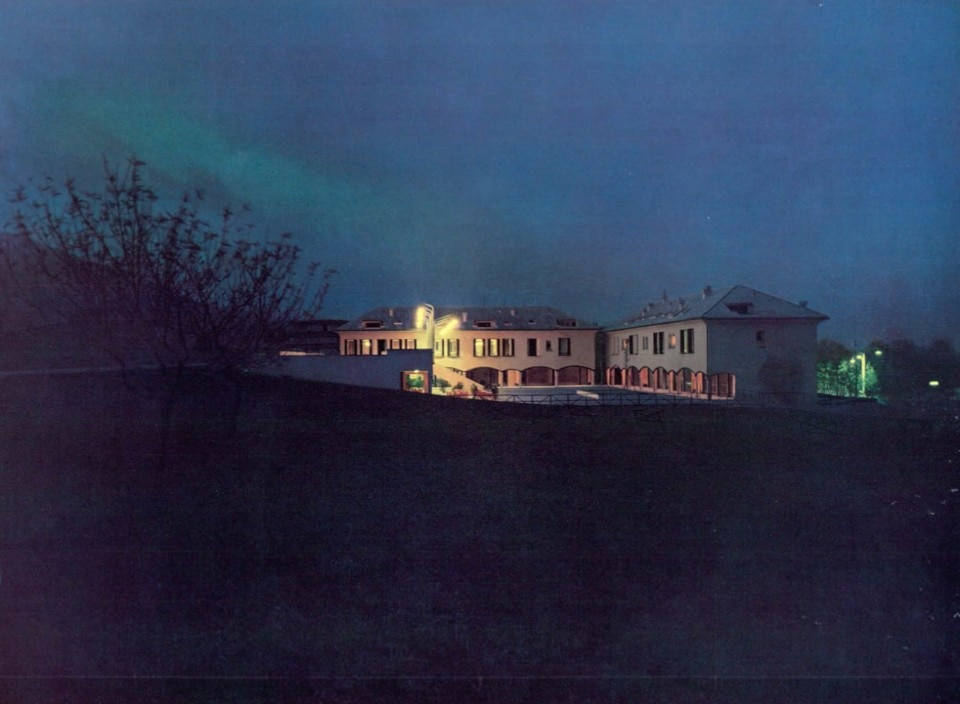

Domus first wrote about the big pine forest southwest of Arenzano, on the western coast of Liguria, in 1958, only two years after the approval of the touristic development plan proposed by Ignazio Gardella and Marco Zanuso. Over the following five years, the magazine published six essays on this innovative gated community (the first in Italy, according to Stefano Guidarini), a holiday acropolis suspended 70 meters above sea level, built for the rich Milanese bourgeoisie by the best architects of the city (among them we find Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, Vico Magistretti, Roberto Menghi and Gio Ponti).

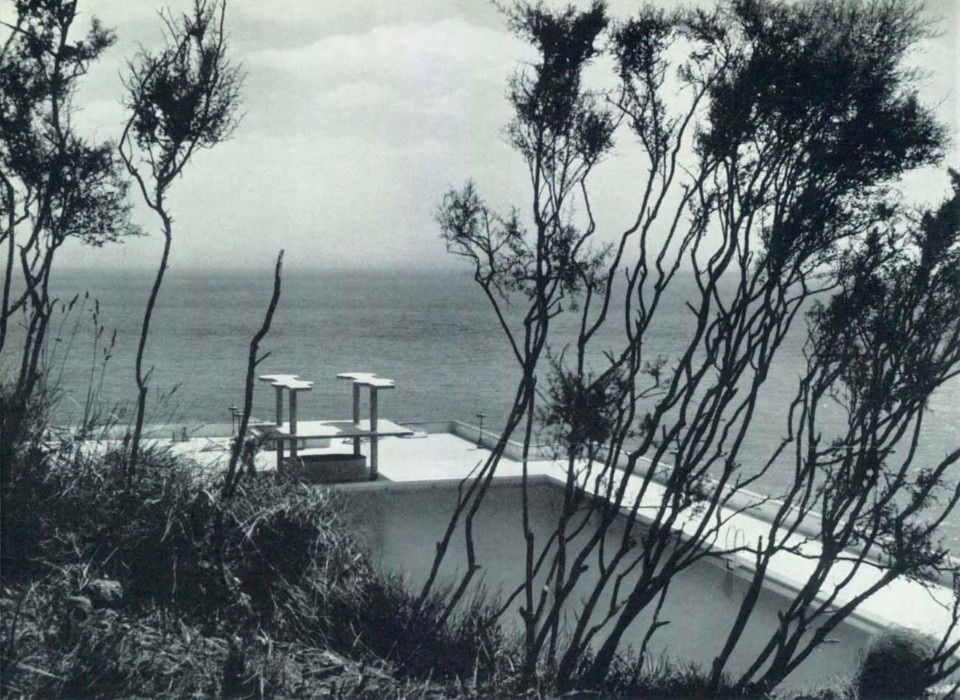

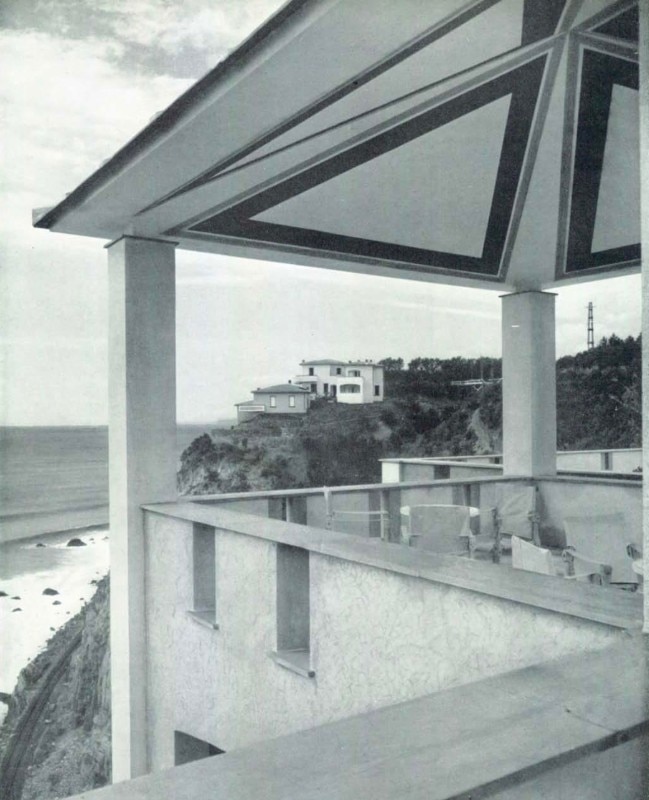

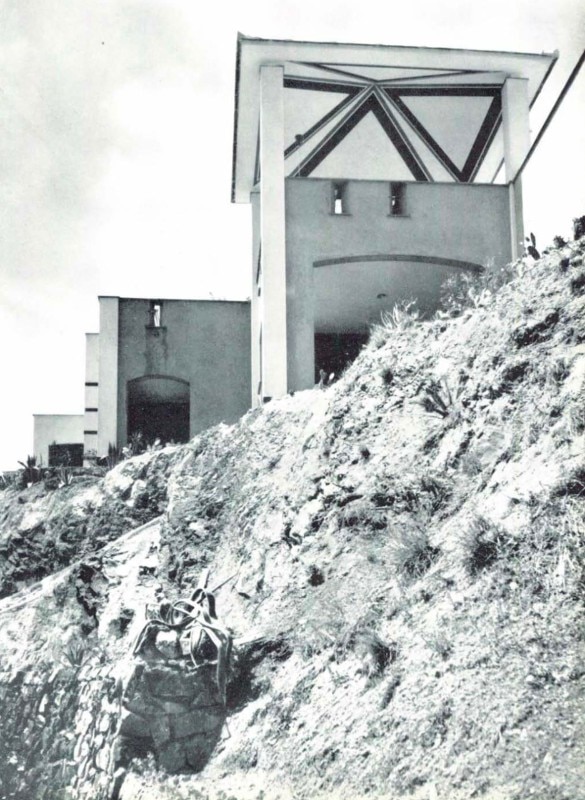

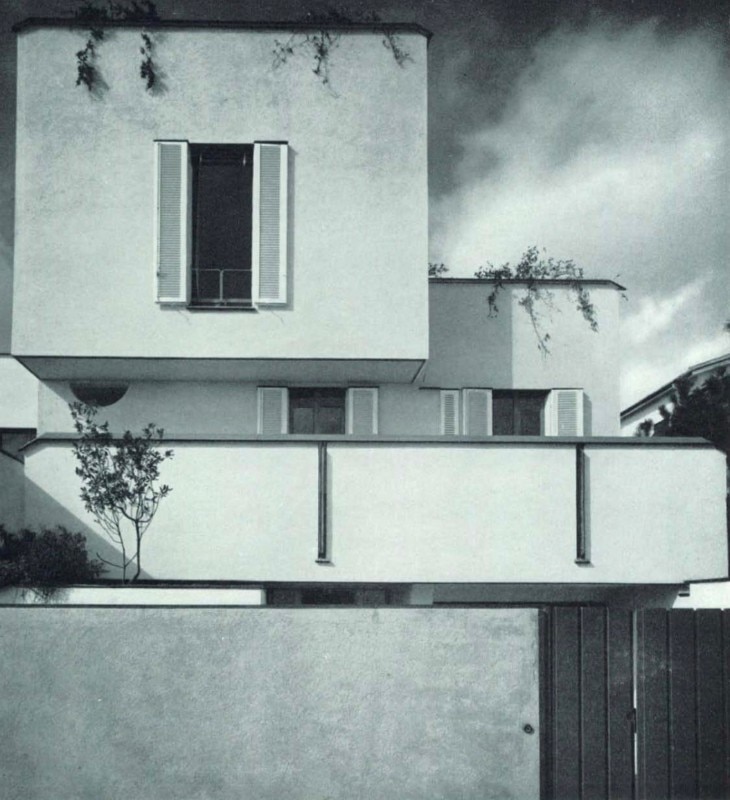

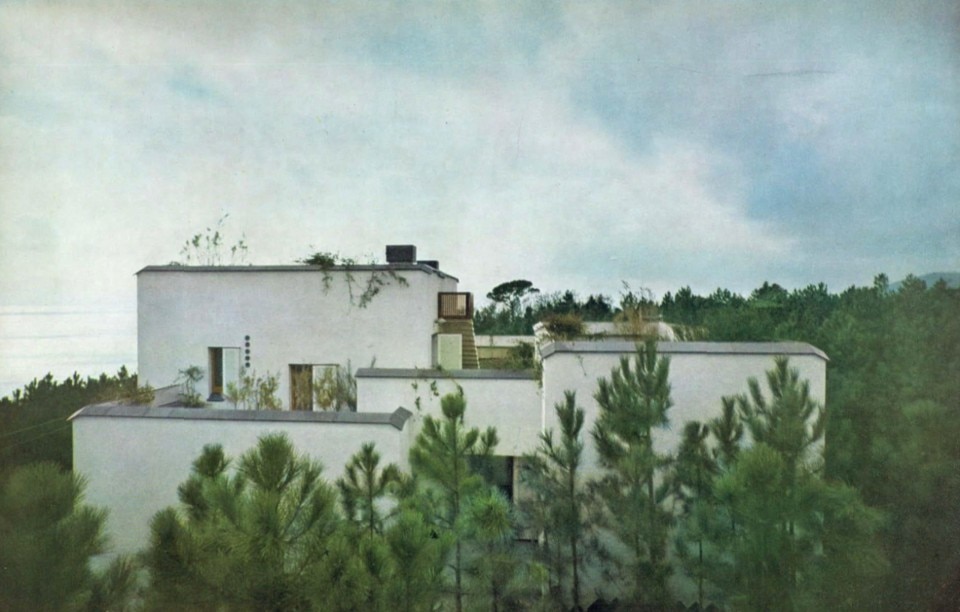

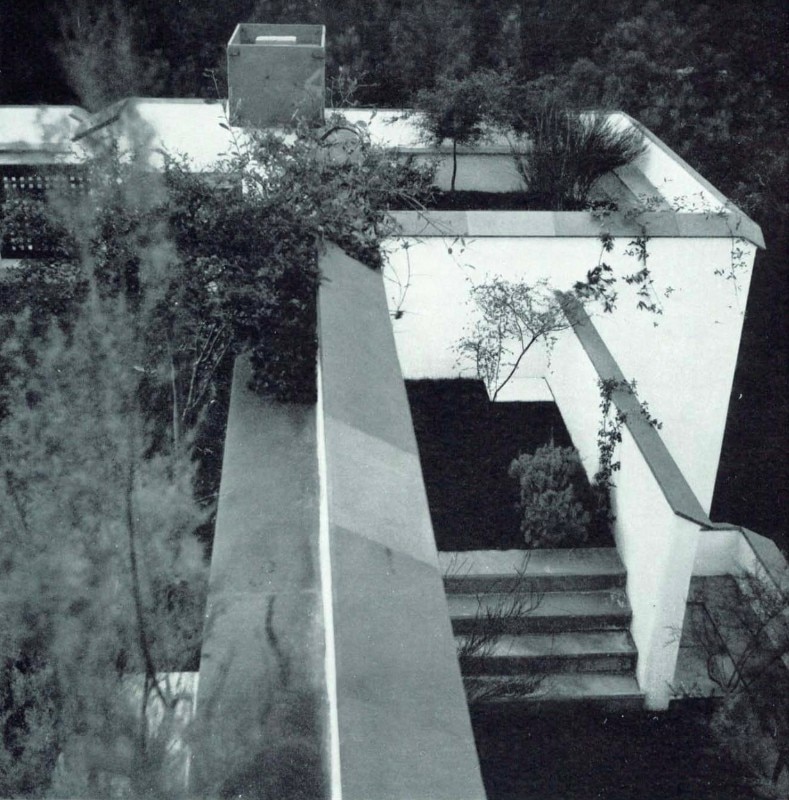

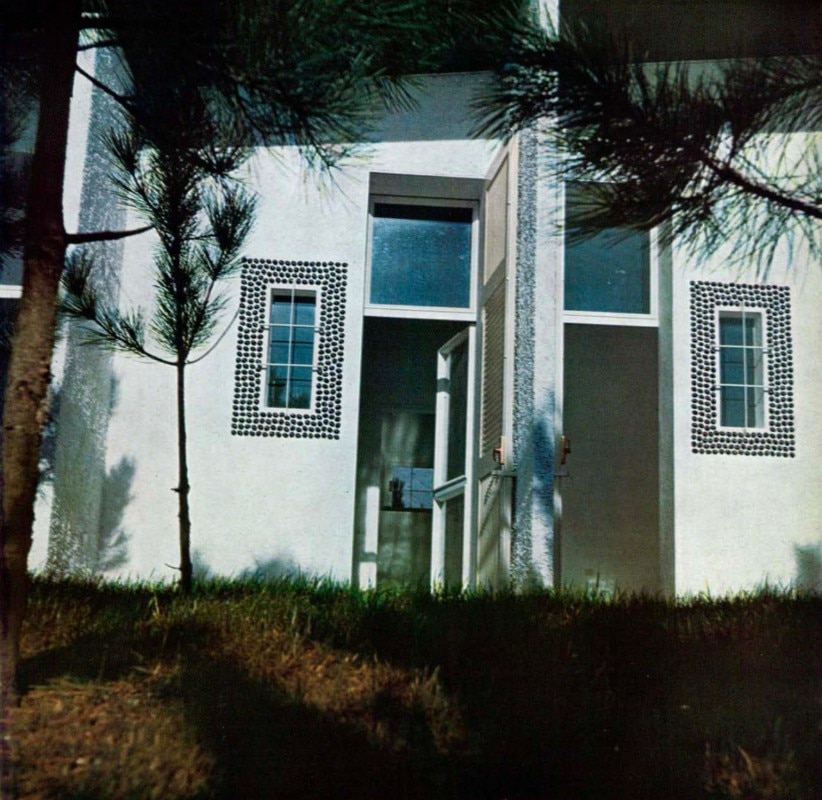

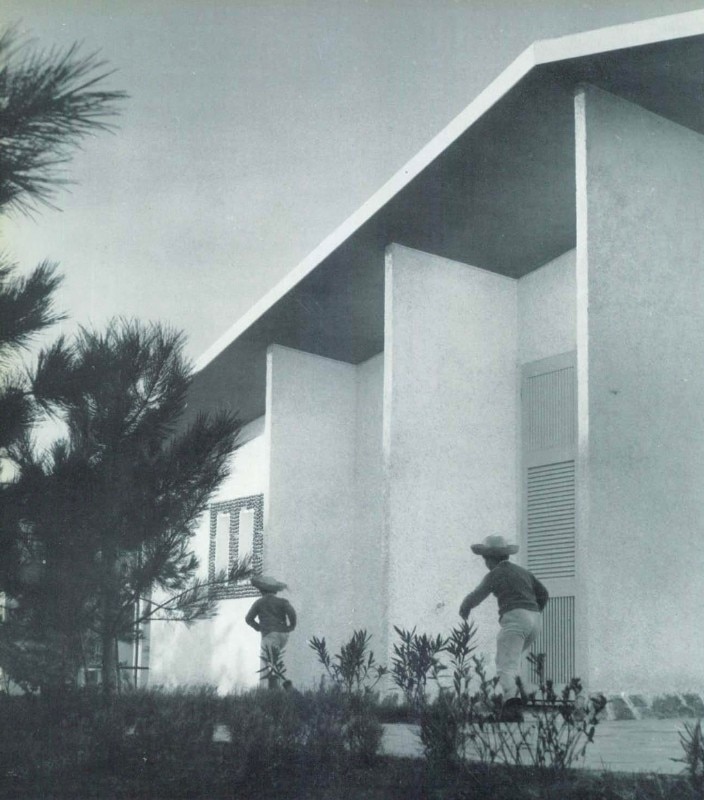

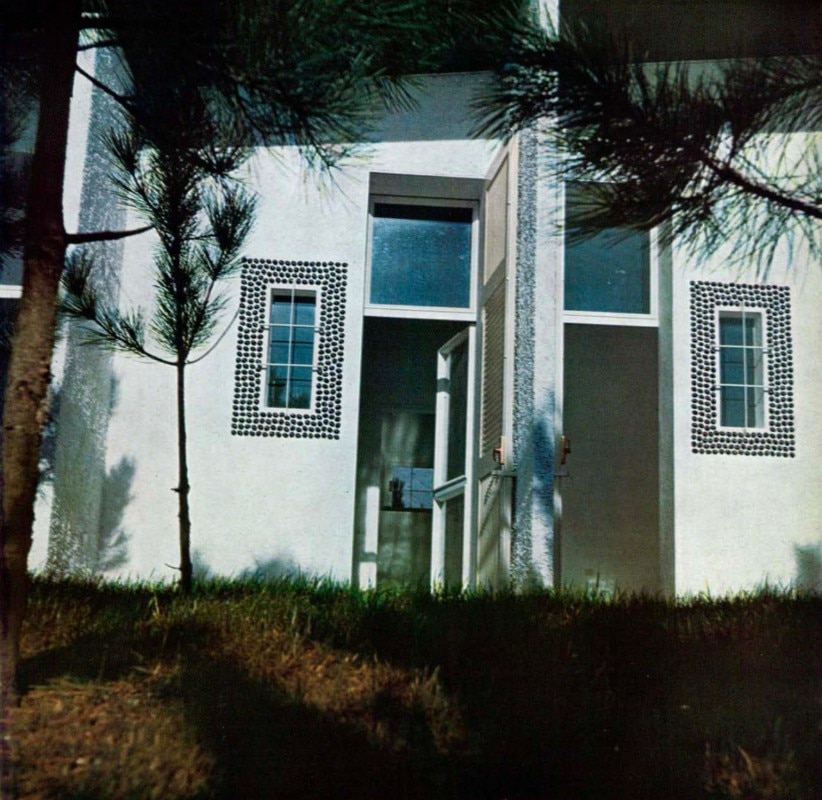

Short introductions, detailed captions and many photographs by Giorgio Casali guide the reader through the transformation of this stretch of coastline. Domus describes the buildings in Arenzano as experiments on integrating architecture into a natural environment, or as devices for observing the landscape through architecture.

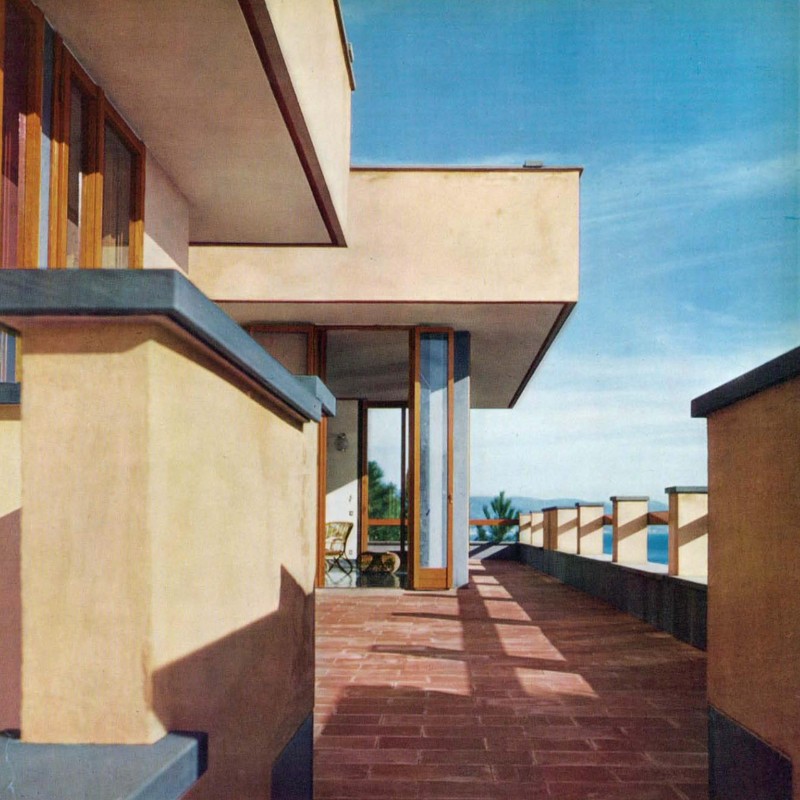

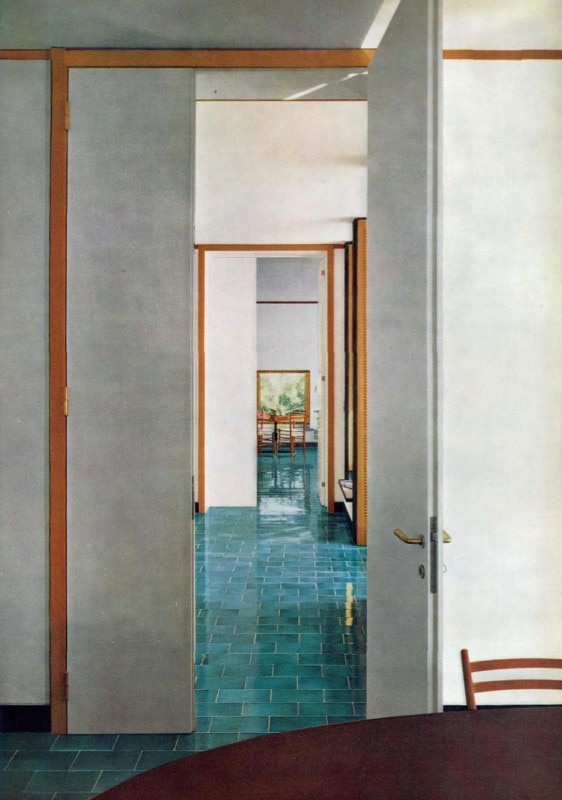

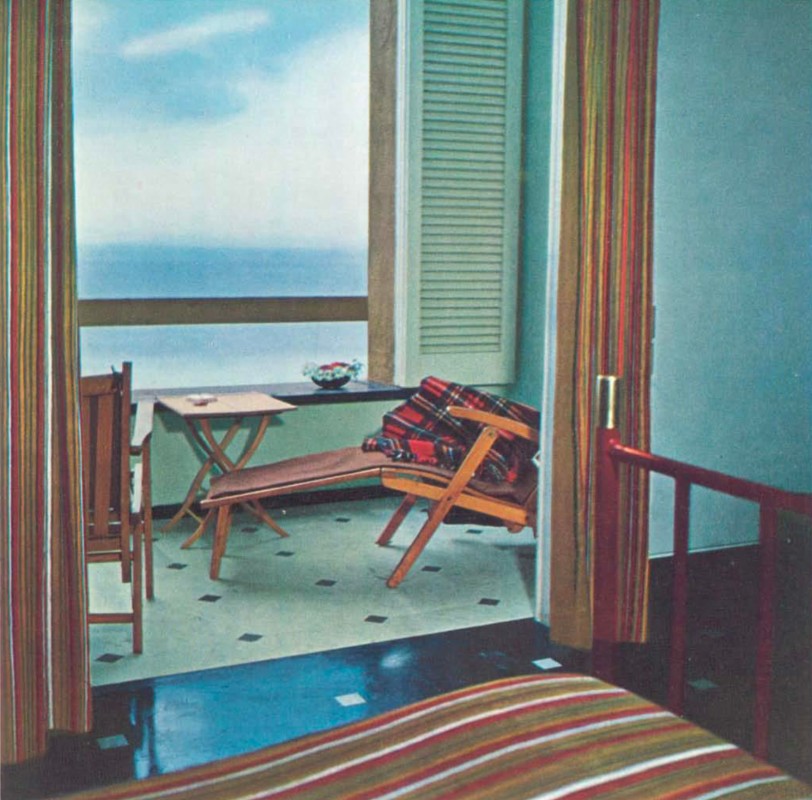

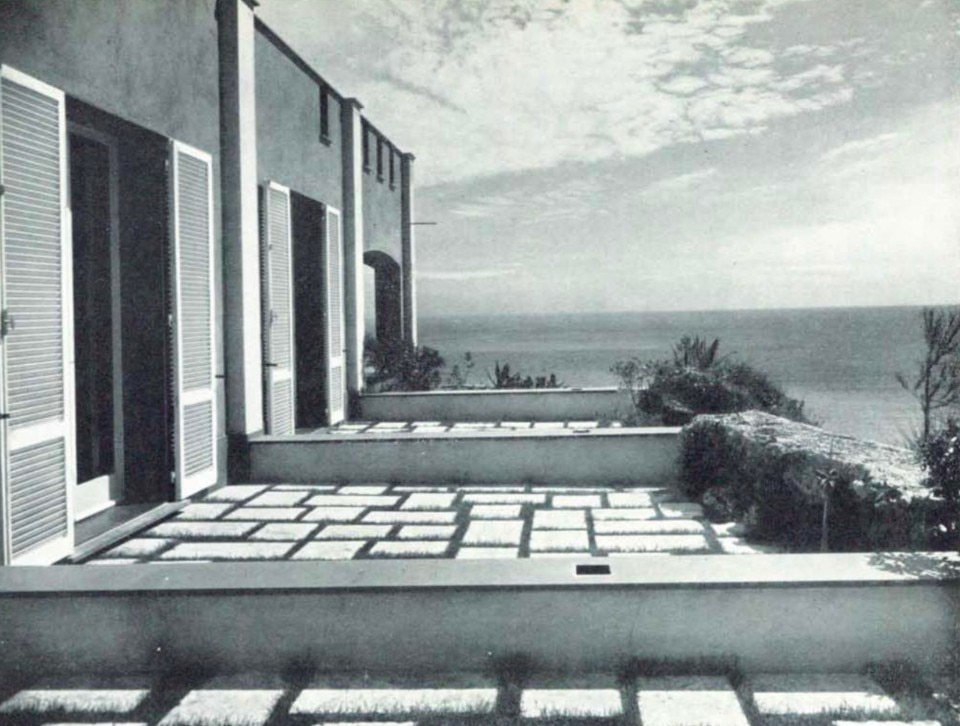

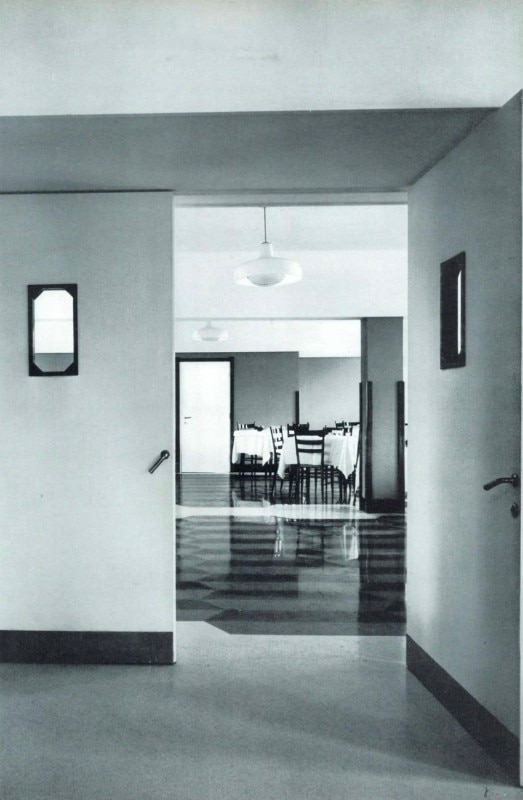

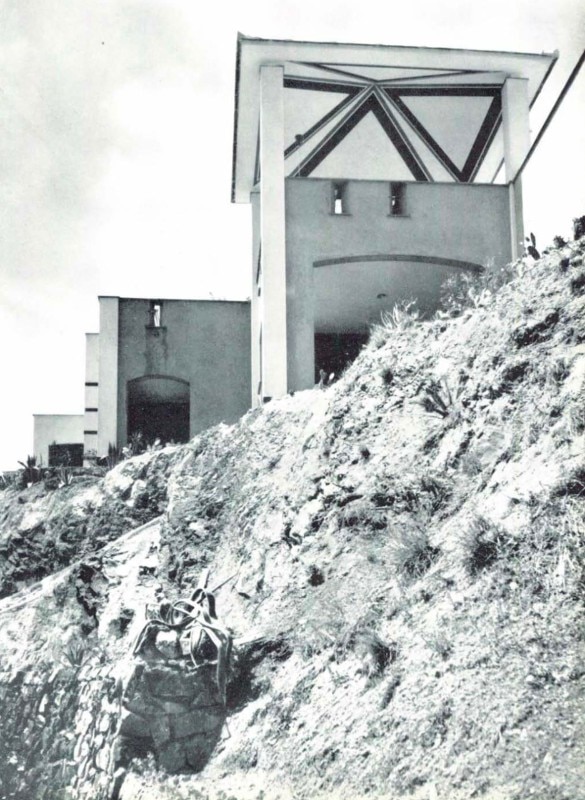

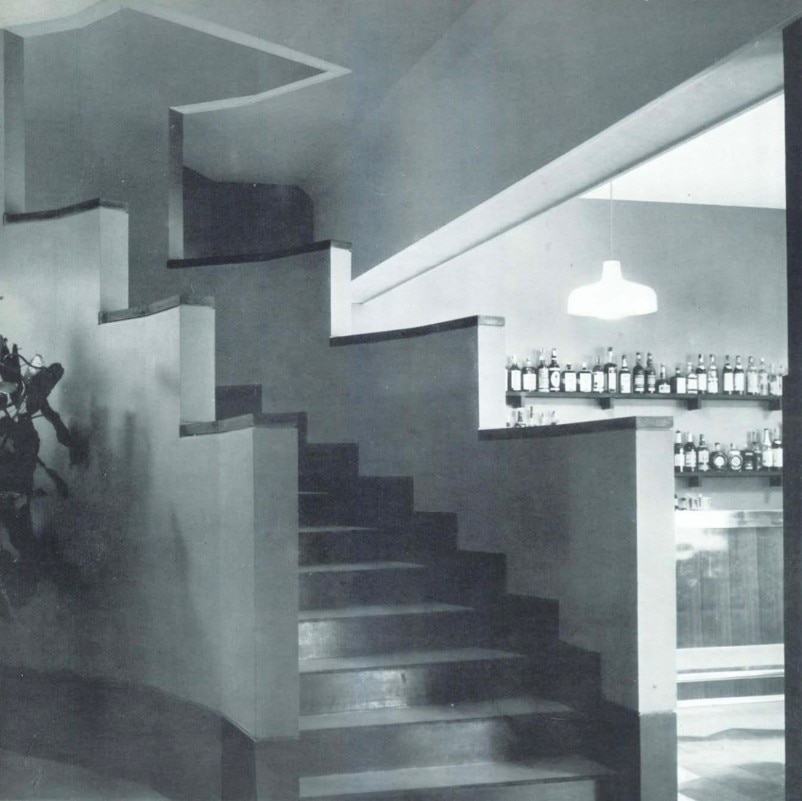

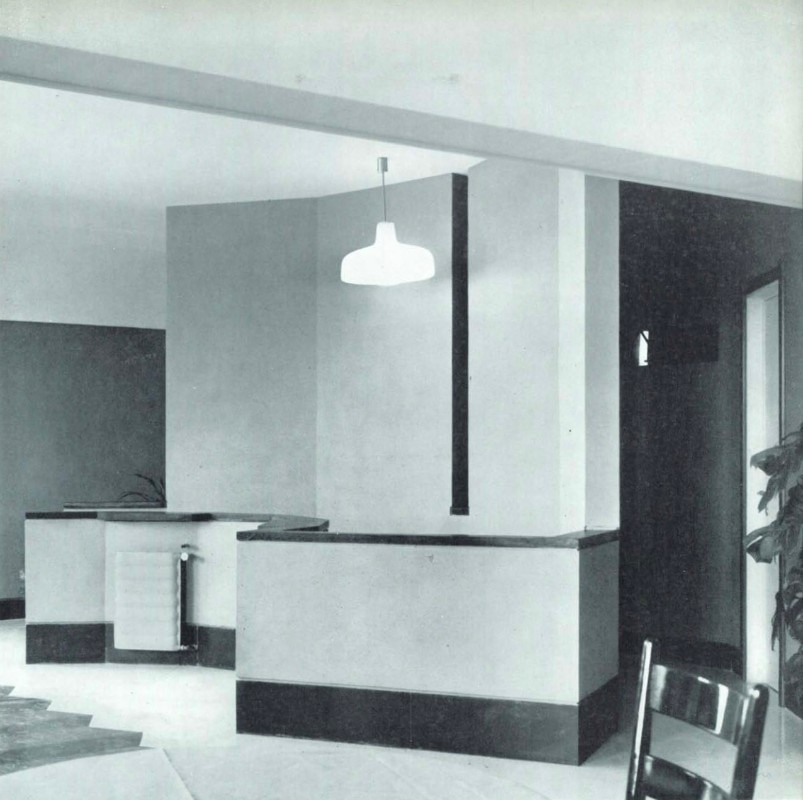

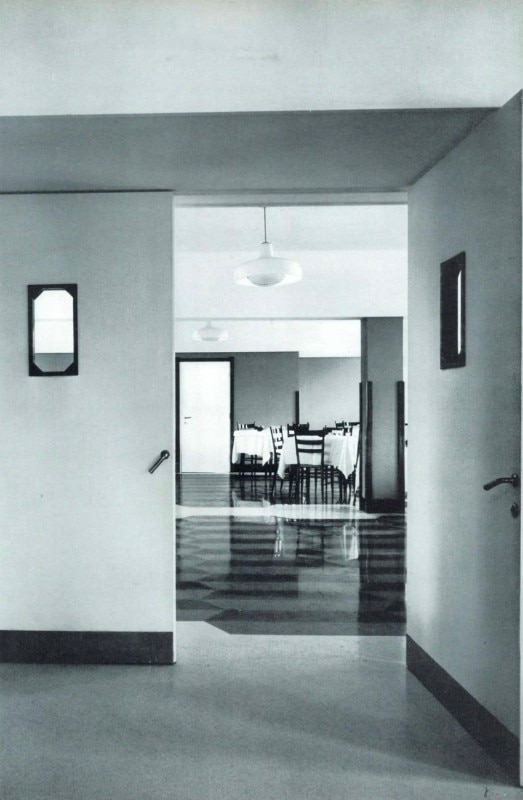

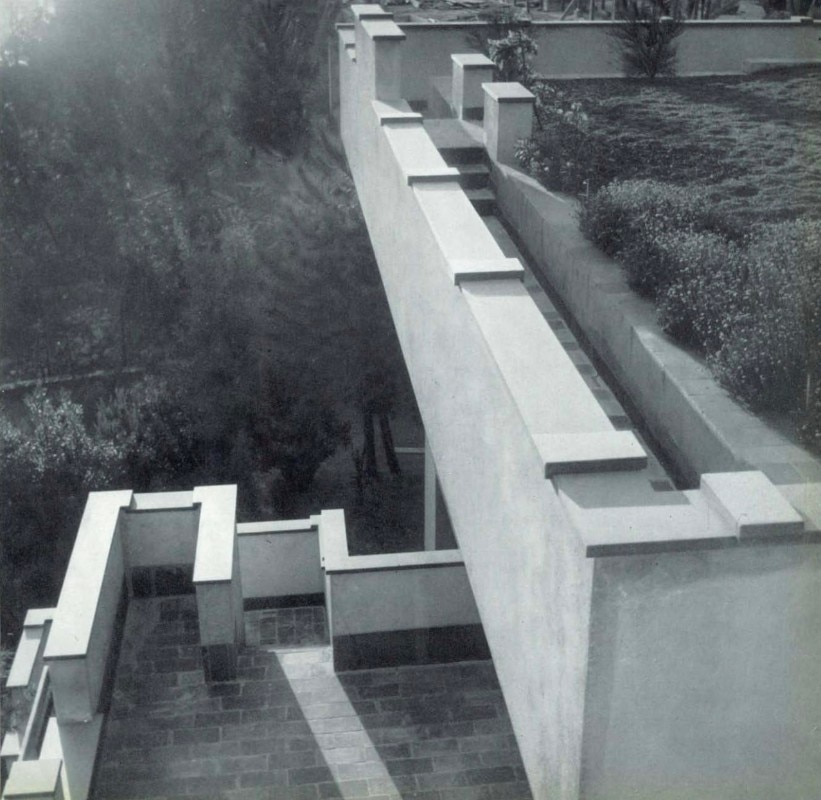

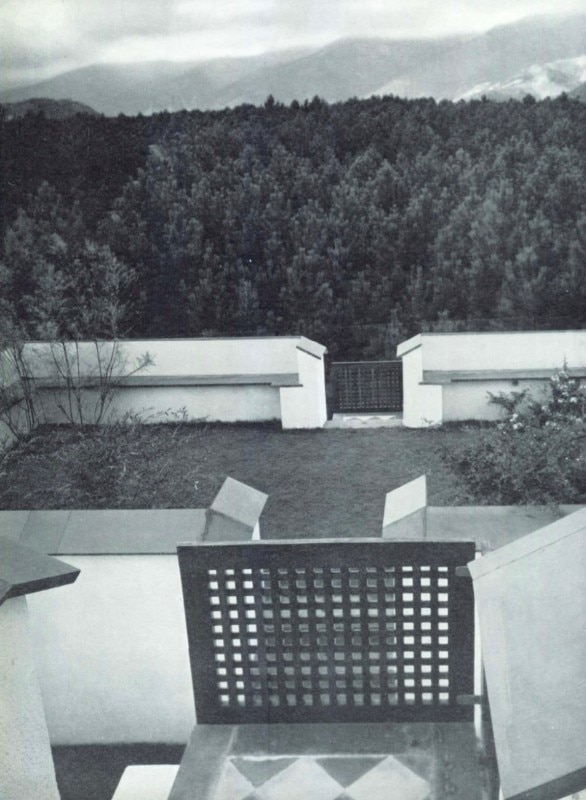

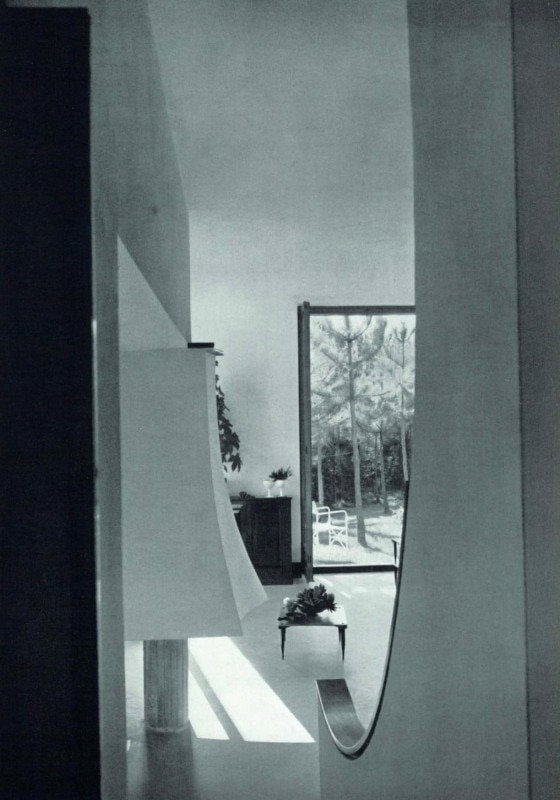

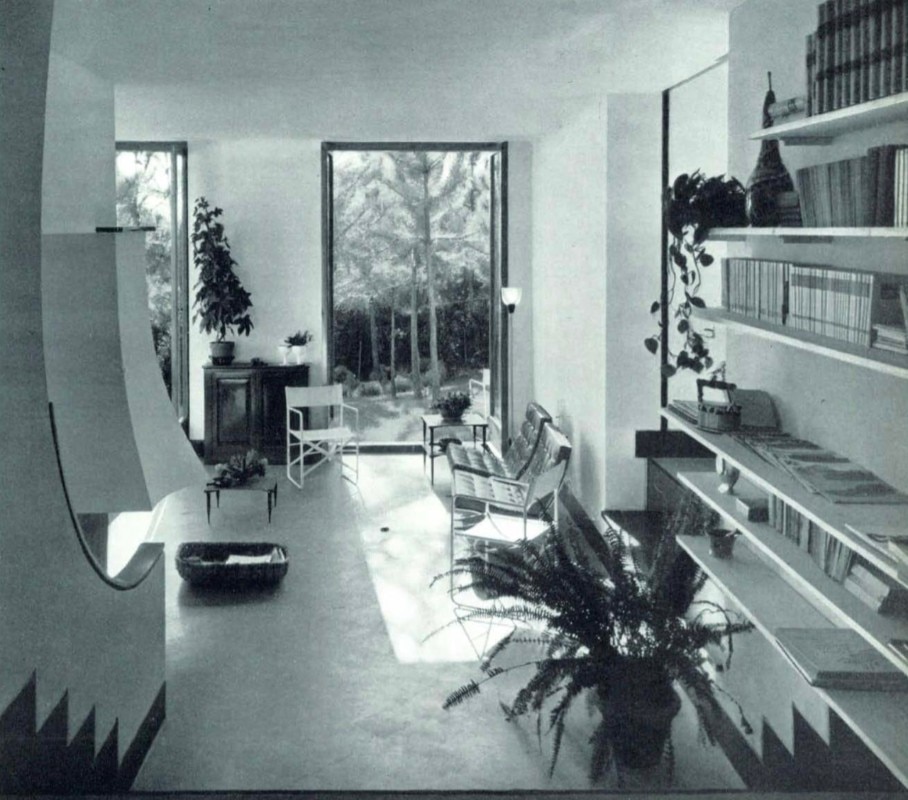

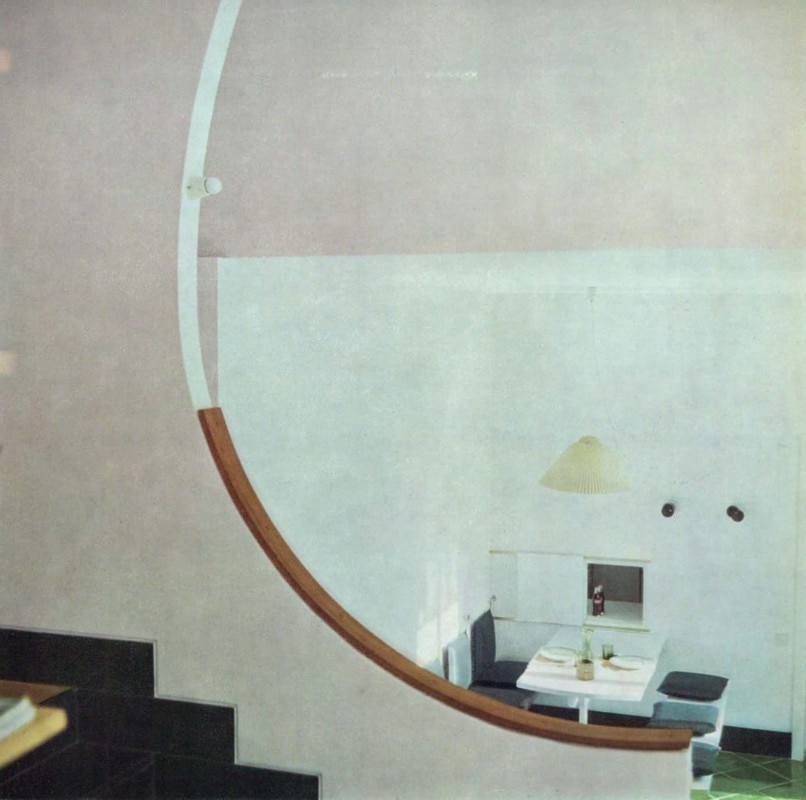

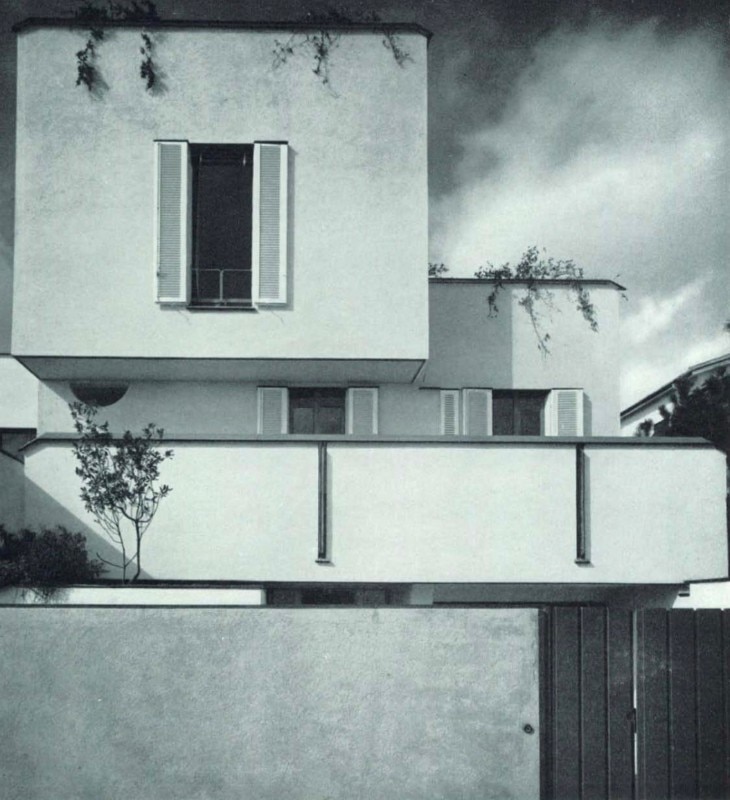

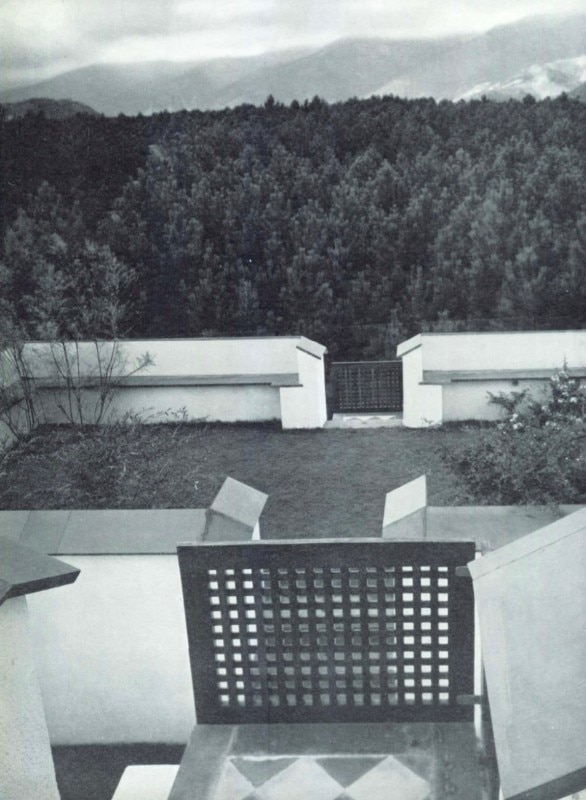

Thus, the hotel in Capo San Martino by Gardella (Domus 344, July 1958) is described as “a lively architectural work that creates a landscape in the landscape: every wall, view and opening is designed to frame in unexpected ways the panorama and the sea, while not being invaded by them”. The square designed by Gardella and Castelli Ferrieri (Domus 369, August 1960) seeks an unconventional relationship with its surroundings, too. The square “does not offer a view of the sea nor of the nearby vegetation. People can only admire the distant mountains to the North. Squares are typically enclosed spaces, but this one is pierced by views that remind us of what is outside: a little glimpse of sky where the buildings do not touch each other; the outline of the mountains beyond the limits of the square”.

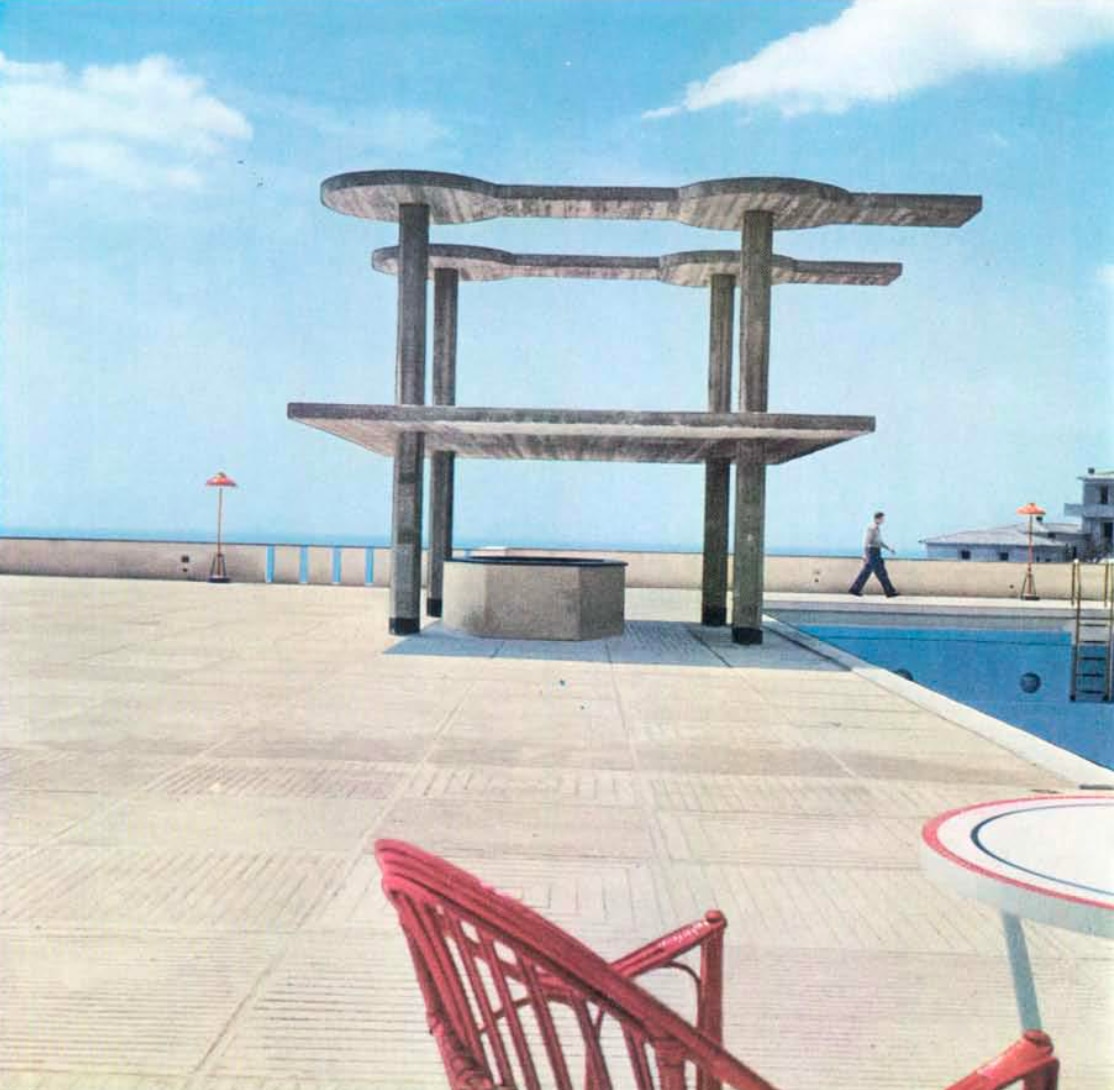

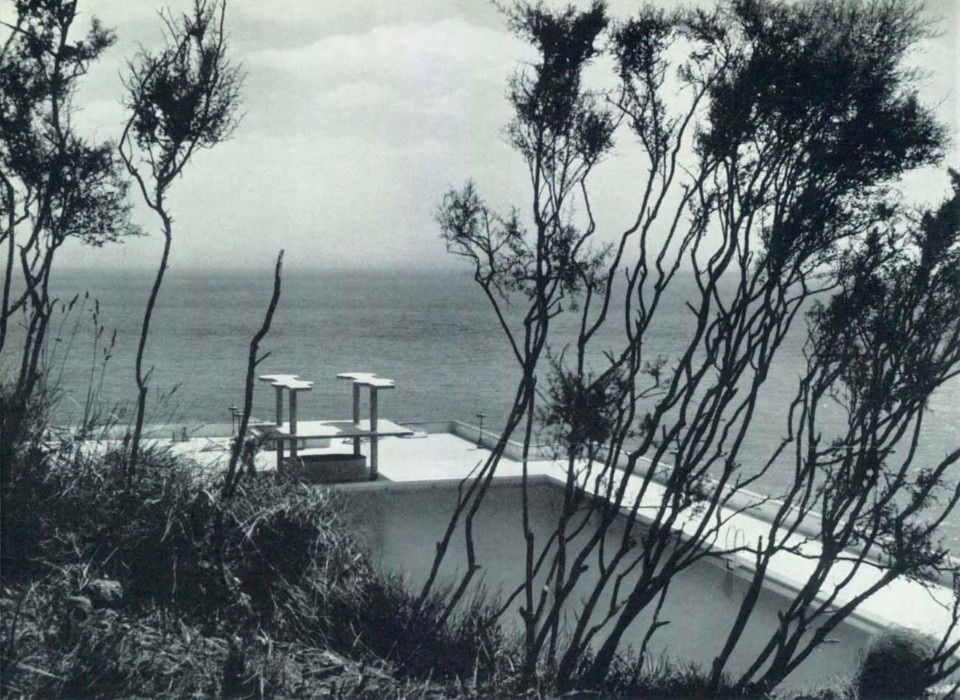

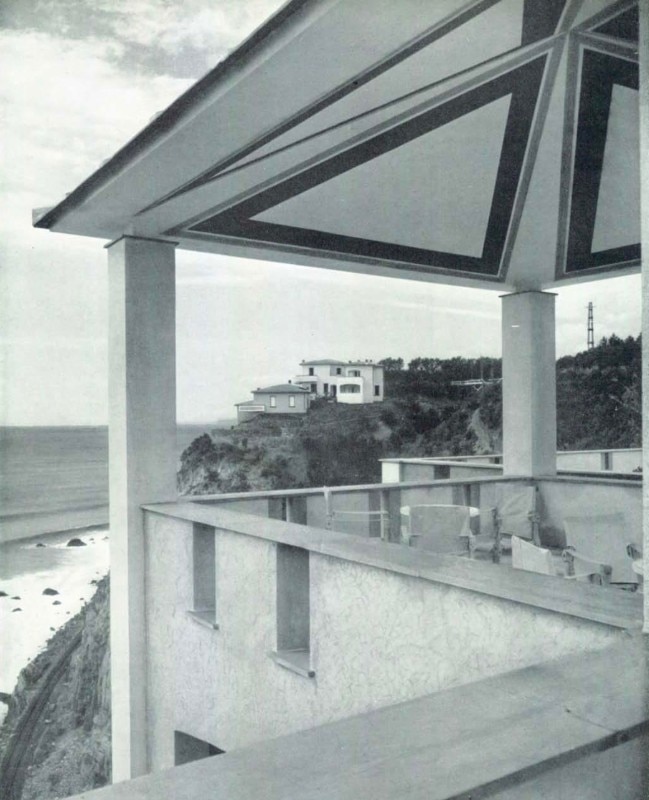

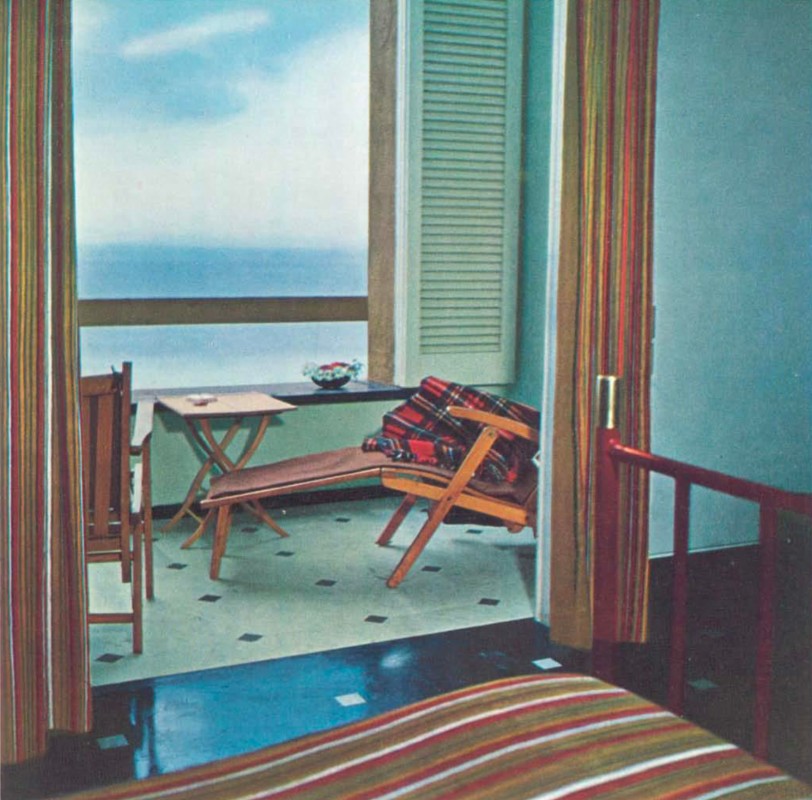

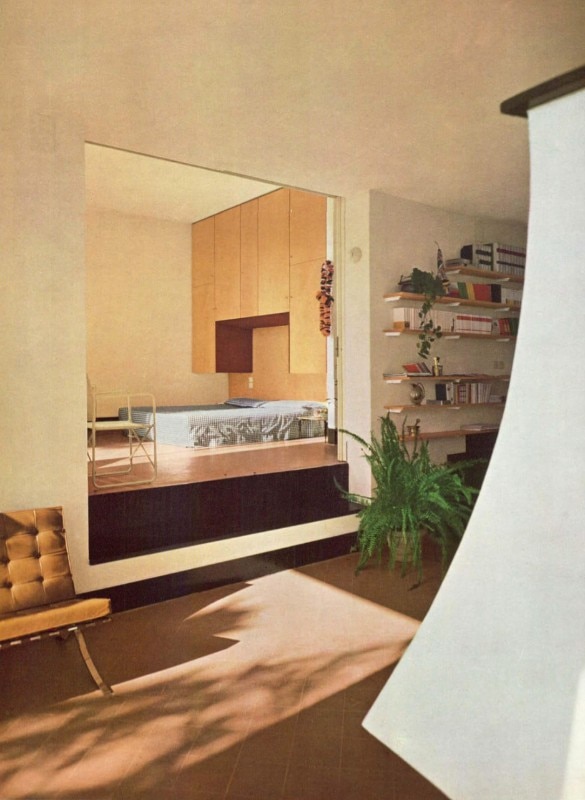

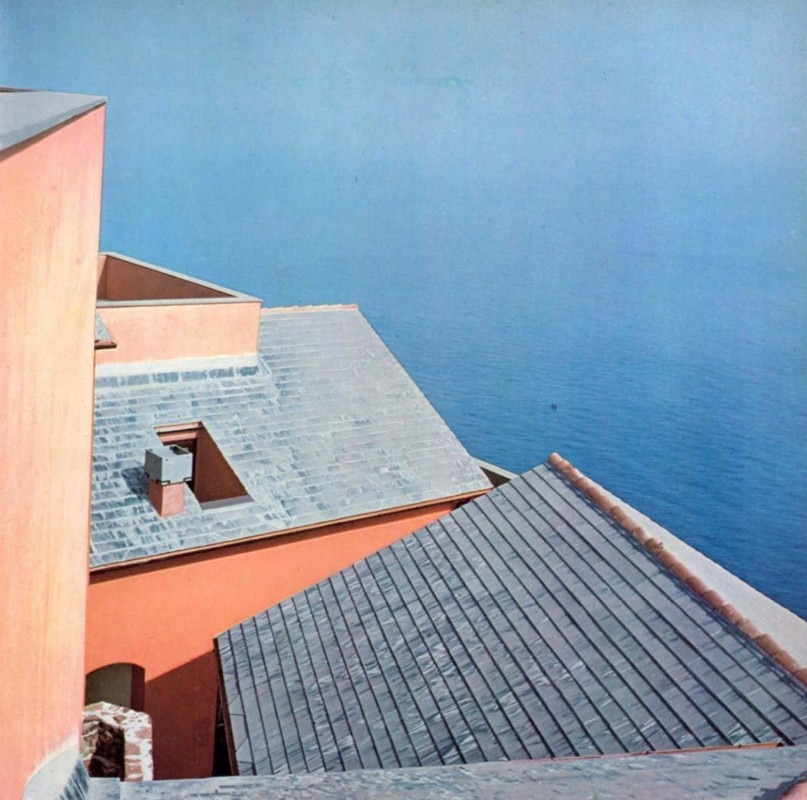

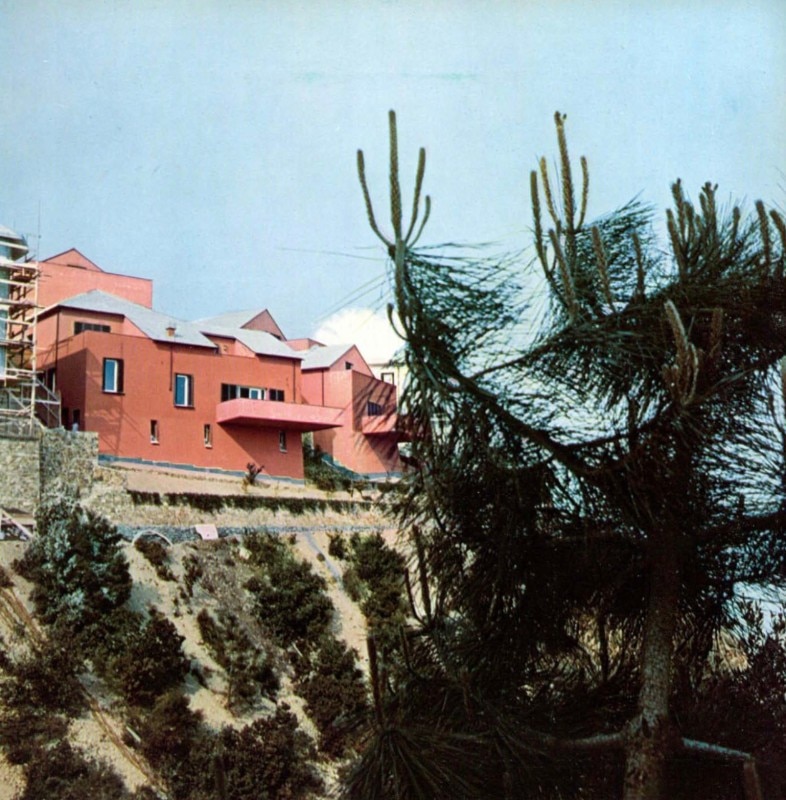

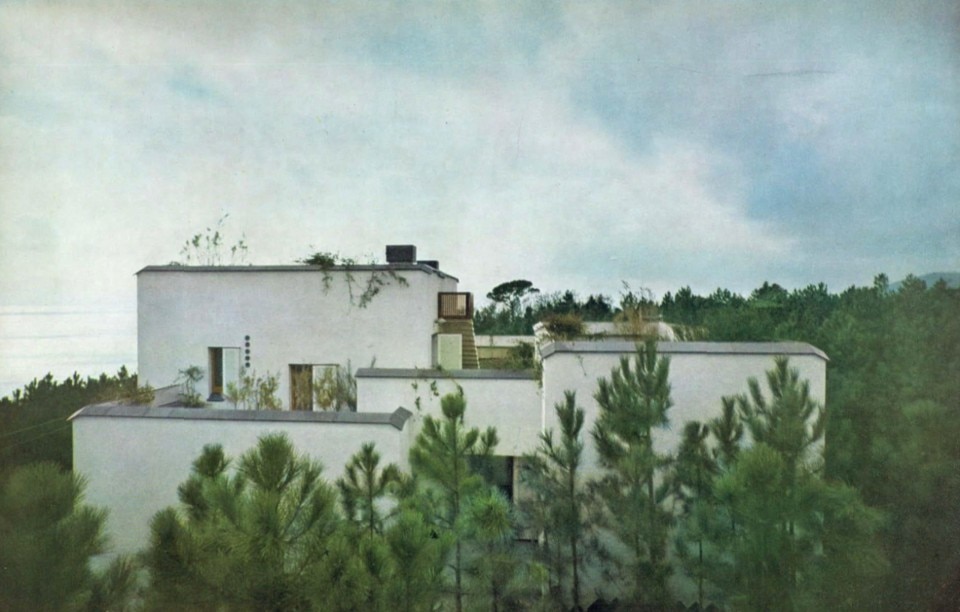

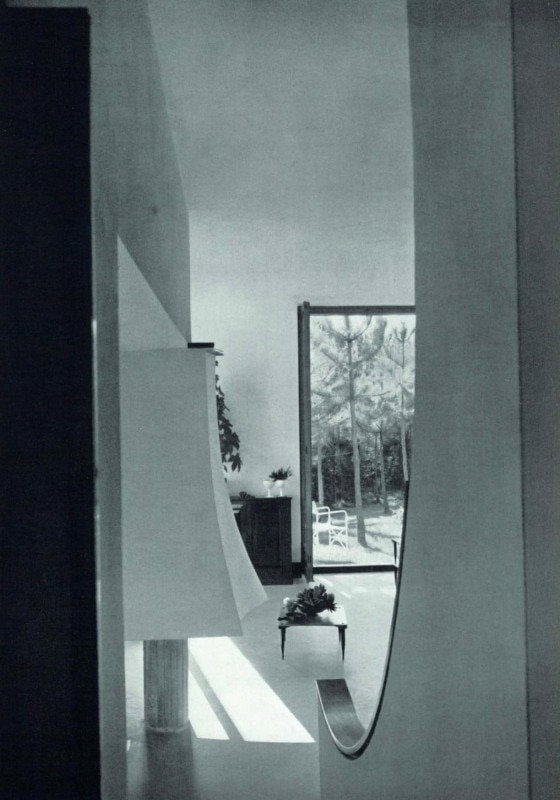

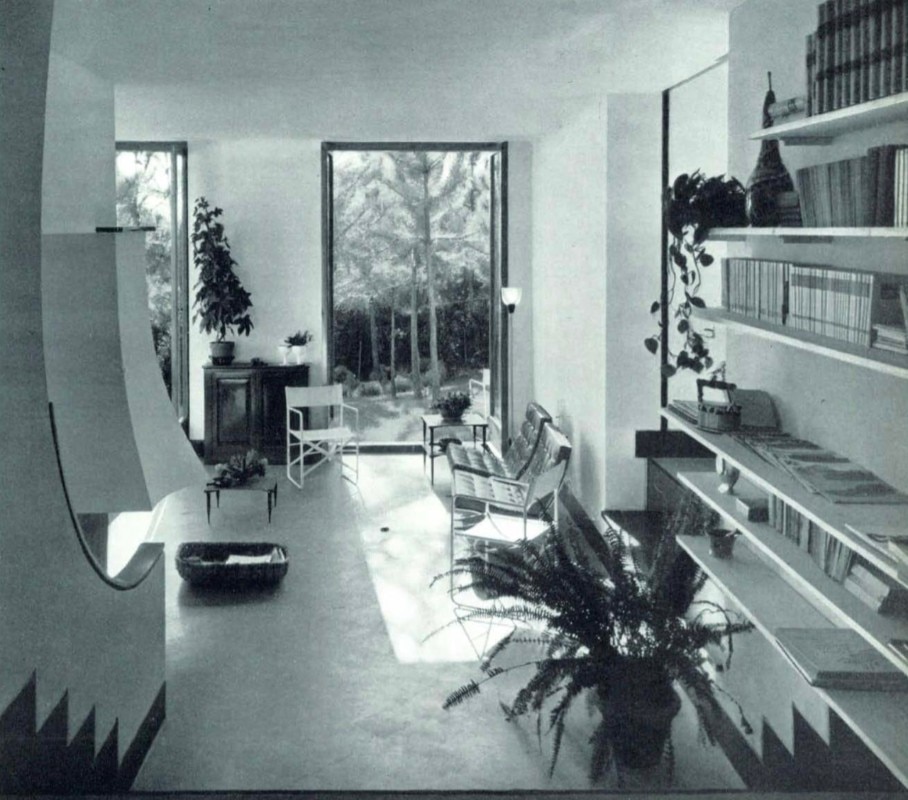

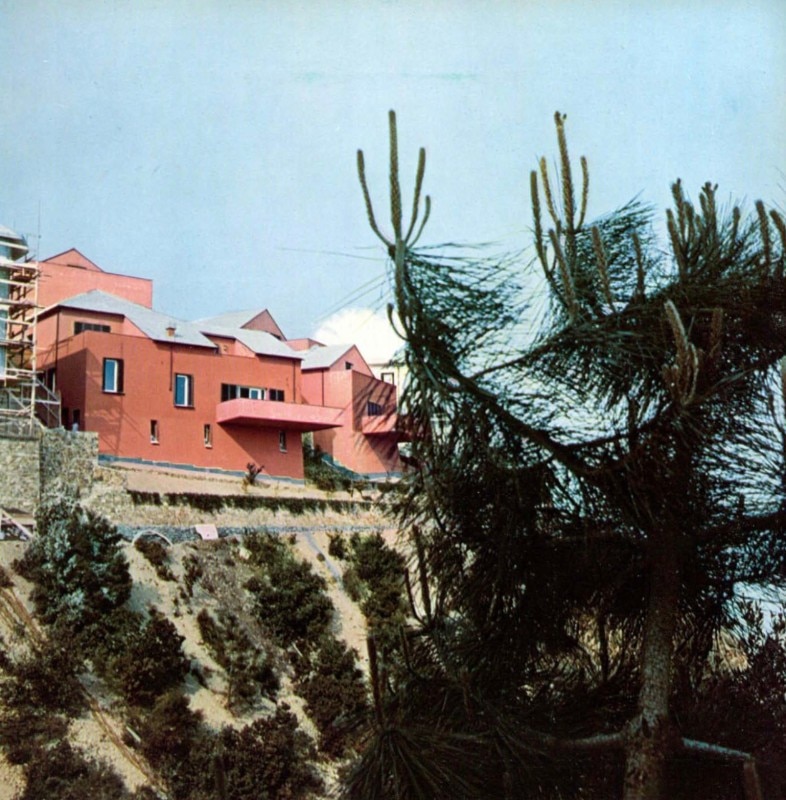

In order to maximise the view over the sea, Ponti’s Villa (Domus 395, October 1962) and Zanuso’s Red Houses (Domus 369) alternate full and empty spaces, screens and openings. Thanks to the many walls of the Villa, observing the landscape becomes a private and personal experience, enjoyable from the living room and the bedrooms. The Red Houses (Case Rosse), on the other hand, are perched on the cliff of the promontory, “towering over the sea, facing it with their closed facades, like buttresses. These two buildings, very complex and close to each other, are separated by narrow and steep ‘carugi’ - Ligurian dialect for passageways.”

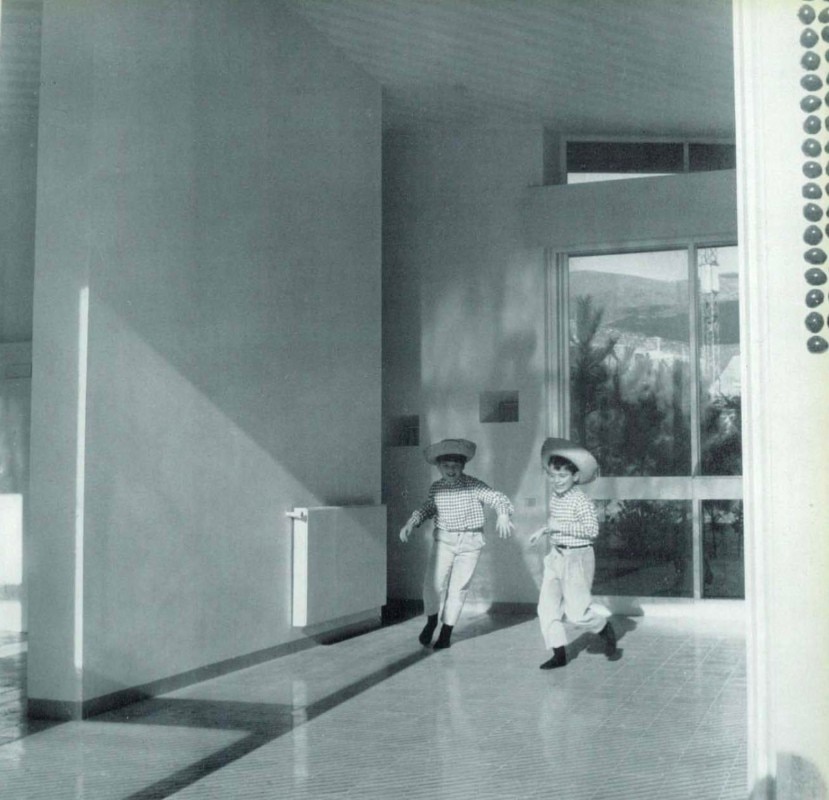

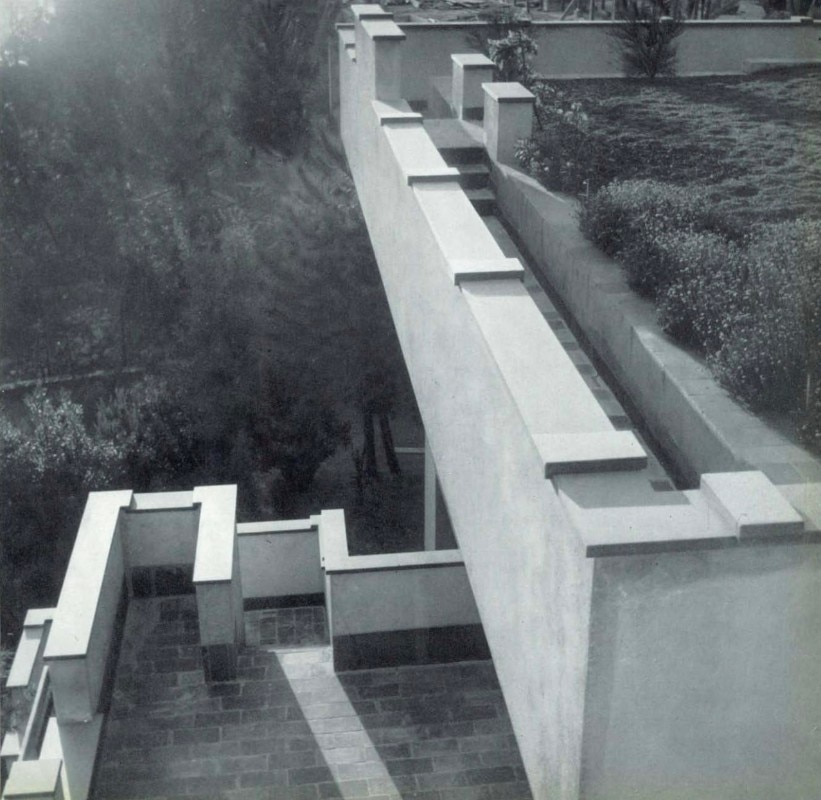

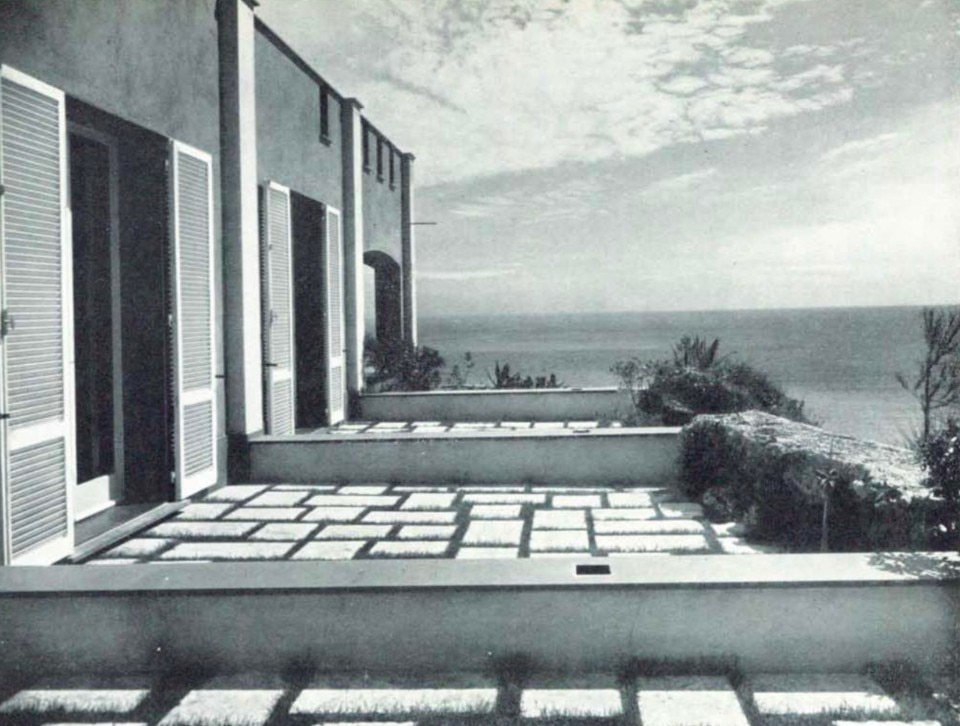

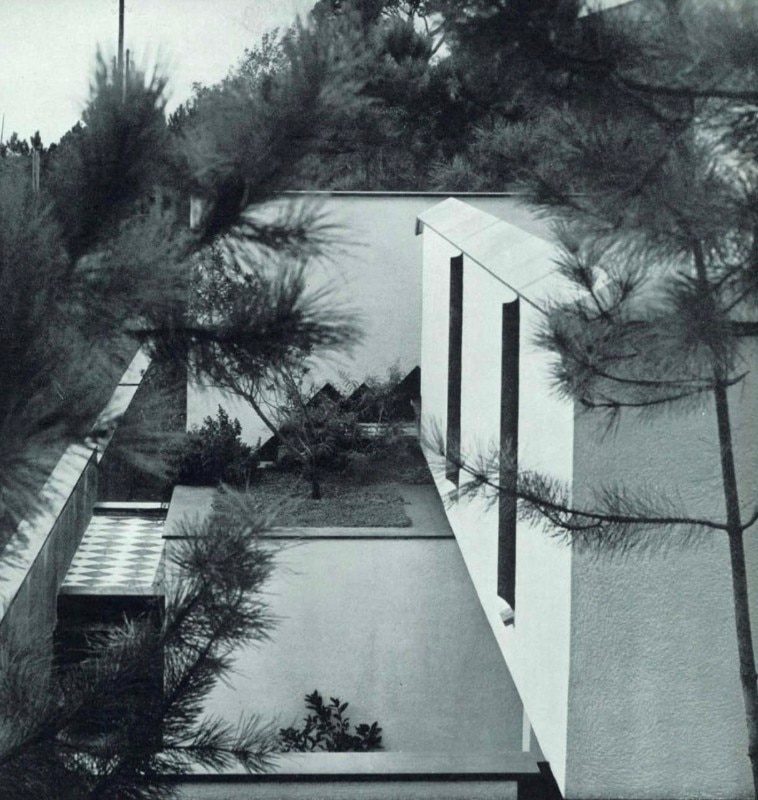

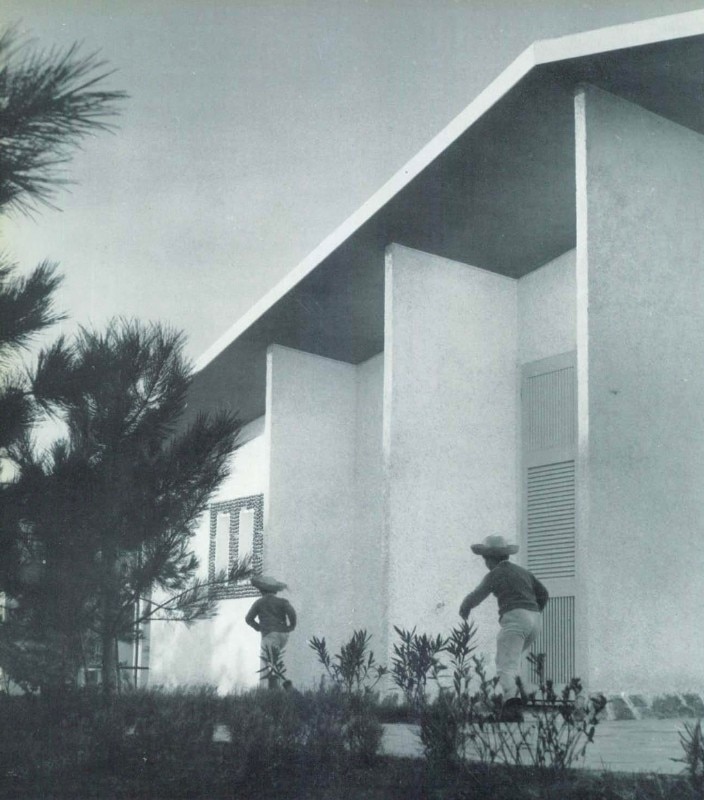

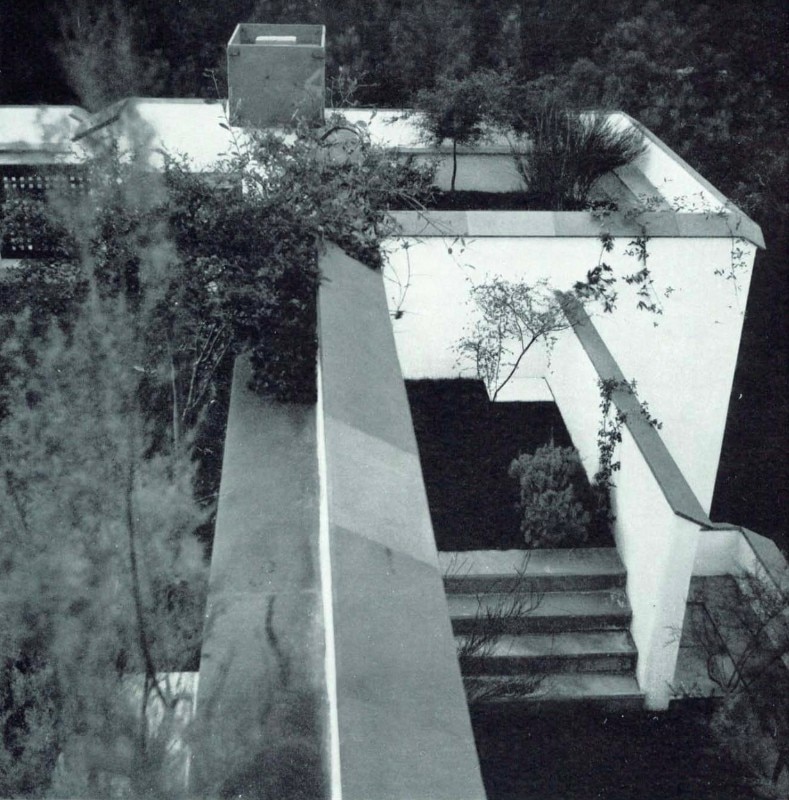

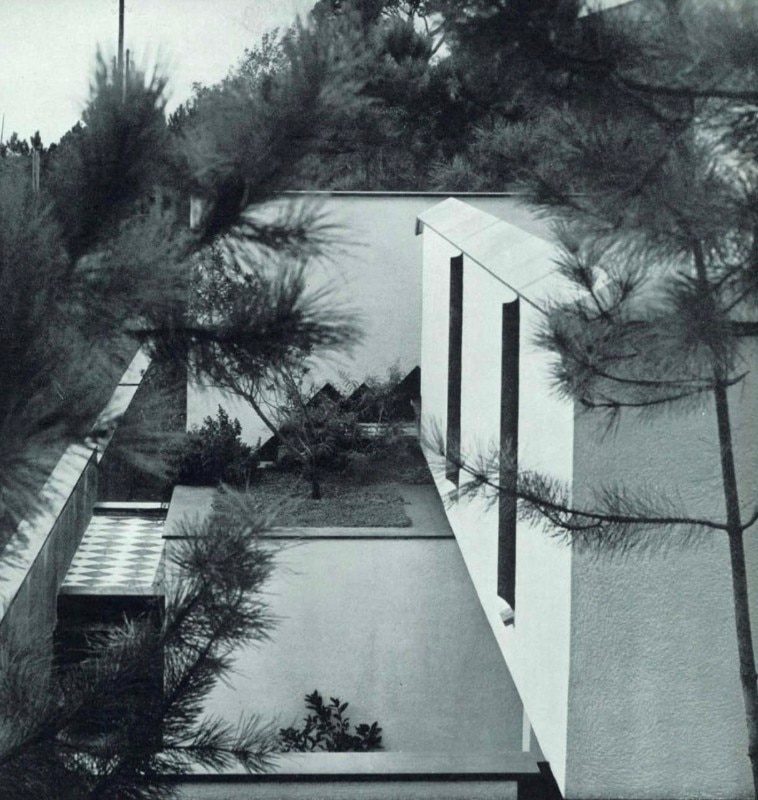

The most outstanding features of the Casa Arosio designed by Magistretti (Domus 363, February 1960) and the Villa designed by Gardella and Castelli Ferrieri (Domus 392, July 1962) are the roof gardens. Magistretti transformed “all the flat roofs (...) into small hanging gardens, communicating with each other and connected, at the bottom, to the ground garden (...). The construction has not eliminated the vegetation: it has lifted it, in some way.” The large roof terrace of Gardella and Castelli Ferrieri is also full of vegetation and equipped for many everyday life activities: “here you can grow flowers, sunbathe (and sandbathe, too), lie down on deck chairs and enjoy the breath-taking view, as if you were on the deck of a ship”. An intelligent solution prevents any obstruction of the view: “in order to prevent the terrace parapet from blocking the view, the perimeter area of the passage has been slightly lowered in relation to the central area of the terrace. As a result, the parapet is only forty centimetres taller”.

View gallery

View gallery

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, piazza, Arenzano, Italia, 1960. Foto Casali-Domus

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

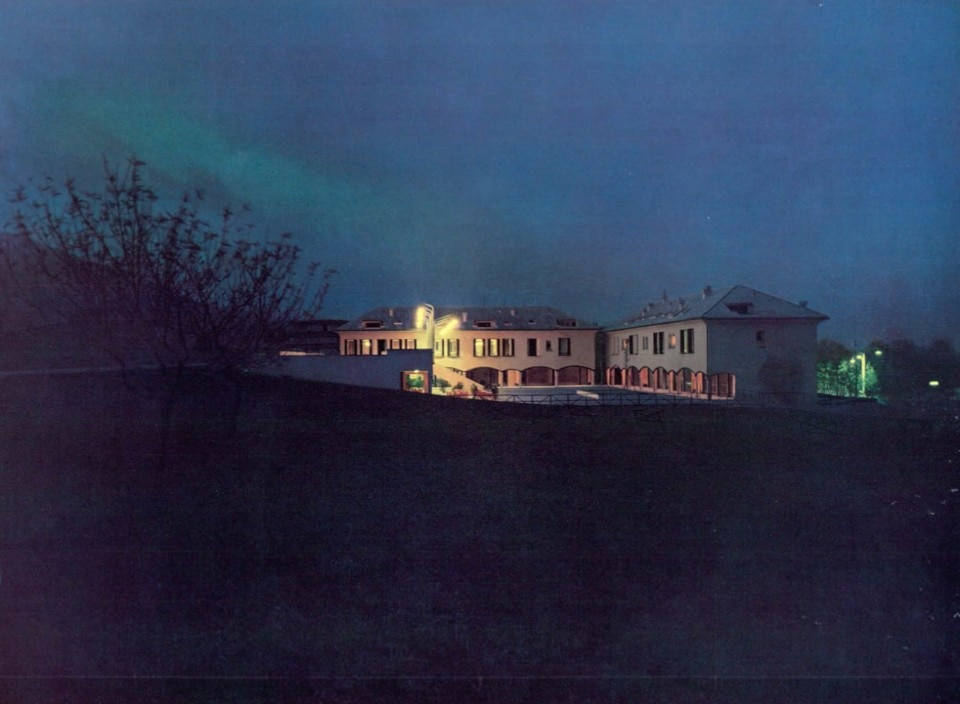

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, hotel in Capo San Martino, Arenzano, Italy, 1958. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

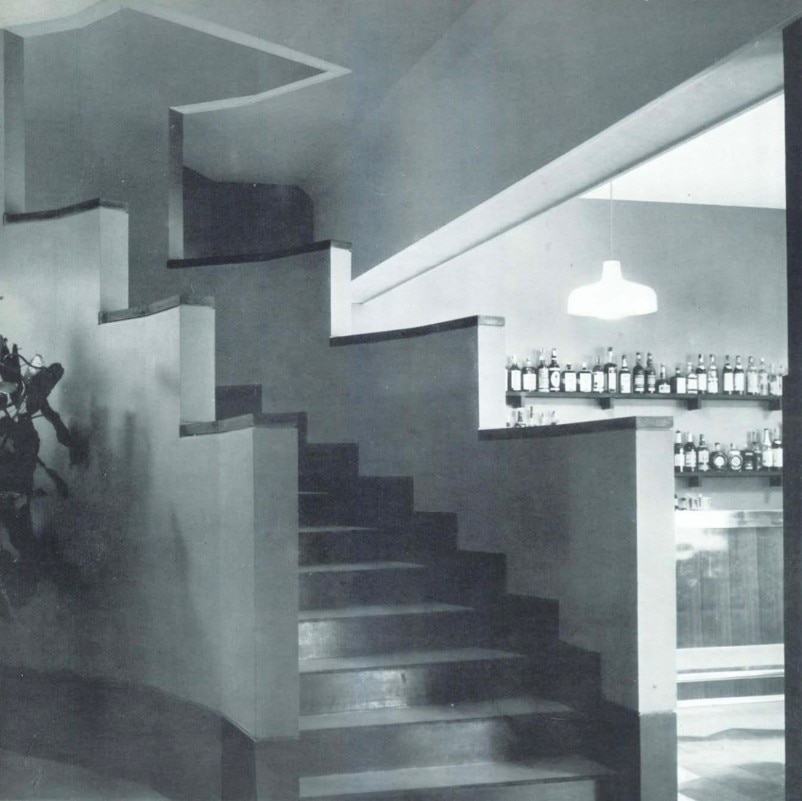

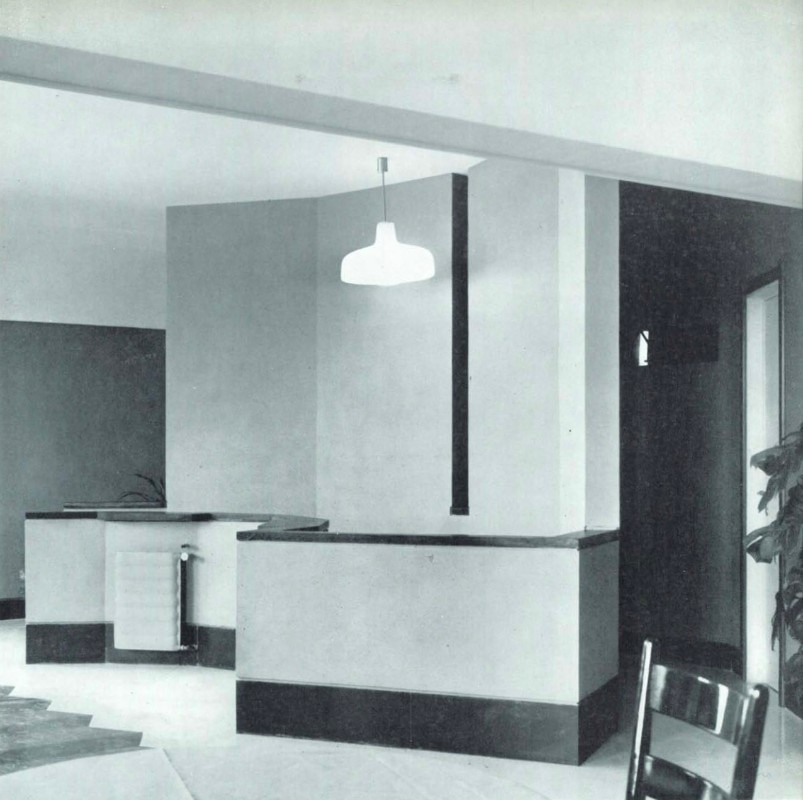

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, piazza, Arenzano, Italia, 1960. Foto Casali-Domus

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, square, Arenzano, Itay, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Ignazio Gardella, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Casali-Domus

“Storia di un’utopia mancata” (“History of a failed utopia”) is the meaningful subtitle of the most famous and complete monograph dedicated to the pine forest, edited by Marco Franzone and Gerolamo Petrone and published in 2010. Arenzano is not only, as Luigi Lagomarsino defined it, an “open-air museum of modern art” which includes the six buildings presented by Domus, but also one of the symbolic places of the descending parable of the construction on the Italian coasts in the second half of the twentieth century. This parable went from the hope of quality (in this case, the heroic beginnings of fine architecture by the Milanese “masters”), then to the explosion of quantity (here, the progressive transgression of the volumetric constraints imposed at first by the property, with a consequent increase in density), and finally to the observation of the destruction of the landscape and the questioning of the cultural premises of coastal urbanization.

Apart from the republication of an article about Ponti’s Villa (Domus 439, June 1966), there had been a substantial press blackout on Arenzano since 1962. But everything changed in October 1977 (Domus 575), when a short but unequivocal quotation, buried in a long article by Massimo Gennari, revealed a radical change of perspective.

View gallery

View gallery

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

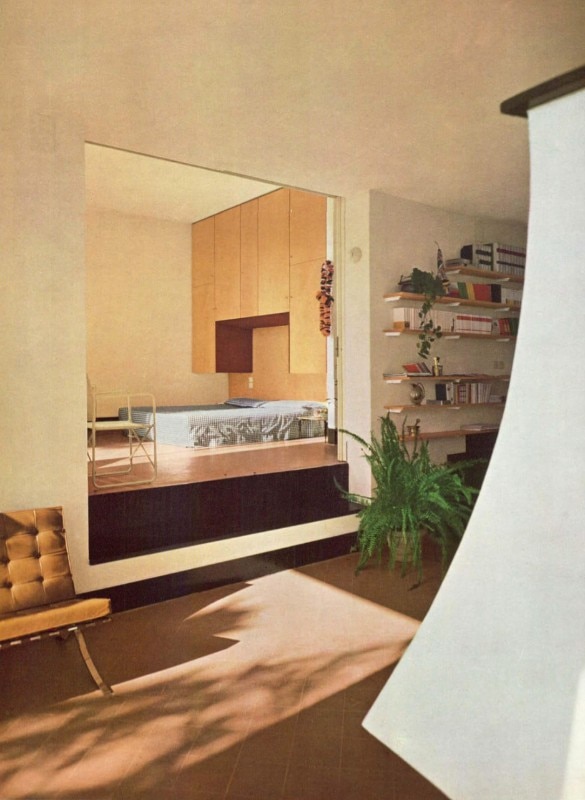

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

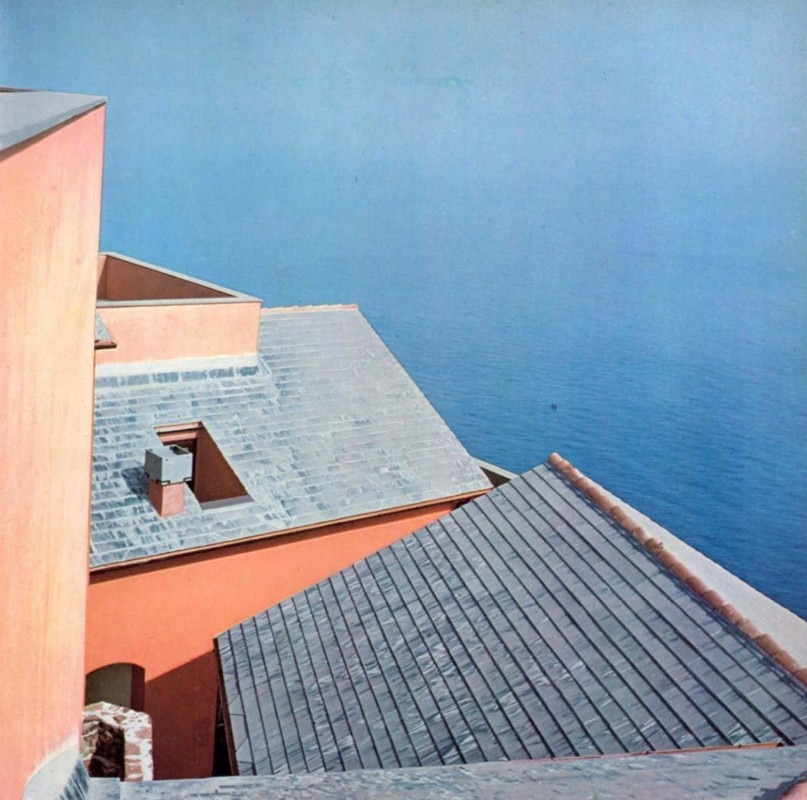

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

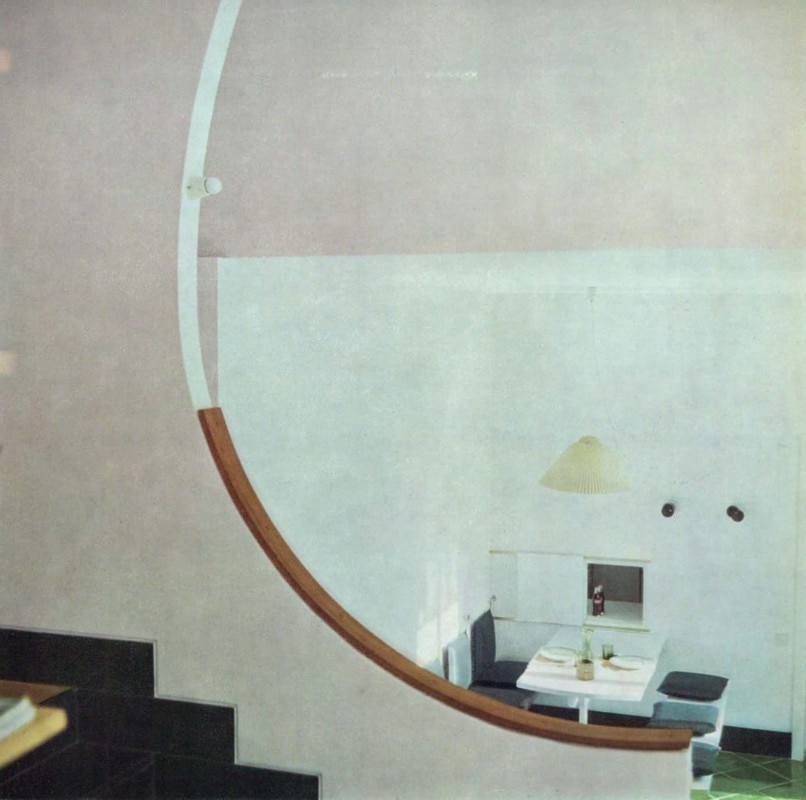

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italia, 1962. Foto Matti

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti , Casa Arosio, Arenzano, 1960. Photo: Casali-Domus. In Domus 363, February 1960.

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Vico Magistretti, Casa Arosio, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Marco Zanuso, Red Houses, Arenzano, Italy, 1960. Photo Casali-Domus

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italia, 1962. Foto Matti

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Arenzano: wonders and contradictions of an acropolis by the Ligurian Sea

Giò Ponti, villa, Arenzano, Italy, 1962. Photo Matti

Gennari, focusing on the ideologies and methodologies of the recovery of Italian historical centres, considered the city and the territory not as artistic facts, but as the political and social reality in which architecture and urbanism intervene. The dynamic of “tourist colonization” of the coasts during the two previous decades is condemned without appeal, and with it the experience of the Milanese enclave in Liguria. “It is sufficient to have a look at one of the many ‘studies’ commissioned by private and public bodies on new tourist-residential locations.”, says Gennari, “You will find an unedifying chapter (...) in the history of contemporary architecture: Arenzano and Donoratico, Piani d'Invrea and Capo Stella, Punta Ala and Migliarino (...) are above all a new tool for the disarticulation of the historical and social fabric. This way, any functional link between the territorial settlement system and the corresponding productive structure is definitively disrupted”.

It is time to put the role of architecture into a broader perspective of virtuous use of the territory. Arenzano’s “utopia” opens up to a more complex interpretation, which evolved during the following decades, capable of recognizing its merits (the exceptional quality and experimentation of its best buildings), as well as its limits and deformations (the privatization of the landscape, that went from being a common good to a profit and enjoyment of a limited elite).