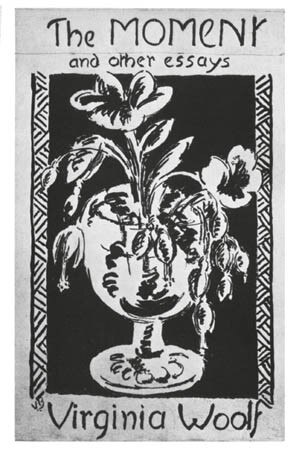

Try to picture this: Virginia Woolf is using some stitch or another to embroider or weave the back of a chair designed by Duncan Grant. Meanwhile, Duncan’s sister Vanessa Bell has been designing the cover for Virginia’s The Waves, and Percy Wyndham Lewis, between one Blast and the next, is painting a portrait of Cecil Beaton’s photograph of Edith Sitwell with her brothers. The three Sitwells get their Villa di Montegufoni in Val di Pesa frescoed by Gino Severini, and then, with much ceremony and affectation, they all rummage among leftover balls of wool for socks to send to Alec Guinness (as recalled, some years ago, by Alberto Arbasino). But what is this? A hoax, the script for a play, a petrified fable? No, it is all true.

Outlining a mixture of illustrious personalities and jesting individuals can give only the faintest idea of one of the most adventurous and daring artistic periods of a still unknown 20th century. They were decades obsessed with the New and the Modern, when London and Italy were the select crossroads of inventive new languages in all the arts. The years between the two wars witnessed, perhaps for the last time in the west, a cultural and social phenomenon of intersecting initiatives by poets and painters as well as of “divine socialites”, eccentric cosmopolitans, and artists as patrons of their own colleagues.

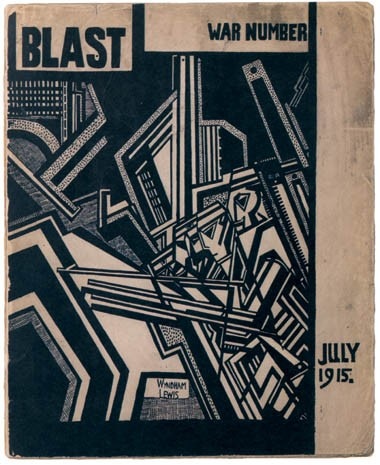

For example, the poets Ezra Pound, Hilda Doolittle and T.S. Eliot, the sculptors H. Gaudier-Brzeska and Brancusi, the writers Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence were all allied in their friendships and intentions with experimental groups in the visual arts and design. One also thinks of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo in Paris, of the three Sitwells divided between England and Tuscany, of the English Futurists in London. Journals like Blast (“a young racket”) were started and the first attempt at design (“Omega Workshops”) was made by the art critic Roger Fry and two painters, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. As well as being friends, all these people were frequently the subject of scandal and then of acute insolence and erudite disputes. A few of them were charismatic leaders with numerous supporters. But together they formed a remarkable chorus made up of scholars of rare culture, well-bred and ill-mannered ladies, languid and stubborn young men, artists gripped by paranoia and eccentrics galore. There were also imbalanced, vampire-like creatures, psychiatrically interesting cases, personalities plagued by identity crises and others afflicted by hypertrophic egos. But when we look at their works, a world of mind-bogaling breadth unfolds before us. Only a handful of intellectuals actually saw, knew and bought those works since the chroniclers of the time only reported the social and sentimental excesses of the men and women concerned.

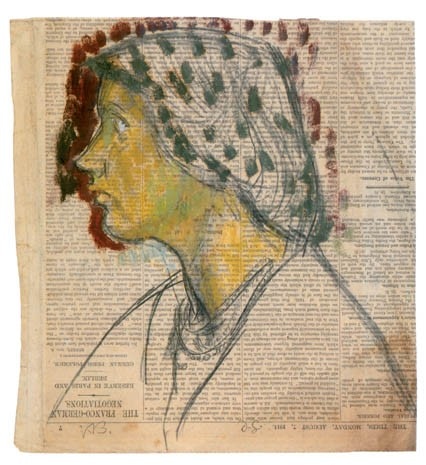

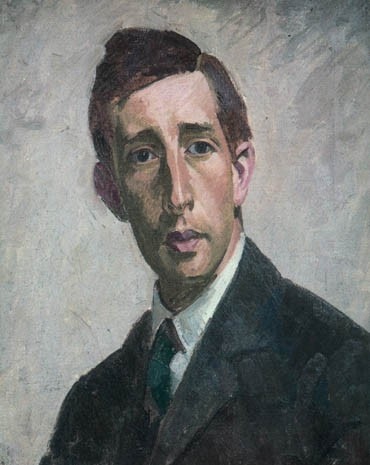

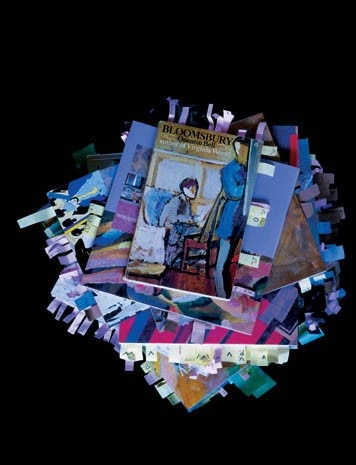

With her beloved, handsome and homosexual Duncan Grant, who was in turn infatuated with David Garnett (who was desperately fond of John Maynard Keynes), Vanessa Stephen (Bell after her marriage to the art historian Clive) made furniture, decorated fabrics, bowls and screens. But at their home in London’s Bloomsbury district (the name that came to be associated with the group) all their other friends and relatives were busy writing, typesetting, editing and painting: from her own husband Clive Bell to the economist J.M. Keynes, from Roger Fry (with whom Vanessa had concluded an earlier affair) to the historian Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard. In short, they were like a large family (but also a working group), joined by others such as D.H. Lawrence, Bertrand Russell and all the members of their variously connected circle.

The Omega Workshops were created by Fry for the production of applied arts and the products made there remained anonymous. Also part of the group was Percy Wyndham Lewis, who drafted the manifesto of “Vorticism”, published in the first issue of Blast. Lewis was also the founder of the “Rebel Art Centre”, another joint studio that rose in opposition to the Omega Workshops. Its aim was to represent the more intransigent wing of the British avant-garde since it looked upon the representatives of Fry’s group as being “too polite”. When Edith Sitwell’s brother, Osbert, at the college of the old imperial eunuchs in Beijing, was asked if there were any such institute in London, he replied: “Oh yes, it’s called Bloomsbury” (as reported by Alberto Arbasino).

Osbert, the novelist and essayist, was the brother of Sacheverell, poet and writer, and of Edith, the legendary writer and poetess, also known in the music of Stravinsky for Façade, the “divertissement in words and music” created in collaboration with the composer William Walton. Portrayed by Roger Fry and the vorticists, and photographed by Man Ray and Beaton, who in those years were taking portraits of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Edith had been introduced by the American writer to the Russian painter Pavel Tchelitchew, who was at times a practising homosexual and who became one of the most important figures in her life.

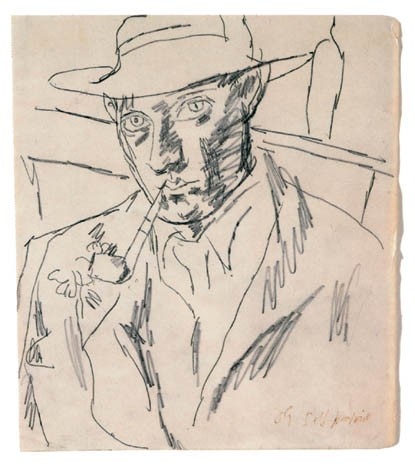

Also among the British vorticists was Dorothy Shakespear, who married Pound and designed the covers for many of his books. Ezra Weston Pound (who made his own furniture for his house in Rapallo!) made his debut thanks to the prestigious love of Hilda Doolittle, known as H.D., one of the first patients and illustrious friends of Sigmund Freud. With her, Pound founded the movement called Imagism. While he was protecting Eliot and Joyce and working on translations from Confucius, he had his portrait done by the “vort-photographer” Alvin Langdon Coburn, by Brancusi and by Gaudier-Brzeska (which incidentally made up the first exhibition held by Guido Le Noci at the Apollinaire gallery in Milan and which was photographed by Ugo Mulas).

While not all of these retraceable works and exchanges in Europe may be among the loftiest achievements of the last century, they are most certainly among its most seductive and curious. And besides, the project for an exhibition (and for a book-album-catalogue) lies not in all the results to be checked, but in their story.

For this exhibition project a series of texts were consulted, from which we have extracted the published visual papers as if they were quotations:

AA.VV., Ezra Pound e le arti. La bellezza è difficile, edited by A. Beolchi, M. Cecchetti, V. Scheiwiller, Skira editore, Milano 1997

AA.VV., Blast:Vortizismus - die erste Avantgarde in England 1914-1918, edited by Karin Orchard, Ars Nicolai, Hannover 1996

AA.VV., The Sitwells, edited by R. Gibson and H. Clerk, National Portrait Gallery Publications, London 1994

P. Ackroyd, Pound, Leonardo Editore, Milano 1990

J. Beechey, R. Morphet, R. Shone, The Art of Bloomsbury, edited by R.Shone, Tate Gallery Publishing, London 1999 Q. Bell, Bloomsbury, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1986

V. Nicholson, An Artist’s Home: Charleston, The Charleston Trust, Charleston 1999 The National Trust, Virginia Woolf and Monk’s House, London 2000