This report looks at and brings back into focus the pieces designed for interiors or for production (almost always by Poggi of Pavia) by one of the leading—and most forgotten—Italian architects. Like few others, Albini has the outstanding capacity to decline all the themes of design.

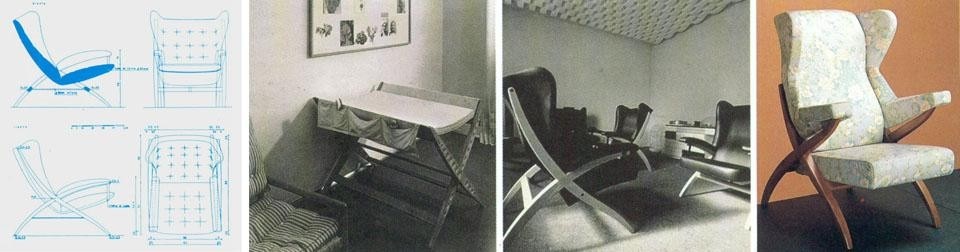

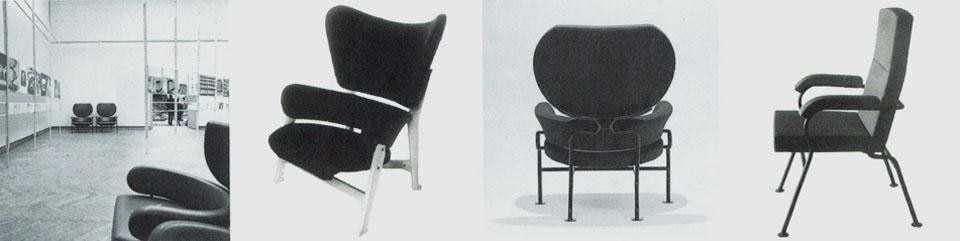

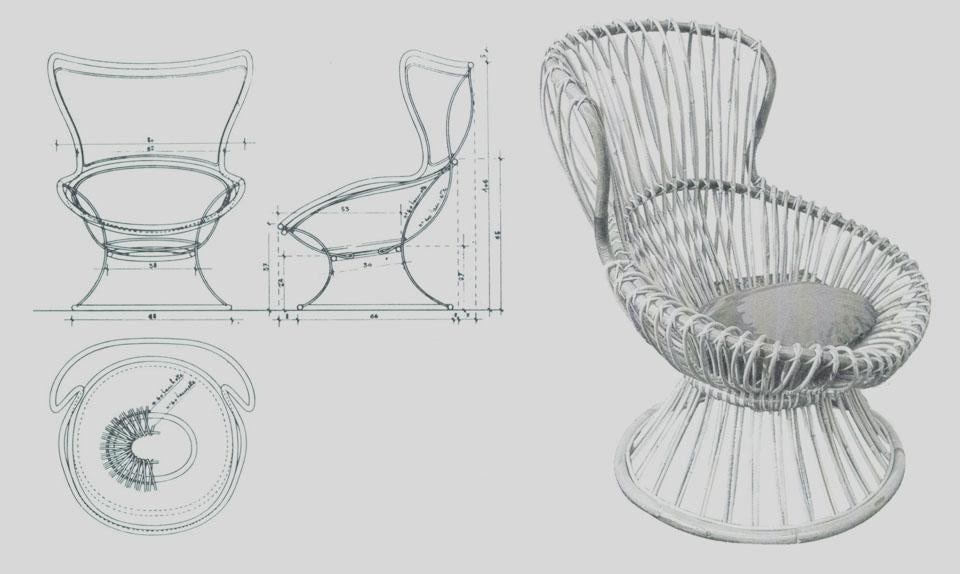

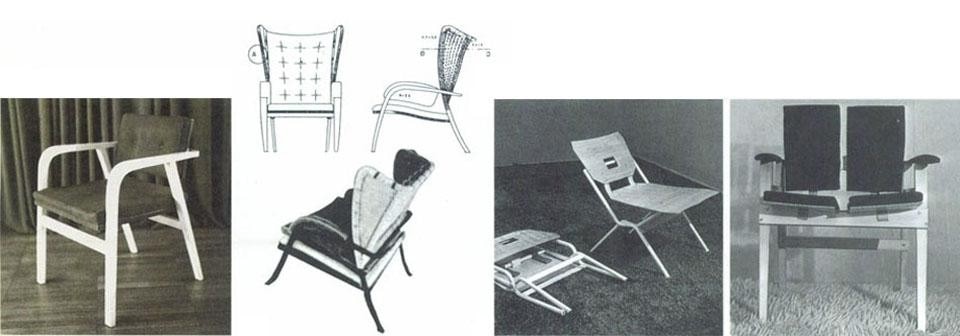

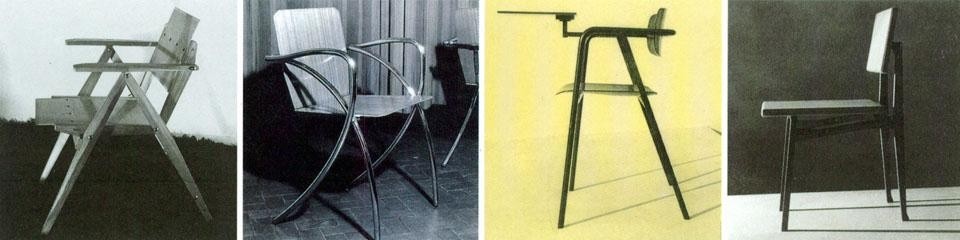

A meditated, critical review of the foundations of the modern movement, together with a careful balancing of innovation and tradition, are the key to the significance and importance of Albini's oeuvre. For it is characterized both by typological innovation and by a resumption of traditional methodologies and themes. As far as furniture design was concerned, he very soon established nearly all the types upon which he was to work for a lifetime. Albini's works can thus be appreciated only by singling out the basic types that generated them, which I would like to define as 'structural', The chairs, for example, are a constant variation on a single type already noticeable in the drawings for the Wohnbedarf competition of 1940.

Albini's postulate is, as always, very simple: the frame, stated in all its lean essentiallty, where the section of the material used is reduced to the utmost, bears the backrest and seat which rest on or are hinged to it at only one point.

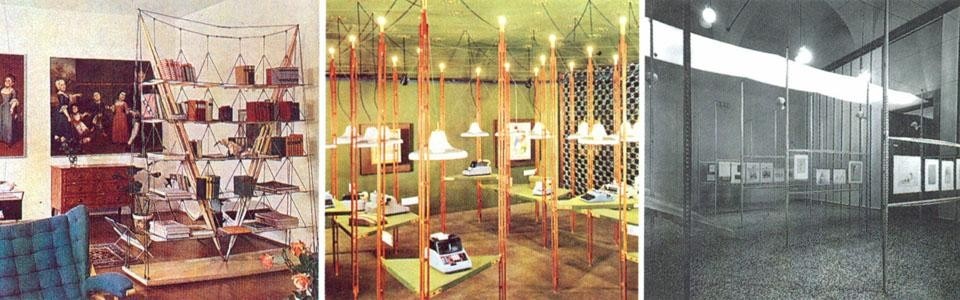

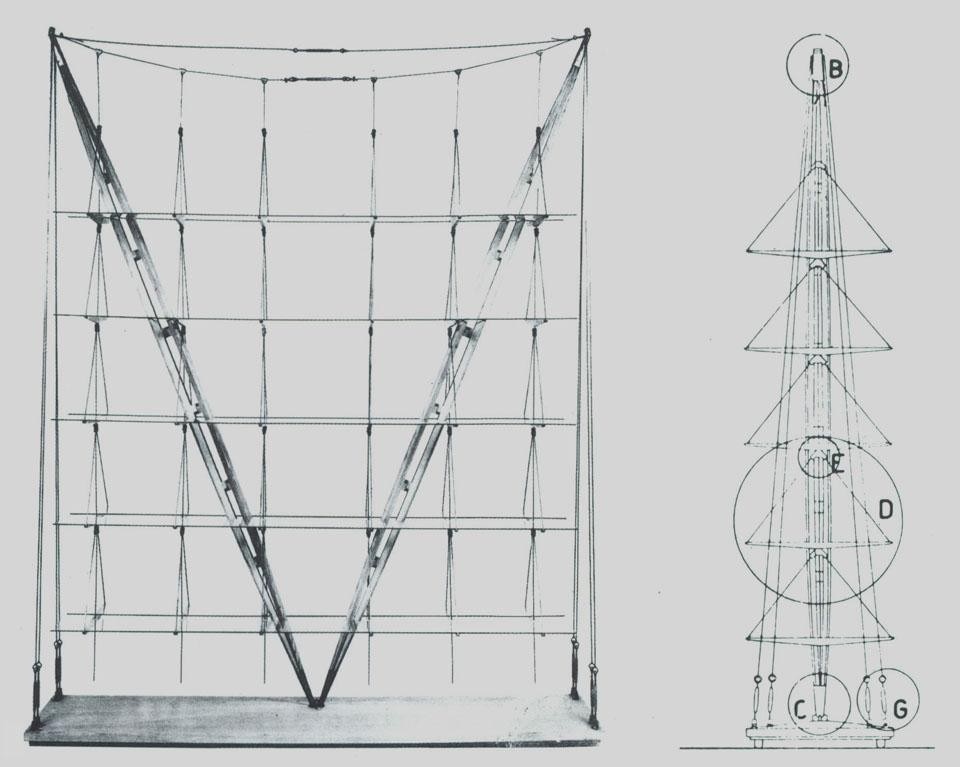

In some measure, this third group actually stems, conceptually and spatially, from the fourth type with we are concerned here: the upright standardo A simple vertical rod composed a rigorously modular three-dimensional grid with horizontal display units, in the Aerodynamics for the 15th Milan Fair in 1914, the interior of the INA pavilion at the Levante Fair at Bari in 1935. And in the exhibition of Antique Jewelry at the 6th Milan Triennale in '36, they already a sumed the more customary features of Albini's idiom, with the addition of horizontal rods to bear a suite of lamps, and so on gradually up to the "Veliero" bookcase for Albini's own apartment, a simplification of his design philosophy, an object in which we again find the constructivist roots of his earlier, architectural work. The two uprights are correlated by a complex tensostructure. From this are suspended the elements which in their tum hold up the glass shelves. The appearance is almost one of emptiness, reduced to four slender curved bars, juxtaposed and jointed to form a lighter-than-air 'casting'.