by Andrea Daniele Signorelli

“Our concern was that we had hired ten thousand people to build a smart timer,” a former Amazon executive told the Wall Street Journal last year. A statement that neatly sums up what, for many years, was Alexa’s main problem.

Since its launch in 2014, Amazon has always envisioned its digital assistant—integrated into the Echo line of smart speakers—as an intelligent “home hub,” capable of managing home automation (from smart bulbs and blinds to washing machines), helping us gather information, organize the family schedule, and assist in cooking and shopping.

Yet, even in 2022, usage data in Italy painted a very different picture: users had asked Alexa to set 800 million timers and alarms, requested weather forecasts 135 million times, and used their smart assistant for reminders and playing music.

These numbers confirmed regular usage of Alexa but mainly highlighted its limited and trivial use. How could this be? We had been promised a “smart hub” that would eventually know us so well it could anticipate our needs, yet we ended up with a device for setting a pasta timer and shouting music commands at it.

What went wrong? Why has the very symbol of the digital assistant revolution failed to deliver on its promises, despite more than 500 million devices with Alexa being sold?

In recent years, Amazon press releases have stopped highlighting the ways people were using Alexa—a possible sign that the company founded by Jeff Bezos realized that “setting hundreds of millions of timers” wasn’t something worth promoting. Another set of figures likely unwelcome to Amazon concerned the losses accumulated in this sector: between 2017 and 2021, the Alexa and smart speaker division reportedly lost over $25 billion.

Meanwhile, many other devices that were supposed to come to life through Alexa were abandoned or never materialized. The most striking example is Astro: the robot butler whose development cost $1 billion and sold for $2,400, but was permanently discontinued last year.

View gallery

View gallery

Alexa’s difficulties were highlighted during the wave of layoffs between 2022 and 2023 that hit the tech sector: according to the New York Times, the Alexa division was the main target of the 18,000 layoffs at Amazon.

What went wrong? Why has the very symbol of the digital assistant revolution failed to deliver on its promises, despite more than 500 million devices with Alexa being sold?

The advertisement of the first Amazon Echo put on the market (2016)

The limits of smart speakers

First of all, it should be noted that Alexa was not the only digital assistant to struggle. The same happened with Google Assistant and its Home line (launched in 2016), as well as Apple’s HomePod devices (launched in 2018 and powered by Siri). Making the situation even more complex—but also, as we’ll see, providing a possible solution to Alexa’s existential dilemmas—is the rise of large language models and “agentic AI,” which promise to succeed where smart speakers failed.

More than ten years have passed since Alexa was first introduced, which in Jeff Bezos’ vision was to eventually become ‘like the Star Trek computer.’ This sci-fi vision has yet to materialize, but now the prospect of an invisible computer that performs tasks on our behalf is coming ever closer.

This is all the more true considering that - by the admission of Amazon executives themselves - people have continued to shop on the e-commerce founded by Jeff Bezos using the app on their phones or computers, while the use of Alexa for shopping has remained marginal. This is far from a minor problem, since the main reason our homes have been invaded by Echo devices (sold at virtually zero margins) was precisely to incentivize shopping on Amazon through Alexa, ordering what we need by voice.

And here comes the second critical issue: voice. As Dustin Coates, author of Voice Applications for Alexa and Google Assistant, notes, “It’s too complicated to use a voice interface for more than a handful of tasks. The reason is also the difficulty in discovering new available functions. With an app or a webpage, all the things you can do are easily shown to you.”

In other words, a voice interface lacks “discoverability,” forcing users to experiment and make mistakes too frequently for a device meant for everyday home use.

There are also other problematic aspects. For music, any Alexa user knows how cumbersome it can be to ask it to play a song: it may misinterpret pronunciation, play a cover instead of the original, and overall make the process far more complicated than using Spotify or Amazon Music.

The evolution of Alexa

How can the various problems Alexa has faced over time be solved? “Alexa is about to get much smarter,” Jeff Bezos explained in a podcast interview in December 2023. And, ideally, more intuitive, useful, and easy to use. Less than a year and a half later, in March of this year, Alexa Plus was introduced, with gradual rollout (reaching “a few million users”) limited to the United States.

Compared to previous versions, this represents a qualitative leap: classic Alexa, Siri, or Google Assistant are “command-and-control systems.” They can understand a finite list of questions and requests, like “What’s the weather in Milan?” or “Turn on the bedroom light.” If a user asks something outside their programmed capabilities, the bot simply responds that it cannot help.

Alexa Plus, however, leverages large language models (specifically Amazon’s Nova and Anthropic’s Claude): systems trained on enormous amounts of text data to recognize, understand, and respond to virtually any input. It is the same technology used by ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini (which is also being integrated into its Home devices).

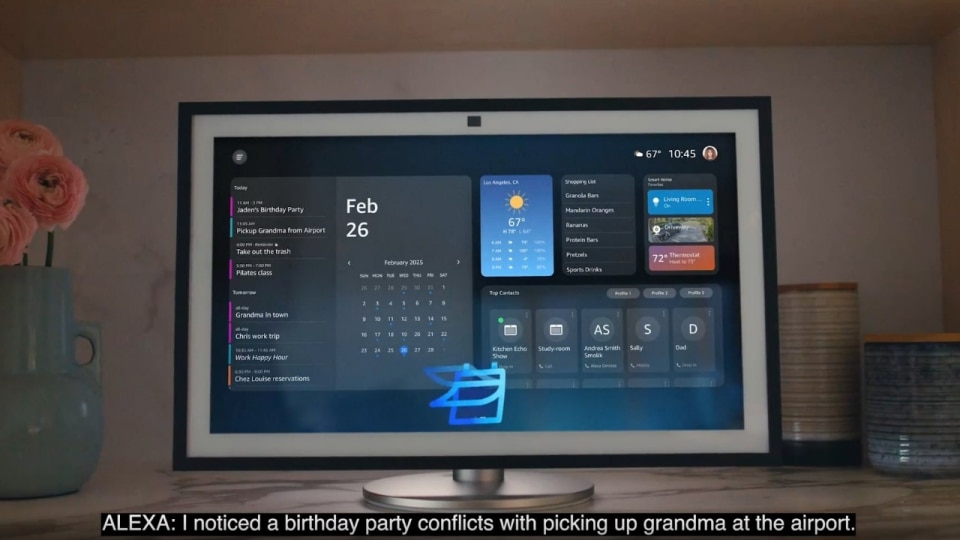

Unlike the past, when hardware multiplied while Alexa made little progress, Amazon now appears to have shifted strategy, focusing resources on Alexa’s capabilities. According to Panos Panay, the division head, “Alexa has been redesigned from scratch” and is now conversational (no longer requiring activation by name each time), proactive, and equipped with “reasoning” abilities (inference) typical of generative AI systems.

The trend is clear: two once very different products—generative AI and digital assistants—are converging, aiming to fulfill the same role: helping us manage our lives.

To illustrate the change, consider the timer example: previously, before putting a chicken in the oven, we had to tell Alexa the cooking time. Now, we can simply explain what we are cooking, and Alexa suggests the appropriate duration.

Similarly, Alexa can tell us how to use leftovers in a recipe or, outside the kitchen, help manage a shared calendar, suggest what to wear based on the weather, and ultimately act as a digital assistant on par with ChatGPT or Gemini—designed primarily for voice interaction (the website and app have also been redesigned and enhanced).

Another major difference, reflecting a shift in business models, is that Alexa Plus costs $20 per month (unless you have a Prime subscription). It is no longer just a “proxy” to drive Amazon purchases, but a paid service in its own right.

Will this be enough to make Alexa and the Echo lineup a profitable business? And, crucially, will it be sufficient to fend off competition from AI agents, which promise to perform more tasks for us (reservations, shopping, calendar management, vacation planning, etc.), primarily via keyboard interaction?

As recently as 2023, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said that “voice assistants are as dumb as rocks” compared to generative AI systems. Now, the situation has radically changed: the two products—both based on large language models—have become comparable. Alexa Plus is effectively an AI agent that can, for example, book a restaurant table for us (integrating OpenTable), call a taxi (via Uber), buy concert tickets (via Ticketmaster), and perform other tasks that will be gradually integrated.

Although there are still limitations (such as “hallucinations,” when the machine misinterprets or responds incorrectly), the trend is clear: two once very different products—generative AI and digital assistants—are converging, aiming to fulfill the same role: helping us manage our lives.

This is further demonstrated by news from mid-September, reporting that OpenAI (maker of ChatGPT) signed an agreement with Luxshare to produce what, according to The Information, would be a smart speaker. Development is expected to be led by former Apple designer Tang Tan, whose studio, founded with Apple’s John Ive, was acquired by OpenAI last May for $6.5 billion.

In short, as Alexa becomes more like ChatGPT, ChatGPT now wants its own version of Amazon Echo. More than ten years have passed since Alexa was first introduced, which in Jeff Bezos’ vision was to eventually become “like the Star Trek computer.” This sci-fi vision has yet to materialize, but now—with the push from generative AI—the prospect of an invisible computer that responds to our voice commands and performs tasks on our behalf is coming ever closer.