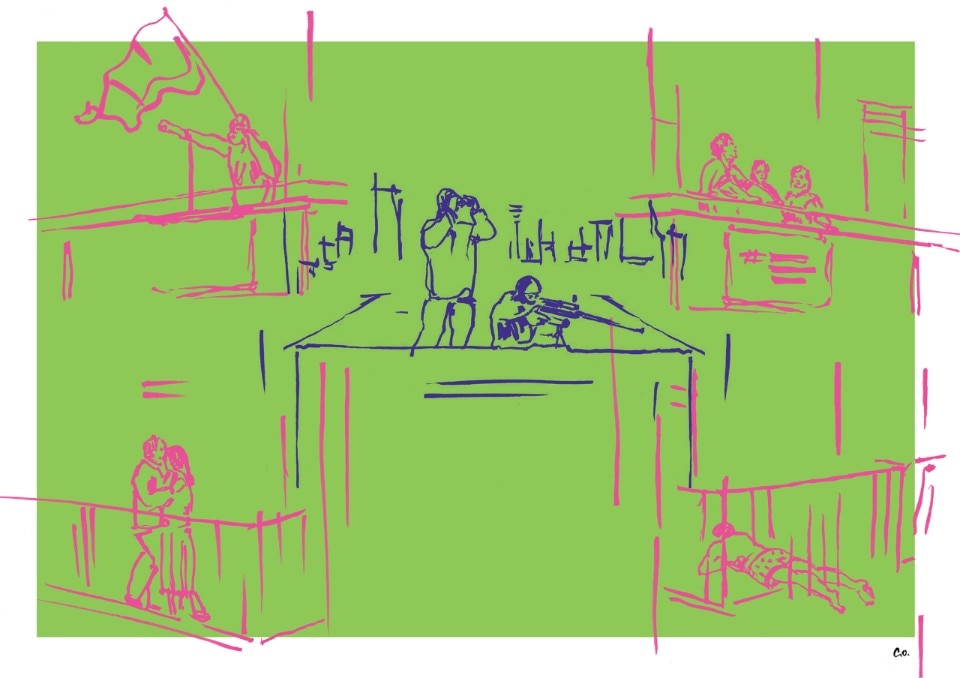

Whether it be a handcraft, a location, or a special place (as it has always represented a great place for various social interactions), the balcony is the protagonist of these sad times, of quarantine, forced confinement and disturbing hashtags. And so, when faced with the impossibility of escaping, we take refuge in that privileged space precisely because it is a liminal space, on the edge of the domestic walls, the only space that now allows us to keep in touch with the outside, with other people, even though from afar, while staying inside our own home.

And it is from here, while standing still, immobile, confined, that we participate in the “greatest challenge that Europe has faced since the Second World War.” And those who do have a balcony, they enjoy it as they probably never have before, while those who don’t have a balcony, want one more than anything.

balcony: an area with a wall or bars around it that is joined to the outside wall of a building on an upper level. (from Cambridge Dictionary)

Today, owning a balcony or a terrace, is a privilege, more than ever before. And not only because it allows us to take a breath of fresh air, to observe the city (the world!), but because “observing” has quickly become, as if by magic, a synonym for “participating”. A very limited participation, of course, but still the most active kind of participation that we are allowed today.

In a few days, the balcony has regained its most modern and democratic function: the participatory function. We once again using it as a “wireless phone”, now that, among the excesses of smart-communication, we begin to feel the need to look each other in the eyes. After all, as italian cartoonist Makkox said, “balconies were the first social media”, and the ivy and the partitions that we used to protects ourselves from the prying eyes of our neighbours, were the first “banners”.

From Persia to Sicily

Conceived in Persia and Egypt, the balcony had a specific ceremonial function, similar to that of the pulpit, and also a hierarchical one: it made the presence of someone prevail over the masses underneath the balcony. Over time, the balcony and its older sibling, the terrace, took on new functions and purposes.

Similar spaces, the loggias, had in fact become common in Greece and Ancient Rome (they were called maenianum), with mainly recreational purposes: the citizens who attended public performances, for example near the Forum, had better view of what was happening. From the Middle Ages on, however, due to the lack of sewage systems, the balcony had also taken on another essential function - that of the toilet, as Benigni and Troisi also remind us in their masterpiece movie “Nothing left to do but cry”.

During the Renaissance, the balconies became real works of art to be displayed with pride. Balconies were “status symbols" whose main purpose was aesthetic, rather than functional.

Just think of the many Renaissance palaces, the works of Vasari and Raffaello, and Florence’s upside-down balcony, whose tall corbels, small columns of the balustrade and all the decorations are built upside down, with the sole purpose of mocking the order with which, in 1530, Alessandro de’ Medici tried to make the narrow streets of Florence more harmonious and functional.

Or, later, the Venetian architecture of the 1500s, Palladio, Scamozzi...

In the Baroque period, the balcony finally took on a central role in defining the composition of the noble facades: the use of particularly complex and decorated iron balustrades became increasingly widespread (for example, Sicilian balconies are a feast for the eyes!)

To show and to confine

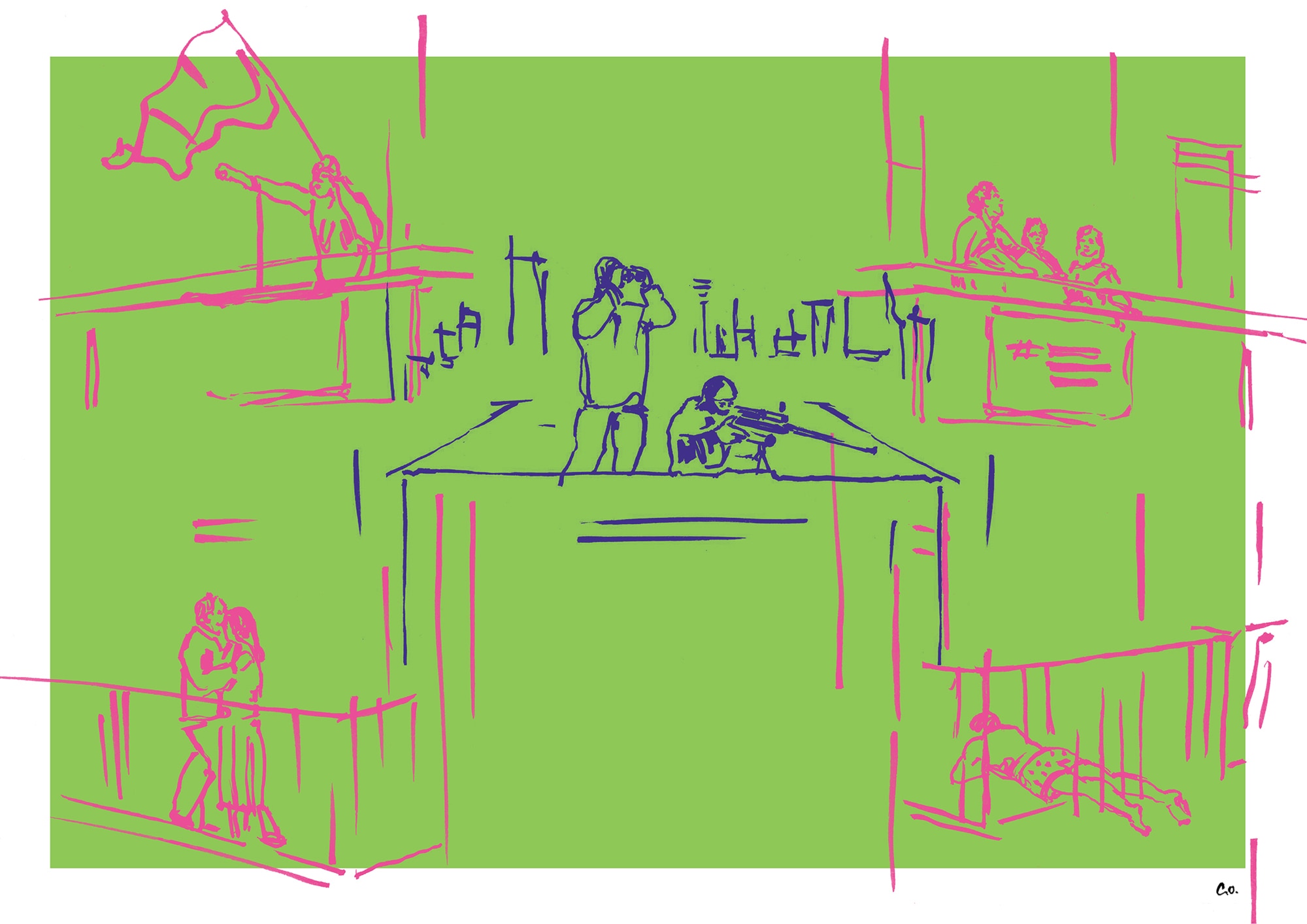

Showing yourself, always from a privileged position, has always been a common practice and, alas, during the darkest periods of modern and contemporary times, has easily degenerated: how many dictators and men of power have exploited elevated surfaces in order to always be looked up to?

And us losers, underneath, looking up: take a look, admire, and don’t touch.

This is a feeling similar to the one we experience when looking at the Majas on a balcony, Goya’s famous paintings from the early 1800s. Standing on the balcony was a typical activity for the prostitutes: the “majas” are in fact probably “put on display” on the balcony by the shady individuals looming like indefinite shadows behind them, or by the disturbing and smug “Celestina", the pimp.

Another example of a woman on the balcony, well imprinted in our collective memory, is that of the famous Shakespearean story. Interpreted as the very symbol of romantic love, unstoppable and proud, ready to fight against everything and everyone, the story of Juliet actually shows another function of the balcony.

Here, Juliet does not show herself: forced to stay inside her home by her parents and nanny, in order to meet her Romeo she is forced to hide, to disobey, to find a shelter on the balcony, the only possible space of participation and dissent for her – like us, she is locked inside her house against her will.

Being confined at home, on the other hand, has been for centuries the typical condition for women, who not by chance appear on the balconies of many stories. So much so that the writer Christine de Pizan, an ante-litteram feminist, in her Livre de la Cité des Dames (1405), imagines a place where women can be free and “far from men’s reach and sight” and where houses – strictly without kitchens – are connected to each other through a series of “galleries”, very similar to our modern balconies.

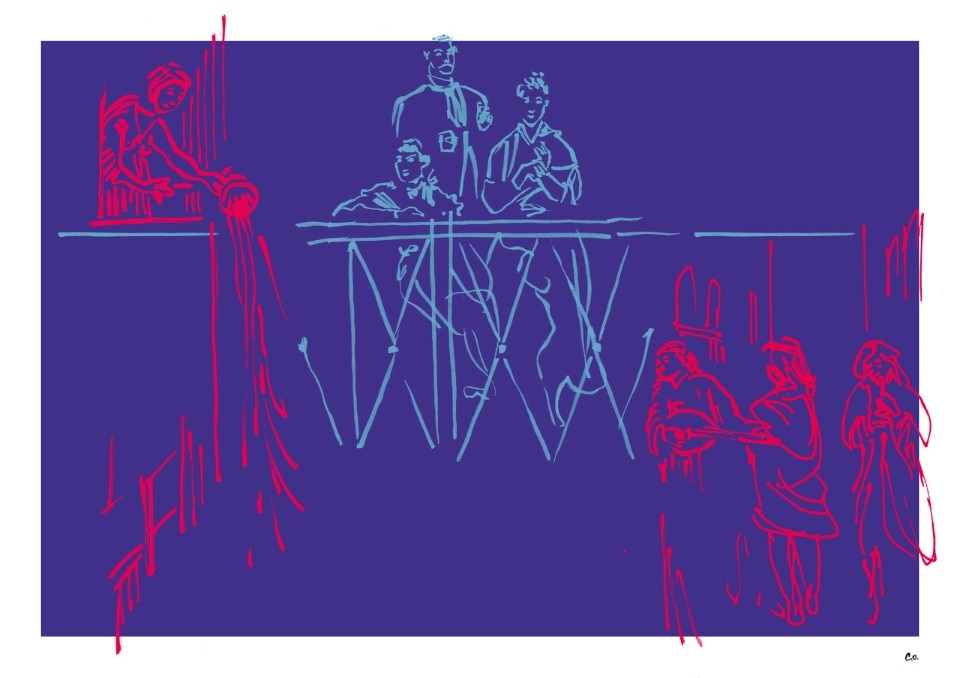

The aristocratic Parisian characters portrayed behind the green balcony rails by Manet in his famous The Balcony of 1869 enjoy being looked at, even though at the same time they observe from above what is happening in the streets. And these balcony rails provide us with the indispensable information on the social status of the four characters. Balconies had spread like wildfire following Haussmann’s audacious renovation of Paris. In the name of better hygienic norms, Haussmann, who had served as prefect of Seine from 1853 up until 1870, demolished the ancient, winding streets of the city and created broad straight boulevards, with sumptuous buildings with monumental facades and balconies, so as to make Paris look like the elegant living room of the 19th century bourgeois city.

As if from the balcony of a theatre, the four figures, all facing in different directions, lost in their thoughts and apparently detached from what is happening around them, not only watch the show, but shamelessly flaunt themselves.

The balcony of the twentieth century

There is a Spanish verb, “balconear”, which means to watch closely from a balcony, without taking part in what is happening. A meaning that makes evident what has long been the main function of the balcony.

This attitude was also recently criticized by Pope Francis, an unexpected revolutionary of the times, when he invited the younger generations “not to balconear”, but to “dive into life like Jesus did”.

And it is no coincidence that in the revolutionary era, in 1911, Boccioni made a painting with the emblematic title: The street enters the window. The painting shows the back of a woman who’s leaning against the rails of a balcony; but in the representation, interior and exterior merge into a single entity in which colours and geometries release an enormous emotional charge, a force capable of bending buildings, of breaking the gap between observed and lived life. An explicit invitation to a participation that, given the new historical social context resulting from the industrial revolution, can no longer be avoided.

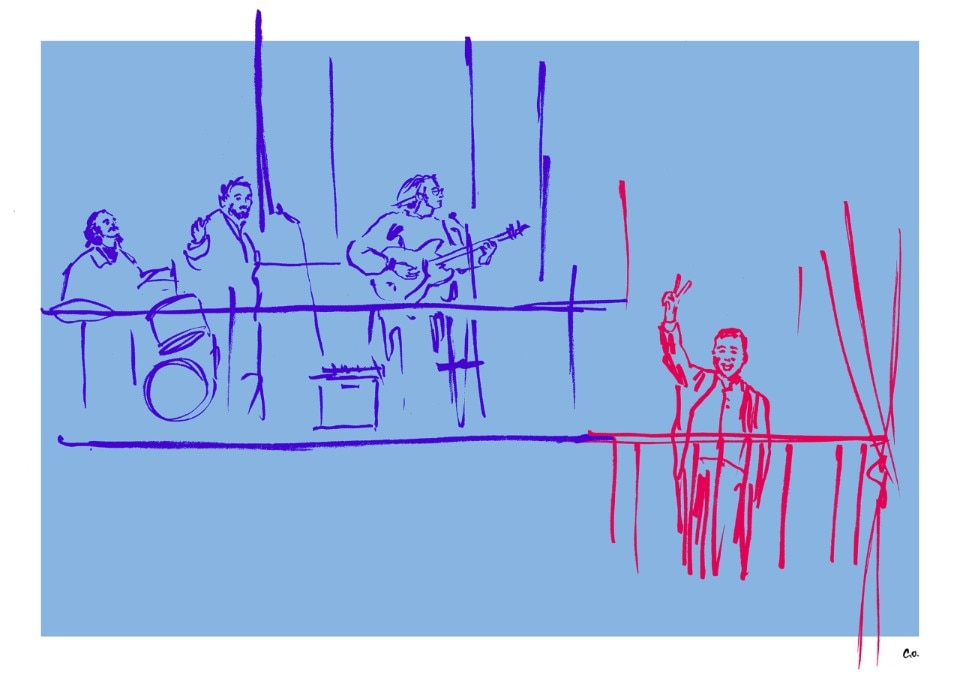

A few years later, in 1924, Moholy-Nagy suggested to some of his fellow professors (Kandinsky, Klee, Schlemmer, Muche and Feininger) to revise, on the occasion of the birthday of the Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, a photograph published in a German newspaper.

Beyond the plastic and compositional aspects, the image depicted a radio receiver with a megaphone placed on a balcony sill, broadcasting the results of the election to an attentive and worried crowd gathered in the square.

There was something disturbing about the photograph: on the one hand, the political, economic and social situation in Germany did not bode well; on the other, the crowd, gathered together waiting to hear a machine speak, foreshadowed an alienating and dehumanizing future in which machines would control humanity from above. When you think about it today, when newspapers all over the world are discussing a possible control of Society through mobile phones and satellites to stop the epidemic, it gives you the shivers.

In any case, it was precisely this period, thanks to the diffusion of reinforced concrete, that brought the balcony, after a period of further magnificence evidently recognizable in the Art Nouveau floral evolutions of the beginning of the century, to less lavish, more composed and rigorous forms, and to its even wider diffusion. And it is precisely the famous photos of professors and students on the balconies of the new Bauhaus headquarters in Dessau that demonstrate this.

A diffusion that, we must admit, was not always legal: how many unauthorized balconies were built in Italy during the 20th century?

The shared balcony, a new kind of sociality

And it was precisely during the 20th century that the “half-brother” of the balcony – the shared balcony – became widespread in the domestic sphere. Bornin the 20th century as a functional connecting element, a passageway next to a wall of a building, usually on the external side, it defined a new type of social housing, the italian “case di ringhiera”, literally “guard rail houses”, in which the balcony was used as a common space to access individual housing units, and has become the ultimate place for inter-communal social relations. Used to hang out clothes, go out for a smoke, ask for information and gossip, and organize collective events in the courtyard, it has defined more than an architectural typology, it has defined a social model of community life: the shared balcony life, in fact.

This model was revisited and revolutionized in the crazy ’60s, when Team X, the first movement to break with the functionalist model of the modern movement, was born. Among the founders of this movement, there also was our Giancarlo De Carlo who, among other extraordinary things, was the author of Urbino University Colleges: an ode to the balcony, and to the shared balcony, which is a “social engine”.

The balcony of the new millennium

However, with the beginning of the 21th century, the balcony (and with it, the terrace) became a mirror of the changing society, impudently capitalist and increasingly individualist. The balcony was no longer seen as the place where to meet other residents, but as something private, inside your home but at the same time facing the street, where you can protect yourself from prying eyes and nasty noises: it became a synonym for privilege and splendor. In the global era, the balcony, often disguised as a bio-climatic space, is the protagonist of the advertising campaigns of the many real estate promotions that have invaded the cities all over the world, including Milan.

And now that we find ourselves in this sad condition, locked inside our homes, we finally realize it, because we feel and need those social relationships.

So, we are once again looking out, we’re looking at our deserted cities from above, in a desperate attempt to have human contact, to participate, we do not want to “balconear” anymore.

In order to imagine a future in which we do not want to jump off the balcony to escape from our home, and in which situations like this, or worse, do not happen again, we really need to hear some good ideas that will help us build the life after Coronavirus.

So, to quote a hashtag created by the Napoli-based video-maker group, The Jackal: #restiamoaibalconi - #stayonthebalcony

Carlotta Origoni, graphic designer, deals mainly with visual communication, publishing and printing techniques.

Matteo Origoni, architect, is professor of museography at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and focuses on exhibit design, interior and product design.

They work, together with Franco Origoni and Anna Steiner, in the family studio: Origoni Steiner architetti associati.