Jessamyn Fiore: Jeffrey Lew and his wife Rachel bought the building at 112 Greene Street in the very late 1960's. They were able to fill the upper floors with artists as renters but in 1970, when a rag picking business moved out, they did not know what to do with the ground floor and basement of the space. Meanwhile Lew was very active in the burgeoning SoHo artistic community of the time. These artists needed a venue that was different to the traditional white cube commercial galleries uptown. Many of them were creating works unsuitable for the commercial market at the time. They needed a space to create freely without the inhibition of maintaining a pristine environment.

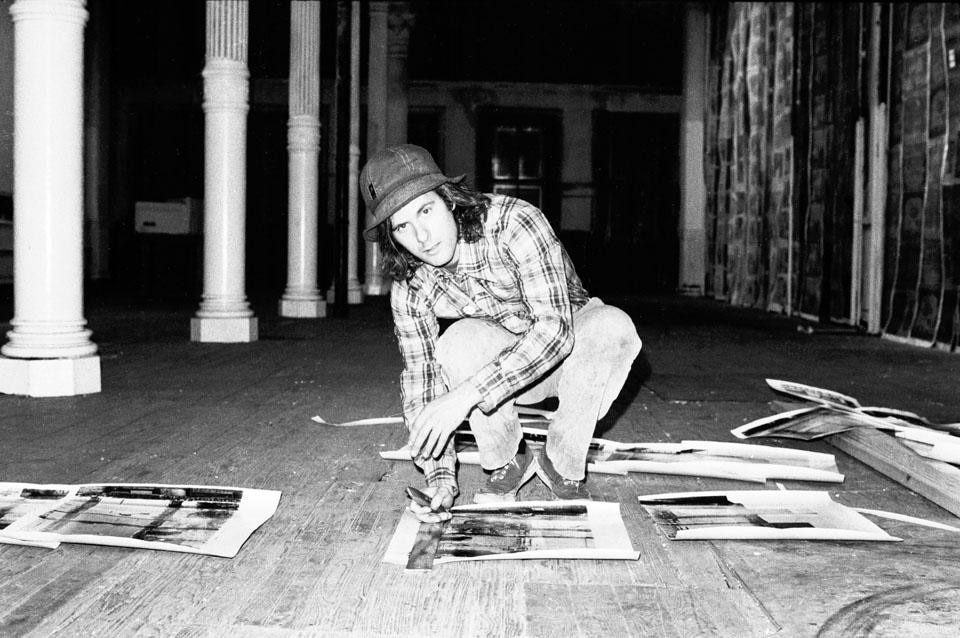

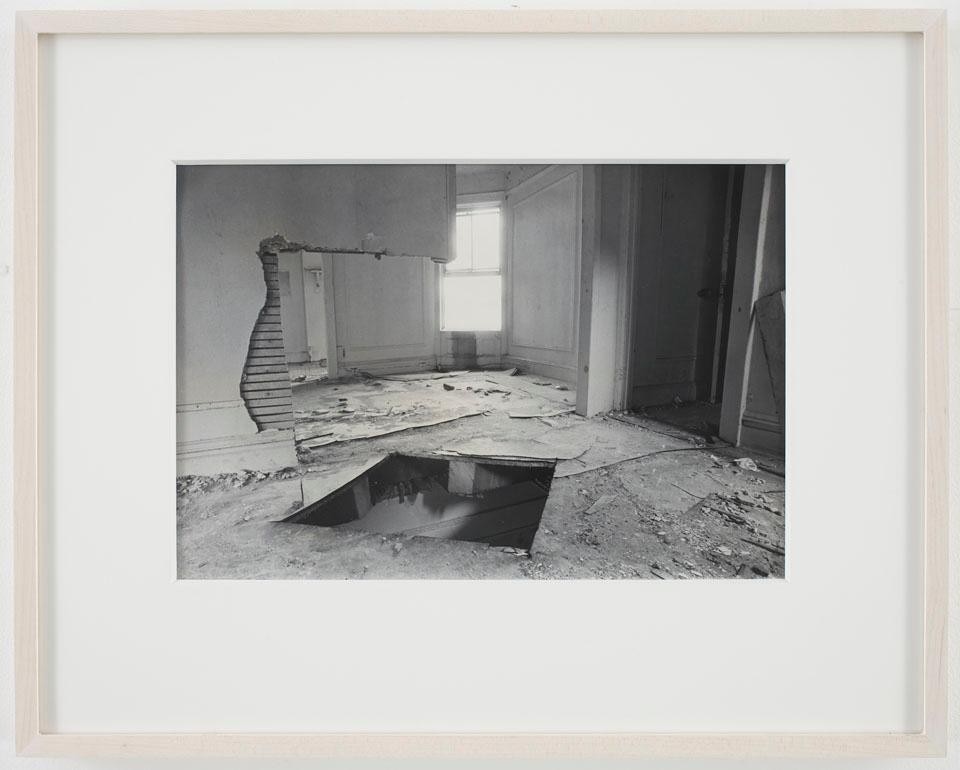

Lew opened the doors of 112 initially for his friends to have a space to work and show. He also brought to it his vision of a space that was open to anyone 24 hours a day; that was not academic and was not run by a committee. It was a large open space - bisected by a series of cast iron columns - that was left rough in its found condition. Its basement space that was in the beginning also open for exhibition, has been repeatedly described by artists I talked to as dark and dirty. But this was precisely the kind of venue required for these artists to blossom - they could cut through the floor or dig up the basement, include live animals in performance, create in and of a space that provided not a just a mere frame but rather a living context for the work presented.

The early years were curated by those who formed the core 112 community of artists - if you wanted a show you would have to talk to who was already there and work out a time when their work would come down and yours could go up. This community served not only to produce work but also to be its audience - they grew creatively together using 112 as a venue for their artistic experimentation and evolution.

I wanted this exhibition to express what was so vital and engaging about the artists and work produced at 112 Greene Street while simultaneously highlighting the importance of this venue to Gordon Matta-Clark's creative practice and career.

I first determined the time period, focusing on the early years when the space was self-curated by the artistic community involved in an organic and semi-chaotic fashion.

These were the years when Jeffrey Lew's original vision was fully reflected in the very nature of the space. The eventual need for government funding to sustain the venue meant the program had to be formalized and eventually an official committee formed to oversee its operation meaning Lew became less and less involved. Also by the middle to end of 1974 many members of the initial core group of artists began to move away in different directions in the pursuit of their individual careers. In addition this time period reflects Gordon Matta-Clark's direct involvement with 112 - he was a part of the first exhibition opened in October of 1970 and finished his run there with the Anarchitecture group exhibition in 1974.

Hundreds of artists either exhibited or performed at 112 Greene Street during these early years and there were scores of great works to chose from.

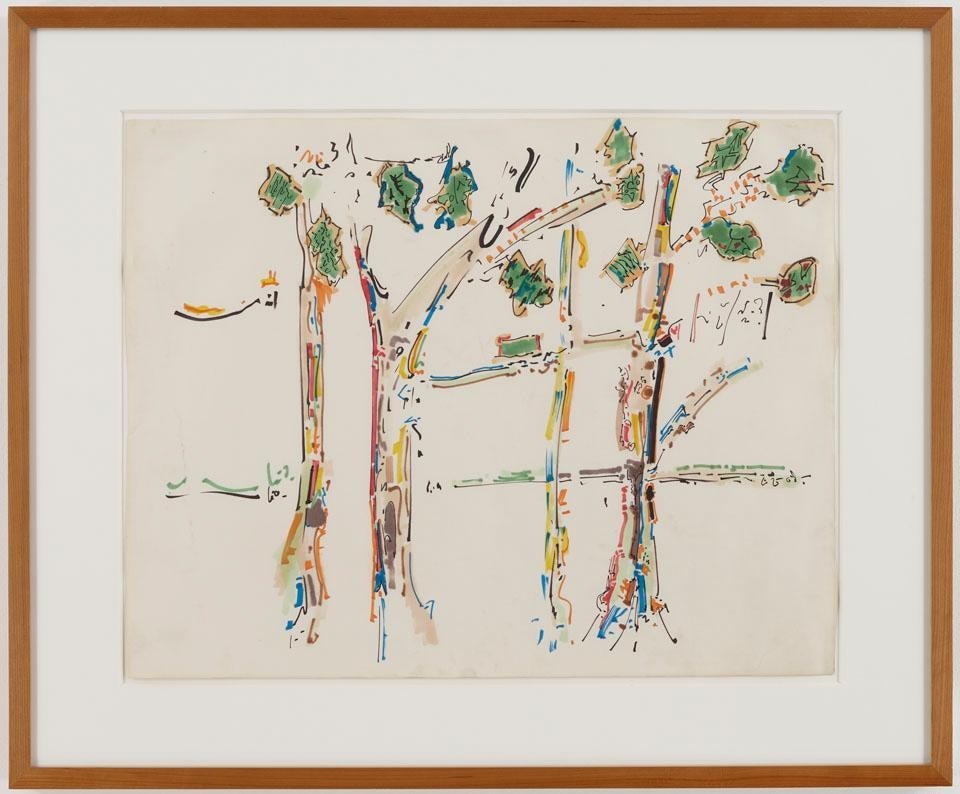

I wanted to reflect a core community of 112 Greene Street from those early years when Matta-Clark was a key figure - thus I selected artists who were greatly involved with 112 (each had multiple exhibitions both solo and group) and also had a strong personal and artistic relationship with Gordon. I wanted the selected works to reflect the main ideas being explored by the 112 artists at the time (investigations of space; performative sculpture; installations that directly invoke the crisis of urban decay; etc) while also conveying the energy and inspiration of this multi-disciplinary artistic community.

Of all the artists featured in this exhibition, only one, Richard Serra, was not a part of the core 112 Greene Street community. However the one work he made at 112 - the video performance Prisoner's Dilemma - is a wonderful reflection not only of that 112 community but the larger art world of the time.

Saret opened his own living space and studio up as a place of exhibition before 112 Greene Street opened its doors to artists. His space was too once the site of a rag picking operation and thus had similar architectural qualities to 112. Located on Spring Street, he called his space Spring Palace and invited such artists as Joan Jonas and George Trakas to show there.

This space became part of the inspiration behind 112 Greene Street and in fact Jeffrey Lew and Gordon Matta-Clark met there for the first time being introduced by Saret who had gone to Cornell University with Gordon where they had both studied architecture.

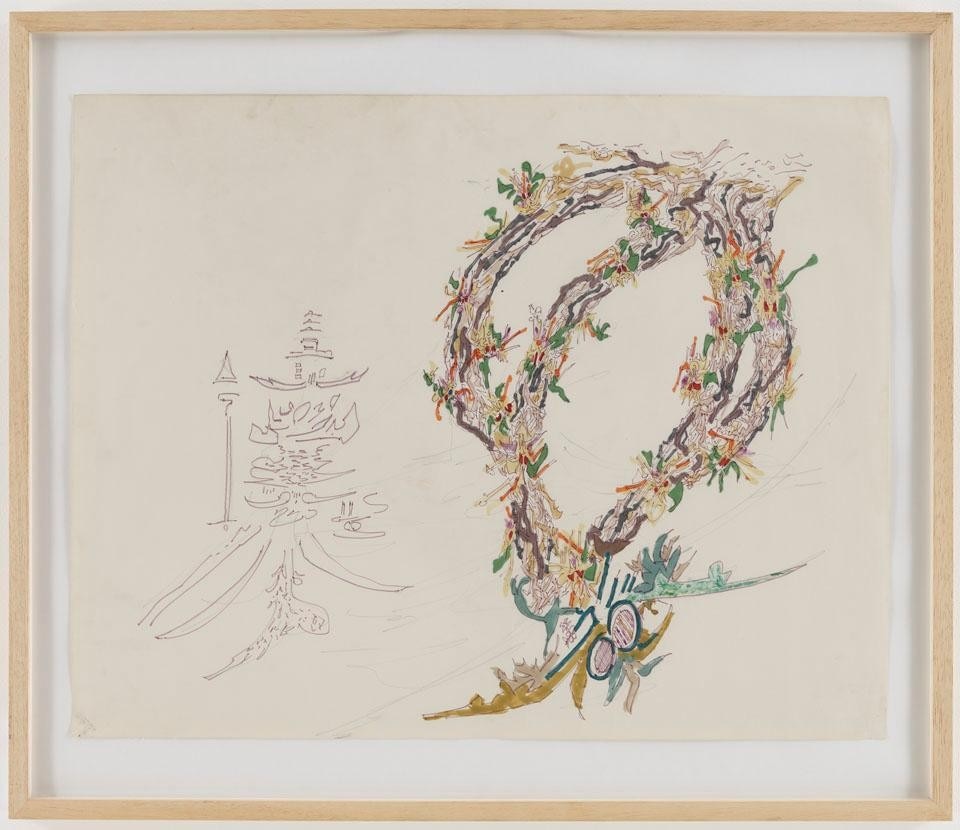

Saret's uncle was one of the first backers of 112 Greene Street and he helped Lew organize the first long-running ever-changing exhibition at the space. The sculpture of Saret's included in this exhibition is an example of his work during this time period where he used everyday industrial flexible materials such as chicken wire manipulating its form (in this case through various folding patterns) so that its stands solid and strong defying gravity. His contribution to the first 112 exhibition was another gravity defying sculpture: he hung a series of building cornicing from the ceiling that he had scavenged from a recent demolition in the Soho neighborhood. This work is unfortunately now lost but its connection to Matta-Clark's later architectural interventions is strong (he too would bring into 112 pieces of buildings that had been rendered obsolete with Bronx Floors also represented in this exhibition).

Bronx Floor: Floor Hole, 1972. Gelatin silver print, 41.3 x 51.4 x 3.8 cm. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

Ultimately though 112 Greene Street deserves a proper museum survey. The greatest outcome of this exhibition would be for it to inspire a larger institution to give an exhibition the space and support necessary to truly show the depth and breadth of work once contained within 112's walls.

Hundreds of artists passed through that space in even the few years I focused on- in reality this current exhibition is just the tip of iceberg.

3/4" video transferred to DVD, 40:15 min, black and white, sound Dimensions variable. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

In understanding Gordon Matta-Clark's work it is crucial to put him in context. He was a part of a vibrant and inspired community of artists who very much fed his own creativity and supported him (both mentally and physically) to accomplish his visionary works. 112 Greene Street was the only venue at the time where he was truly free to experiment and collaborate. This space was the outlet for his community - he was supported to show there - could take risks- and also get valuable feedback and criticism from his artistic peers. It was where he first began to really formulate the artistic ideas that carried through the rest of his career. You can easily draw a line from every work of his at 112 to a subsequent large-scale project; draw a line between those initial experiments to his larger vision. In order to understand his work you need to see the work of his peers and connect to the energy of his environment.

Food restaurant was opened after 112 Greene Street in September 1971 by Carol Gooden and Gordon Matta-Clark. It was the sister space in many ways - the same core members of 112 were involved with Food - such as Tina Girouard who had brought southern Cajun cooking to this community. In fact her living space on Chatham Square in China Town (shared by Mary Heilmann and Richard Landry among others) could be seen as the inspiration in some respects behind Food the same way Spring Palace was the inspiration behind 112.

Girouard and the other southerners moving to New York brought with them a social culture organized around preparing and sharing food - it was a way of life that proved exotic, inviting, and energizing to the northern artists. The centrality of food became a hallmark of many events and exhibitions surrounding this group of artists and can be found as a major component in Matta-Clark's own work. Food restaurant provided a venue for the social/culinary creative pursuits of this community in the same way 112 provided a venue for the sculptural/performative creative pursuits of that very same community. They are two sides of the same coin and both served as a creative platform for this inspired, energetic and fun loving group of artists.

As I mentioned before, the Anarchitecture group was composed of many of the core artists involved with 112 Greene Street. Many of their individual works/exhibitions for which 112 was a venue explore the same questions that Anarchitecture was formed to address. The Anarchitecture exhibition at 112 Greene Street was the last exhibition Gordon Matta-Clark, Jene Highstein, and Richard Nonas participated in - their careers all moved in different directions at that point. The exhibition was not documented which is a problem - so all we know of what Anarchitecture was is left to the individual artists memories and what work they held on to that is considered "anarchitecture". And there are of course many different interpretations by those who participated as to a definition of Anarchitecture - but perhaps that is most fitting. Whatever it "was"- it was a forum for creative debate, one that still survives today.

After the Anarchitecture exhibition Matta-Clark began his first large scale "cutting" work where he cut a house in Englewood, New Jersey, in half to produce "Splitting". This piece is one of his now most iconic works and signaled the new trajectory in his career. So in a way Anarchitecture summarizes a lot of the lessons learned and ideas formed during his years at 112 Greene Street that launched him into his large scale - and incredibly ambitious- architectural cuttings that came to define his legacy.

Well I became attracted to telling his story in the context of 112 Greene Street because I was running my own alternative art space in Dublin, Ireland, and suddenly had a whole new perspective on how being apart of such a project greatly effects those involved. This was an avenue into Matta-Clark's early work - really his formation as an artist - that I had never seen fully explored in an exhibition before and so I am delighted to be bringing it to light with a hope to explore it further.

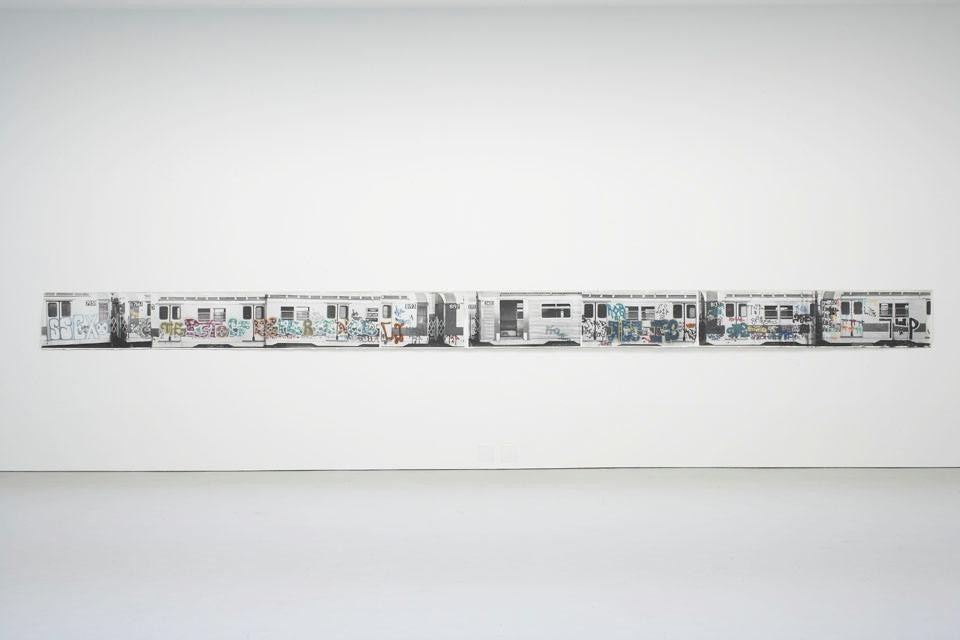

I suppose however, in terms of other unexplored directions, one could jump from the beginning of his career to the end. It is useless to sit around and try to figure out what he would have "next"- however his growing interest in the underground and tunnels is certainly a contender for what was inspiring him in those final years. I think there is room for exploration and reflection around these works with perhaps some tie-in to contemporary interest in the underground systems of cities. How is it possible to really see a city when you ignore its many layers buried beneath the surface? I think this is a question Matta-Clark began to beautifully explore before his life was cut short.

Gordon Matta-Clark

Tina Girouard

Suzanne Harris

Jene Highstein

Larry Miller

Richard Nonas

Alan Saret

Richard Serra

January 7 – February 12, 2011

curator: Jessamyn Fiore

David Zwirner

525 West 19th Street

New York, NY 10011