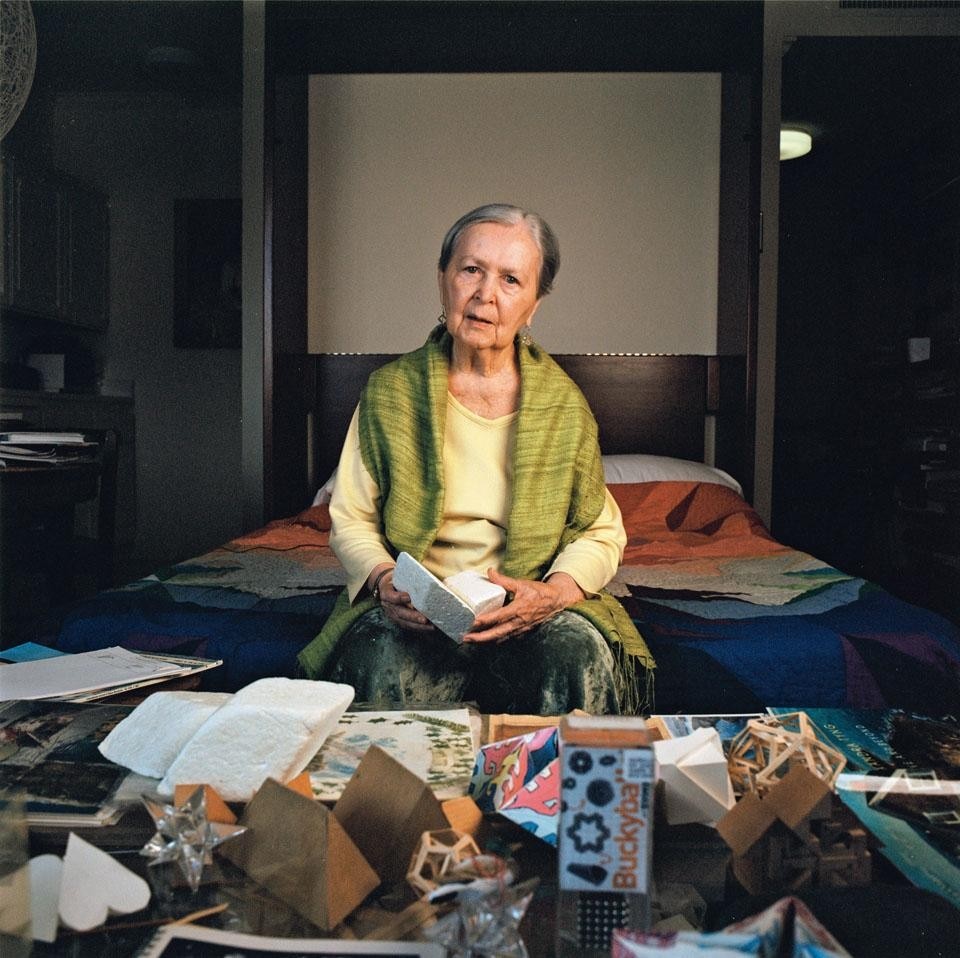

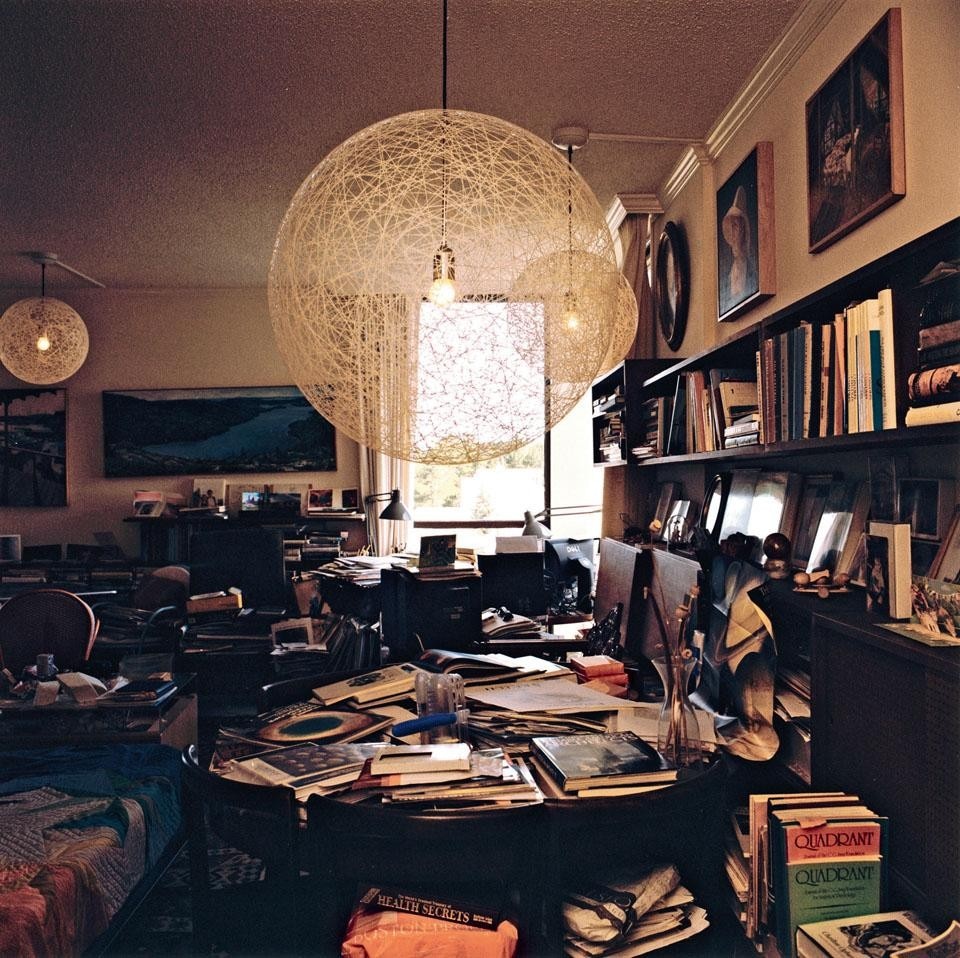

With this video, Ramak Fazel explores the domestic environment of Anne Tyng.

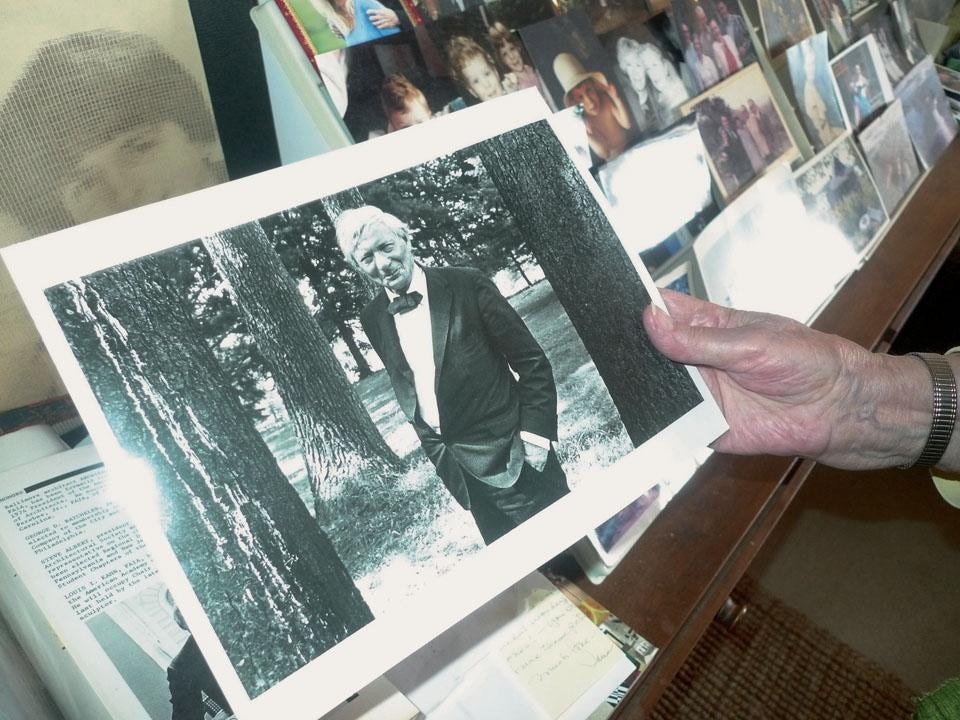

Anne Tyng (b. 1920 Jiangxi, China) is an architect and theorist. She was among the first women to receive a Masters of Architecture from Harvard University. In 1947, she began a decades-long collaboration with Louis I. Kahn, and was instrumental in the design of numerous projects in his office. She independently pioneered habitable space-frame architecture, and after 1968 focused her attention on research, earning a doctoral degree from the University of Pennsylvania where she taught for almost thirty years. In her research she developed a theory of hierarchies of symmetry—symmetries within symmetries—and a search for architectural insight and revelation in the consistency and beauty of all underlying form. The Graham Foundation, Chicago (from which she was one of the first women to receive a fellowship, in 1965) is currently exhibiting Anne Tyng, Inhabiting Geometry through June 18, 2011, the catalog for which co-published by the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia and the Graham Foundation, and distributed by DAP. Architect Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss, who collaborated closely with Anne Tyng as the guest curator to realize her exhibits at the ICA Philadelphia and at the Graham Foundation, interviewed Tyng at her home in Marin County, California.

This article was originally published in Domus 947, May 2011

Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss: In your dissertation and essays you connect organic cycles from nature to specific examples from the history of architecture. Have you done a design project based on this connection?

Anne Griswold Tyng: In my Urban Hierarchy project, there are rectangular or square houses connected by a roadway which is basically a helix with a circular access. Houses are set over each other along this spiralling roadway, and each section has a spiral access to the highway, giving the whole thing a cyclical sequence with recurring symmetries of squares, circles, helixes and spirals. The largest scale reveals and connects symmetries for human inhabitation.

Do you see it as a megastructure?

It is hierarchical and it connects a range of scales. Children can play on the bridges connecting the circular highways, which would be a safe open space between the spiral sections of houses. So there are spaces on a more intimate scale, which is related to the overall scale of the large structure. The models in the exhibition at ICA Philadelphia and now at the Graham Foundation in Chicago show that there is a whole town at each highway intersection.

You are critical of architects who base their designs solely on the golden section. You have even said that it is wrong to start from ideal proportions alone, and that it is better to arrive at them during the process. How is this demonstrated in your master plan?

Forms really operate in this way at almost every level. You start with something in the scale that you live in, or that you relate to, and then you go out in the world where you encounter various other scales. You have your block, your town, your village, your city, your whatever. I think we are so used to this hierarchy of scales that we don't even think of it in these terms.

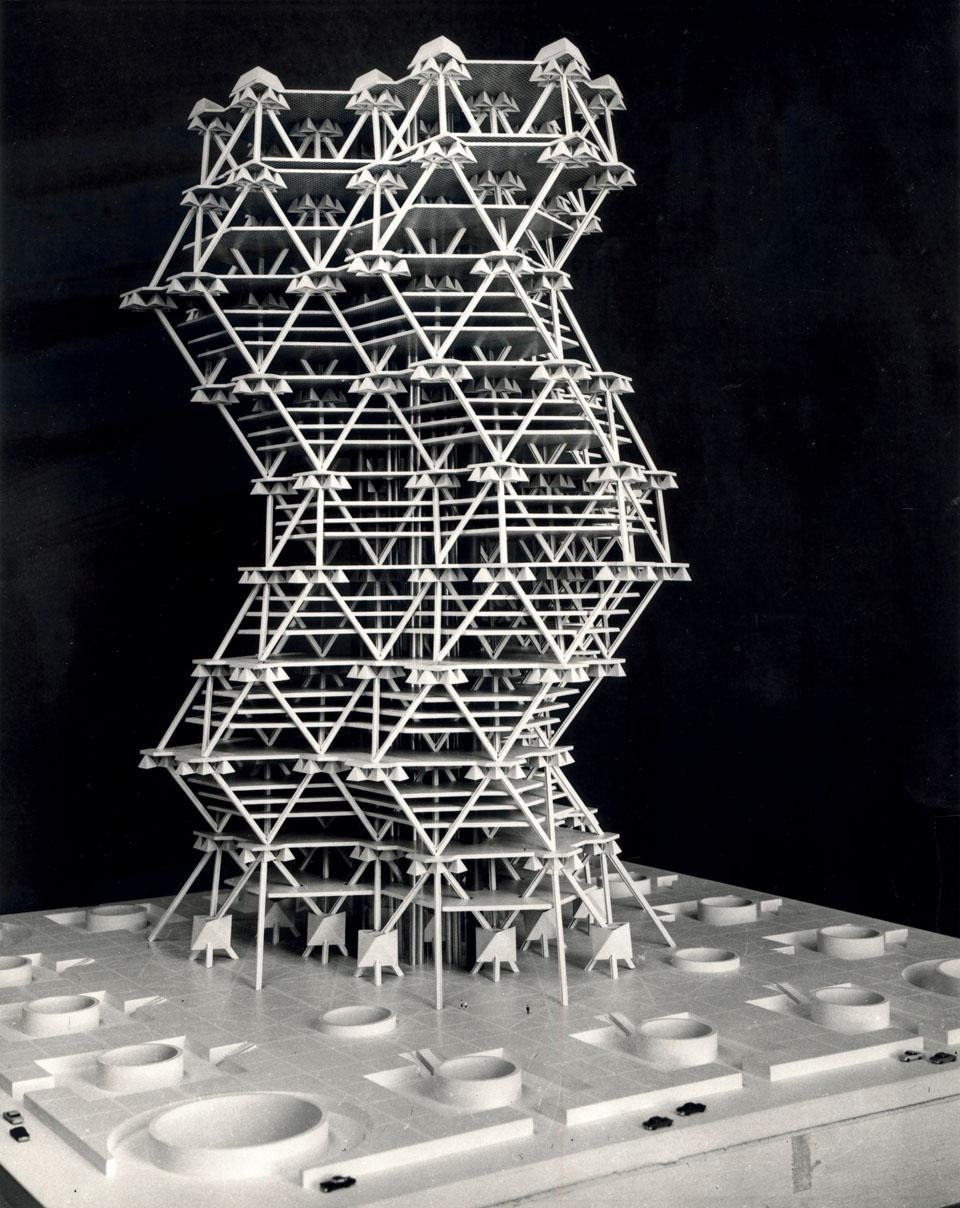

The tower is really just something I did. Bob Venturi had recently joined the office and he did a lot of work on the base of the tower. Lou also worked on the base, so he didn't have much to do with the tower either. He didn't really grasp the geometry that well.

Did you have discussions about this?

Oh yes. But this was a project I did in my spare time, and I didn't charge for it. It was just something I was developing in the office as part of my own work, like my project for the elementary school. The tower involved turning every level in order to connect it with the one below, making a continuous, integral structure. It's not about simply piling one piece on top of another. The vertical supports are part of the horizontal supports, so it is almost a kind of hollowed-out structure. Of course, you need to have as much usable space as possible, so the triangular supports are very widely spaced, and all the triangular elements are composed to form tetrahedrons. It was all three-dimensional. In plan, you get an efficient use of space. The buildings appear to turn because they follow their own structural geometric flow, making them look like they are almost alive. That was very appealing.

They almost look like they are dancing or twisting, even though they're very stable and not really doing anything. Basically the triangles form small-scale three-dimensional tetrahedrons that are brought together to make bigger ones, which in turn are united to form even bigger ones. So the project can be seen as a continuous structure with a hierarchical expression of geometry. Rather than being just one great mass, it gives you some sense of columns and floors.

What contact did you have with Buckminster Fuller?

He was on the West Coast. He had family there. He came to Philadelphia and we both had things printed in Maria Bottero's Zodiac magazine. In one issue I published the discovery of how you can divide all the edges of an octahedron into divine proportions, making it into an icosahedron. It was fun.

Did you ever have a face-to-face discussion with Fuller and La Ricolais? Were the three of you ever in the same place at the same time?

That would have been interesting, but we weren't. Actually there was always a sense of self-protection and jealousy. One was always worried about someone taking your ideas, which is something that can happen. I once had quite a discussion with La Ricolais about an aspect of geometry. I was taking it in another direction, and he was very critical. He picked up on some of my stuff. First of all there was the age-old cliché situation where men often thought they possessed women.

Like imaginary property?

Sometimes certain men do that without even realising.

We are in the 21st century now and...

That attitude still exists.

When you draw it, you feel it. I don't think I could manage to use computers as I am really turned off to them, to say the least. I get the feeling one misses something when using computers.

I think that right now we are at the end of the cycle that was dominated by feminine principles and now there is chaos, which comes before new renaissance. In terms of principles, simplicity will come out of this complexity. This has nothing to do with individual people. Obviously the masculine principle is extroverted while the feminine is introverted. Then you have the degrees of the connections to the unconscious, whether it is the individual unconscious or the collective unconscious, which is a more profound connection. So the cycle includes all of those stages.

When you say chaos, do you mean plurality or multiplicity? Do we live in a chaotic city today?

We more or less do live in the chaotic city. It is not being built the way the city was built in the past, and maybe will be constructed in the future. In a chaotic situation you have things coming together that would not normally do so. I think this is good, but it is also a difficulty because these things have to get together without destroying each other. Out of some of the negative things that happen you do get some kind of synthesis in order to move on. It becomes a positive synthesis for new attitudes and developments. The Jungian cycle is very meaningful to me because you could see it happening in history. In other words it is taken into a more collective realm where you don't necessarily take it all personally, although it might fit somewhere personally. In Jung's psychology there is also an individual cycle that does that too. The understanding of it is related to history and I don't think that Jung quite does it. I was trying to do that in a sense that you can experience it differently if you see it as a collective thing. It helps you to make sense of all the chaos in the world and gives you the tools to obtain a new synthesis out of it. Jung's discovery or proposal is wonderful; you can build on it and draw a lot of sense out of it for your own philosophy.

It's hard to say. I suppose if I were younger I would be doing it. But to me it is almost a limitation, because you would have to figure out what you are doing all the time. When you draw it, you feel it. A line is almost like making it. I don't think I could manage to use computers as I am really turned off to them, to say the least. I get the feeling one misses something when using computers.

What about the use of numbers?

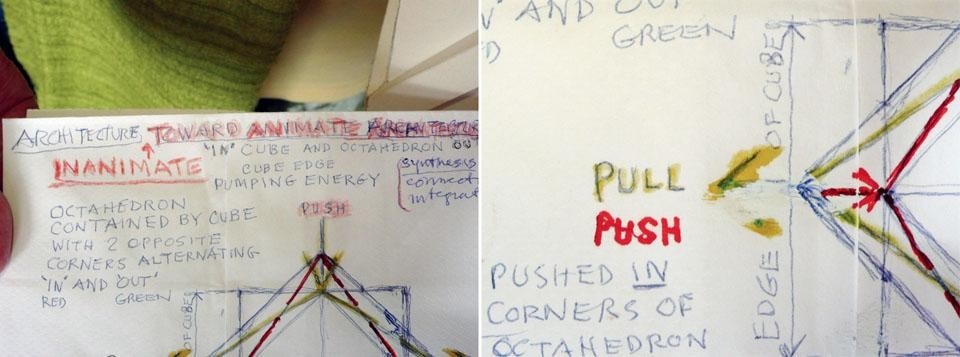

Numbers become more interesting when you think of them in terms of forms and proportions. I am really excited about my discovery of a "two volume cube", which has a face with divine proportions, while the edges are the square root in divine proportion and its volume is 2.05. As 0.05 is a very small value you can't really worry about it, because you need tolerances in architecture anyway. The "two volume cube" is far more interesting than the "one by one by one" cube because it connects you to numbers; it connects you to probability and all kinds of things that the other cube doesn't do at all. It is an entirely different story if you can connect to the Fibonacci sequence and the divine proportion sequence with a new cube.

Do you have a sketch or a drawing of it?

I have some, but I would like to do a better one. I was just working on that because I'm particularly keen on getting this cube documented.

Interview recorded in San Francisco Bay Area in March 2011