This article was originally published on Domus 1043, February 2020

The name “Lin’an” translates as “imminent safety” reflecting the story of the warring Song period (960-1279) when China was divided into two halves but peace eventually prevailed. It is a town with a rich history that has been long over shadowed by the growing influence of its major urban neighbour and provincial capital, Hangzhou. Although Lin’an has generally languished in relative obscurity, in recent years it has sought to reclaim its heritage and status. Six years ago, it commissioned Amateur Architecture Studio, founded by Wang Shu and his wife Lu Wenyu, to design a museum that would celebrate its important historical legacy and cultural traditions.

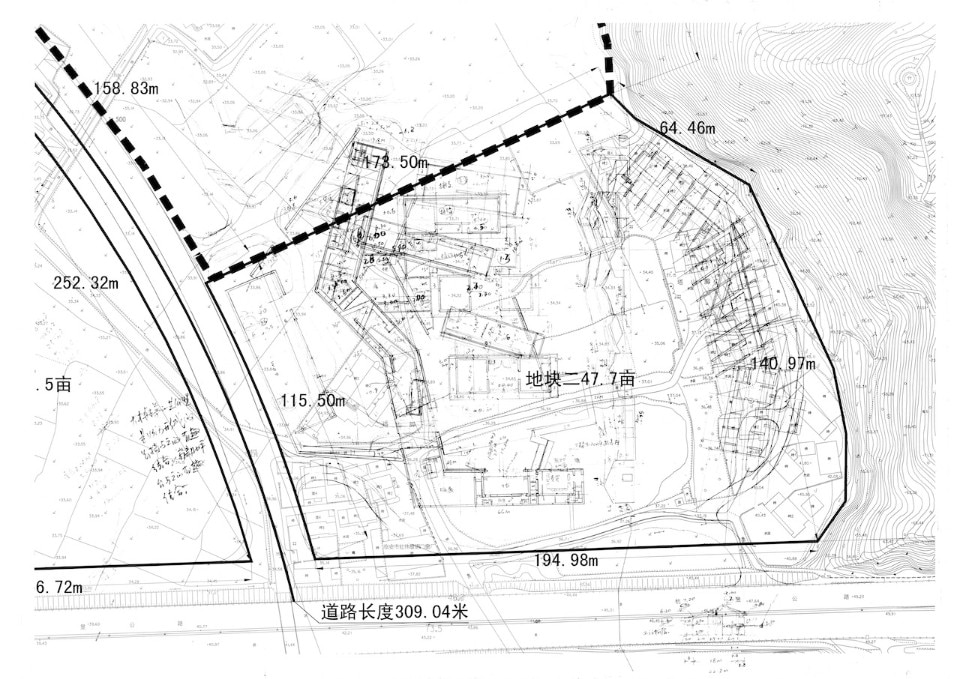

The museum is intended to be a permanent home to a collection of Qian family artefacts, derived from excavated tombs and illustrating the origins of the town. The Wuyue Cultural Park on the left bank of the Qingshan Reservoir was earmarked for development with three specific goals: to increase the profile of the town; to provide leisure and recreational facilities for locals and tourists and to provide additional opportunities for trade and commerce. Lu Wenyu explains that the site was originally a village. “We have managed to preserve a large area of farmland in the design, not only as a landscape but as a collection of memories of the agricultural history of the village,” she says.

The brief included a series of museum spaces to exhibit the rare collections of ancient ceramics, kilns and national treasures. In addition, there are cafeterias and public spaces as well as commercial spaces. The main museum is located on the southern edge of the site, fragmented into a series of linked buildings, the taller building to the north is a wing that contains car parking. Above ground this massive structure functions as a showroom for local craftspeople, like the local bloodstone engravers (a semi-precious, crystalline quartz regarded as one of the best materials for engraving seals).

Amateur Architecture Studio has played with multi-layered courtyards before. The practice’s earlier work – most notably its Ningbo History Museum (2003-2008) and the Xiangshan Campus in China’s Academy of Art (2004-2007) – were feted by Lord Palumbo at Wang Shu’s Pritzker Prize-winning ceremony in 2012 as “bargains between monumentality and intimacy; between past and future; between painterly and tectonic; between public and private space”. Indeed, Wang consistently confronts contradictions and uses the memory of the site as a symbolic driver for contemporary meaning in his built form.

Since he burst onto the world stage, a considerable amount of competition has emerged from a new generation of Chinese architects, but his authority continues partly because of his international status, but also because he is a well-respected head of the Architecture department at the China’s Academy of Art.

In Lin’an the physical topography has played a more significant part in the overall concept than in many of the Amateur Architecture Studio’s previous concepts. Here, the buildings meander up the site, following the contours. Surrounded by lush vegetation, forests, dramatic mountain ranges and a vast reservoir linked to the network of waterways that criss-cross the Yangtze river basin, Lin’an is one of the most successful forestry districts in China with a long-established ecotourism industry. While materials, workmanship and storytelling still remain a central feature of the Amateur Architecture Studio’s narrative, the historical and ecological context of this site is written large in the Lin’an museum’s overall programme: an opportunity for the architects to merge their architecture into the landscape.

As a self-professed member of the literati, Wang Shu allies himself with the Chinese intellectuals of the Tang and Song dynasties who used painting and poetry to display their erudition and cultivated status. For him, architecture is more than the sum of its parts. It is a moral virtue. This philosophical approach, when applied to the overall site, draws on the art of Chinese landscape painting and knowingly responds to the natural, historical and cultural setting.

Specifically, here Wang has drawn on the work of Li Tang, the most famous of the classical Southern Song painters and has utilised his technique of accentuating the far and middle distance. Wang notes that “the cliffs soaring on one side recalls the northern colossal mountain style and the villages on the pond on the other recalls the sceneries of southern farmlands.”

A guiding principle for this project was to leave the existing hillside, farmland and waterways untouched. This is a figurative reminder of the efforts of King Qian to protect and preserve the region from invasion. In this way, the site was to be symbolically protected and conserved

By stepping the building up in proportion to the slope of the mountain, he creates what he calls “architecture as mountain.” In life as in art, the space between a river and a mountain “would be naturally left for farmlands and modest dwellings”, he says, and this determines the form and massing of his architectural intervention at Lin’an. A guiding principle for this project was to leave the existing hillside, farmland and waterways untouched. This is a figurative reminder of the efforts of King Qian to protect and preserve the region from invasion. In this way, the site was to be symbolically protected and conserved. To cut off the traffic noise, the buildings form a physical barrier along the eastern edge of the site, creating an oasis of calm (save for the hordes of tourists within) and an enclosed space housing the buildings and extensive landscaping.

Indeed, there seems to be a military typology employed in the design of the museum. Once admitted though the ticket hall, visitors enter an austere walkway of stone floors and heavy walls reminiscent of a fortress gatehouse before walking under a bridge and into an enclosed public courtyard. Occasionally, the accessible lower level windows have been provided with heavy concrete faux shutters, par- tially open, emphasising the sense of confinement: a curiously post-modern touch amidst the traditional fayre. Visitors are clearly being directed to the entrance and guided throughout the entire experience with warlike precision.

The rich tectonics of the buildings are only to be expected in this architect’s work; with rubble stone walling, locally sourced bamboo and rammed earth walls., but there are compromises too and rammed earth has been replaced in certain locations with rendered concrete for structural and cost reasons. Similarly, the timber roof structure with dramatic interlocking dougong details at the eaves is supplemented with steel beams, concrete portal frames and steel ties. Lu Wenyu again: “The construction company had never used many of our construction methods before. So, every one was an experiment.”

Amateur Architecture Studio’s projects always tend to stand or fall by the attention to detail by local craftsmen and this project demonstrates that they are getting better at explaining and supervising the work, improvements that have come from experience, as well as a more knowledgeable workforce. Although this generally pays off, the use of wicker shuttering has produced an imprint in the concrete surface reminiscent of asbestos panelling.

However, overall, the workmanship is of a particularly high standard, testament to the dedicated control of the construction process by the architects. Although the public square is inexplicably cut off from the water and rolling landscape beyond by a locked glazed screen, it does provide much-needed shade, seating and refreshments. From here, entry into the museum is up a short, ceremonial staircase, across an open cloister (demarcated by some finely detailed steel rods and ties) and into the first hall.

Each of the following museum spaces, entered in turn in a linear progression through the building, are of a quintessentially Chinese village-hall design, an open-plan space with a duo-pitch curved roof expressed internally to mirror the external form. Some of these display spaces are interlocked, others are connected by rather incongruous enclosed ramps. Altogether, the buildings step up the slope in a strict hierarchy of rooms, which also reflects the structure of a traditional village. The sense of adventure is maintained with dark corridors, hidden dog-leg ramps and cramped enclosures unexpectedly opening up into the next exhibition space.

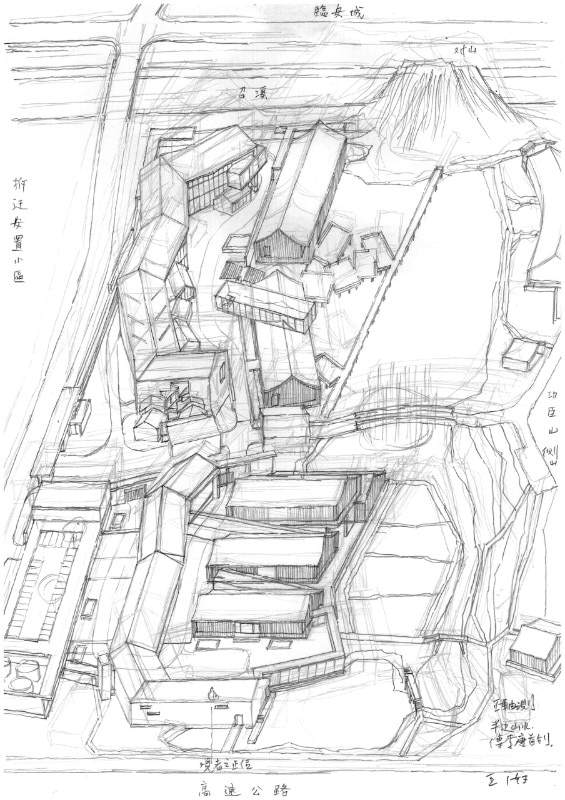

Wang Shu’s early sketches for the project may look uncomfortable or naive to Western eyes but represent a classical Chinese sense of perspective. A sketch can observe a view directly across, up and down in the same drawing at the same time. The external expression of these interconnected volumes is described as “melting away like those in the level distance in landscape paintings.” Indeed, viewed from across the pond, in the middle distance the buildings are ever present but seem to be part of the landscape rather than interventions on it. It is a creditable attempt to blend a modern museum into the natural landscape and to secrete a rural typology into a bustling urban centre.

As architectural forms, these buildings are commanding but they often represent an anti-modern critique that derives from Wang’s perception that China is rushing headlong into urbanisation and riding roughshod over its cultural heritage. Whether he could be described as a traditionalist, a radical or a one-trick pony is a moot point. The practice continues to explore the notion of cultural renewal beyond architecture very deftly.

As with the architect’s earlier, much-feted Ningbo Museum, this museum in Lin’an relies on local recycled materials – bricks, tiles, stones, gravel and mud – to mourn the loss of collective memory as the traditional fabric of Chinese towns continues to be demolished... sometimes to make way for Wang Shu’s architectural comment on that loss. In this instance, the museum reflects on the loss of the local community; the very community that was relocated a mere five years earlier to make way for the building. That said, Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu have clearly provided a fascinating architectural resolution to the challenging philosophical dilemmas of modern China.

Austin Williams is a senior lecturer in Architecture and Professional Practice at Kingston School of Art in London and an Honorary Research Fellow at XJTLU University, Suzhou, China.