The Ningbo Museum sits on a massive unpopulated plaza in Yinzhou, a district in the city of Ningbo with a 5,000-year history that looks like it was established last year. The streets that surround it are wide enough to accommodate six lanes of traffic, but are virtually car-free. The sidewalk is lined with skinny leafless trees, shrubs and disconnected tiles of brownish-yellow grass. In the distance, the silhouettes of newly built residential towers and half-finished office buildings imply a bustling future, but for the moment the area exists in a kind of temporal limbo – its past abandoned, its future not yet arrived.

At the north end of the plaza is a broad, grey stone building occupied by the district government. It is boxy and relentlessly symmetrical in the typical style of municipal architecture in the PRC. It projects stability and strength both physically and symbolically: the building looks indestructible and the fact that the government resides in it reassures developers of the area's viability. The museum, a three-story, 30,000-square-metre block positioned on the plaza's northwestern edge, conveys the opposite. On approach, its form looks haphazard. It is apparently a box, but its sides are skewed and large chunks are missing. Its materials are inconsistent and ill-fitting. The facade is pocked with small, arbitrarily arranged windows that reveal nothing of the building's contents. It is an awkward building, but next to the muscularity of the government offices, it conveys a vulnerability that is touching, almost heart-warming, and as I approached the entrance I wondered whether this museum represents an entirely different sort of strength, the strength to embrace the unusual.

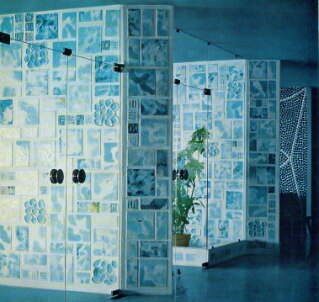

Most of the Ningbo Museum's exterior is composed of debris collected from destruction sites around the region. The pieces were assembled using a technique known as wa pan, a method developed by the region's farmers to cope with the destruction caused by typhoons