Costanza La Mantia: The parallel between the philosophy of a co-generation network, and a networked society, where the resources of each form a stock of "collective goods" is really apt. Basically, the gist of the discussion is the same and points out the need for both new socio-political paradigms as well as for emerging models for alternative development (and not only in terms of energy).

Obviously, the Egyptian situation has specific causes linked to an explicitly repressive policy towards individual freedom in a context in which social inequity and human and civil rights violations by the government are much more evident than in our country. But at the same time, the Egyptian Revolution shares with other protest movements some of the motivations and methods that characterized 2011 as moment of collective reawakening. Not surprisingly, above and beyond basic differences, the Egyptian experience has been cited by other movements such as 15 Mayo and Occupy Wall Street with slogans like "We are all Tahrir" or "Walk like an Egyptian".

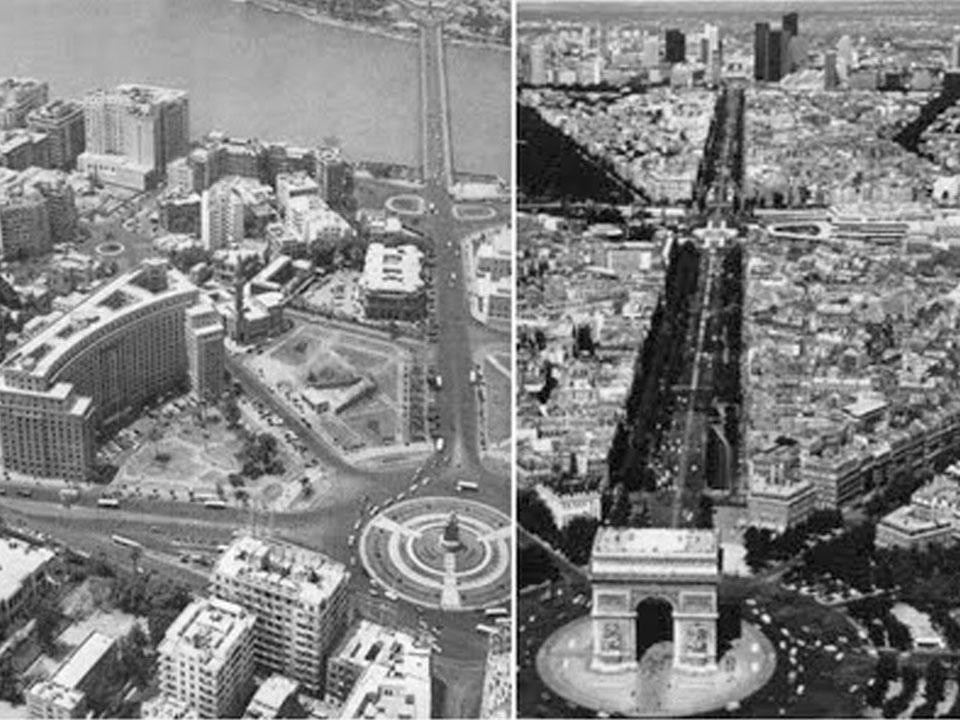

Tahrir Square is one of Cairo's most important squares. Originally part of the Nile river bed, the site was urbanized in the 19th century and became a working class neighborhood named el Louq. During the Sultanate of Al-Nasser Mohamed Ibn Qalàwùn, it became one of the richest and most luxuriant gardens in Cairo to return, in just a few decades, to conditions of decay, a mosaic of gardens and wetlands. It remained like that until the period of Ismail Pascià, the Khedive (1863-1879), who promoted an overall project to develop the city into the "Paris of the Middle East" transforming the neighborhood then called Ismailia into today's Downtown. At the time, the area, inhabited by princes, nobles and renowned personalities, was the site of the most important government buildings and services.

In 1952, sweeping away the monarchy of King Farouk, the Nasser coup d'ètat opened Egypt to a period of so-called "pan-Arab socialism" which was reflected in the modernist and international style of the State buildings of the era. Nasser completed the road system in the city center and the squares, including Ismailia Square, at the time renamed Midan el Tahrir (Liberation Square) metaphorically expressing liberation from British rule. After the confiscation of property of foreign residents in the name of the revolution, Downtown lost its cosmopolitan population. Consequently, thousands of wealthy Egyptian families began their exodus from the city, moving to luxurious areas like Zamalek or newly built suburbs like Nasser City. This was the moment in which Cairo began to lose its center, expanding into the desert through a system of new suburbs and "New Towns."

In the mid-1980s, under Mubarak, the garden was transformed into a large parking lot for tourist buses visiting the Museum, thus removing the public space. The garden's closure to the public was part of Mubarak policy that sought to discourage public gatherings. At this point, Tahrir housed the central symbols of power and was also the symbol of a government stance totally oblivious to the quality of life of its citizens.

It is no coincidence that the revolution began in that place on January 25, 2011.

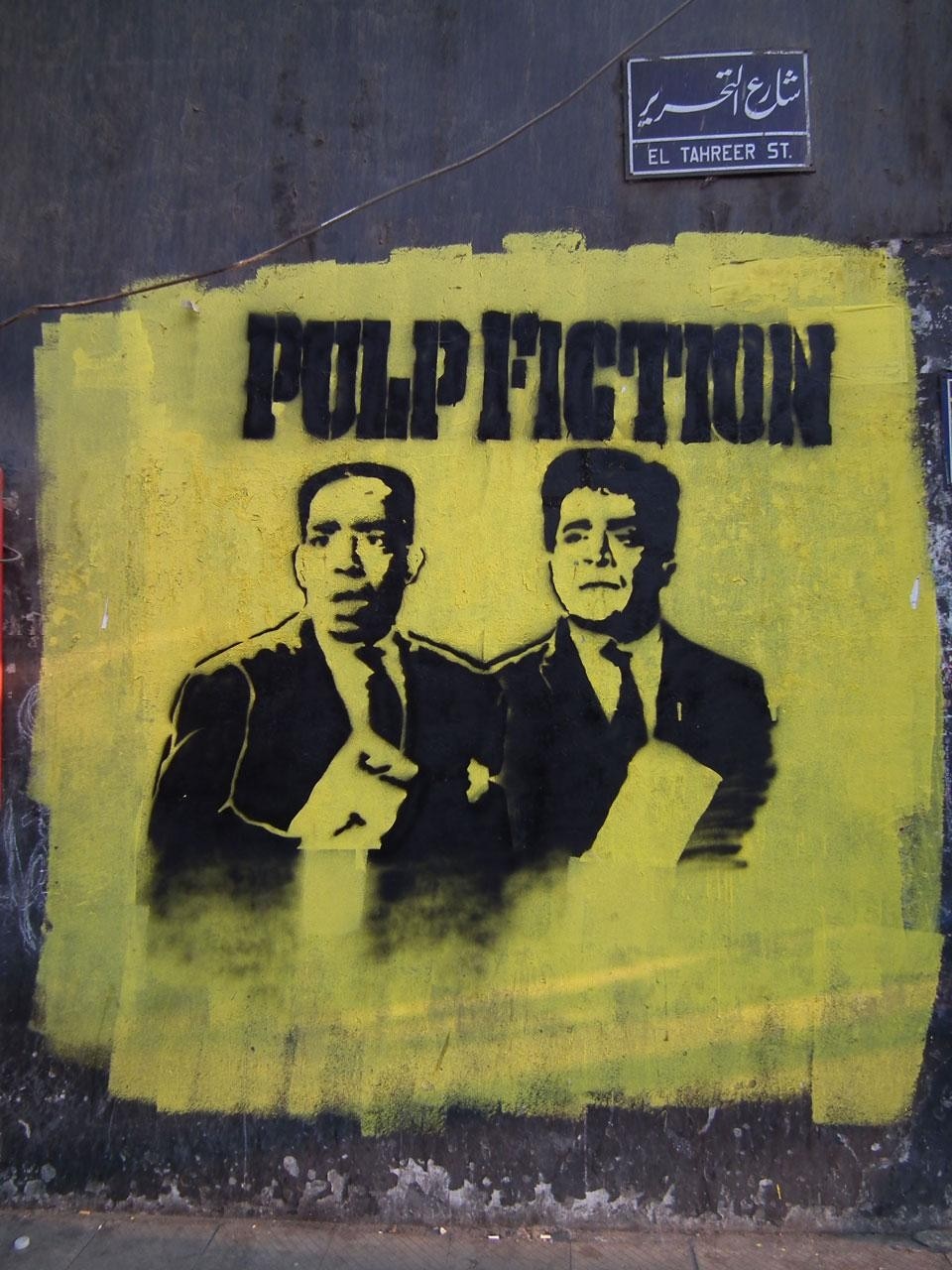

Subsequently, the square was, more than once, transformed into a "city within a city". During the first 18 days of occupation, thousands of Cairo residents, strangers to each other, worked peacefully in the square to create a well-organized "village." They created makeshift camps in certain areas, as well as toilets, garbage collection, recycling and management systems, food and water distribution points, clinics, public areas for reading newspapers, works of art, child care (allowing mothers to remain in the square with their children) and much more.

It is no coincidence that the revolution began in that place on January 25, 2011. Subsequently, the square was, more than once, transformed into a "city within a city". During the first 18 days of occupation, thousands of Cairo residents, strangers to each other, worked peacefully in the square to create a well-organized "village"

There is no doubt that social media played a large role in the Revolution. First, it replaced the real space that was formally and politically denied by the Mubarack regime, which restricted people's freedom through actions and laws that strongly discouraged access to public space. Beyond the highly centralized urban policies, with their elitist and private character distinguished by the negation of any democratic characterization of urban space and, as repeatedly denounced by Amnesty International, by serious human rights violations, there was also the Emergency Law, which, for almost 40 years, explicitly prohibited assembly and any unauthorized gathering in public spaces.

In this context, the network's virtual space (of social media) became that space of freedom and equality that had no outlet in the city's physical space; it became a truly democratic space that also reduced the social distance between individuals and classes that would have never established any form of dialogue in the street. Yet the Revolution could not have existed if that virtual space had not been inextricably linked to the physical space of the square and the city; if people had not met, learned to collaborate and share, transcending differences, transforming Tahrir Square - both physically and in meaning - into that "city within a city" as it has often been defined by the media.

In truth, I would speak more about "self-governance" than self-organization. Tahrir Square was a lesson in the harmonious process of "self-government" centered on a horizontal network structure as opposed to the more common hierarchical structure. With common purpose, the demonstrators organized themselves. For 28 consecutive days, and later, people came together, formed associations and working groups, taking responsibility for many aspects of daily life in the streets, organizing sanitation and medical services, security and protection as well as cultural and political activities in the square and in the various neighborhoods, developing a complex and highly effective communication system. They did not formally elect leaders and no one attempted to take on the role of leader but, in the square as well as in the neighborhoods, people freely organized themselves around "themes" (safety, emergency services, management and cleaning of common areas, etc..) contributing in different ways based on the skills and abilities of each participant.

In this sense, informal neighborhoods are a huge laboratory. There, in the absence of an institutional response to people's needs, residents endeavor to obtain the services that are not provided by the institutions, creating strong social and solidarity networks, demonstrating extraordinary "community" dynamics.

From a theoretical point of view, informality is a nonlinear complex system in which social dynamics change and intersect in unexpected ways: a perfect laboratory for studying the processes of adaptation and innovation required by the complexity and crisis of today's society which must move from a competitive model to a collaborative one. A model that can not only question the current definitions of development but that can, above all, activate and build upon so-called collective intelligence as a primary common good.

Costanza La Mantia is an urban planner and independent researcher with a long experience in Egypt and member of INURA, International Network for Urban Research and Action. She has closely followed the events in Cairo. She has studied in detail the successive transformations of Tahrir Square.