Through objects, images and exhibitions, Pierluigi Cerri has undoubtedly marked the language and history of Italian design in recent decades. Born in 1939 in Orta San Giulio, an architect with a Milanese polytechnic background, co-founder of Gregotti Associati, he has linked his name to memorable visual signs such as the image of the 1976 Venice Biennale, the editorial language of Electa under his artistic direction, contributions to magazines such as Rassegna and Casabella, and furnishings that have brought small revolutions in their realm, such as the Naòs multi-vocational tables designed with UniFor. His story and his own lifewere also tightly bound to Milan cityscape, as he recounted to Domus in April 2014, contributing to issue 979 with an itinerary through the city's less visible identities, represented by the unseen environments of five gardens.

Pierluigi Cerri's Milan

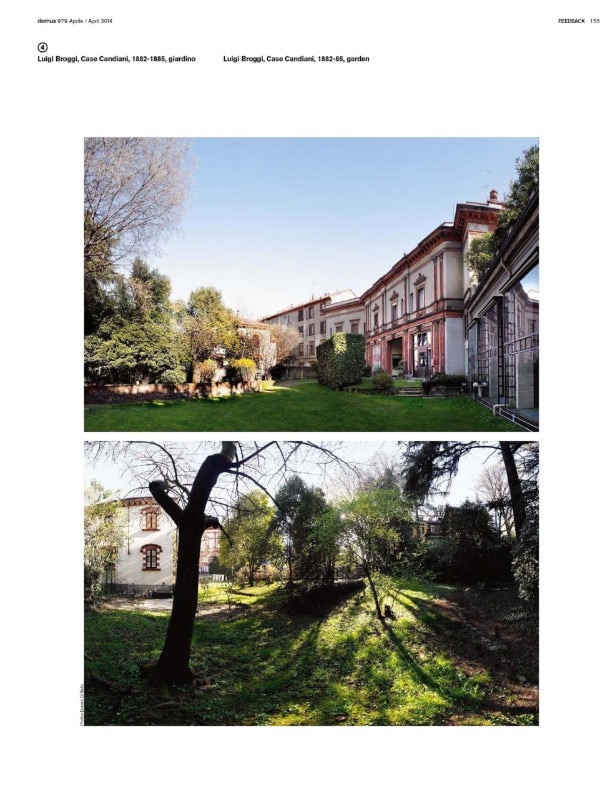

These days, people only write about the city to complain about congested traffic and the resulting air pollution, about ecological issues, safety, or infinite other problems. At the risk of seeming inclined to conservative thought, I consider the section of Milan where I grew up as a special part of the city that represents a whole. Its monuments, archaeological remains and historical sections are the parts that give it identity. This area of Milan is built along an axial road leading from the ancient Porta Vigentina to the centre, Piazza del Duomo. Since 1859, this avenue and the entire neighbourhood it crosses are called Magenta, in honour of the Battle of Magenta. The Magenta quarter is my part of Milan. It has nothing in common with the sumptuous display of Foro Bonaparte or the city’s neoclassical buildings or the Jugendstil quarter around Porta Venezia. It’s a low-profile neighbourhood. The buildings communicate the solid bourgeois origins of their inhabitants. The multiform facades were designed under the eclecticism that ruled at the end of the 19th century.

Surfacing along Corso Magenta, which is austerely devoid of majestic rows of trees, as are its confluent roads, are noteworthy remains of Milan during the Roman times, Middle Ages, Renaissance and the baroque period. Few are the constructions that testify to modernism.

Five secret gardens

As children, we used to go to school by foot, always in a rush. Our short-cut went from the Santa Maria delle Grazie church through the Chiostro del Bramante cloister. Here, for the sanctity of the place and its immaculate beauty, our pace slowed. The cloister is a secret garden, unexpected, immersed in silence and shaded by four magnificent magnolias.

Nowadays, with help of a tablet, it is quite easy to investigate buildings from above. But gardens reveal their own secrets. Corso Magenta and its crossroads show buildings of stonework facing the street and hide natura naturata or natura naturans in their inner courts, the trees of which tell stories of legendary designs and residual spaces.

The history of the garden of the Casa degli Atellani on Corso Magenta is legendary. The “flowering and delightful” garden extends from the Casa to a private road, Via De Grassi, redesigned by Piero Portaluppi as “a tree-lined rectangle where an ancient pergola covered with grapevines still endures, challenging Father Time. It is what remains of Leonardo da Vinci’s vine. Under this ancient pergola, it is certain that Leonardo sat and meditated, feeling his divine creations jumping around inside him.” All this enhances the feeling of a secret garden, whose light “will enter the rooms and find the lunettes frescoed by Luini with portraits of the Sforzesco Family.” We used to peek at this mysterious oasis from the shady side of the ultra-private Via De Grassi, which injected a bit of fear into our adolescent play. Secret gardens are “peeked at” because we do not want to violate their privacy.

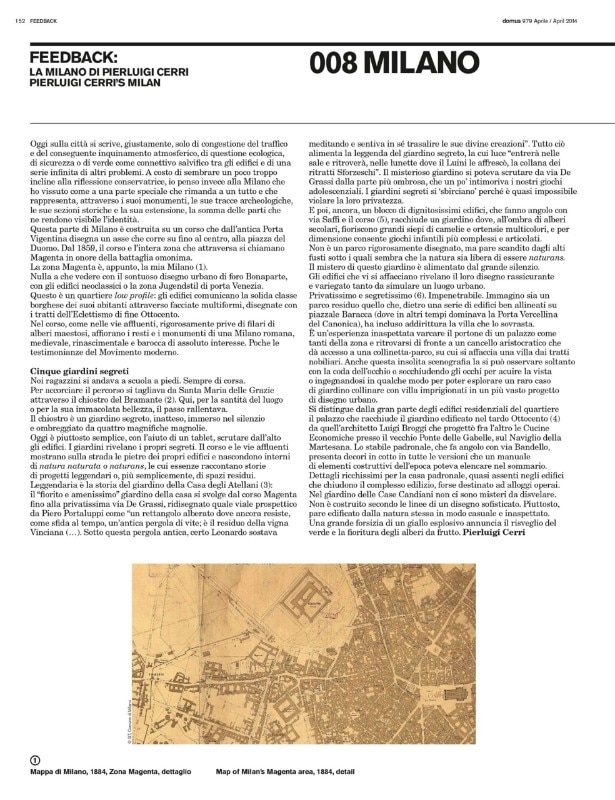

Then there are the dignified buildings that form a block on the corner of Via Aurelio Saffi, which runs into Corso Magenta, enclosing a garden where large hedges of camellias and multi-coloured hydrangeas bloom in the shade of age-old trees. Its size allowed for more complex and structured childhood games. This is not a designed park, but it feels organised by the tall trunks under which nature is free to be naturans. The mystery of this garden is enhanced by its great silence. The sight of the reassuring and variegated facades of the overlooking buildings adds a bit of urban flavour.

Very secluded, very secret. Impenetrable. I imagine this to be a leftover park behind the series of buildings neatly aligned along Piazzale Baracca, which was dominated by the Porta Vercellina del Canonica in times gone by. The park even includes the villa that was built to preside over the garden. It is an unexpected experience to cross the threshold of the main door of a residential building that is like so many others in this neighbourhood and find yourself in front of an aristocratic gate that gives access to a hillock park watched over by a mansion with noble features. The unusual scenery can be observed from the corner of your eye, or with eyes half closed to sharpen your sight, or in some other invented way in order to explore this rare case of a garden knoll-with-villa imprisoned in the vaster urban plan.

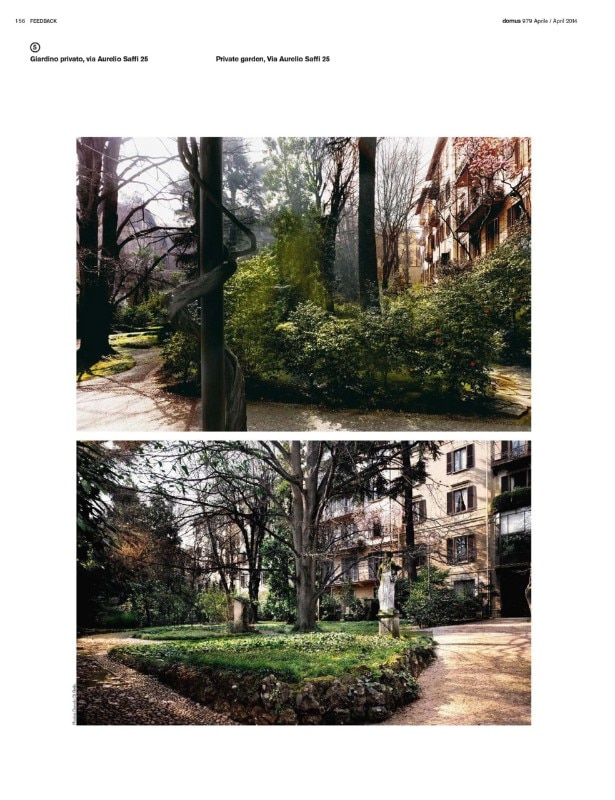

There is one building that stands out from the other residential buildings in this quarter: the one enclosing a garden on the corner of Via Matteo Bandello and Corso Magenta (4). It was erected in the late 19th century by the architect Luigi Broggi, who also designed wood-stoked kitchen stoves by the old bridge Ponte delle Gabelle on the canal of Naviglio della Martesana. The main entrance features a profusion of terracotta decorations – as many kinds as a manual of construction elements from those days could list. This abundance of rich detail is lavished on the main building, while being almost absent from the side buildings that close the complex. Maybe that part was housing for manual labourers.

In the garden of Case Candiani, no mysteries are to be unveiled. It is not laid out along the lines of a sophisticated plan. Rather it seems made by nature itself, in a random fashion, but with a few surprises. A huge forsythia of an explosive shade of yellow heralds the awakening of plants and the blossoming of fruit trees.

Cover picture: Private Garden, via Aurelio Saffi 25. Photo Donato Di Bello