As technology, the diorama definitely has a high ideological content. The exhibition “Dioramas” devoted to it at the Palais de Tokyo, more panoramic than dioramic, retraces the stages in its history in meticulous detail. The introductory section beguiles visitors, immersing them in its history from the early eighteenth century down to the present. In each room the cathartic power of these beautiful vitrines, mechanisms of presentation celebrated in the Arcades Project and in the steps of the flâneur as voyeur, appear as reality heightened by the invention of effects, gadgetry and the successive contrivances of theatrical automata and marionettes. They could be scenographic or purely contemplative. It is a universe of lighting technicians, sculptors, botanists, modelers, painters, carpenters, but above all script writers. Fiction and the ability to tell stories are central to the strategy of the diorama.

However, the influence of dioramas on museum and exhibition strategies in contemporary art might have been eclipsed, if the sole idea behind the exhibition was to present dioramas as a pure critique of the idea of display. It is a pity that the final outcome of contemporary dioramas is the part presented with the weakest focus, in what is still a fine exhibition.

It certainly piles up the devices and effects of reality that, from the fetish to the image, redefine the historical result. The exhibition is splendid on the plane of research, but it lowers its sights when its ephemeral landscapes touch on the present.

Concretely, Kiefer’s diorama/big box is markedly inferior in its ability to engage the viewer. But it is perfectly natural that the romance of all his “dioramatic” painting is celebrated in the imprecision of the great Hall of Dioramas that closes the show. Duane Hanson’s hyperrealism, or the images projected from the closing scene of The Truman Show, close the interplay of successive samples. Some of these were very poorly commissioned to the point of diminishing artists thought of as having made the diorama their hallmark.

This is the case with Mark Dion, who has made an undeniable contribution to the creation of tactile archives. He is a great explorer of museum forms and the rhetoric of museum facilities. His Paris Streetscape tries hard to create a decidedly trashy image of the very idea of being on the spot, and this is precisely because the exhibition exclusively celebrates the illusionistic aspect of its theme. The whole of the first part is truly too fine to miss, comprising Neapolitan nativity scenes or the ecstasies of penitent Magdalenes, like the one by Caterina de Julianis from 1717, and examples from ethnographic museums, so great is the nostalgia for the old Musée de l’Homme. But the curatorial team is intent on tracing only a material history of the diorama. It does this through splendid examples, such as the late nineteenth-century aesthetic with the taxidermy of Rowland Ward or Carl Akeley. We enter powerfully into the discordant interplay of the antithesis between reality and fiction. Or rather the idea of forging a simulacrum of authenticity out of falsehood. Even a single fragment of Damien Hirst’s latest contrivance at Palazzo Grassi would have conveyed the idea better.

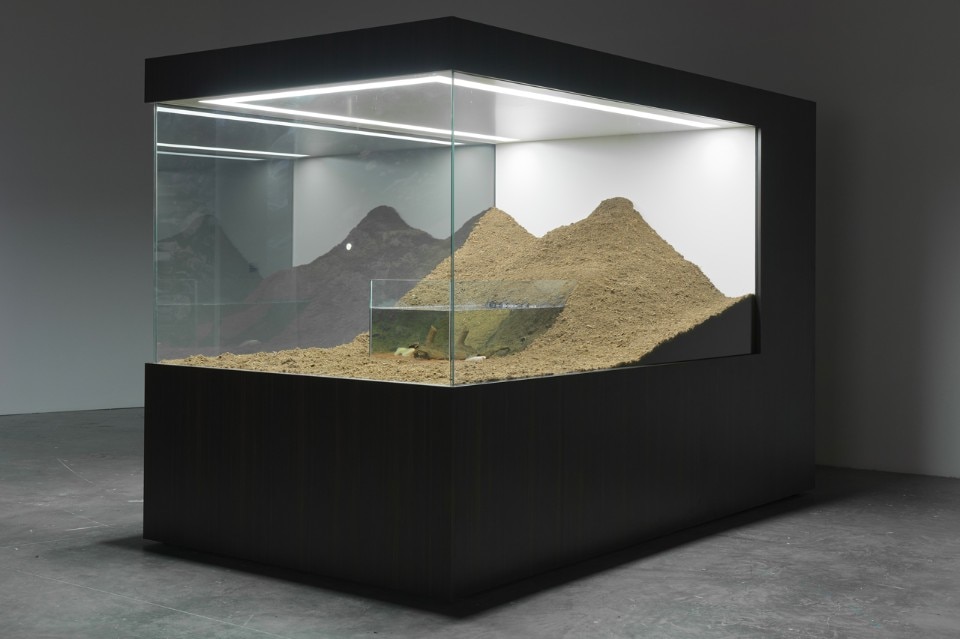

In this way the notion of the phantasmagoria described above reappears. It is the repression of the labour involved that renders intelligible the phantasmagoric content of the artistic gesture in its relation to advanced capitalism. The most concrete examples are Richard Barnes’s splendid series of photographs devoted to the maintenance of dioramas of all sizes around the world, or the elegant untitled work by Mathieu Mercier, with a pair of axolotls swimming elegantly in a minimalist aquarium. It is only at a precise moment and in the tamed public eye that the epiphany takes places.