“Peace be with you all! Dear brothers and sisters, these are the first words spoken by the risen Christ, the Good Shepherd who laid down His life for God’s flock. I would like this greeting of peace to resound in your hearts, in your families, among all people, wherever they may be, in every nation and throughout the world. Peace be with you!”

The solemn debut of the new pope, Leo XIV, evokes a deep connection with the long and vulnerable line of his namesake predecessors. Leading figures, these popes embodied, in their own way, the yearning for peace and the defense of the Church—qualities that resonate powerfully in Leo XIV’s inaugural words.

Herrera enhances the inner drama of a man entrusted with a transcendent mission. A drama that reveals itself in the twisting of the body [...] and in the drapery of the vestments, stirred by a wind—perhaps a divine one.

A striking example of this authority is represented by Saint Leo the Great (Pope Leo I). In the painting by Francisco Herrera the Younger, housed in the Prado Museum, Leo the Great stands out with a complete absence of superficiality and uncertainty.

The painting captures the rigid firmness of his faith, the awareness of being the servus servorum Dei, and an authority and dignity that inspire reverence. Far from the serene composure of an icon, the painting bursts into the visual space with an almost feverish vitality, a hallmark of the Andalusian master’s unmistakable style. There is no trace of the hieratic monumentality of a cold, definitive classicism. On the contrary, the viewer is immediately drawn in by a compositional dynamism that transcends the stillness of the canvas. The figure of the pope is translated and interpreted through tense brushstrokes and a vivid chromatic palette.

Herrera enhances the inner drama of a man entrusted with a transcendent mission. A drama that reveals itself in the twisting of the body, in the intense gaze that peers into the invisible, and in the drapery of the vestments, rippling as if stirred by a wind—perhaps a divine one.

Educated in a cultural environment dominated by an exuberant and theatrical Baroque, Herrera the Younger does not abandon his stylistic heritage. However, his interpretation of the sacred is charged with a more intimate emotional vibration—almost a spiritual confession made public through the powerful language of color and line. This is not merely a hagiographic illustration. While respecting the canonical narrative, the artist bends it to his own expressive urgency. Light, a crucial element in his painting, is not a simple scenic device, but becomes a protagonist, shaping forms with sudden flashes and creating areas of shadow that heighten the sense of mystery and transcendence.

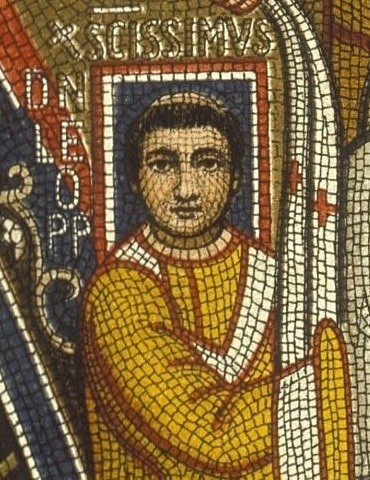

Turning our gaze to Leo III, his effigies convey the majesty of a transitional era. An influential pope, he sealed a new chapter in European history through the coronation of Charlemagne. In his eyes, we can read the responsibility to guide the Church in a changing world, weaving bonds between the sacred and the temporal. In this sense, Leo III reveals a register that is more political than religious.

It was with the rise of Leo X to the papal throne that a new and significant decorative phase began in the Vatican Rooms, entrusted to the mastery of Raphael. That Medici, a man of cultured spirit and sensitive to the arts, sought to leave a celebratory mark on his pontificate through the pictorial cycle of the third room. It is said that his inspiration emerged from the evocative scene of the encounter between Leo the Great and Attila in the Room of Heliodorus. In this earlier work, Leo III did not hesitate to replace the effigy of his predecessor, Julius II, with his own, in a subtle act of self-representation. Therefore, the choice fell on celebrating popes who shared his name, Leo III and Leo IV, whose deeds, passed down through the Liber Pontificalis, were suitable to veiled allusions to the current pontificate, its initiatives, and its role in Christendom.

The first result of this commission was The Fire in the Borgo, an episode that ended up designating the entire room. In this work, the direct participation of the master from Urbino is still palpable. However, the succession of major undertakings commissioned by the pope—such as the monumental construction of St. Peter’s Basilica and the creation of the fine tapestries for the Sistine Chapel—required an increasingly significant contribution from Raphael’s workshop, a forge of talents such as Giulio Romano, Giovan Francesco Penni, and Giovanni da Udine.

The analysis of the Coronation of Charlemagne, while attesting to Raphael’s design through several preparatory drawings, reveals a level of execution that suggests a broad involvement of his pupils, particularly Penni, Raffaellino del Colle, and Giulio Romano.

The historical episode of Charlemagne’s coronation by Leo III—an event that culminated on Christmas night in the year 800 at St. Peter’s Basilica—is laden in its pictorial representation with a subtle political significance. A plausible interpretative key lies in the allusion to the Concordat signed in Bologna in 1515 between the Holy See and the Kingdom of France. The pope’s face depicts the features of Leo X, while those of the emperor recall Francis I, the French sovereign at the time the fresco was created.

The pictorial composition unfolds along a diagonal axis that draws the viewer’s gaze, guiding it through the various spatial planes toward the focal point of the scene: the solemn act of coronation. This takes place beneath an imposing papal canopy, whose richly decorated drapery and the presence of the symbolic keys of St. Peter radiate an aura of sacred authority and festive celebration.

Surrounding this epicenter is a select gathering of high-ranking ecclesiastical figures—cardinals and bishops in their liturgical vestments—and military dignitaries clad in armor and bearing their insignia. Together, they form a human frame of extraordinary significance, a kind of living theater that amplifies the solemnity of the act. On the left side of the scene, the altar—the focal point of Christian liturgy—stands as a silent witness to the historical event. Conversely, in the foreground, a group of attendants is captured in the act of arranging precious objects of goldsmithing: exquisitely crafted silver and gold vessels placed beside a table with gilded supports, all set upon a sacred table.

This attention to lavish detail and the meticulous arrangement of ritual objects unmistakably evokes the pomp and magnificence of the triumphal processions that once celebrated the power of imperial Rome, suggesting a subtle parallel between the grandeur of the past and the solemnity of the contemporary papacy. Giorgio Vasari recognized in the kneeling page beside the imperial figure—holding the royal crown destined to be replaced by the imperial one at the hands of the pope—the features of the young Ippolito de’ Medici. The architectural backdrop of the scene, consistent with the other Rooms, seems to echo the state of construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica.

In the narrow space above the doorway, Raphael’s ingenuity found expression in the creation of a finely inlaid choir loft, from which young choristers lean forward in quiet observation of the event, one of them holding a musical score in his hands. Leo X’s passion for the art of music led him to establish a renowned choir for liturgical celebrations in the Sistine Chapel—a detail that further illuminates the cultural context and artistic inclinations of the patron behind this extraordinary commission.

“There are three things that are stately in their stride, | four that move with stately bearing: | a lion, mighty among beasts, | who retreats before nothing; | a strutting rooster, a he-goat, | and a king secure against revolt.” (Book of Proverbs)

Opening image: Raffaello Sanzio and others, Incendio di Borgo (The Fire in the Borgo), 1514, Stanza dell'Incendio di Borgo, Vatican Museums, Vatican City. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons