This article was originally published on Domus 1086, January 2024.

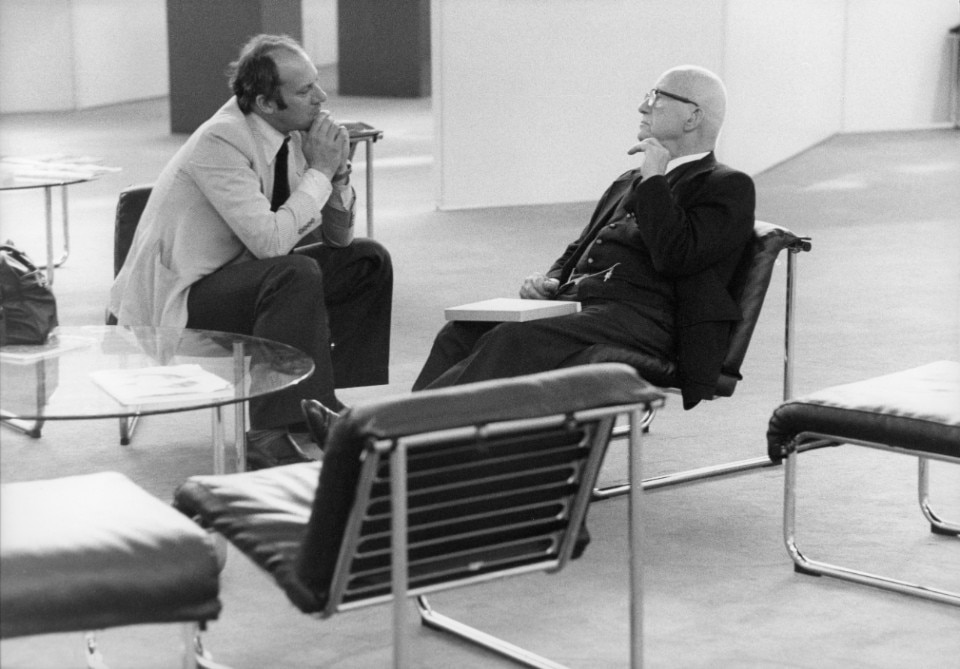

What follows is an edited transcript of a previously unpublished conversation between Norman Foster and American inventor and visionary Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). This meeting took place soon after Bucky gave an address at Foster’s RIBA Royal Gold Medal award ceremony in London in 1983. Fuller – known to most as Bucky – would pass away in Los Angeles, at the age of 87, just ten days after the event. Foster and Bucky collaborated on a series of projects following their first meeting in 1971. The pair shared a mindset that Foster describes as “an impatience and an irritation with the ordinary way of doing things”.

Their first collaboration was for an auditorium beneath the quadrangle of St Peter’s College, Oxford, UK. Although it did not proceed, it marked the beginning of a friendship and a shared approach to environmental issues, which is still very much alive today. As the architecture critic Martin Pawley observed, “Fuller understood the importance of what he called ‘design science’. He saw that the needs of the world’s burgeoning population could only be satisfied by the progressive ephemeralisation of goods and services so that higher standards of life support could be attained at a lower cost in terms of energy and resources; in other words: ‘doing the most with the least’. It was an approach that Foster quickly identified with, for he could see history bearing it out.”1

The time is coming, if we don’t blow ourselves up.

Richard Buckminster Fuller

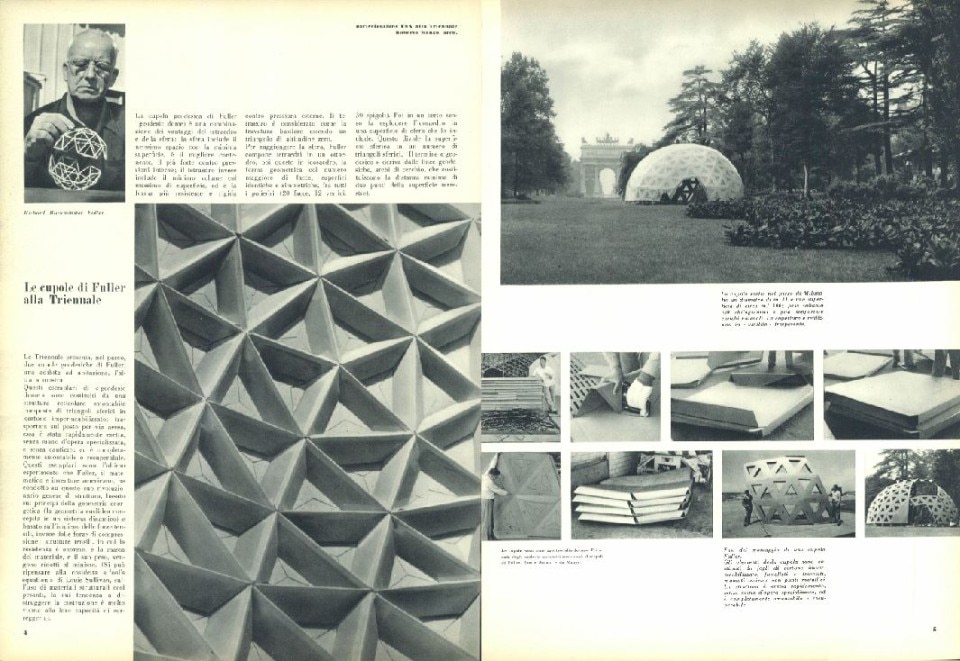

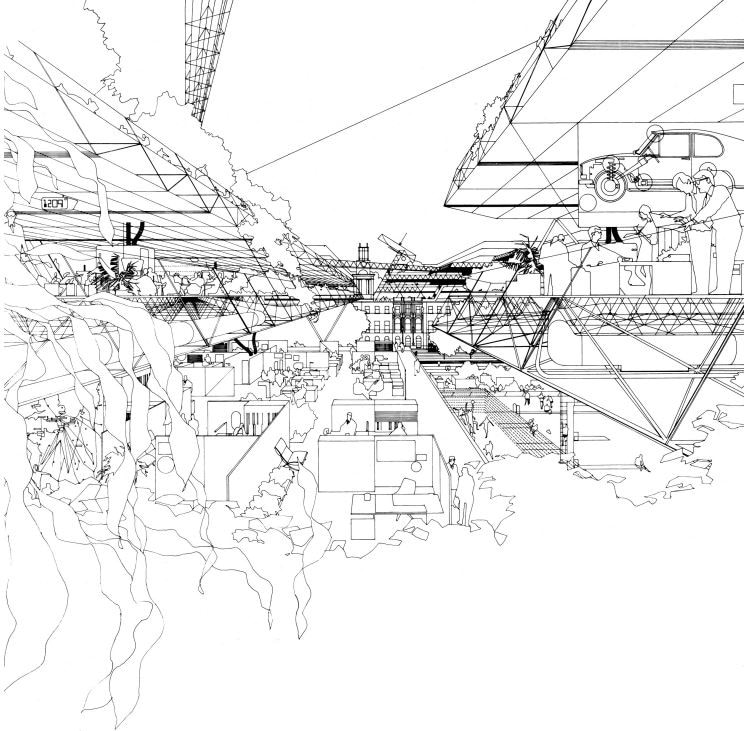

Their last venture together – about which much of their animated discussion here is focussed – was an energy self-sufficient “autonomous” dwelling based on a five-eighths sphere, double-skin dome generated by a new structural geometry that Bucky had recently developed. The external skin was to be a “fly’s-eye” dome capable of rotating independently around a similar inner dome that would support space-deck living floors. Each dome was to be half glazed and half solid – clad in polished aluminium panels – and capable of rotating with respect to the other, so that the house could be closed up at night and track the sun during the day.

The Autonomous House project represents the culmination of the two men’s exploration into the practical applications of an environmental envelope structure, which included the Climatroffice project (1971) and the International Energy pavilion for the Knoxville Expo in Tennessee, USA (1978). Two decades earlier, Fuller and Japanese architect Shoji Sadao (1927-2019) had proposed to encase Midtown Manhattan under a 3.2-kilometre-wide glass hemisphere. Writing about this Manhattan project in his 1969 book Utopia and Oblivion, Bucky explained: “Domedover cities have extraordinary economic advantage.

A two-mile-diameter dome… calculated to cover MidManhattan Island… has a surface area which is only 1/85 the total area of the buildings which it would cover. It would reduce the energy losses either in winter heating or summer cooling to 1/85 the present energy cost obviating snow removals. The cost saving in ten years would pay for the dome.”

Today, while urban-scale dome projects – like the one Bucky and Foster discuss – have not yet come to be realised, Foster + Partners and the Norman Foster Foundation are both still engaged in proposals that have a direct lineage to these pioneering projects. The scheme for the Knoxville Energy Expo – a massive single tensegrity structure with a double skin, which would have covered an area of 6.07 hectares and risen to an internal height of 64 metres – has influenced Foster’s proposal for a temporary “pop-up” Parliament under a glass dome on London’s Horse Guards Parade. Foster and his practice also retain, in their DNA, the belief that engaging with experts and a broad range of disciplines – both in-house and external – is the best approach for achieving a truly innovative and inspiring design solution. This is a conviction that emerged from Foster’s experiences at Yale and continued with the establishment of his studios and their relationships with thinkers like Fuller.

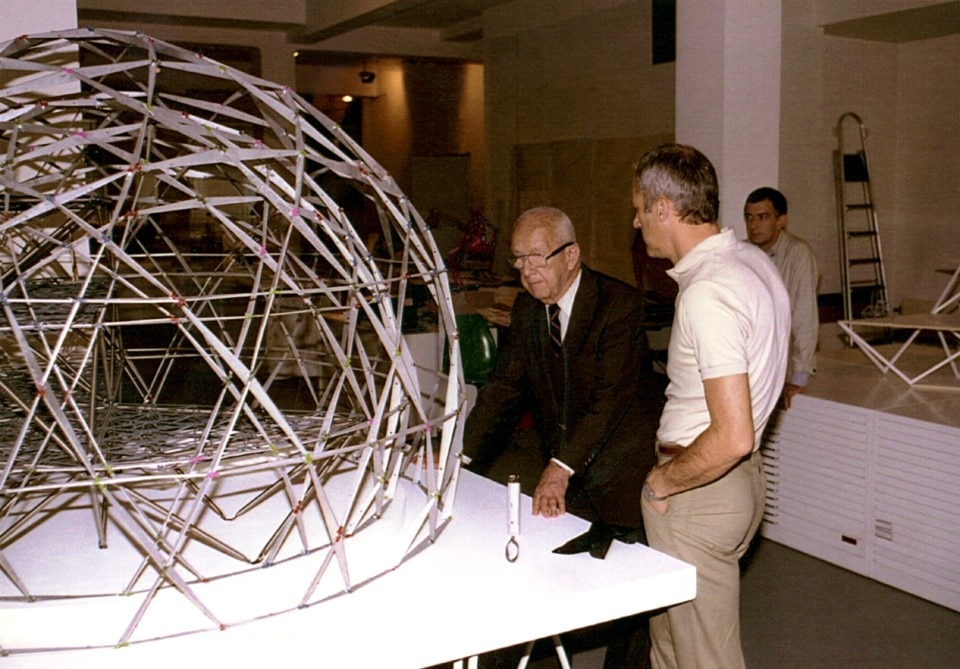

The conversation revealed here is a window onto one of the many collaborative exchanges between Fuller and the Foster Associates team. As Pawley recalls, “the [Autonomous House] design was advanced in a series of meetings with Fuller in London. A full set of design drawings was sent to Fuller’s office in California, where the final complex threedimensional geometry was calculated, and a large-scale model was made in the design studio of a US aircraft manufacturer. This was completely demountable into a kit, which Fuller brought with him to London.”2 Until recently, this model has remained the most advanced illustration of the two men’s revolutionary ideas. Now, however, Château La Coste in Provence, France, with its installations of art and architecture, has commissioned an updated version of the Autonomous House as a gallery/studio and dwelling for an artist in residence. Forty years on from their final, fervent and almost conspiratorial discussions on the project, the reality of the ground-breaking and environmentally innovative scheme may finally be becoming a reality. TW

We are going to unquestionably have whole cities under domes and have with the Autonomous House the capability of two domes – of a dome inside of a dome.

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller I thought, Norman, I had better go over with you the significance of what you have here because it is going to relate to your work. You have gotten into big things with the Hongkong Bank and gotten into big things elsewhere. But you could get into very much bigger. The time is coming, if we don’t blow ourselves up. The armaments world will begin to come into the direction of producing technology for housing. We are going to unquestionably have whole cities under domes and have [with the Autonomous House] the capability of two domes – of a dome inside of a dome. [We can] truss them together and operate them with hydraulics. Did I tell you about hydraulics? We can have circumferential tubing of carbon fibre, with very high tensile strength, and they can be squeezed into chords with a high compression strength.3 With an inner and outer dome, we can truss the two together in tension as you do an aeroplane. Once you have a compression member that is not going to yield, you can take the snow loads of a mountain!

Norman Foster Sure.

RBF So, you can truss these domes together and there will be these spaces in between the two. You could have the whole city under the dome, and you would go and live in this wall. Right?… The combination of the hydraulics, trussing and living in the shell, and in the beautiful mathematics… I think it is your world. I really woke up with the absolute necessity to say these things to you this morning. Do you get me?

NF Yes, I do. It’s a model of a larger possibility.

RBF It is incredibly strong by itself, so you can make the two domes independently. And under the dome could be an enormous growing house. You would have controlled and unlimited growth of food.

NF So, you are talking about this space, between the two domes, as a living area?

RBF Yes, this is living in here, within the wall, and this is the great community, under the domes.

NF It is a private and public relationship.

RBF I am really terribly excited for you. I think it is wonderful to keep at it and get familiar with this structure.

NF So, you are still keen to proceed on the [Autonomous House] programme? I think we should be aiming for a date next year.

RBF Yes. Lovely… It is an extraordinary structure because these are very thin members, and to have the strength that it has is incredible… and if you break thermal conductivity, you really have enormous energy conservation and that is what we are doing. That can be done in the big domes as well… I am terribly excited. Keep [the model] here; don’t let anything happen to it.

NF Absolutely. The only thing we will do is photograph it.

RBF And when you get to the point where we can truss it, then we can start to hang the stuff inside… I did a beautiful patent on the hanging bookshelves. You come in and see them hanging there and you can lean up against it and shove it; you can’t hurt it. There are three pairs crossing in tensions. It won’t move.

NF: Sounds terrific.

RBF We are going to have a demonstration of it. Thonet, one of the oldest furniture companies, is making it.

NF I’d love to see a photograph or something of it if that is possible, sometime. I’d be really interested.

RBF All the floors can hang that way, like the bookshelf…

I remember the time of this conversation very well; Shirley Sharkey was Bucky’s secretary and, in his later years, she travelled with him on his global trips. She overheard the recorded conversation and afterwards, sitting at the round table in my corner of the studio with Bucky and I, she gently corrected him about his agreeing to go ahead with the Autonomous House as a Fuller family project in parallel with the Foster version. She reminded him about his wife Anne’s dire condition in the hospital in Los Angeles where Bucky was heading after a scheduled talk at the White House following his departure from London. “You’re right, darling,” he said (which sounds overly familiar, but for Bucky it was, as in every one of his personal acts, always respectful). He then mentioned, as an aside, his own state of health and how his doctors were always surprised by his ability to treat gruelling long-haul lecturing schedules as a normal way of life, while still maintaining bundles of energy. “I always tell them,” he said, “if I want to end it then I can pull the plug anytime – it’s all in the mind.” That was the morning of 21 June 1983. Ten days later Bucky visited his wife Anne, who was in a coma and would never recover. He suffered a fatal heart attack and, 36 hours later, his wife Anne died. I remember saying at the time that Bucky decided “that it was time to pull the plug”. NF

1 Martin Pawley, Autonomous House, in Norman Foster Works 1, Prestel, 2003, p. 532

2 Ibid, pag. 547

3 “The continuous bottom tubes of the [Autonomous House’s] inner and outer domes ‘floated’ in a low-friction sealed hydraulic race which required very little fluid to support the structural load. It was a principle that Fuller had tested in the early 1970s with his ‘rowing needles’ – tubular hulled, catamaran scullers – which, as a keen oarsman, he had designed for his own use. In these, the water played the part of the hydraulic fluid. Using the same hydraulic principles for the house, it became possible to move the domes with very little effort, opening up a whole range of new possibilities.” Ibid Page 545

Opening image: Foster (left) and Buckminster Fuller visit the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia near Norwich, UK, soon after its opening in 1978. Photo © Ken Kirkwood.