This article was originally published in Domus 729 / July 1991

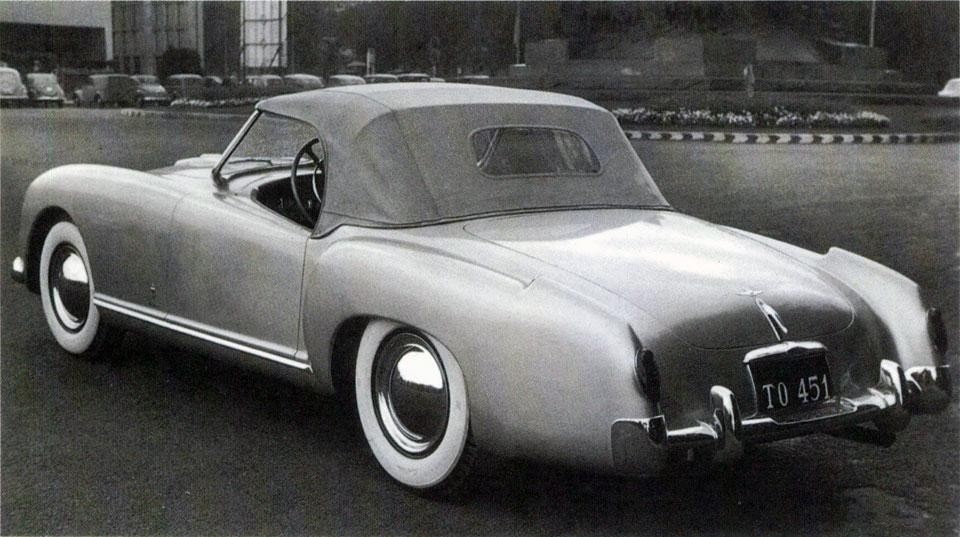

Pininfarina: design between invention and repetition

For years Angelo Tito Anselmi has been digging meticulously into Pininfarina's archives. The outcome is an exhibition of the firm's method which carefully explores the evolution of industrial products.

One object alone has been able to faithfully represent both the progress of techniques and the myths, dreams, illusions and contradictions of modernity — the automobile. No other artefact, not even the TV-set and the telephone, has so perfectly symbolized "human aggressiveness and the need for wandering isolation ... [embodying] the myth of heroism, of competitiveness and elegance, besides those of efficiency and timeliness". The car has become "the vanguard of that precarious ideology of progress for a social group tied to the conspicuousness of consumption". (V. Gregotti, 1978).