By Nicolas Vamvouklis

Performance art is often treated like a rumor: people say it matters, but when pressed they reach for anecdotes, not reasons. If your reference points are still the 1970s—endurance in a white cube, the solitary artist against the wall—it can feel remote from the practical concerns of institutions. Yet over the past decade performance has migrated from the margins to the center of museum life. Not because curators became nostalgic, but because live time addresses contemporary needs: how to create attention, how to host publics, and how to work with histories that are still unfolding.

Start with attention. Paintings can be skimmed; buildings can be photographed and left. A performance is an appointment. It asks you to arrive at a specific hour, bring your body and your patience, and accept that the work happens in relation to you. That modest demand quietly rewires the institution around it. Ticketing shifts toward timed entry. The foyer becomes a threshold rather than a holding pen. Guards become mediators who can answer questions and calibrate the room. Documentation stops pretending to replace the event and becomes a promise that the encounter will return. Performance reorganizes the museum at the level where visitors actually feel it.

Live time addresses contemporary needs: how to create attention, how to host publics, and how to work with histories that are still unfolding

This is not only cultural; it is architectural. Most museums were built to shelter objects, not live practices. Still, small design moves go a long way: resilient floors, clear sightlines, dimmable rigs, quiet HVAC, access to water, and storage for props. The goal is not to smuggle a theater into a gallery but to let exhibitions host choreographies of reception. Think flexible seating that can be reconfigured without a forklift; power outlets where artists actually need them; and a loading-dock schedule that respects rehearsal time rather than treating it as an afterthought. When these basics are in place, the building itself starts to collaborate.

Hospitality ties it all together. Performance forces institutions to clarify whom they serve and how. Serious programs treat audiences as participants with varied needs. Basics sit alongside subtler questions of address: in what language is the preface written, and who understands it? Does the floor plan invite people who use mobility aids to sit where they can actually see? Are the acoustics tuned for a voice, not just a projector? These are not extras; they are the ethics of a live encounter made legible.

Conservation is the familiar anxiety. How can a museum collect something that vanishes? The honest answer is that it collects agreements rather than moments. Scores, protocols, training videos, oral histories, casting notes, and rights to re-perform are the toolkits that let a piece persist without becoming a relic. This insight is not new (Fluxus boxes and instruction works taught it decades ago), but methods have matured. Conservation teams now speak of “recalibration” after acquisition: learning how a work adapts to new rooms, new casts, new regulations, and new publics while remaining itself. The conservator’s craft shifts from stabilizing matter to stewarding conditions.

Economics matter, too. Performance is sometimes caricatured as cheaper because there is “nothing to buy.” In reality, the budget tilts toward time: rehearsals, fair pay, producers, riggers, access consultants, and understudies. The cost profile is different from painting but no less real. What institutions gain is different, too: agility, civic relevance, and a public that returns because they know something will happen. A live program becomes the pulse of a building. It also reshapes the calendar. Exhibitions are no longer the only tempo; sequences of events set a rhythm that can sustain attention over months.

The goal is not to smuggle a theater into a gallery but to let exhibitions host choreographies of reception.

Critics say performance disappears. I’d argue it teaches how to remain. The residue of a strong work is not a selfie; it is a new behavior. After an interactive piece that channeled anger into technique, I noticed my breath for days. After a guided walk that repositioned whose stories were legible inside galleries, I read labels with a different skepticism. Performance is a school for attention, and institutions that host it become schools, too. They train publics to arrive, to listen, and to leave differently.

Mediation, what happens between a work and its audience, becomes visible and precise. Programs that succeed are clear without being literal: a one-paragraph brief at the door; a floor team able to answer questions without policing tone; documentation that respects liveness without pretending to replace it. The worst approach hides performance behind insider jargon; the best treats visitors as intelligent strangers. Language matters on the website, in the caption, and in the first sentence spoken in the room, because it establishes what kind of attention is being asked for.

Collection raises another live question. What does it mean for a performance to enter a museum’s holdings? The Fluxus example is instructive: museums don’t only keep objects; they keep possibilities. An instruction piece can be enacted in more than one way and still be the work. That principle now informs choreographic acquisitions, disability-led projects, and time-based commissions. Acquisition committees learn to read contracts as carefully as canvases: who has the right to re-perform, how are casts chosen, what training is required, which parts are variable, and which are non-negotiable? The ledger changes, but the responsibility remains: to preserve the integrity of the work while allowing it to live.

Equity is inseparable from all of this. Whose bodies are centered? Who gets to speak, and in what tongue? Which publics feel welcome, and which feel watched? Performance can reproduce hierarchies unless institutions build trust and share resources. That means commissioning artists early enough to shape the space, not parachuting them into inhospitable rooms. It means inviting critique during planning, not after the press release. And it means acknowledging that a museum is not neutral ground; it is a civic actor with obligations.

Performance is an infrastructure for attention that museums can learn, maintain, and share.

Digital media folds in naturally. Social platforms are not the enemy of performance; they are part of its ecosystem. An Instagram story can be a sketchbook, a rehearsal log, or a bridge to audiences who cannot enter a museum. The distinction is between documentation that flattens and documentation that invites. Short clips that teach are apertures. They don’t replace the live encounter; they extend it, giving people a way to carry the work home and share its methods rather than its image alone.

If all this sounds idealistic, consider how simple the first steps can be. To move from “we host performance occasionally” to “this is part of who we are,” an institution can take five actions. First, name a producer with decision power; live programs die in committee. Second, equip one gallery as a ready room so every commission doesn’t start from zero. Third, write acquisition templates for scores and training so collecting a performance isn’t a legal improvisation. Fourth, invest in mediation: pay artists and educators to co-design how the public meets the work. Fifth, measure success beyond footfall: track return visits, dwell time, and the program’s ability to draw new communities into the building.

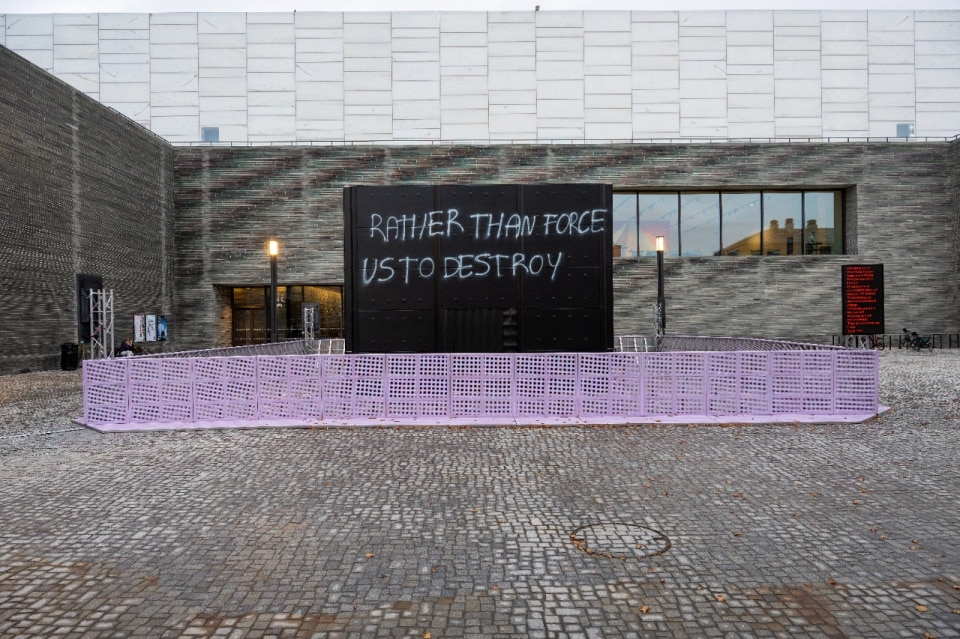

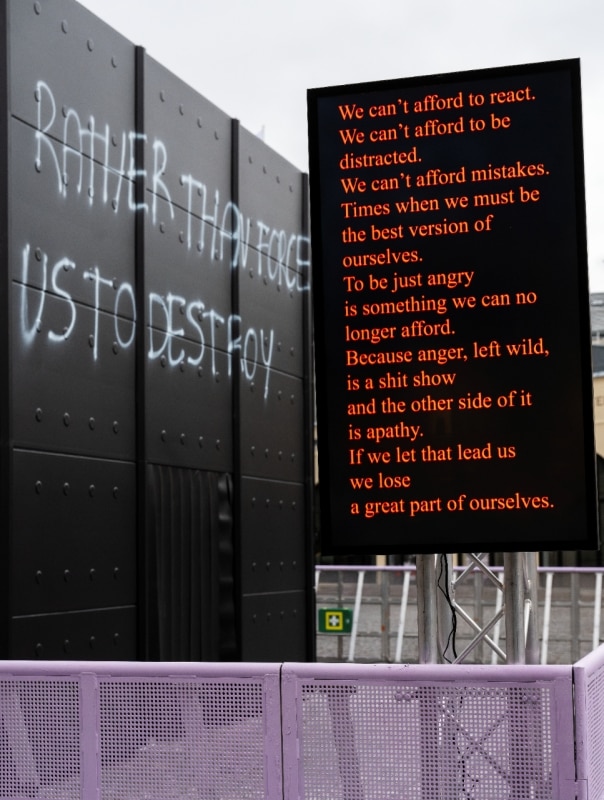

Everything sketched here was sharpened by the weekend event“ In the Moment” at the National Museum in Oslo, where a concert, an interactive installation, a guided walk, and a day of talks sat side by side. This is not a review, but a reflection on performance’s place in institutions today, prompted by that encounter. What became clear is simple: performance helps institutions rehearse the kind of public they want to be—attentive, porous, fair—and helps audiences practice presence at a human scale.

So, is performance still relevant? The better question is: what else teaches us to gather, listen, and change with such modest means? Performance is an infrastructure for attention that museums can learn, maintain, and share. Start with one room, one producer, one score; add hospitality and time; repeat. The rest follows. And if you’re still unsure, go with someone you care about. Notice how you both walk out: slower, maybe, or louder, or newly curious about the space between you. That change is the work, and it is very much of this moment, right here, right now.

The images were taken during the event "In the Moment. Performance at the National Museum"(Oct. 25-26, 2025) at Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo, which featured performances by Meredith Monk, Elina Waage Mikalsen & Jassem el Hindi and SAGG Napoli. Courtesy Nasjonalmuseet/Frode Larsen.