For a few weeks now, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the most famous art curator of our times, has been proposing a massive public art project to support artists after the COVID-19 pandemic. This would be similar in scale to the American New Deal, which was instituted immediately after the financial crisis of 1929. Let’s try to understand what this plan was about by briefly retracting its history.

Among the thousands of people that lost their jobs during the Great Depression, there were also hundreds of artists, writers, musicians, actors and dancers. This is why the New Deal, a complex series of economic and social reforms, also involved a project to support art and artists. It was the painter George Biddle who suggested to his friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt to include the work of artists within the Civil Works Administration (CWA, an employment program), but it was Eleanor Roosevelt, together with Harry Hopkins, his collaborator and head of the CWA, who convinced the president to do that. Between December 1933 and June 1934, after receiving funding from the Civil Works Administration, the Public Work of Art Project (PWAP), directed by Treasury Administrator Edward Bruce, which already supervised the acquisition of works of art by the state, was established. The aim of the project was to give work to artists through the creation of works intended to decorate public buildings and parks. About 3700 people were employed thanks to the PWAP, and created more or less 15,000 works of art. However, according to the book Art Since 1900: "In New York, those who were lucky enough to be employed by the PWAP, spent their time cleaning and fixing the statues and monuments of the city". Nevertheless, according to the words of L.Glenn Smith in 1984, the social effect seemed to have had positive implications, because “The artists who received jobs under the plan experienced a powerful emotional catharsis. The society from which they had so long felt alienated and which had driven some of the most talented Americans to Europe was finally according them recognition”.

The experience of the CWA and therefore also that of the PWAP ended in 1934, and, according to an article by Francis V. O’Connor published in 1969 in "The American Art Journal", two other similar projects were created: first, the Treasury Department established a Department of Painting and Sculpture with the aim of employing artists in the decoration of government buildings; then, in 1935, the Word Progress Administration (WPA, new name for the CWA) was established, for which Hopkins himself created projects dedicated to the arts, in particular writing (Federal Writer’s Project), theater (Federal Theater Project), music (Federal Music Project) and painting and sculpture with the Federal Art Project which continued until 1943.

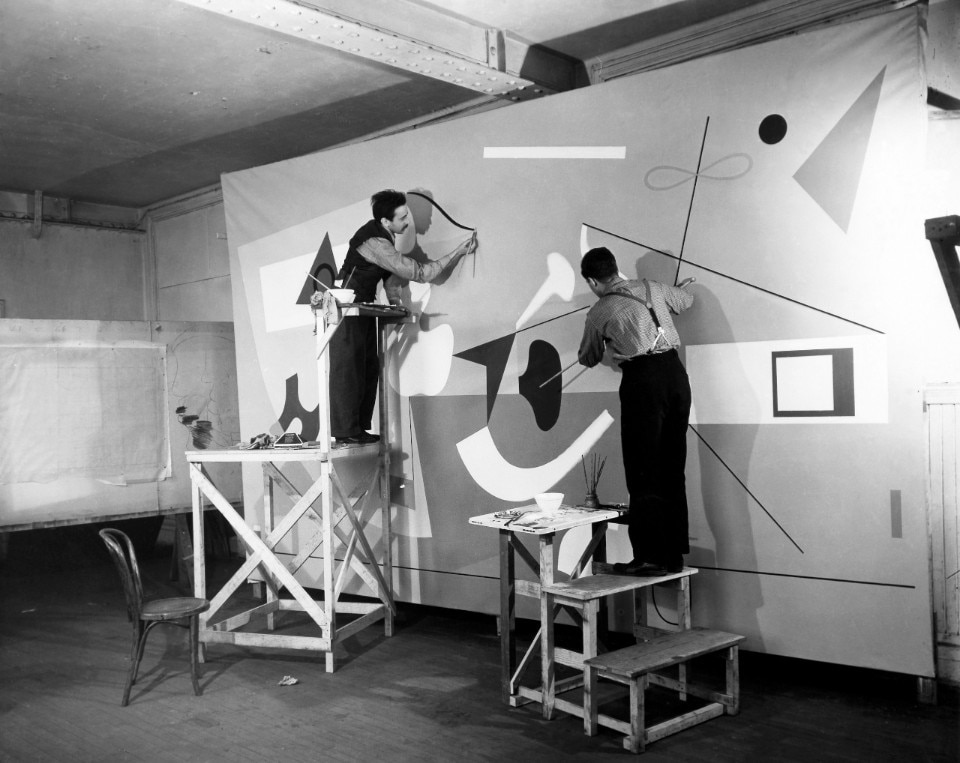

The Federal Art Project was directed by Holger Cahill (who had also previously served as acting director of the Museum of Modern Art) and was divided into two sectors: mural and easel painting. The artists were then classified and paid as "amateur, intermediate, advanced or professional".

Artists such as Jackson Pollock (it is known that his mosaic was rejected) and Mark Rothko, for easel painting, took part in the project, while Willem de Kooning, Ila Bolotowsky and Arshile Gorky worked for the division dedicated to murals, which were designed and conceived by one or two artists for a specific place and were then created by a group of painters. When in 1937 the government decided that the participating artists had to be of American nationality, Rothko, De Kooning and Gorky could no longer be included.

About 200,000 works were produced throughout the duration of the Federal Art Project and not all of them survived. This great production not only supported the artists and enhanced their work, but also gave the American population the opportunity to enjoy works of art that appeared in many public places frequented daily by citizens, such as post offices. In addition, according to Foster, Krauss, Bois and Buchloh, “the Federal Art Project had a surprising effect, that of making artists work together in completely new ways [...] Relieved of the obligation to do chores for a living, these full-time artists began to perceive themselves as a community”.

Finally, we must not forget that in 1936, thanks to the New Deal, also the Farm Security Administration (FSA) was established, with the aim of fighting the poverty that had gradually increased in rural areas. It was the FSA that hired photographers such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange to document the situation in the countryside.

The difficult moment that we are now experiencing forces us to reflect on the consequences of COVID-19 and isolation, which are expected to be economically devastating in every sector. The suggestion to take inspiration from the American experience of the 1930s, launched by Obrist, is interesting, but it is clear that it would not be enough, ninety years later, to repeat that very same model. Not only have the policies supporting the arts changed, just as the social recognition of the role of the artist has changed, but the languages and approaches adopted by artists are no longer the same today: even the visual arts no longer merely respond to rigid classifications, the possibilities have extended to a wide variety of expressive tools that, to name but a few, range from digital to relational practices.

Immagine di apertura: Coit Tower, San Francisco. Photo Another Believer.