Your practice works on all sorts of projects but you seem to find infrastructures the most challenging. How did this interest arise?

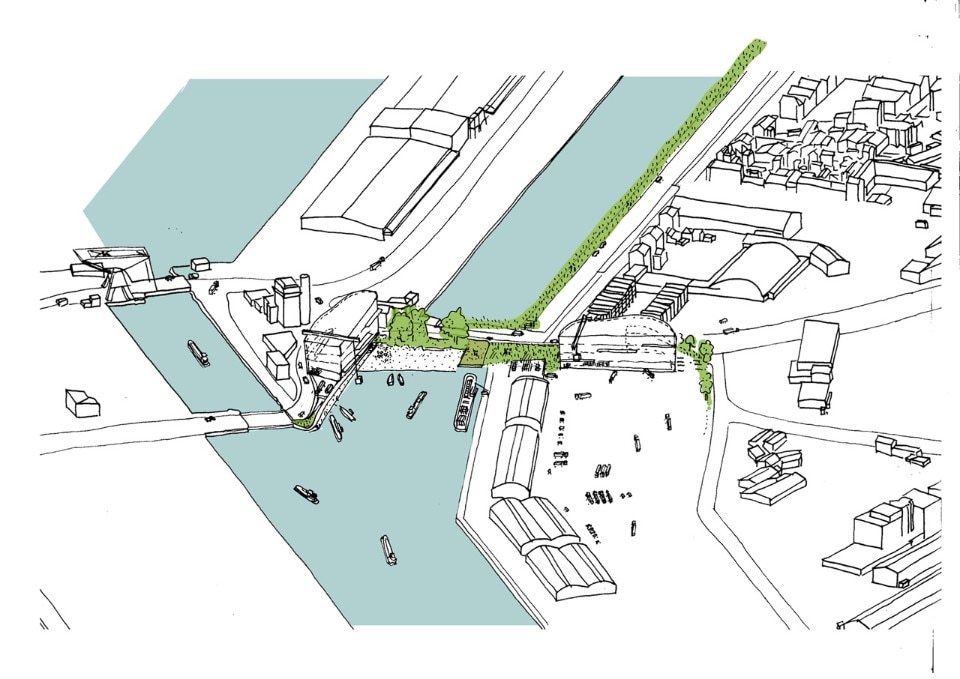

We founded TETRA Architecten in 2009, when the four partners (Ana Castillo, Lieven De Groote, Jan Terwecoren and Annekatrien Verdickt) signed up for a competition to design a new visitor centre for the port of Ghent. TETRA won the competition and built the visitor centre. The analysis we conducted at the port of Ghent back then laid the foundations for our interest in urban infrastructures. We believe the accommodation of logistic and industrial activities in the contemporary city is becoming increasingly significant for future urban developments. The role of these activities is vital to sustaining the success of a city’s economy. They provide many jobs and services every day. Utilities, waste, recycling and distribution are indispensable within the city and proximity is vital for efficient operations and transport.

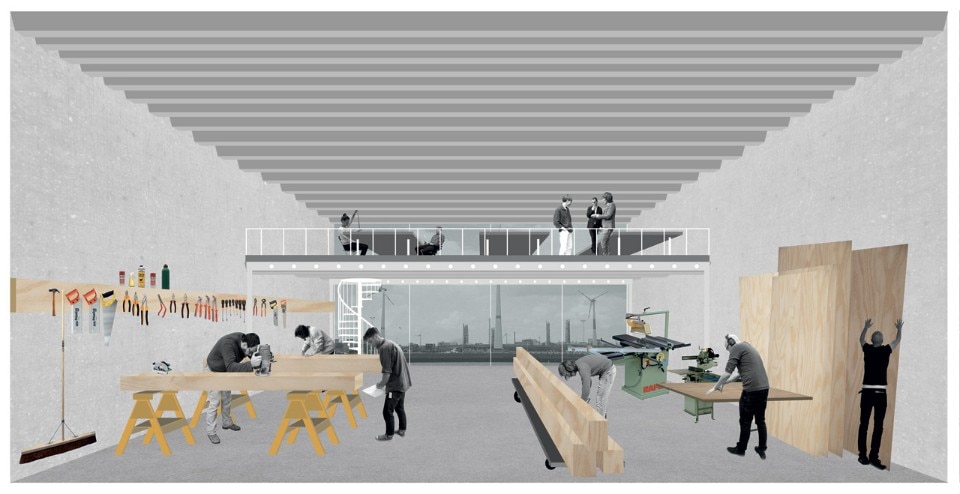

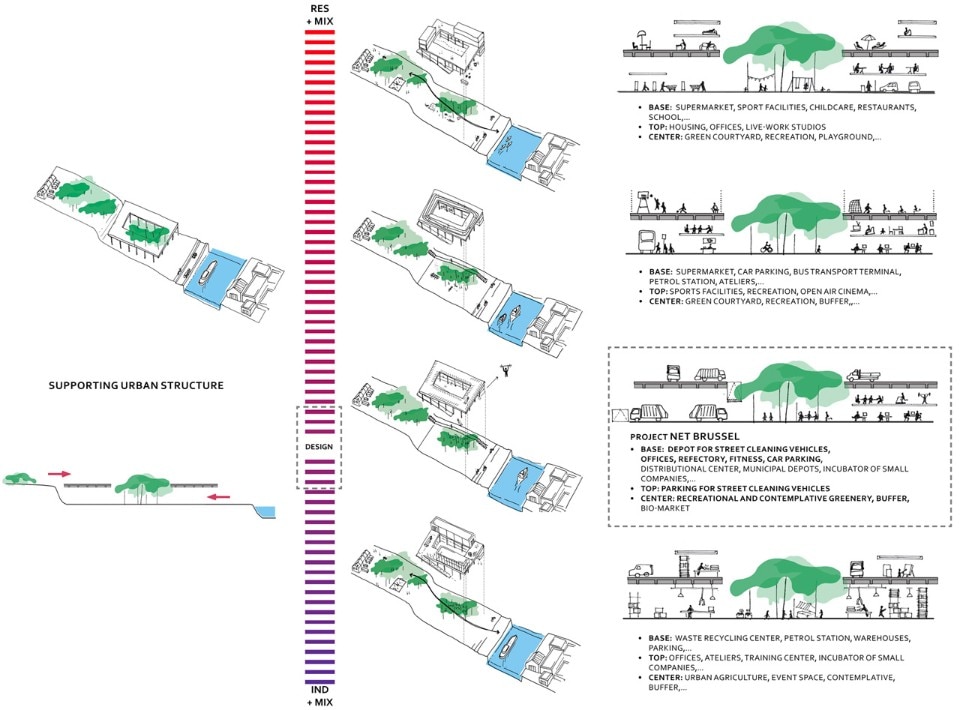

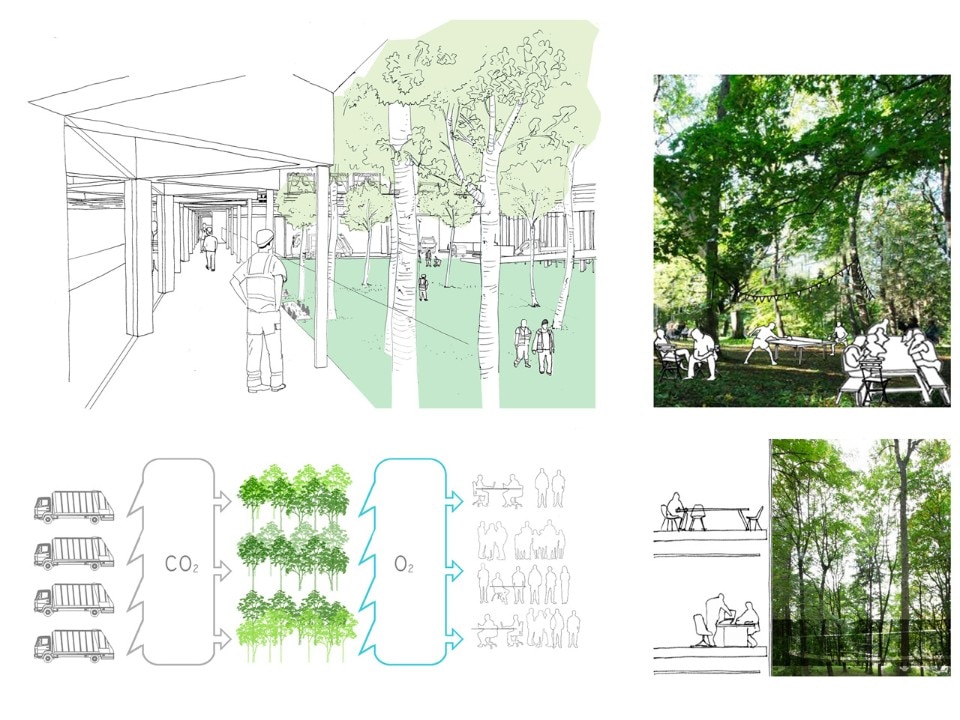

Governments and companies in the sector are aware of the need for new approaches to the physical accommodation of logistic and industrial activities because traditional development patterns are unsustainable. As demand for housing grows and land supply becomes increasingly constrained, we are faced with the need to cohabit with new urban strategies. Many companies take this challenge as an opportunity to improve the unfamiliar (and often negative) image citizens have of logistics and industry. By making their activities visible, citizens are more involved in the workings of the city. Architecture becomes an important factor in this new context. The anonymous warehouse must make way for quality and integrated architecture.

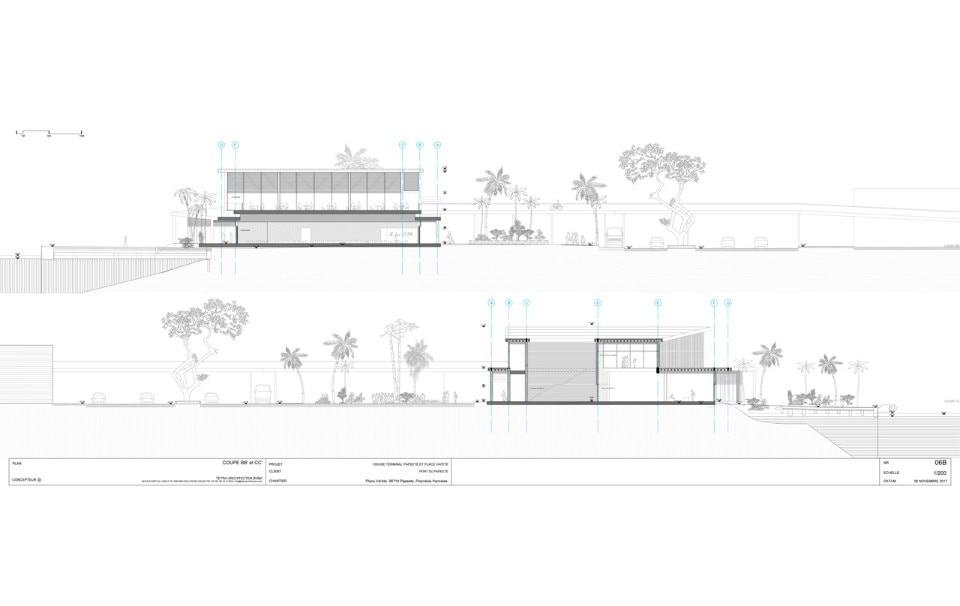

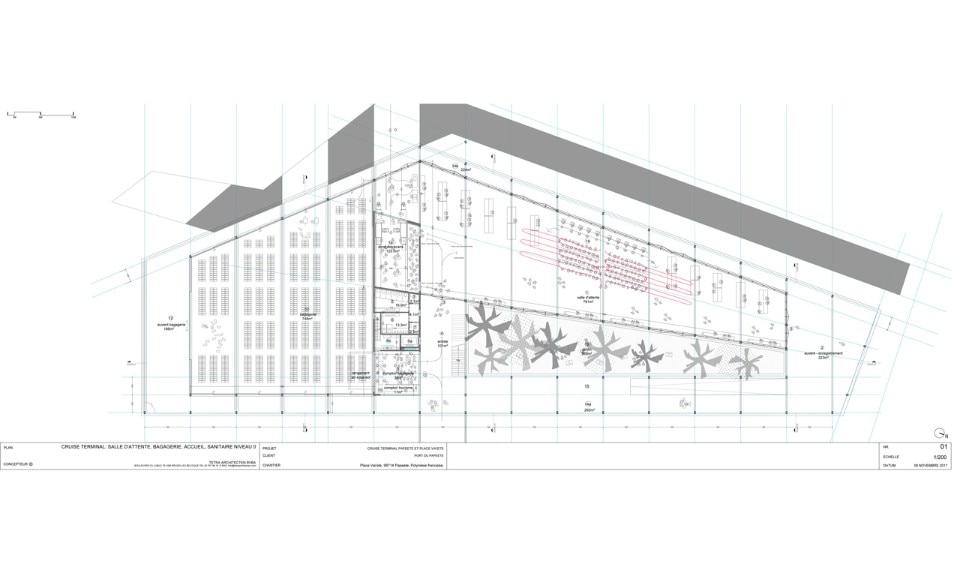

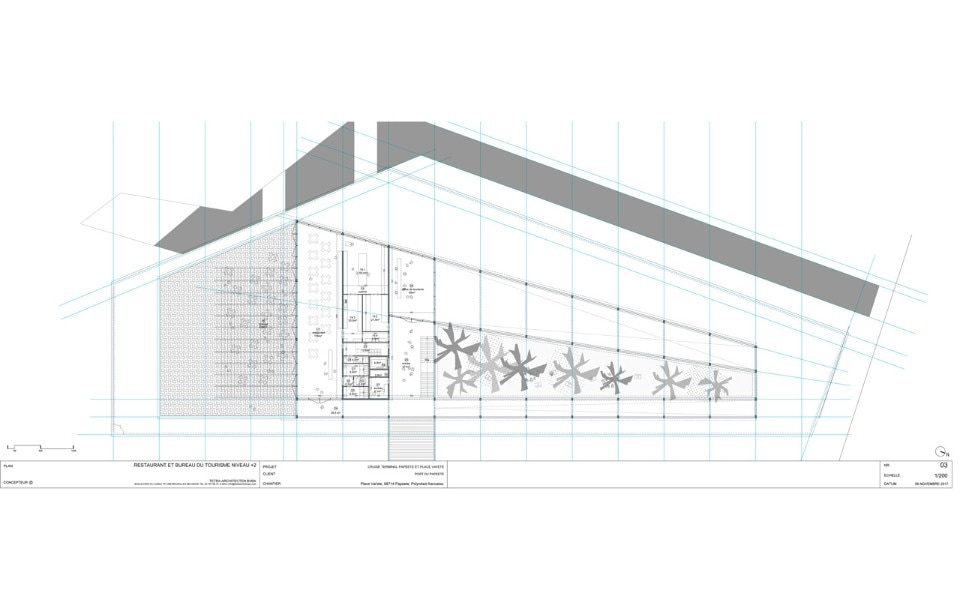

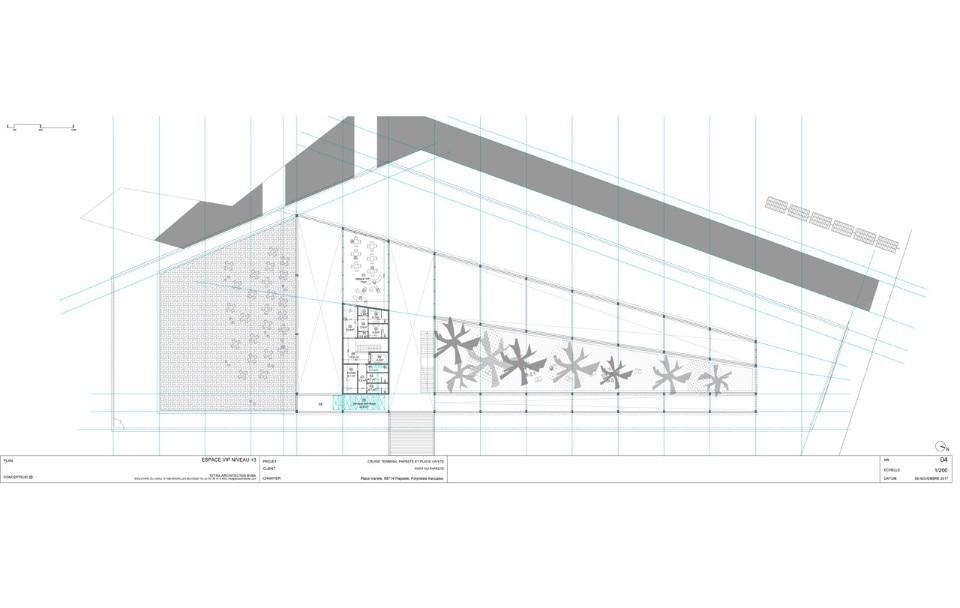

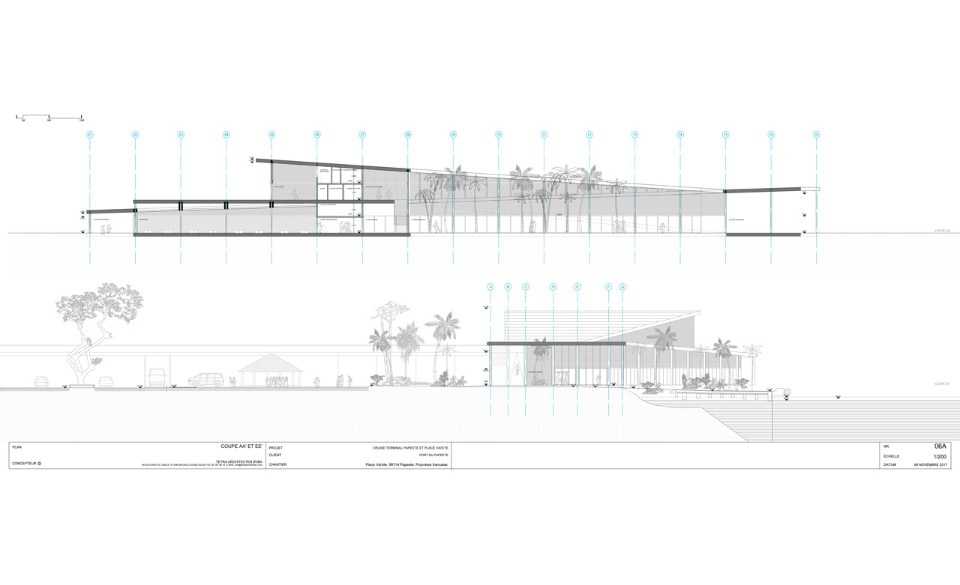

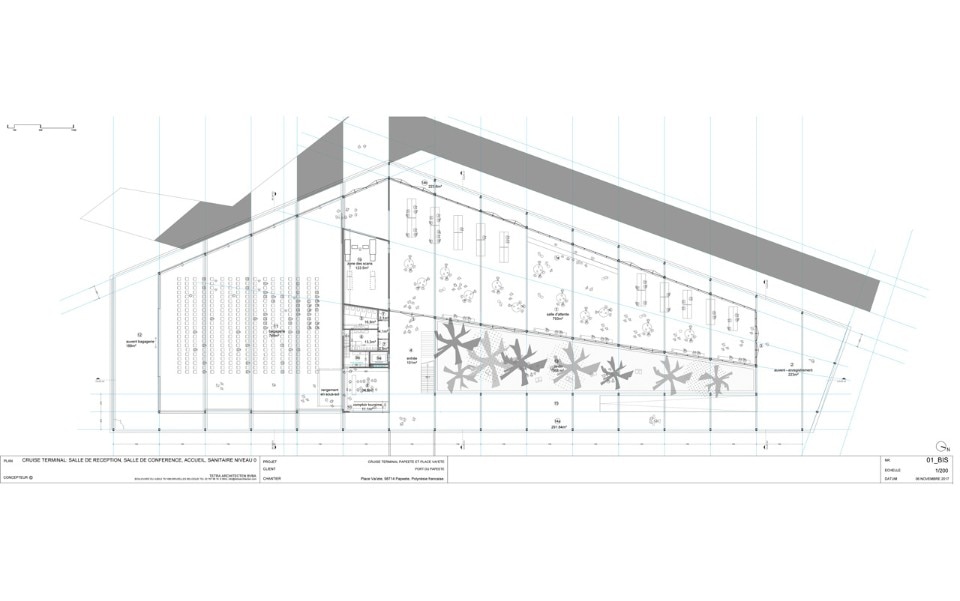

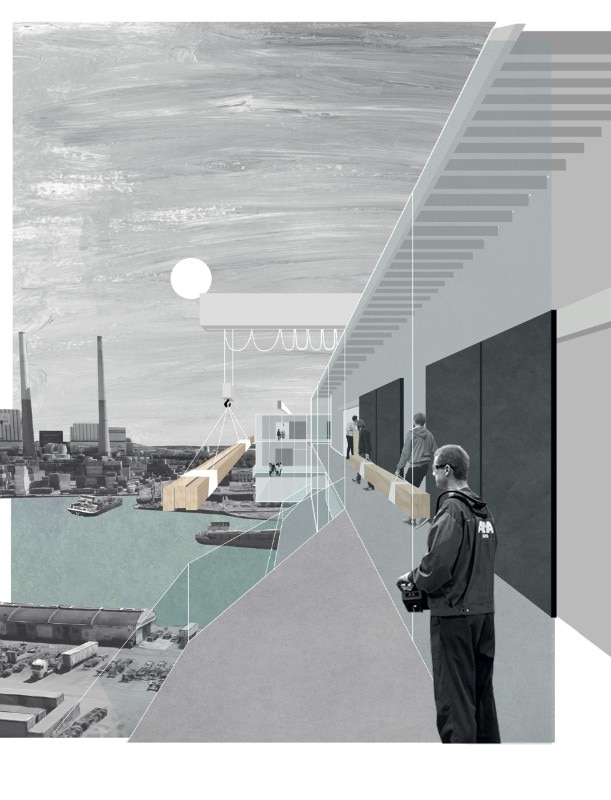

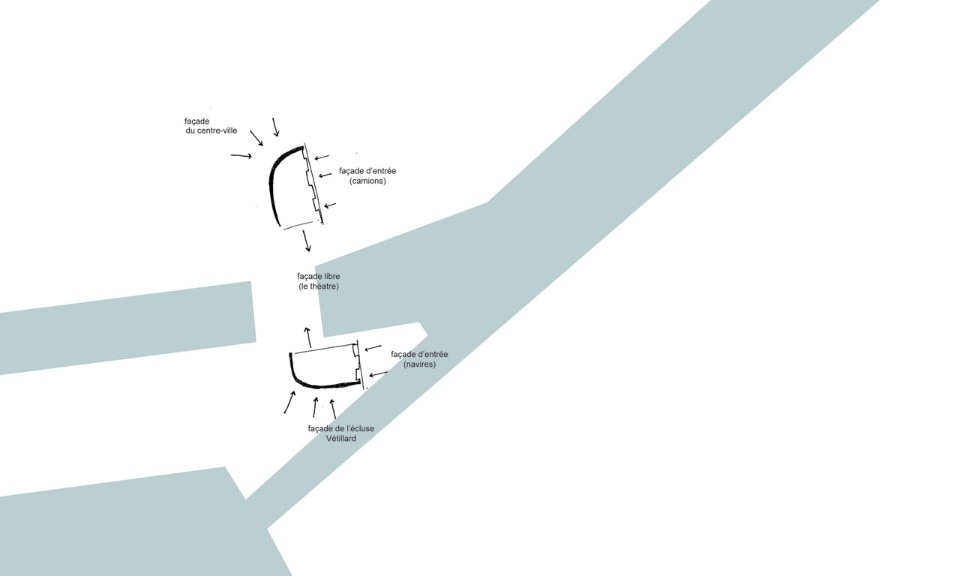

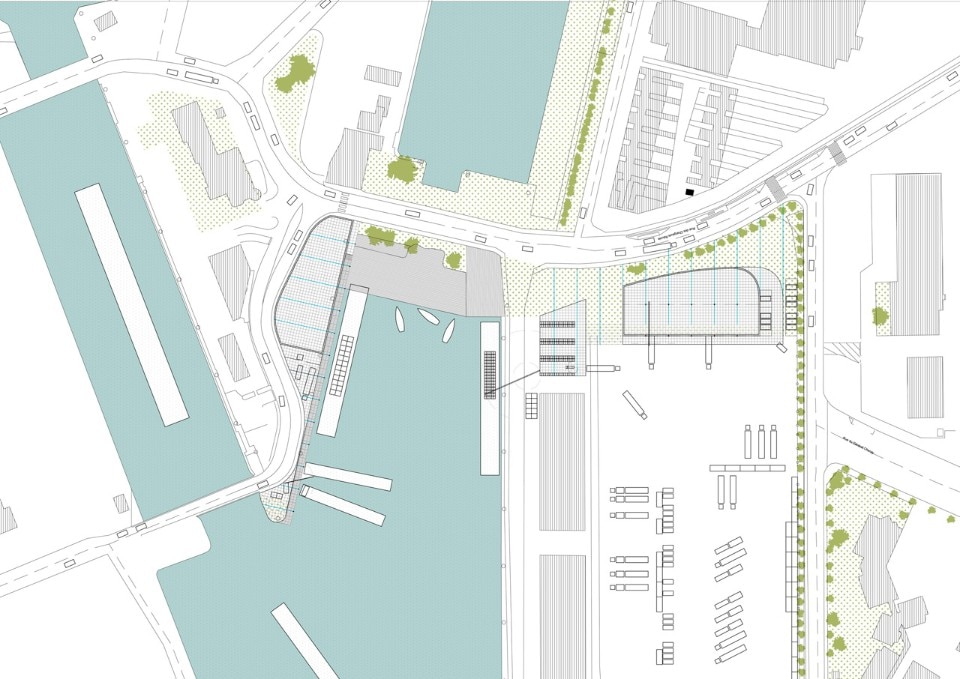

TETRA projects are always part of the urban context. They aim to lend added value to both the city and its infrastructure. The visitor centre for the port of Ghent, the construction-material village for the port of Brussels, the cruise terminal for Papeete (French Polynesia), the hub for small businesses? in the port of Le Havre (France) and the Net Brussels garbage -complex project are all examples of infrastructure-related buildings in the urban environment.

View gallery

View gallery

What does sustainability mean to you? Is it a requisite of all your projects?

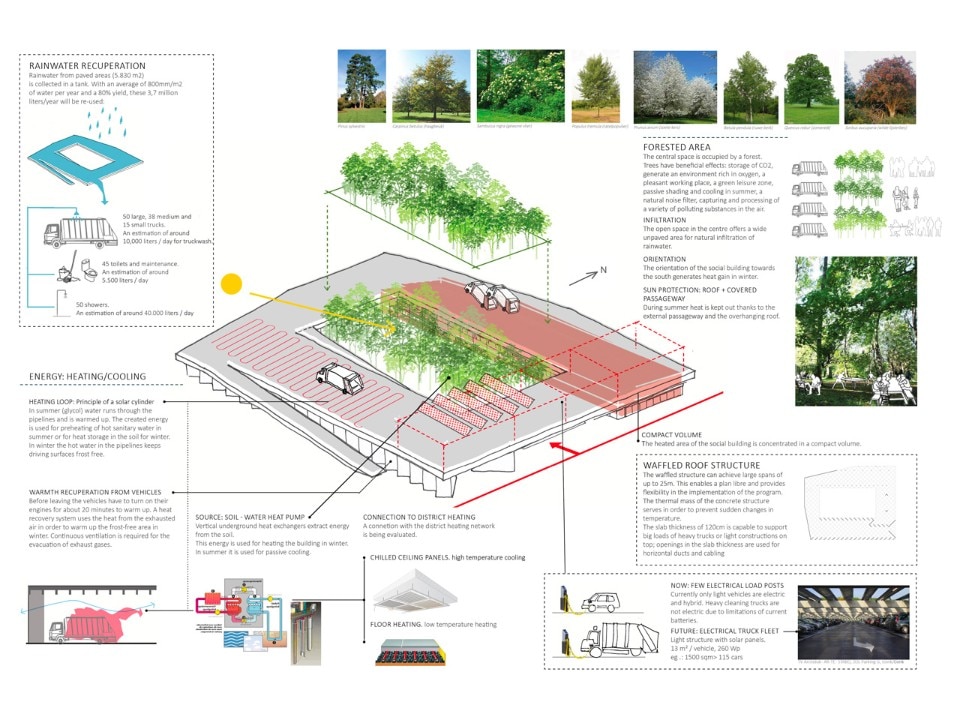

Sustainability is becoming a broad concept with multiple (potential) interpretations. We think sustainability is, first and foremost, about time and place. A building has to be able to stand the test of time without continual and expensive adjustments, for example because of wrong conceptual premises or for maintenance reasons. It must be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances. This does not mean buildings have to be mass produced or repetitive. At TETRA, the creative process of every project starts with analysis of the context and site. The context is often more than just the physical environment. Different aspects need to be explored and tested, depending on the project. These may include historical and cultural background, production or manufacturing processes, programmatic requirements, circulation flows, environmental resources, social aspects, economic feasibility... The result is always site specific, tailor-made for the location. When a building fits into its general context and when it is generous to its environment, it will last longer and will be more easily accepted by the local population.

A few years ago, we produced a scheme consisting in concentric circles. Every circle represents the life-cycle of a building component. The inner circle is for the painting (life-cycle about 5 years), the outer circle is for the context (life-cycle hundreds of years). In between are the finishes (10 years), technical installations (20 years) and structural elements (100+ years). Changes in the outer circle require the most effort, the most energy and are the most expensive. So, if we want to design buildings that can adapt to new needs, we have to design them to include as many potential changes in the inner short-term circles as possible. The outer circles define the intrinsic quality and sustainability of a building. They are not quantifiable, except by lifetime. We see the quantifiable aspects of sustainable architecture such as insulation values, air-tightness, compactness, orientation, ventilation, energy… as some of the technical tools architects must work with as part of their responsibility. They are the baggage in a process in which sustainability is seen holistically.

View gallery

View gallery

View of the living room space with the stove in the center

View of the living room space with the stove in the center

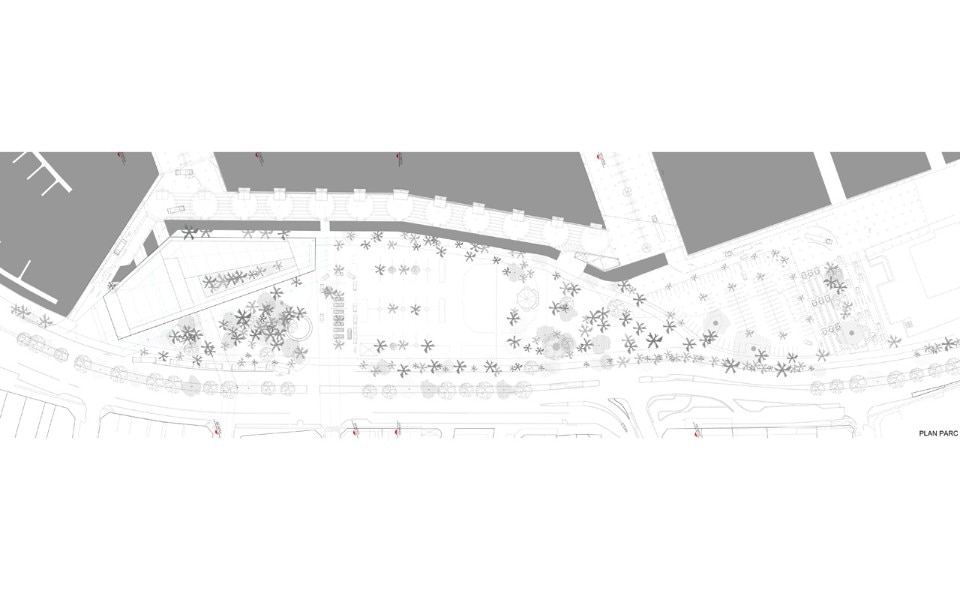

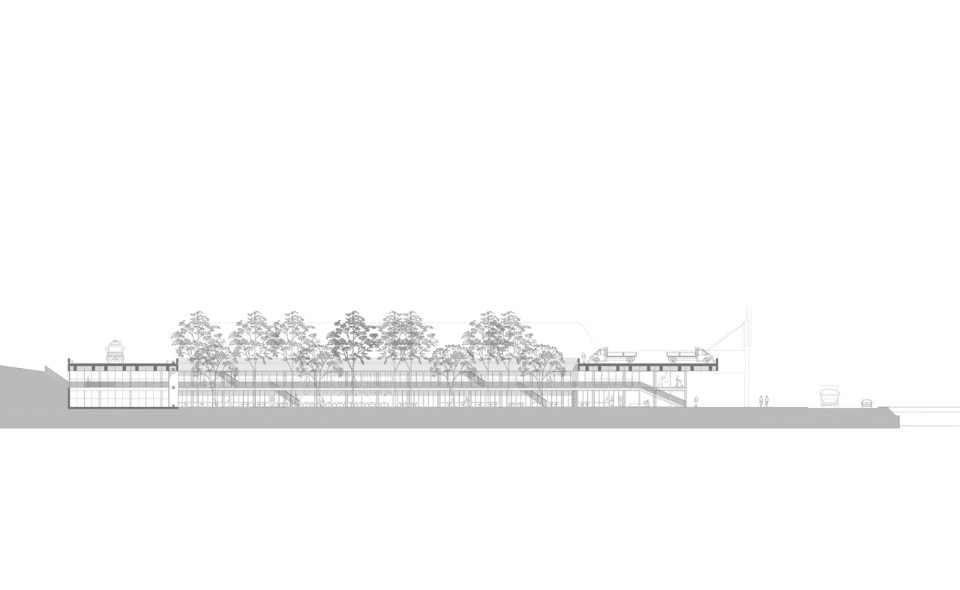

A3-landschap lang-verhardingen

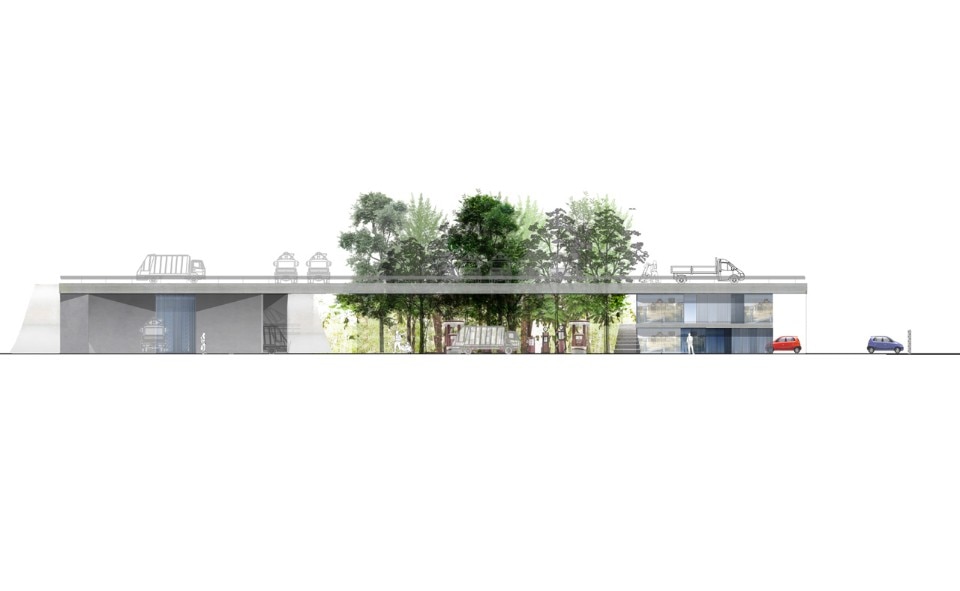

SECTION

SECTION

IMPLANTATION

What made you work on a garbage company along the Canal in Brussels, the project that won you the LafargeHolcim Award. Was it a city administration request?

The project for the Net Brussel garbage company is the result of a competition TETRA won in 2016. For the competition organisation, the client turned to the bouwmeester (chief architect) of Brussels, whose mission is to ensure the quality of architecture and urban space in the Brussels-Capital Region. The logistic nature of the programme, our experience in the canal area (with the construction of the construction-material village) and our background as Brussels architects all prompted us to enter the competition.