Centuries ago, there was a certain kind of painting that was neglected, not to say forgotten, and never made famous. Even today, we can’t manage to introduce its subjects into our daily life. The current events seem to confirm it, and the protests in America after the death of African American George Floyd have once again brought to light the never-ending question. Artistic orientations tend to follow the trends of the time, and the new choices taken by the artist artists are supported with polemical passion or observed with respect, sometimes even with ferocious irritation or sympathetic disdain.

Painters started to represent dark-skinned people immediately after America was discovered. Renaissance painters often used to include slaves in their paintings in order to hint at the alchemical process of the nigredo, or blackness. However, it was immediately after the French Revolution, when slavery was abolished, and later re-established by Napoleon, that dark-skinned men and women became the protagonists of the paintings of artists, especially French ones.

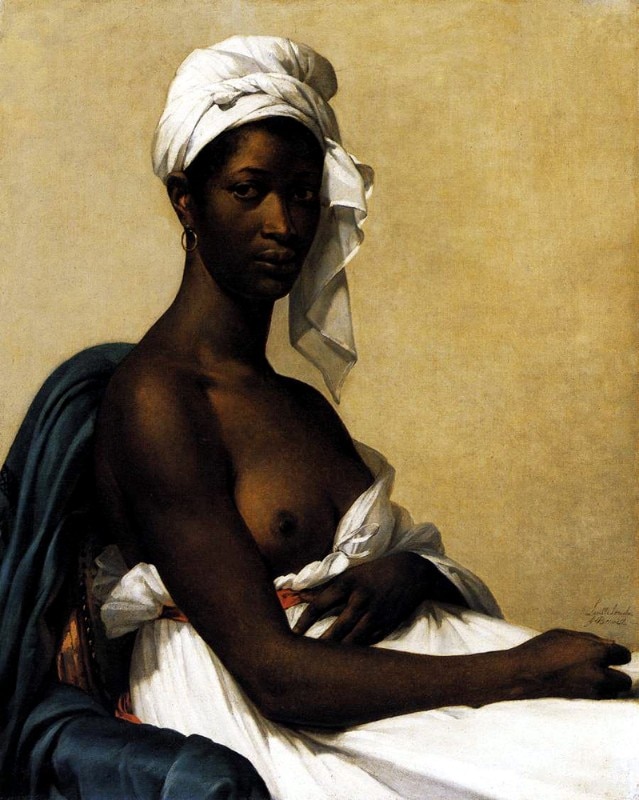

At the beginning of the 19th century, Marie-Guillaumine Benoist painted the Portrait of Madeleine, a beautiful black-skinned Raphaelite La Fornarina. The white headwrap and the garment barely covering her breast emphasize and enhance the woman’s features and color. She is sitting on an armchair with a beautiful blue trim on it, as if she were a Madonna who has just abandoned her role. It was Nietzsche who first hypothesized that, in ancient Greece, blue was avoided because it dehumanized more than any other colour. Moreover, blue has always been attributed to the Virgin Mary, in order not to make her look earthly, or real. A strong and precious colour, the most prestigious, a colour that is above all expensive because it is obtained through a difficult and time-consuming process.

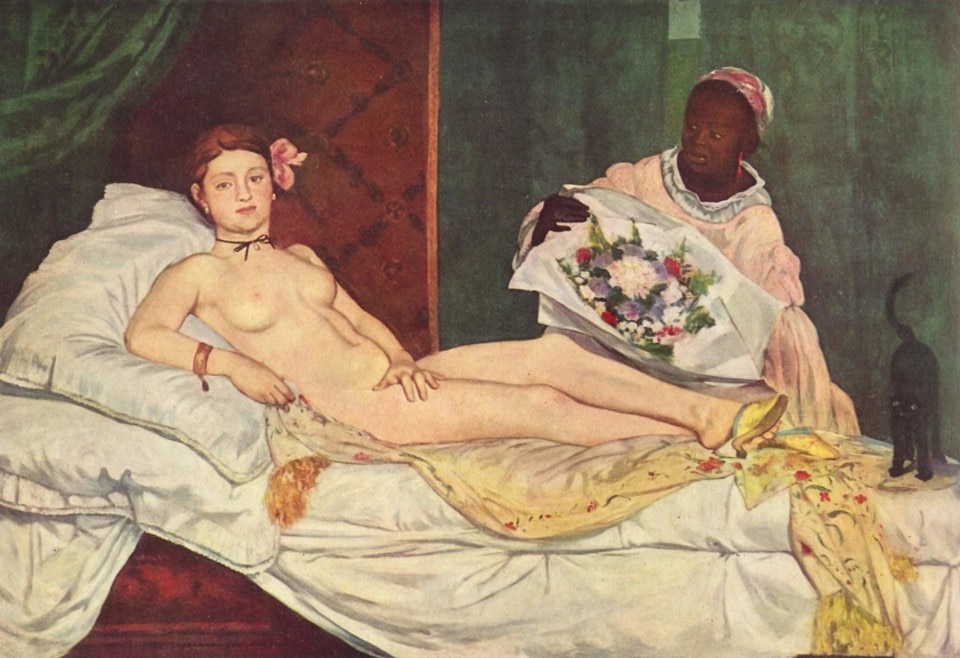

Dark-skinned men and women can be found on artists’ canvases and among the pages of books. Let us not forget the figure of Jeanne Duval, Charles Baudelaire’s lover. It was difficult to accept their characteristics, their faces, their bodies, their clothes, but Edouard Manet decided to do it when portraying his Olympia, lying down just like a goddess, accompanied by a powerful figure behind her: the black servant. She is handing flowers to the prostitute with reverence, as a protest in a typical bourgeois setting, where the so called "black maidservants” only worked for prostitutes, since white women refused to work for such disreputable women.

At the foot of the bed we find a black cat, a traditional symbol of lust and betrayal, contrary to the usual dog, just like in Titian’s Venus, which is a symbol of fidelity. The animal gets frightened at the sight of the client of the prostitute entering the room, and this makes its fur stand up. This painting, which was a modern interpretation of a Renaissance masterpiece, was harshly criticized. Everything was in the right place, but that everything was the opposite of everything. It was a scandal.

Stendhal said that painting is nothing but a construction in ethics.

These ideas and this desire to experience some kind of exotic charm, and to transfer it on canvas, wasn’t abandoned in the following years. About 50 years later, Felix Vallotton portrayed Aicha, a symbol of the early 20th century, and this helped African Americans to find a home, especially in Paris, among the notes of jazz. He tried to forget everything he had seen and studied in museums and put into practice the advice he received from the paintings of the past, by creating a chronicle of contemporary reality. The artist thus created a work that represented a personal, strong, different beauty, with a different temperament, with an imperious need to recreate in that woman a vainer spectacle. His most typical colours are still there: the woman, perhaps embarrassed or hesitant about her pose, but proud of what she was and what she represented in those years, is wearing a bright green dress. Everything is perfectly balanced in an almost absent chromatic scale, but extremely seductive and vibrant. The green and red build the work in a chiastic figure that balances and envelops everything, and in the center, the silky, darker skin amazes the viewer: a foreign, almost impalpable charm.

An experience of a real, cultural observation based on an idea of evolution and change, of social inclusion that comes from a distant past and that doesn’t find fertile ground in everyone. Art should be a preliminary model thanks to which humans can discover how to order, analyze and, above all, reflect on their surroundings. It dictates the guidelines of a revolutionary social and aesthetic vision. But then, why have these subjects been abandoned by contemporary critics, exhibitions, books and the public? Abandoned, and disrespected. Even today.

Opening image: Felix Vallotton, Aicha, 1922