An occasion like the Frieze Art Fair is not just an observatory of current aesthetic trends. It can direct attention to the varied relations contemporary art forges in culture and society. The body is the true focus of this edition of the fair. Struggling with its various definitions, the body’s presence clashes with a society that shuns physicality and contact. This theme keeps cropping up in a dense web of artistic offerings expressed through a broad range of media, including performance, which remains a fundamental instrument for the expressive urgency associated with the dynamics of identity.

The Superflex collective uses the Space of the Turbine Hall to create an installation for us not just to look at but traverse with our bodies. At the entrance a giant pendulum oscillates above a floor glowing with a thousand colours. Then, across the bridge in the middle that bounds the architectural space, it gives way to a spidery structure supporting a number of playground swings immersed in artificial light emerging from the darkness. Visitors’ immediate physical reaction is to indulge in the game, using their gravitational weight to move the swings, mimicking the movement of the pendulum, which is simply the constant and inevitable passing of time. Through a physical association, the child's thoughtless game takes on new and sometimes disquieting overtones, prompting the viewers to get involved in the temporal mechanism, which is irresistible.

Not far from Tate Modern, the artist Eddie Peake activates the dimension of a square in the forecourt of the White Cube in Bermondsey. Peake orchestrates the choreography of two female bodies and two male, set in the space of a big empty rectangle with the public all around. The artist is present on the “stage-square”, sampling sounds and words at the console, creating another language superimposed on the movements of the performers, who occasionally mime sexually allusive actions or traverse the space with amplified gestures.

As happens every year, the David Roberts Art Foundation in Camden celebrates performance with a special evening. This time it is a “Grand Ball” at the celebrated KOKO, a concert venue with central stage and a giant mirror ball suspended from the ceiling. A crowd of viewers spread over the four levels between the pit and boxes in the middle and side. Over 80 performers alternate sounds, songs, activities, dances, costumes, lighting and much else. It is impossible to describe what's going on everywhere or list precisely all the individual identities, merged into a single expanded body. It is a kind of contemporary carnivalesque inversion that overwhelms the stage of the old theatre with the energy radiating from the performance.

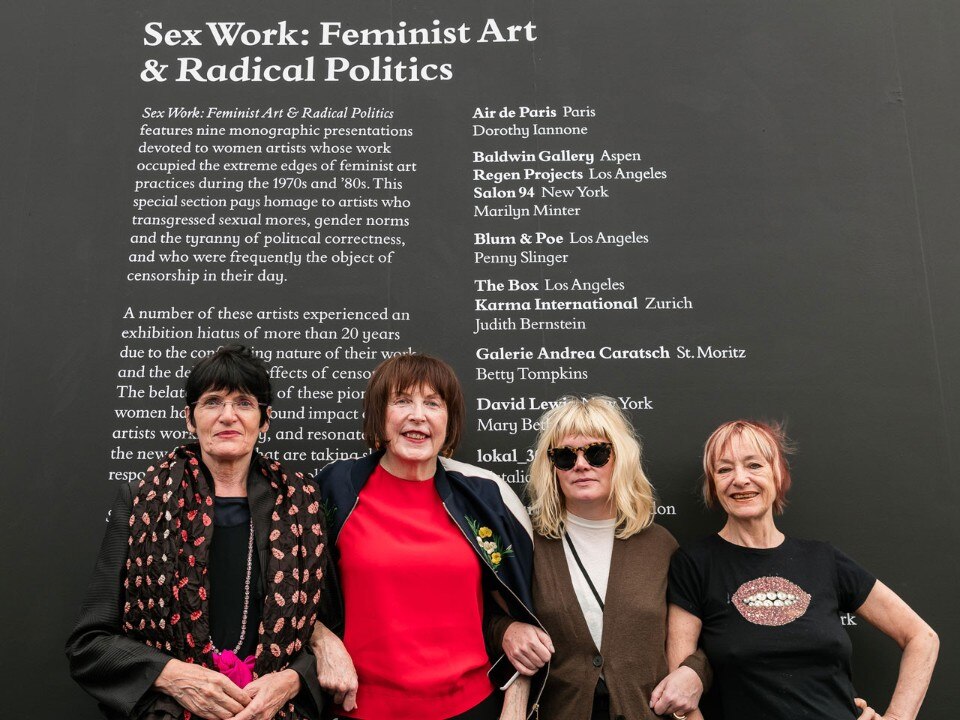

A few days later, inside the great Frieze marquee in Regent’s Park, the theme of the body resurfaces forcefully. This year there is a specific section titled “Sex Work: Feminist Art and Radical Politics” by Alison M. Gingeras. A compact cluster of galleries is showing works by Dorothy Iannone (Air de Paris), Marilyn Minter (Regen Project, Salon 94, Baldwin Gallery), Penny Slinger (Blum&Poe), Judith Bernstein (The Box, Karma International) Betty Tompkins (Andrea Caratsch), Mary Beth Edelson (David Lewis), Natalia LL (local_30), Renate Bertlmann (Richard Saltoun), and Birgit Jürgenssen (Hubert Winter). In this section, the female body clashes with stereotypes of heterosexist society. The artists named are true pioneers of feminism. Their work triggers a dense aesthetic and theoretical debate around the figure of woman. In the “Sex Work” section we find some items on the market for the first time, not having initially been designed for sale. The echoes of the feminist revolution of the seventies are now entering fully into the art system and fair circuit, prompting an inner questioning of relations between the politics of the body and its commodification.

The body, as a medium for protest and the language of struggle, also appears in SPIT! (short for Sodomites, Perverts, Inverts Together!) by Carlos Motta, John Arthur Peetz and Carlos Maria Romero. Into the marquee, the artists bring the voice of a revolution that draws on the past, but looks to the future. By compiling a reader of queer manifestos and drafting five new ones, SPIT! declares war on those who feel different while affirming their non-assimilation to the mass. In the space-square between the restaurant and the VIP Lounge, a wooden chair helps them express the power of speech. From this improvised podium, a group of performers active on London’s queer scene shout words and mime the gestures of the manifesto, contrasting themselves mentally and physically with the sounds and garments of the viewers.

The debate about the body continues in works by many artists in other sections of the fair. For instance, the artist Lili Reynaud-Dewar (Emanuel Layr) prints some statements on fabric titling them with the roles of various participants in the system (curator, museum staff, activist artist...). In the Small Tragic Opera of Things and Bodies in the Museum, the words of Reynaud-Dewar's statement are recited by a voice and worn by mannequins or exhibited as garments trapped between panes of glass.

Language and the body are also central themes in Paul Maheke's Seeking After the Fully Grown Dancer *deep within* (Sultana). The artist performs a choreographic score interleaved with the communicative and evocative presence of subtitles in the absence of sound.

Finally, Georgina Starr's Androgynous Egg takes us back inside a small theatre at the fair. This time the ephemeral architecture is pastel-coloured and strong lights illuminate a group of women wearing offbeat garments. One is present only with her head resting on a table and her voice orchestrating the others’ movements. A great piece of pink chewing gum and a stage curtain made of eggs are other properties in this new physical and visceral dimension. Far from being embodied in a specific artistic language, it seems to create a completely new one.

© all rights reserved