Before the Campanas you could call it postmodern; after, it was easier to call it dream. Before the Campanas, it used to be “'informal”; after, it had become innovation and poetics of imperfection. Fernando, one of the two Brazilian brothers who made writing about design more fun, has died on 16 November at the age of 61. Since founding Estudio Campana in 1984 together with his brother Humberto, Fernando had brought a vital and irreverent flair to the world of design, weaving large velvet reptiles into the 7 square metres of the hybrid Boa, with the same refinement with which splinters of wood were randomly assembled to form an iconic chair like the Favela.

Domus has spent a lot of time with Fernando and Humberto, as it happened in June 2003 — it was issue 860 — when the two brothers inaugurated an exhibition of their work in the Brazilian capital, as their country was preparing to turn over a new leaf with Lula's first presidency.

It is no accident that one of the first cultural events staged in Brasilia after the recent election of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva as Brazil’s new president was an exhibition of the work of the Campana brothers, two young designers whose work is distinctively Brazilian yet has found resonance around the world. Da Silva’s commitment to addressing his country’s gross inequalities of wealth and looking beyond its elite to embrace its dispossessed certainly has parallels in the Campanas’ approach to design.

When Fernando and Humberto Campana’s work first began to attract international attention at the end of the 1980s, it was because they seemed to offer an alternative to a homogenous view of design, defined by global models and high-tech, that was producing an unstoppable, all-conquering flood of bland industrial objects, insensitive to the specifics of geography or climate and indifferent to local traditions or concerns. The Campanas looked for inspiration in the poverty that blights the favelas yet also gives life and energy to their work. In doing so, they seemed to prove that something else was possible.

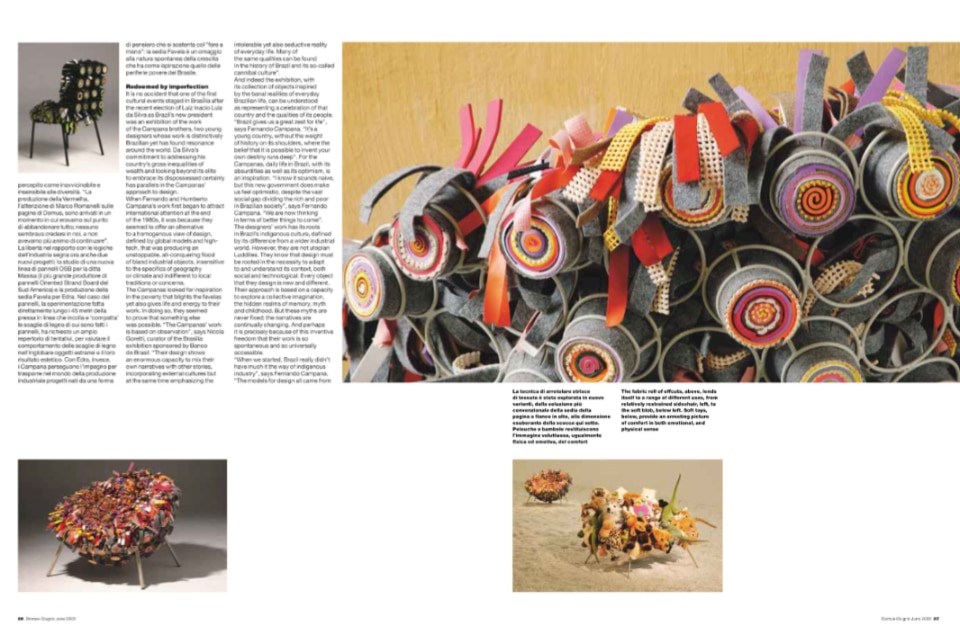

“The Campanas’ work is based on observation”, says Nicola Goretti, curator of the Brasilia exhibition sponsored by Banco do Brasil. “Their design shows an enormous capacity to mix their own narratives with other stories, incorporating external cultures but at the same time emphasizing the intolerable yet also seductive reality of everyday life. Many of the same qualities can be found in the history of Brazil and its so-called cannibal culture”. And indeed the exhibition, with its collection of objects inspired by the banal realities of everyday Brazilian life, can be understood as representing a celebration of that country and the qualities of its people.

“Brazil gives us a great zest for life”, says Fernando Campana. “It’s a young country, without the weight of history on its shoulders, where the belief that it is possible to invent your own destiny runs deep”. For the Campanas, daily life in Brazil, with its absurdities as well as its optimism, is an inspiration. “I know it sounds naive, but this new government does make us feel optimistic, despite the vast social gap dividing the rich and poor in Brazilian society”, says Fernando Campana. “We are now thinking in terms of better things to come”.

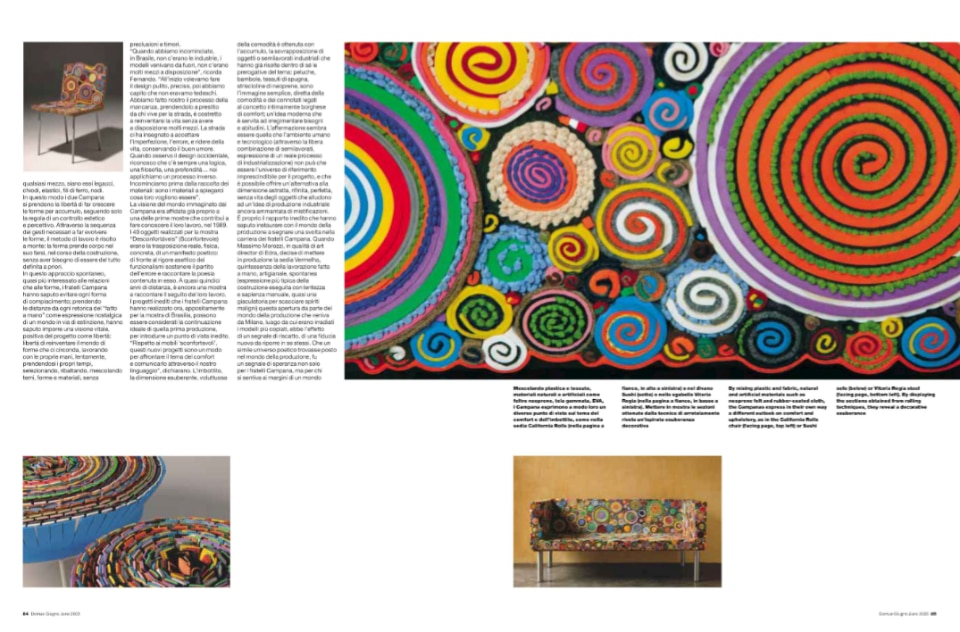

The designers’ work has its roots in Brazil’s indigenous culture, defined by its difference from a wider industrial world. However, they are not utopian Luddites. They know that design must be rooted in the necessity to adapt to and understand its context, both social and technological. Every object that they design is new and different. Their approach is based on a capacity to explore a collective imagination, the hidden realms of memory, myth and childhood. But these myths are never fixed; the narratives are continually changing. And perhaps it is precisely because of this inventive freedom that their work is so spontaneous and so universally accessible.

That kind of street life taught us to accept imperfections and mistakes, and to look at life with a sense of irony.

“When we started, Brazil really didn’t have much it the way of indigenous industry”, says Fernando Campana. “The models for design all came from abroad, and we had very few resources. At first we wanted to do clean, precise design, but then we realized that we were not Germans, so we adopted a strategy of need, borrowing from Brazil’s street people. They live on the streets and are forced to reinvent their lives for themselves, without having anything much to fall back on. That kind of street life taught us to accept imperfections and mistakes, and to look at life with a sense of irony. When I look at Western design, I can always see a logic in it, a philosophy and a certain depth. We have to do it the other way around. We start our designs from the materials that are available and that we can collect, because the materials tell us what they want to be”.

The leitmotifs of their work are weaving, accumulation and collecting, signs of a manufacturing system based on the most elementary of technology. The main concern to keep things together by any means available: straps, nails, elastic, wire, joints. In this way the Campanas have the freedom to grow their forms through a process of accretion. They create form spontaneously through the process of making, rather than through any a priori definition. This spontaneity has allowed the Campanas to avoid the more obvious pitfalls of a nostalgic craft-based approach to design. In their hands, design is about freedom, the freedom to reinvent the forms around them and to work with their own hands. They take their time, working slowly, so as to be able to select gradually the themes and materials that interest them; they are ready to explore but also to change their minds, to combine materials without preconceptions.

The Campanas first made their mark with another exhibition back in 1989. ‘Uncomfortable’ brought together 40 objects that were the authentic, physical transposition of a poetic manifesto. They were attempting to contrast the antiseptic rigour of functionalism with the poetic potential of error. Fifteen years later, the Brasilia show can be seen as a continuation of those early projects, though transformed by the introduction of a new element.

It is precisely because of this inventive freedom that their work is so spontaneous and so universally accessible.

“Compared to ‘Uncomfortable’, these new designs are a means of confronting the issue of comfort and expressing it in our own way”, say the Campanas. They achieve the voluptuous, exuberant, upholstered dimension of comfort through a process of accumulation and a superimposition of industrially produced or semi-finished objects. Furry animals, teddy bears, dolls, towelling and thin strips of neoprene create a plain, direct image or associations of bourgeois notions of comfort, a modern convention that has served to shape and condition our needs and habits.

Their idea seems to be that a human dimension to technology can offer a real alternative to the abstract, polished artefact and to the lifeless dimension of objects that allude to an idea of industrial manufacturing still shrouded in mystery and mystification.

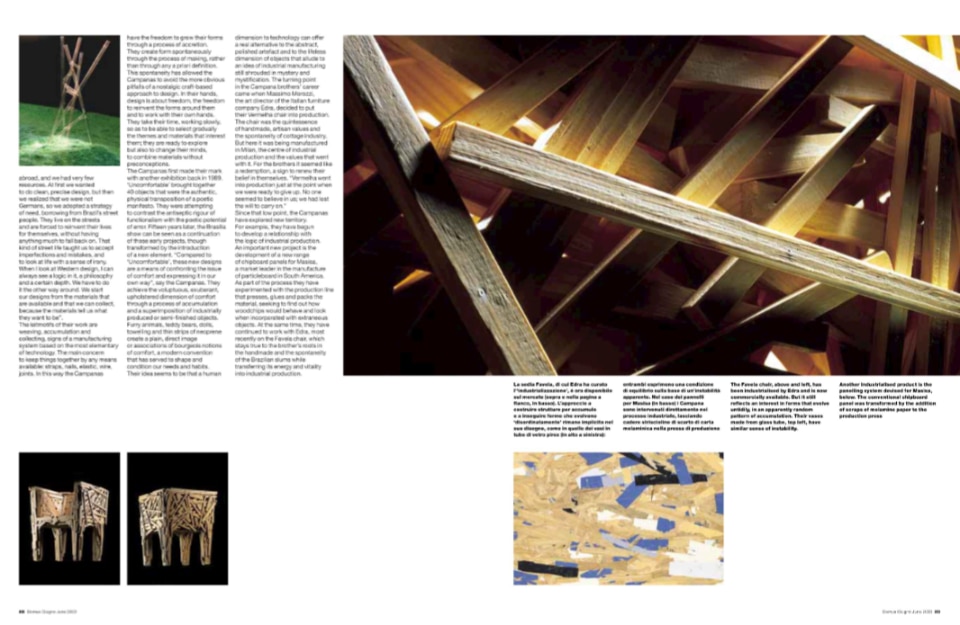

The turning point in the Campana brothers’ career came when Massimo Morozzi, the art director of the Italian furniture company Edra, decided to put their Vermelha chair into production. The chair was the quintessence of handmade, artisan values and the spontaneity of cottage industry. But here it was being manufactured in Milan, the centre of industrial production and the values that went with it. For the brothers it seemed like a redemption, a sign to renew their belief in themselves. “Vermelha went into production just at the point when we were ready to give up. No one seemed to believe in us; we had lost the will to carry on.” Since that low point, the Campanas have explored new territory. For example, they have begun to develop a relationship with the logic of industrial production.

An important new project is the development of a new range of chipboard panels for Masisa, a market leader in the manufacture of particleboard in South America. As part of the process they have experimented with the production line that presses, glues and packs the material, seeking to find out how woodchips would behave and look when incorporated with extraneous objects. At the same time, they have continued to work with Edra, most recently on the Favela chair, which stays true to the brother’s roots in the handmade and the spontaneity of the Brazilian slums while transferring its energy and vitality into industrial production.