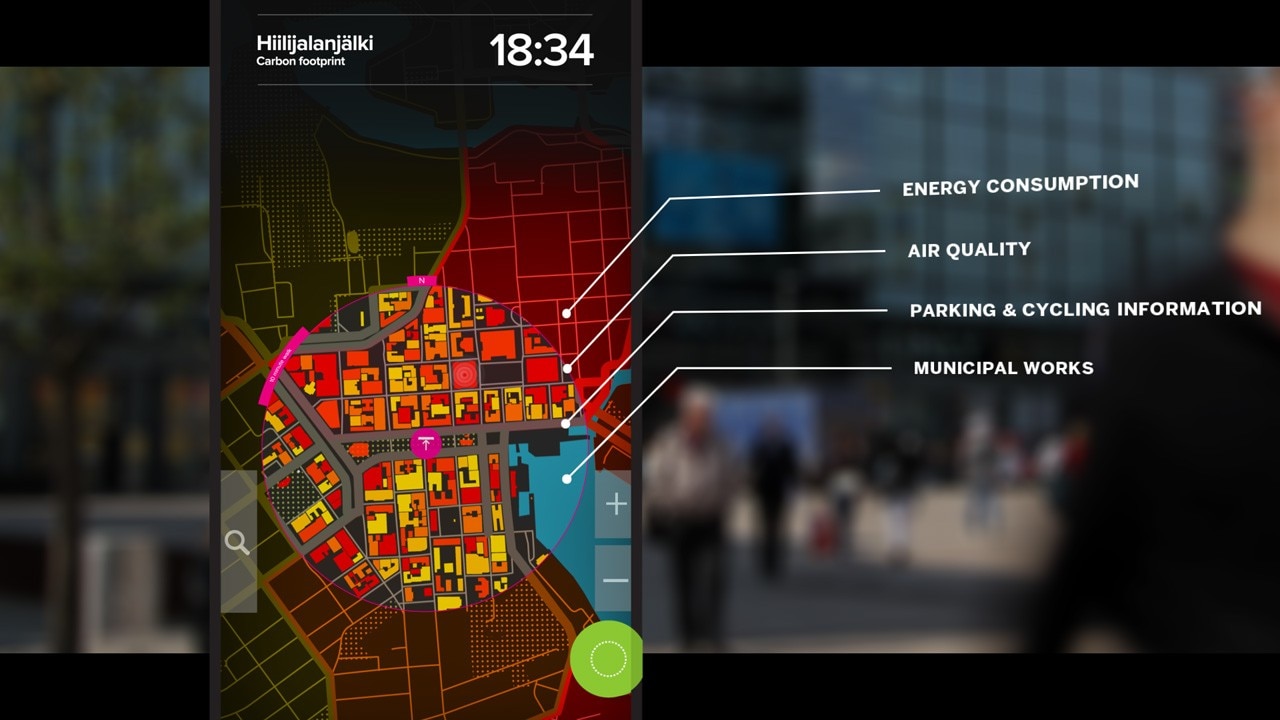

So instead of a city’s feeds about the location of bicycle accidents or traffic jams only being reserved for municipal administrators, offer it to all as a consolidated API. Let us use the data that we generate to make better decisions. That, to me, is how you empower citizens and harness the city’s existing intelligence.

H.G.: Have you seen any current or recent examples of good human-oriented urban design?

A.G.: I understand that the decisions made in the CitiBike bike-sharing service here in New York City, about where to site bike stations, were based on both bottom-up collaborative mapping and data analysis. I want to believe that’s so, because the placement of the CitiBike stations is pretty close to perfect.

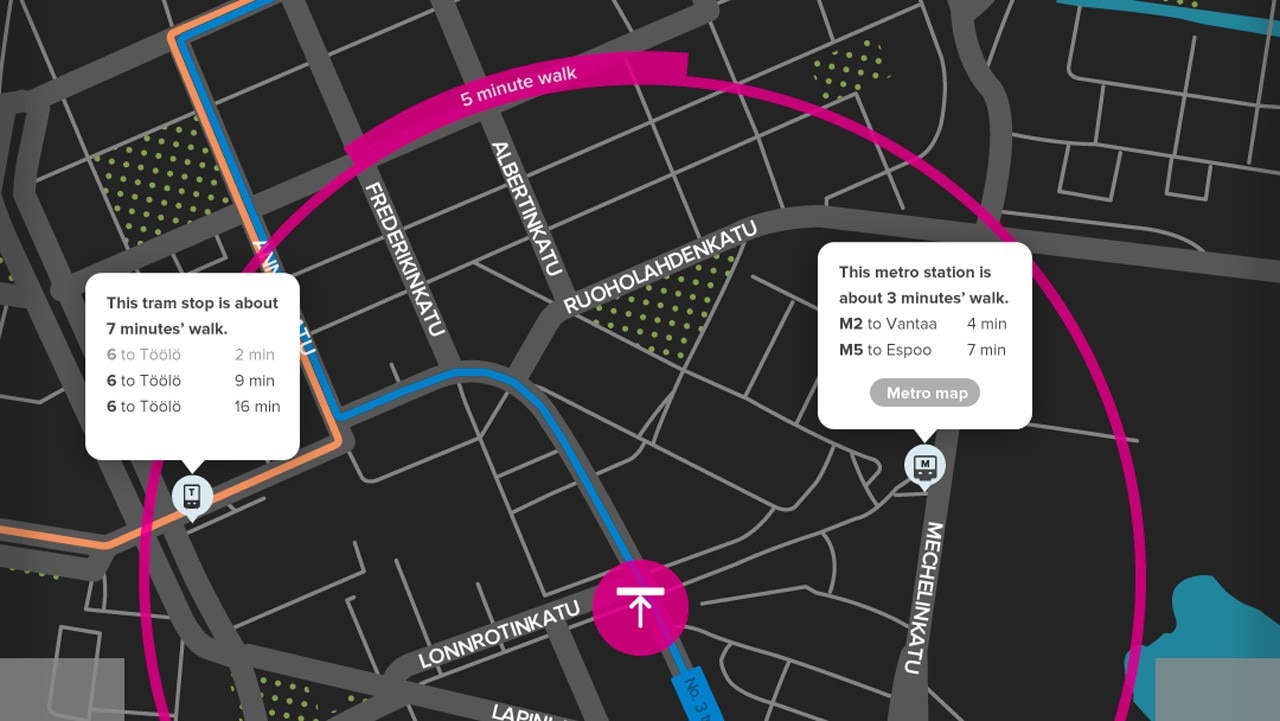

In general, urban cartography is improving. The “Legible City” system produced by City ID in Bristol, UK, is the gold standard in this respect. It’s responsible for originating most of the best practices we now see applied to urban maps: the pedestrian orientation, the walking radii with times and calorie counts, immediate You Are Here location and direction of view, clear building and neighbourhood identification, appropriate colourways. That goes on to influence things like Pentagram’s recent maps for CitiBike. If we could only bring the same level of craft to digital cartography, it would be a major step forward.

H.G.: What was your aim with Urbanscale’s Urbanflow screens? Urbanflow seems to chime with the call for “digital islands” as part of this Domus competition - to offer technological services to citizens and public bodies.

A.G.: Urbanflow, like everything we did at Urbanscale, was an attempt to push the discourse a little further, to demonstrate that there are healthy sustainable business cases for networked urban informatics, nested within the overarching insistence that such systems should firstly be designed for citizen benefit.

H.G.: You could say that the ideal would be to use the possibilities of near-future technology to return the city to the kind of democratic assembly we might associate with the polis of Ancient Greece. What do you think?

A.G.: I think that’s both a valuable aspiration for this class of technologies, and a reasonable description of my own ambition as far as their design is concerned. What we need to design are processes and technical systems that support the self-realization of vastly different collectives of people – not just an elite set. This is an extremely complicated challenge.

I guess that it’ll always be difficult to institute viable systems of direct democratic self-determination at any level much above a reasonably compact village, no matter what mediating technology you have access to. I’d imagine we’re talking about a group size right around the Dunbar number of 150. So what I’d love to see is municipal governance reconceived as a federation of groups at about that size, with the deliberation of each supported by the best available techniques of data collection, visualization and analysis.

H.G.: On a personal/professional level, how do you negotiate the place of writing and the place of designing in your work?

A.G.: I try in my own work to consciously design my values into systems intended to be deployed at commercial scale — to declare what those values are, and how they operate in the system’s intended functioning — and to let people choose for themselves what they feel comfortable embracing.

More broadly, it seems to me like my work is about trying to bring thoughtfulness back into the often too-rapid development process. How will lives and choices deform around such-and-such a product offering? What uses will people devise for this thing that you would not have anticipated, whether in Espoo or Seoul or Cupertino? How does this work lift some of the burdens that people everywhere are forced to negotiate, without saddling them with new ones? Above all, can my work do anything at all to level the playing field, redress some of the inequities of access and power and privilege we see everywhere around us in the world? As far as I’m concerned this is the only kind of work worth doing.

Adam Greenfield is a writer, urbanist and founder of urban systems design practice Urbanscale in New York. His second book The City is Here For You To Use will be released as a series of digital pamphlets with the first, ‘Against the Smart City’, published by Do Projects and Urbanscale this autumn.