“And as far as good style in painting is concerned, we are primarily indebted to Masaccio, who, before any other, painted all figures with their feet placed firmly upon the ground, and thus removed that awkwardness of making figures on tiptoe, universally used by all painters up to that time. Moreover, he gave so much vividness and so much relief to his paintings, that he certainly deserves no less recognition than if he had been the inventor of the art. To tell the truth, the works created before Masaccio can be described merely as paintings, while his creations, compared to those executed by others are lifelike, true, and natural.”

It is Masaccio, Florentine master, the godfather of the Italian Renaissance. The Crucifixion comes to Milan from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples. From Feb. 22 to May 7, 2023, the Diocesan Museum “Carlo Maria Martini” exhibits a work of extraordinary beauty, of powerful magnificence, one of the greatest masterpieces of Italian art.

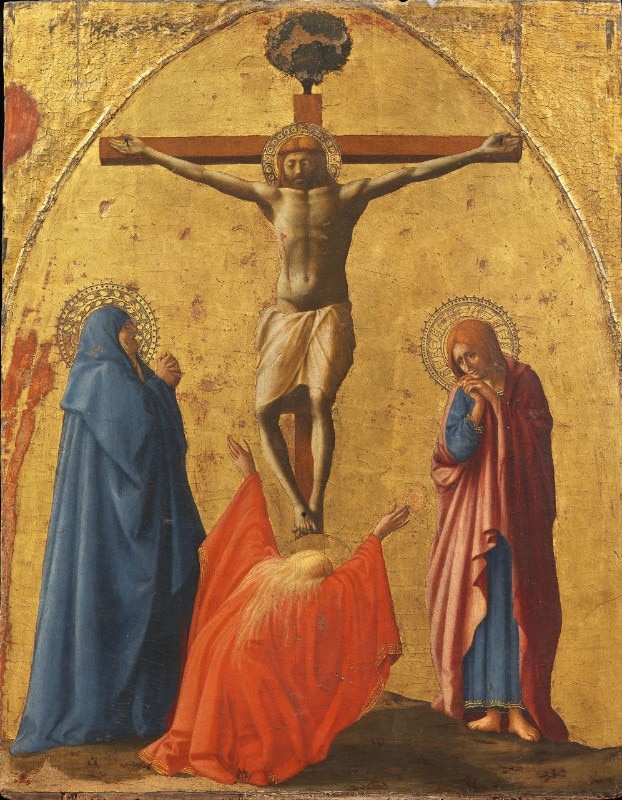

A simple space, a symmetrically studied gold background.

Four figures: Christ, painted frontally. The Madonna on the left. His beloved disciple, St. John, on the right. And Mary Magdalene, kneeling with her back to her. Starting right from Christ, a bit disheveled, almost ungrammatical, almost unrealistic. His head recessed into his chest and his shoulders too high compared to reality.

It was intentional. In fact, the artist’s architectural and pictorial wisdom emerges from the realization of Christ on the cross. Since the Crucifixion was placed at a height of about five meters, the figure of Christ needed a different perspective, more compact but less real in form. Hence the viewer could have a more complete, perspective view. An extraordinary trick.

The mother, the Madonna – made majestic by the voluminous draperies – is depicted in a moment of absolute anguish. Her face is in despair, afflicted with tears. Her hands are so tightly clasped together as if to hurt. She seems to want to imprison with her hands that pain, crazy and unnatural as the death of a child, her child, the child of God.

St. John is gentler, less fierce the pain on his face, too young for such great pain.

Last but not least: Mary Magdalene. The culmination of the painting. A burst of pain. Here she is, arms raised, facing upward, so disheveled and desperate. Here she is, emotion in a work of art. From her back, unconcerned about the faithful watching her, she is totally living in the moment, along with her humanity. Her distinctive long hair highlights even more the color of her robes, drawing attention away from everything else. There is only her and her cries of pain, only her and her hidden weeping, only her at the feet of Christ.

The dismembered and partly lost Pisa Altarpiece is exhibited at the Diocesan Museum in a theatrical setting that leaves visitors breathless, but above all leaves room for the work. Curated by architects Alessandro Colombo and Paola Garbuglio, the setting up includes a video installation that reconstructs in life size the layout of the polyptych.

Thanks to Vasari’s description of the panels, eleven of them were traced in various museums around the world. Such as the National Gallery in London, where the central panel the Madonna Enthroned with Child and Angels is kept, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the National Museum in Pisa, or the Getty Museum in Malibu. Other panels are still missing.

The exhibition is curated by Nadia Righi – director of the Diocesan Museum of Milan – and Alessandra Rullo – curator of the 13th, 14th and 15th century paintings and sculptures department of the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. With the patronage of the City of Milan, it is dedicated to Alberto Crespi, who recently passed away. He was a refined collector who donated his important collection of forty-one works on a gold background to the Diocesan Museum in 1999.

A work that anticipates contemporary times, approaching human pain, which we could somehow interpret and transfer to the present day as a social image. Private and real. We see those atrocious scenes full of dismay every day: earthquakes, wars, boats that hardly arrive in safe harbors, death and pain. An idea, a project that far anticipates a contemporaneity that commodifies pain. However, unlike today, Masaccio glorifies and makes it pure and gentle in its divine message.