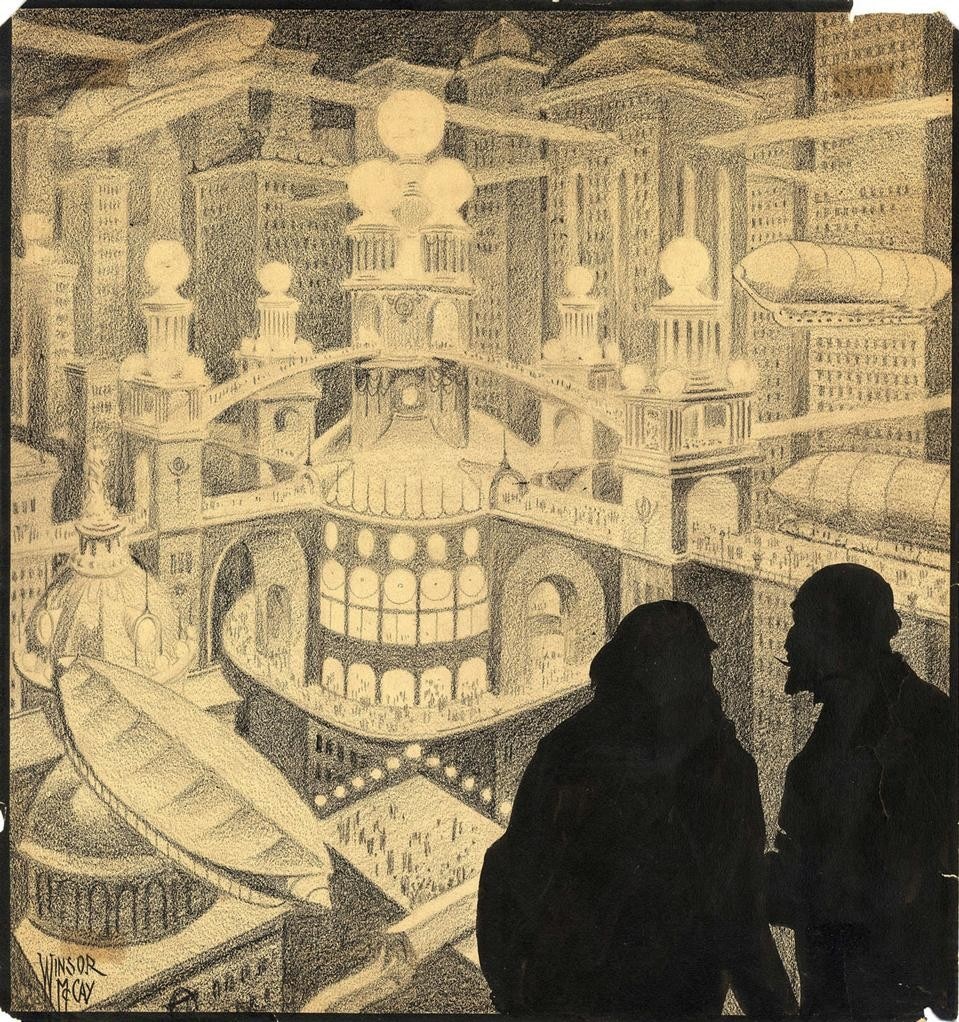

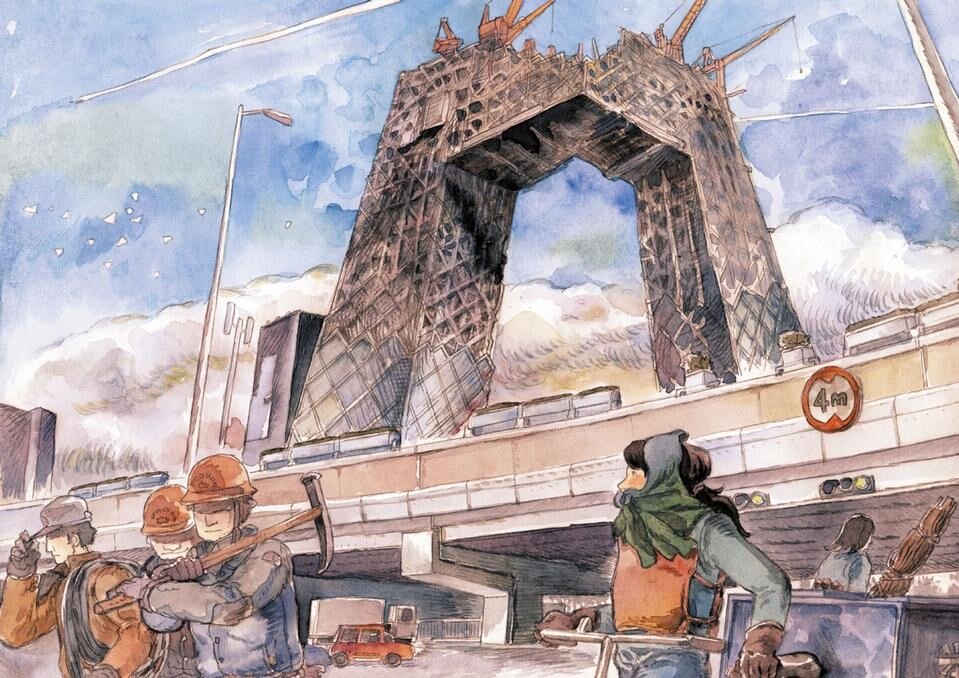

The exhibition "Archi et BD: la ville dessinée" (at the Cité de l'Architecture up to the end of November) tells the story of cities as interpreted by the authors of comics and graphic novels. The real subject of the exhibition is in fact the city, more than architecture. The exhibition has been laid out in a chronological sequence, beginning in the early twentieth century with Winsor McCay, the creator of Little Nemo, a legendary figure who "flies" between buildings in Chicago. At the entrance, a fresco that we commissioned to the French artist François Olislaeger is a free interpretation of a century of architecture and comics brings together comic characters and the most iconic buildings of the twentieth-century, such as the arch by Rem Koolhaas in Shanghai stacked on top of the building by Ricciotti in Aix en Provence, the Caixa Forum in Madrid by Herzog & DeMeuron spiderman throwing himself off Zaha Hadid's ski jump in Innsbruck. It is a reciprocal exchange between two disciplines that have nothing in common, over the course of a century.

What were your objectives in setting up a show of this kind?

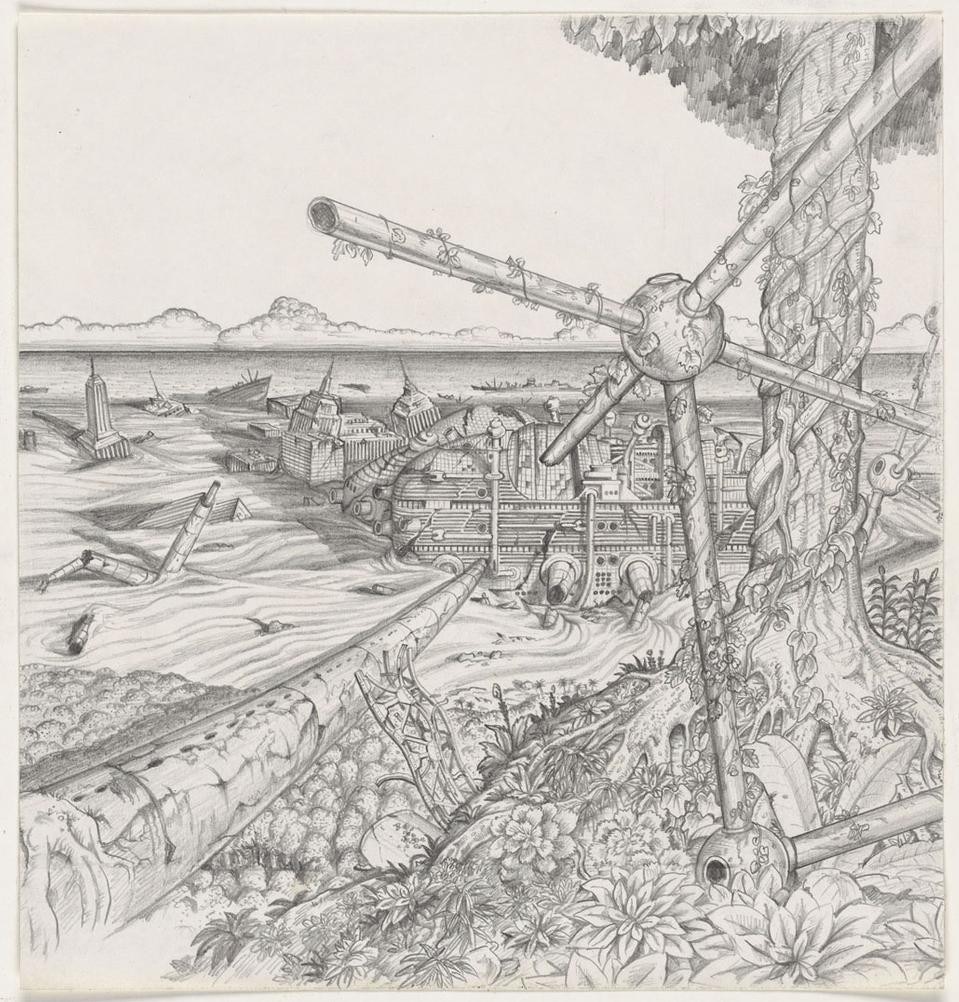

Our goal (and duty) is to attract the general public. Push everyone – not only architects, designers and people of culture – to look at, and, understand architecture in a different way, to look up when they are in the streets, stopping in front of a building. The Cité has about 500,000 visitors each year. In this great site dedicated to architecture they can discover an extraordinary world. If we can help people want to look at architecture, then we have achieved our goal. We believe that the utopian vision, whether it is under the sea or on land like the Walking City, it is important to show that architects have the power to imagine this great city of the future.

Compared to the cartoonists, there are far fewer architects. Why?

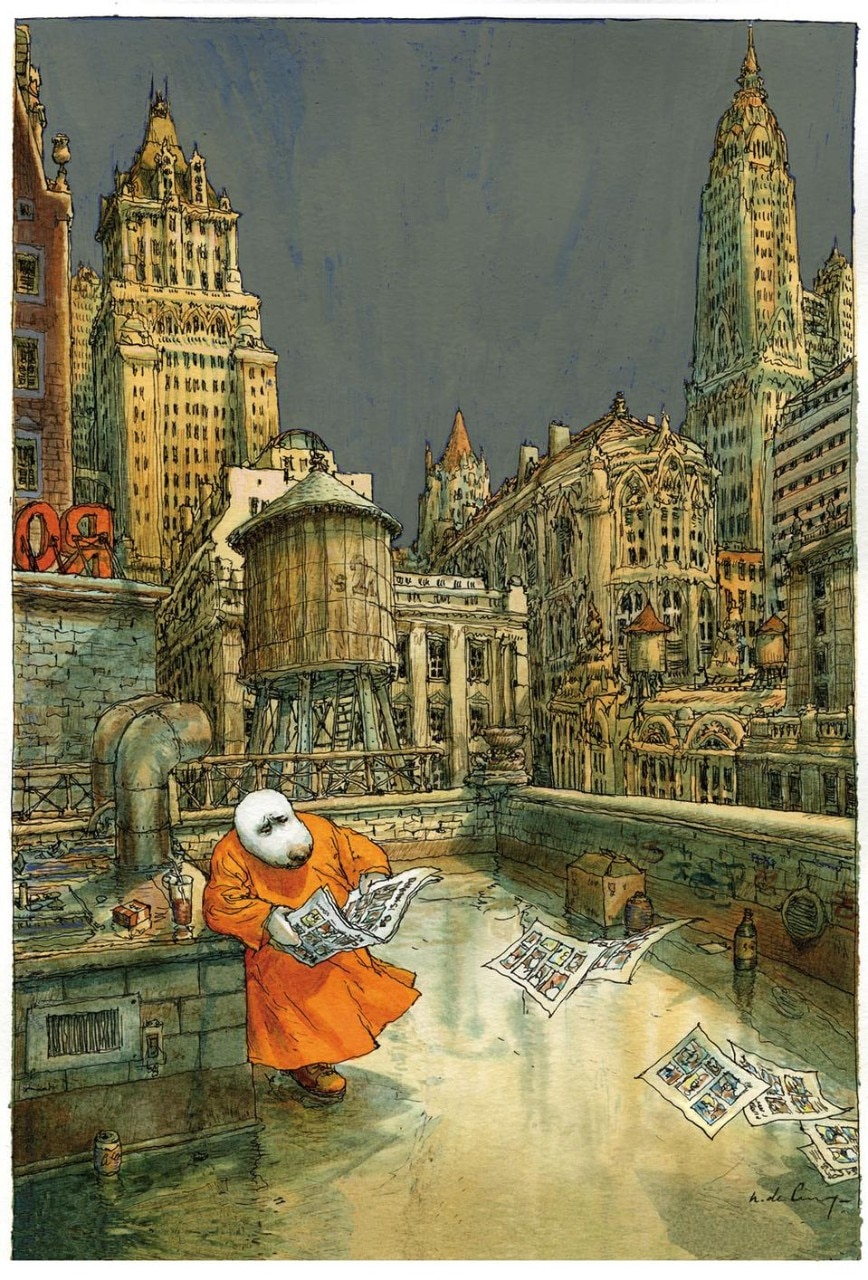

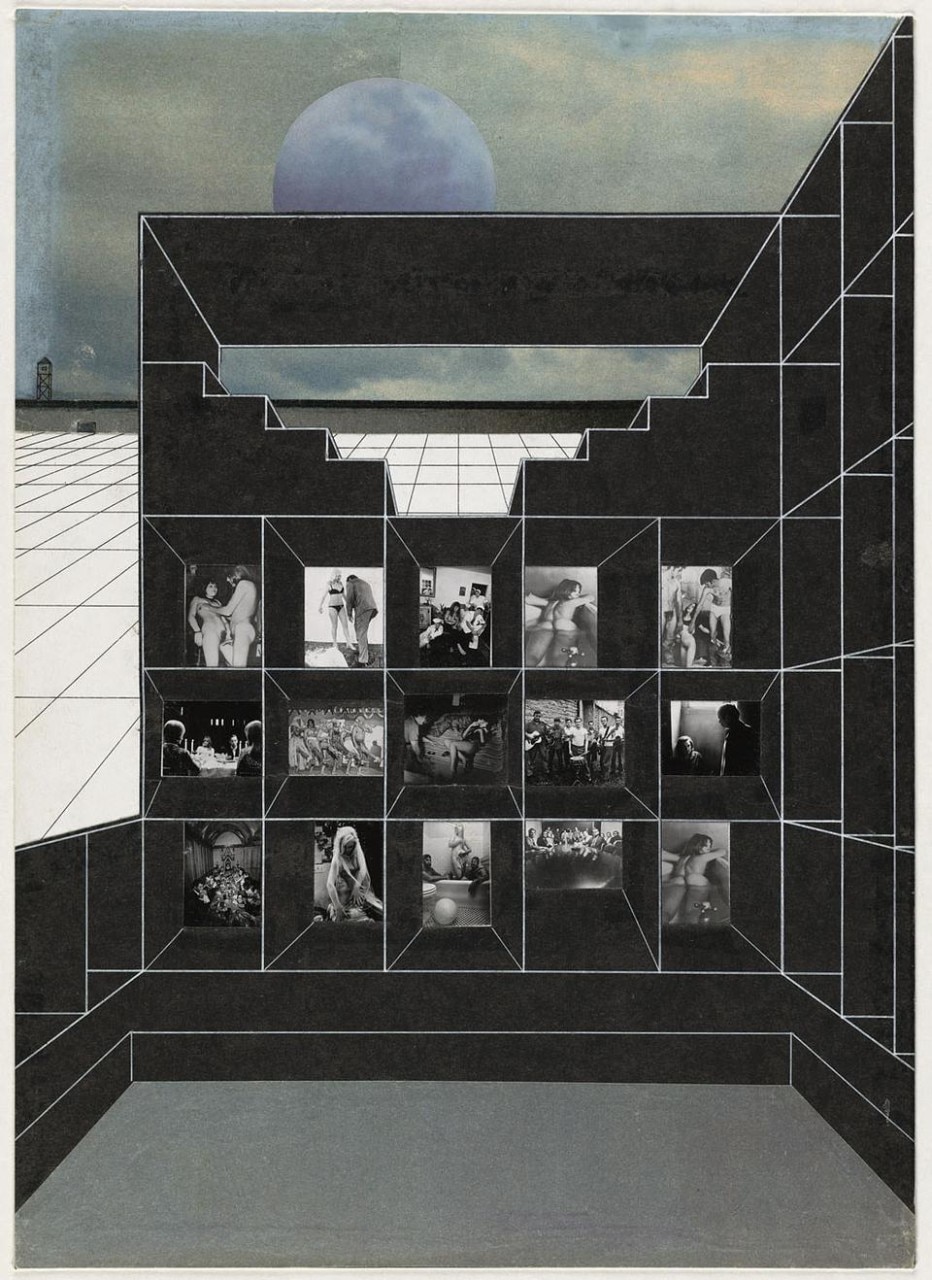

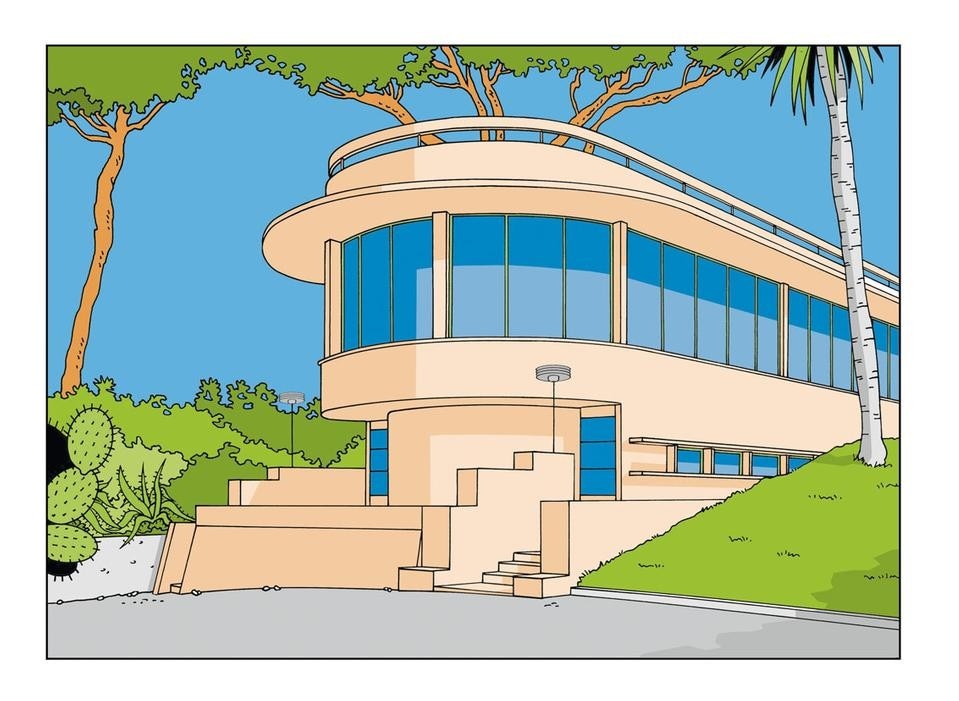

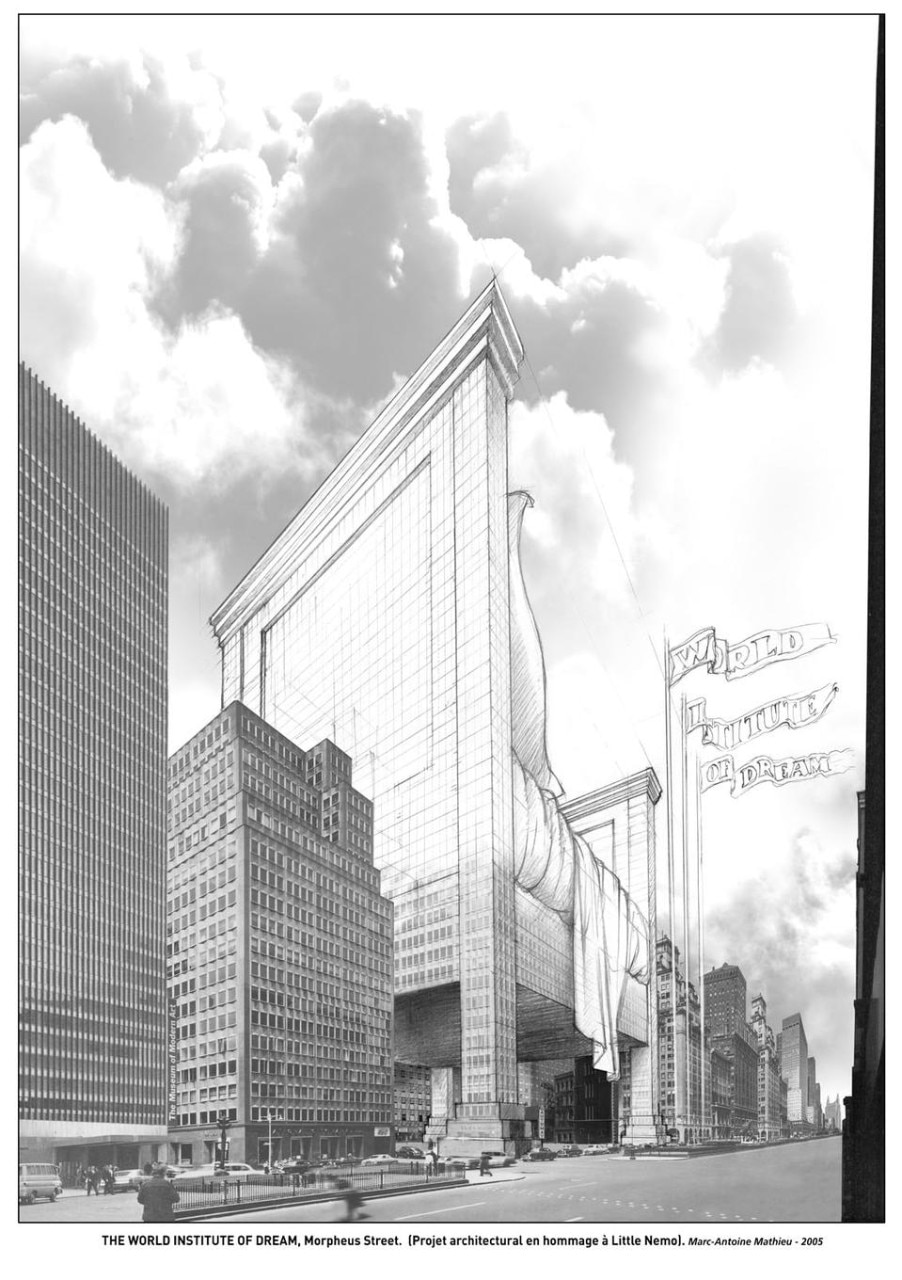

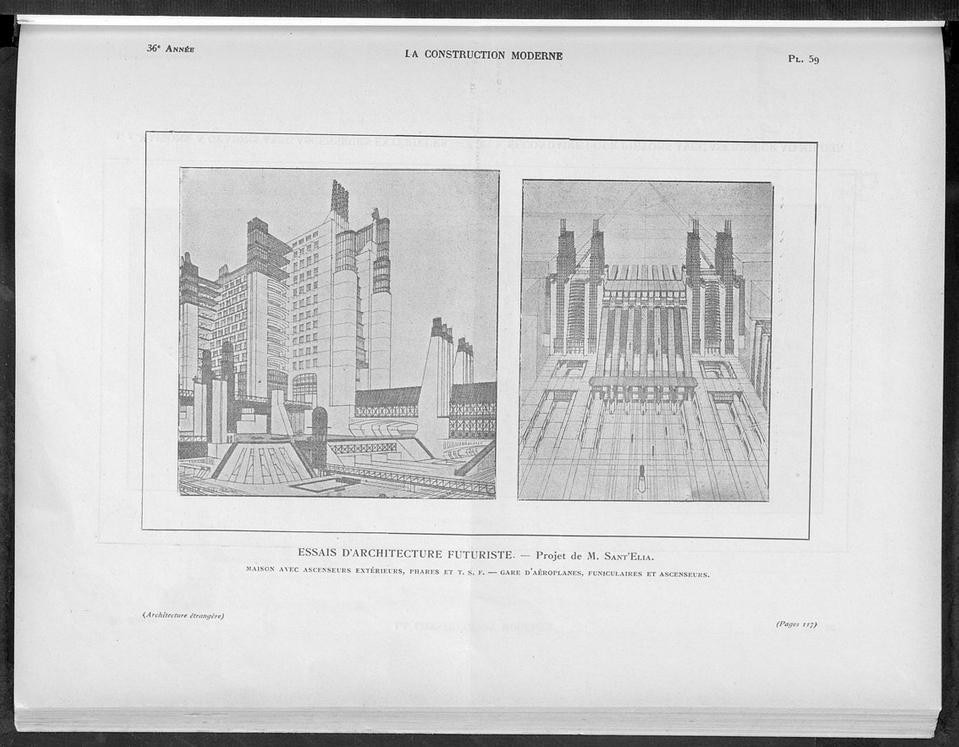

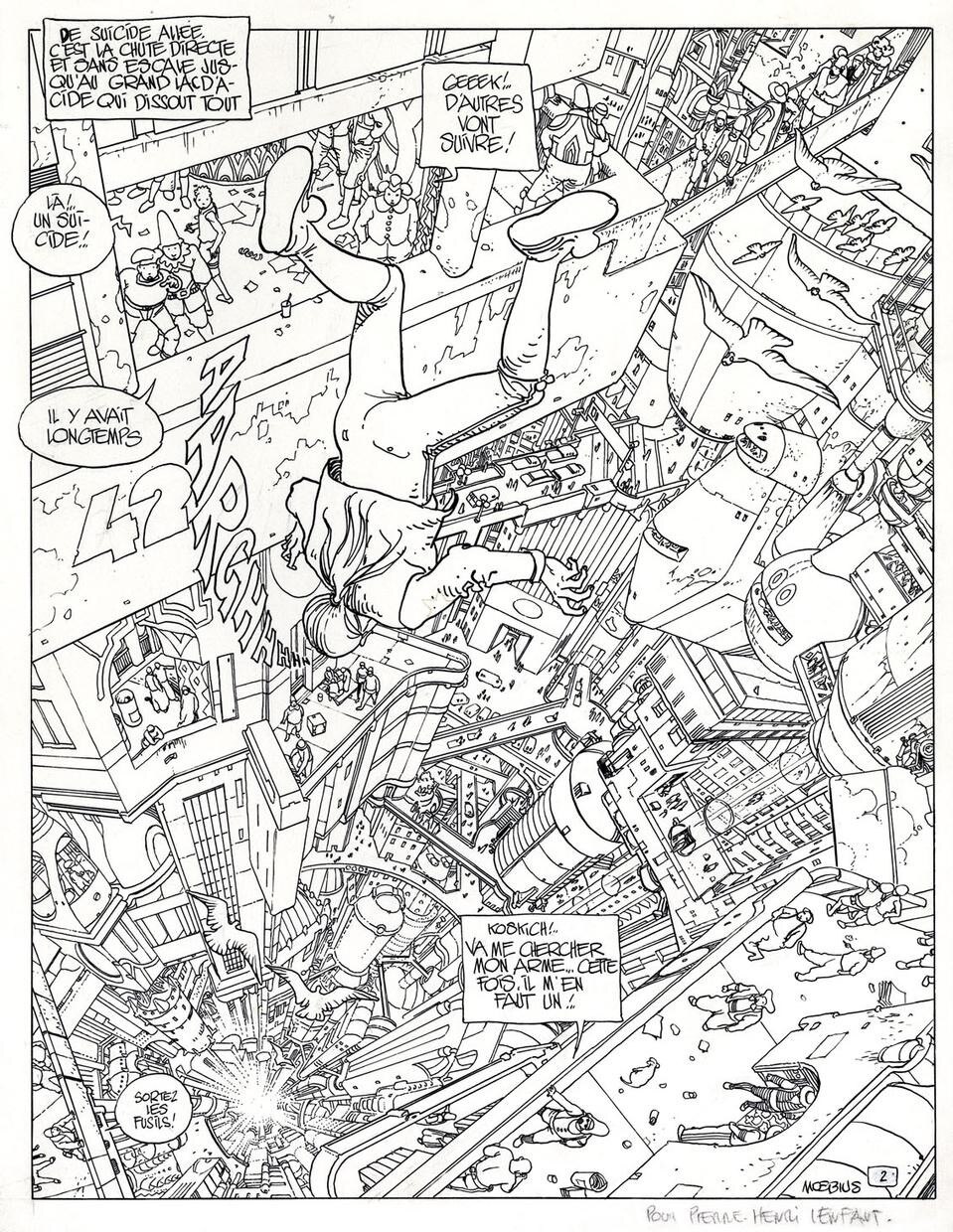

There are 350 pages of comic books and only a hundred architectural drawings by 150 authors. The architects, in fact, are not there to entertain people. Their job is to build and imagine. What we would like to show is the importance of their power in imagining the city and designing it. Their ability to question contemporary society. And it is precisely with these visions that the two disciplines meet. As curator of the architectural section, I enjoyed infiltrating the architecture drawings among the comics. So, after Winsor McCay, there are the urban visions of Antonio Sant 'Elia, and then Friedrichstrasse, the legendary drawing by Mies van der Rohe, which shows the extent to which this building is rooted in the imagination. Marc-Antoine Mathieu, a young French cartoonist, made a tribute to McCay by transforming a skyscraper into bed. In the series by Madelon Vriesendorp for Delirious New York there is a famous scene of adultery between skyscrapers. It shows that even the architects write screenplays based on the city.

Perhaps architects don't know enough about comics to use them?

Indeed, architects more well-versed in literature and cinema. These are their reference points. Think about the number of directors like Wim Wenders, Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard and Ridley Scott that may have influenced architects such as Jean Nouvel, Christian Portzamparc and Bernard Tschumi.

In the sense that, currently, comics take more from contemporary architecture than vice-versa, in the future could comics become to architects what cinema has been in the past?

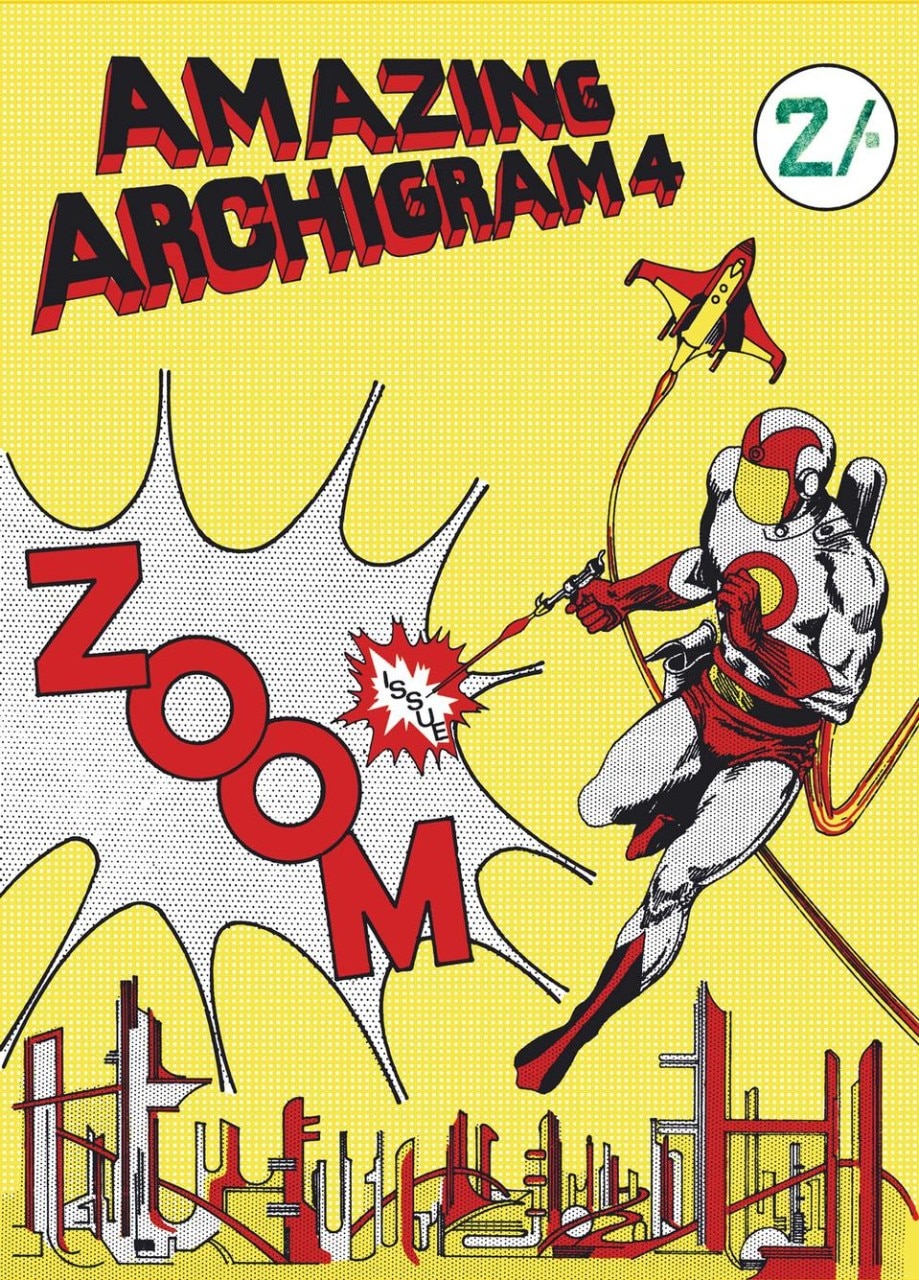

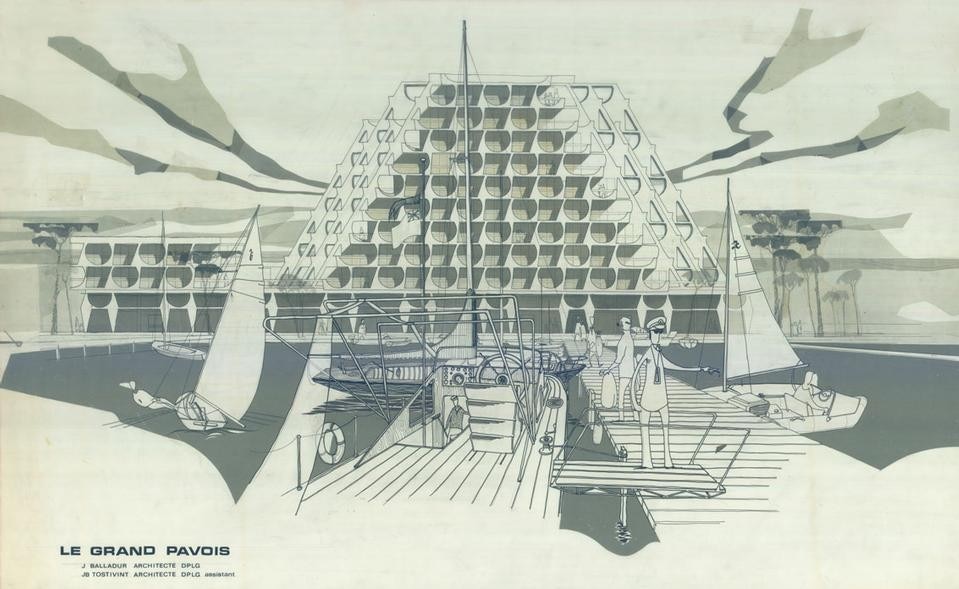

What is certain is that today there is a much stronger transversality than ever before. But it's still the comics authors that feed off of architecture and contemporary cities (even if they live outside the larger cities) rather than the other way around. They take the settings for their stories from architectural magazines. But there are also examples of comics that have influenced architecture. Take Jacques Rougerie, active mainly in the seventies and fascinated by Jacques Cousteau's underwater explorations. He created an portfolio of drawings as if they were comics, about inhabitable underwater structures, showing us how far these possibilities might take us in the future. In terms of utopias, Archigram are the world champions. But we also show a surprising drawing by Ettore Sottsass "Planet as a festival. Disegno per un tetto sotto cui discutere. Prospettiva" from 1973.

Are there architects who have chosen to use comics as a means of presenting their projects? Why?

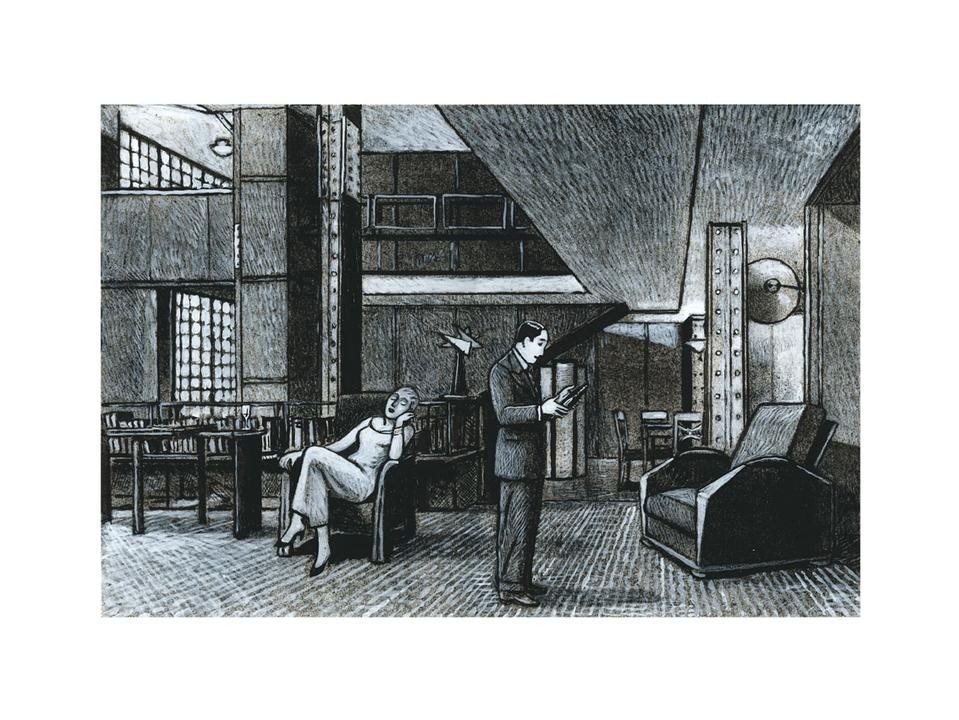

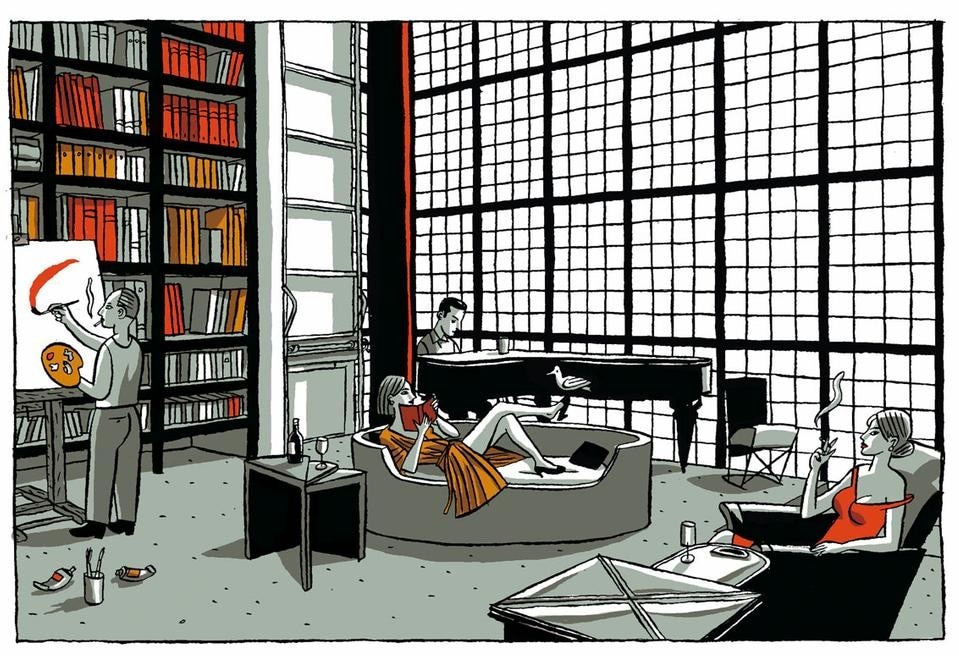

Yes, there are few. For example, Rem Koolhaas in his proposal for Euralille 80 in the 90s, used the language of comics to get his idea of hypermodernism across. To ensure that people (and the government) would understand and be able to identify themselves with a very conceptual project, the networked city, he didn't use floor plans, elevations or perspectives. Instead he adopted the language of comics. With "Yes is more", Bjarke Ingels deconstructs the myth of the superhero comics code and integrates it into his drawings. It's Ingels himself that explains his project, in a conference-like fashion, using a very playful PowerPoint presentation with cartoons that tells a story. It's like a screenplay. Herzog & DeMeuron also made a very interesting comic book. They took Jean Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg from a film by Godard and used them to describe their urban project for Basel, Metrobasel. Their objective is, once again, to be understood by a mass audience. For his exhibition at the Louisiana Museum, Jean Nouvel asked some young cartoonists to intervene in describing his projects. The Japanese group Bow Wow seem to mix drawings with comics, adding characters and illustration even in the technical sections, with dimensions and all.

What are the highlights of the exchange and encounters between architecture and comics?

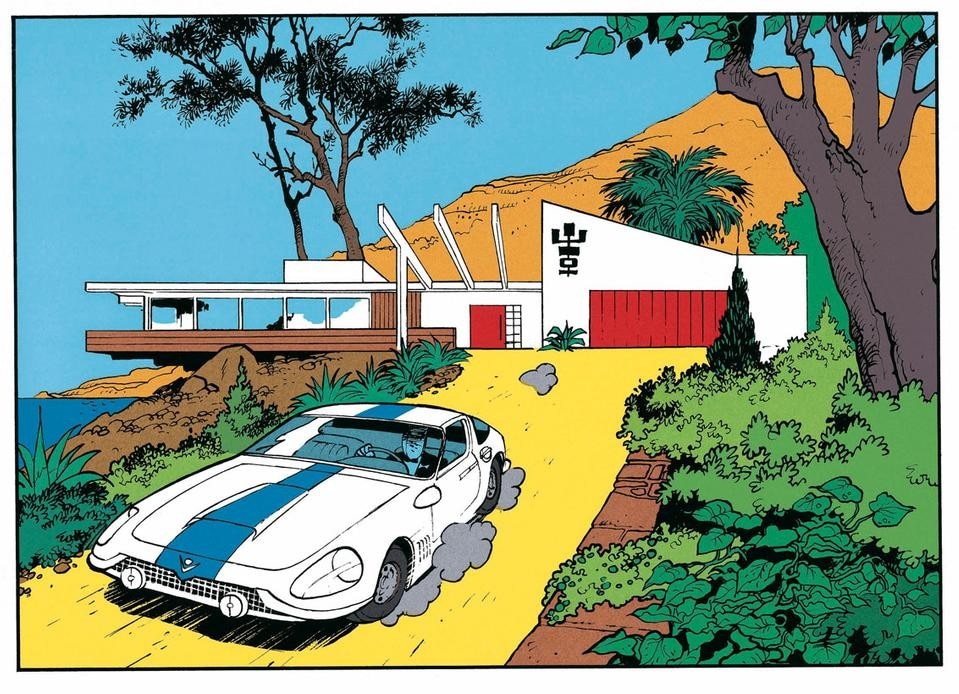

In the history of the two disciplines, Archigram has played an important role because in the sixties they deconstructed the superhero, creating the publication Amazing Archigram, which draws on pop art imagery and makes use of the full range of the language of comics. The second very important moment is in 1958, the year of the Great Exhibition in Brussels. It is at this moment that we realize that comic book authors have discovered modernity. It is the heroic era of architecture – as demonstrated by the Halls of the World and the Atomium – the years of development in Europe. During this period, architecture greatly influences comics.

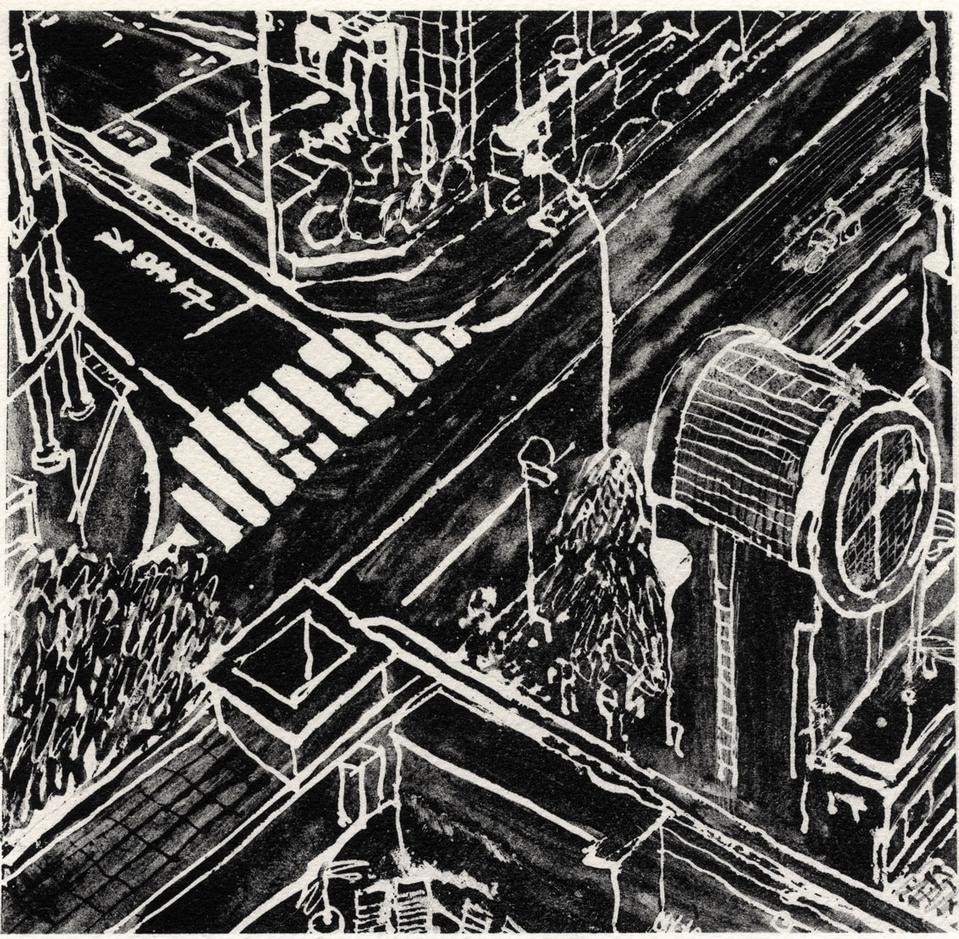

Why are comics concerned with the contemporary city?

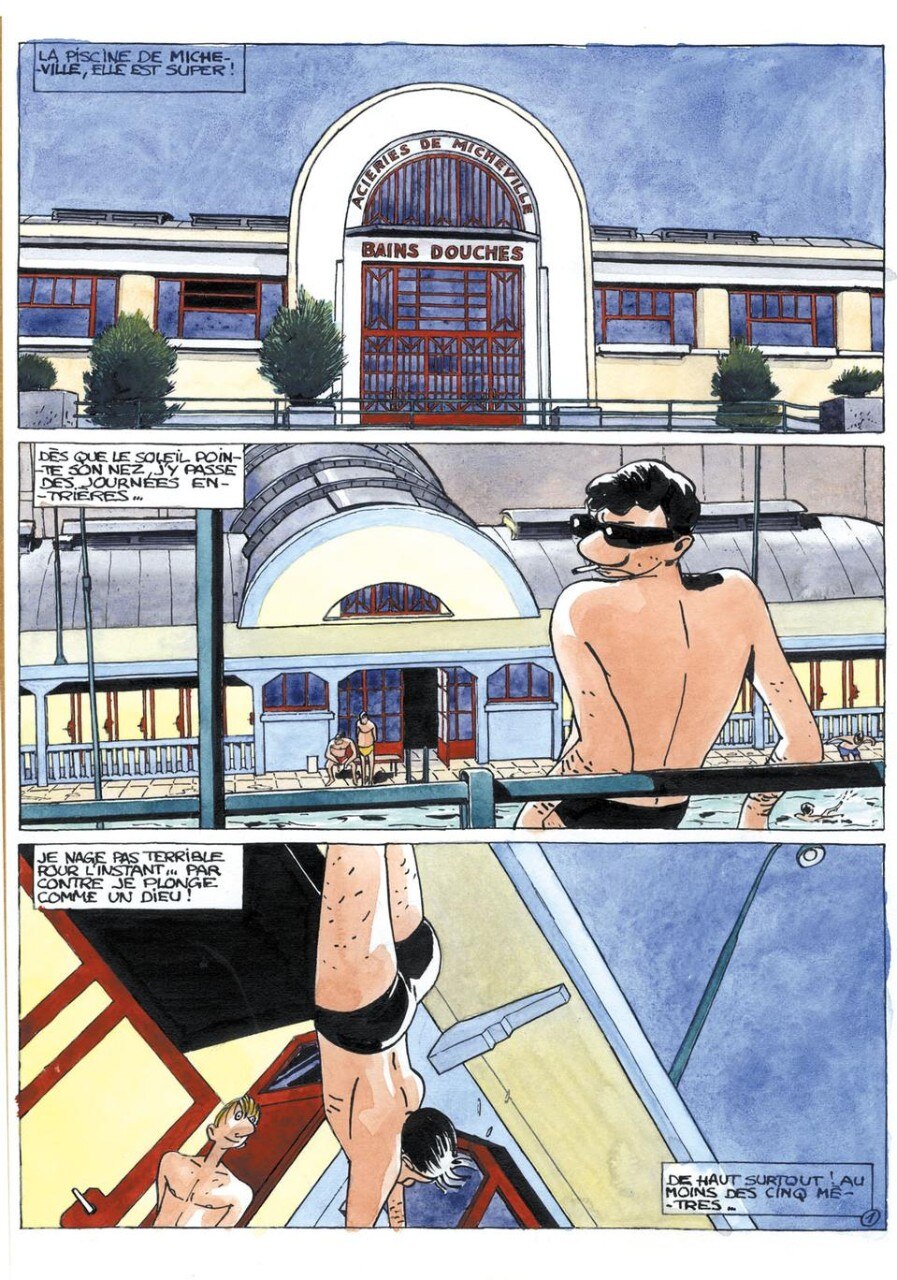

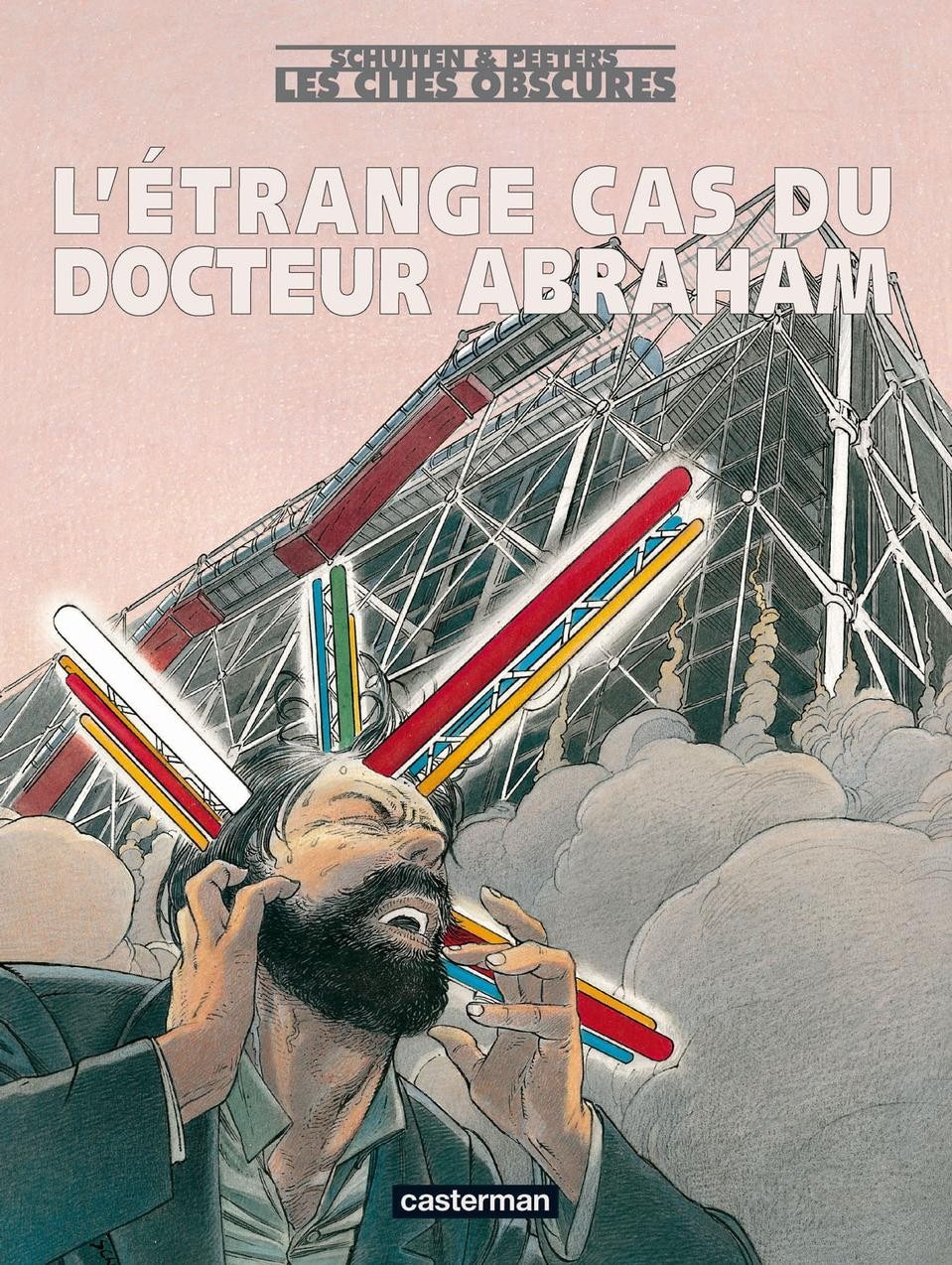

Perhaps because 60% of world's population lives in cities. In any case, it is very rare to find comics set in the countryside. At times, it is the constructed landscape, more than the characters, that creates the backdrop to the comic. François Schuiten, for example, one of the greatest comics authors in Belgium, took great interest in architecture (he was trained is an architect). We could do an entire show on this issue using his work alone. Among the more intellectual authors is Chris Ware. Ware is very interested in architecture (he once had the chance to meet Mies van der Rohe) and made a movie, The Lost Building, about a building by Sullivan that was at risk of being demolished.

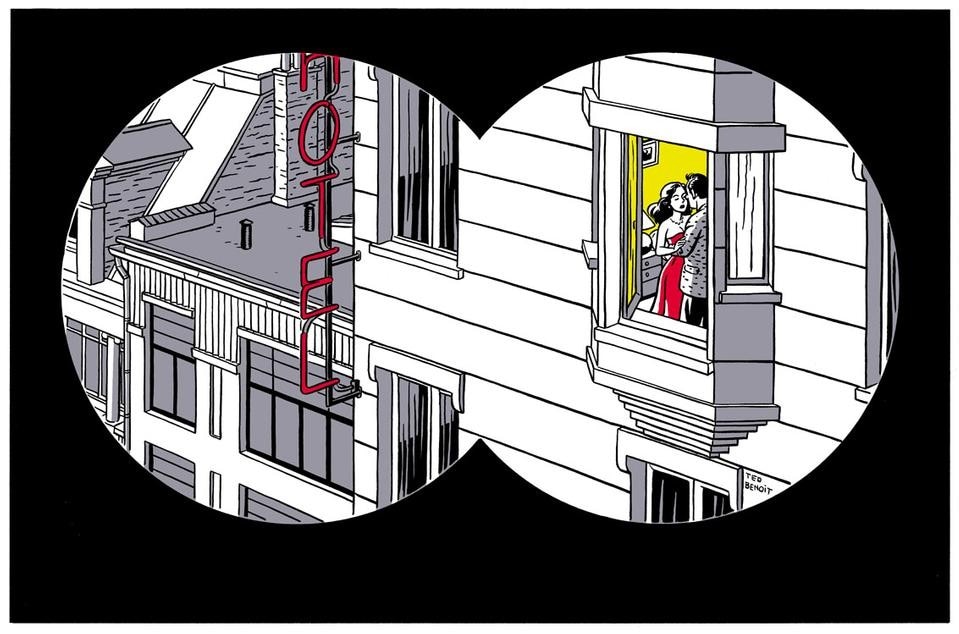

New York, Paris and Tokyo are the three iconic cities for comics: are the cities, so very different from each other, represented in equally different ways?

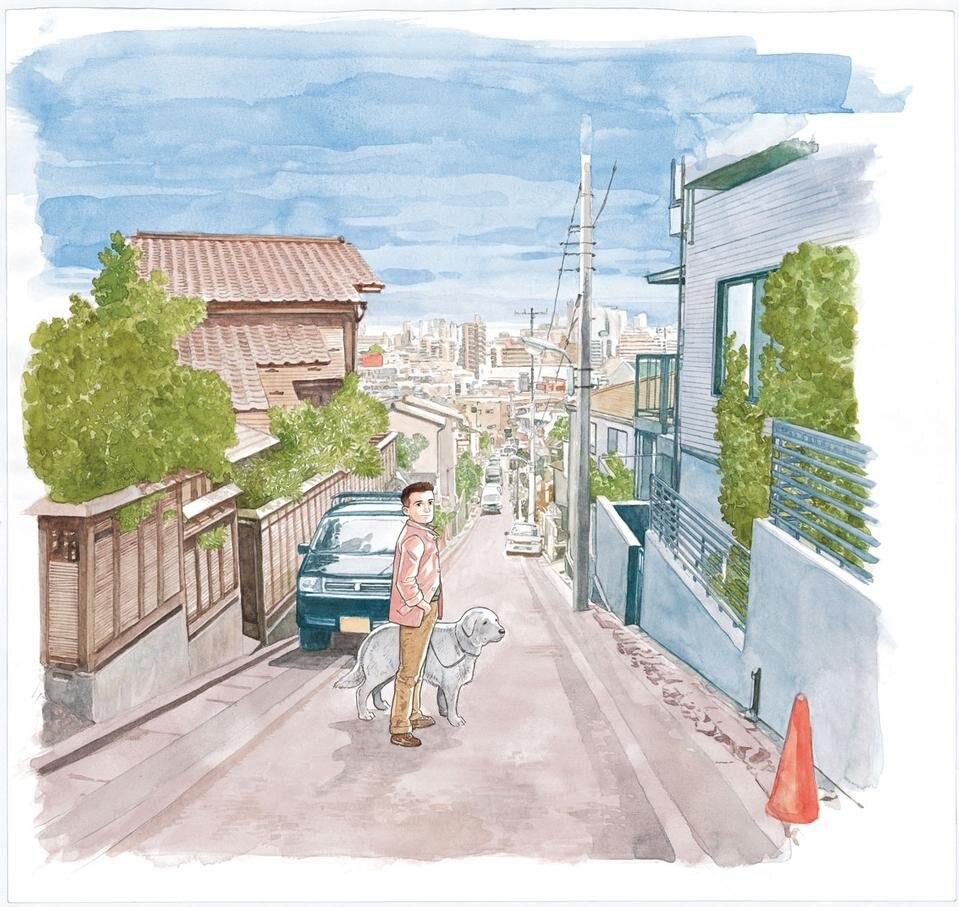

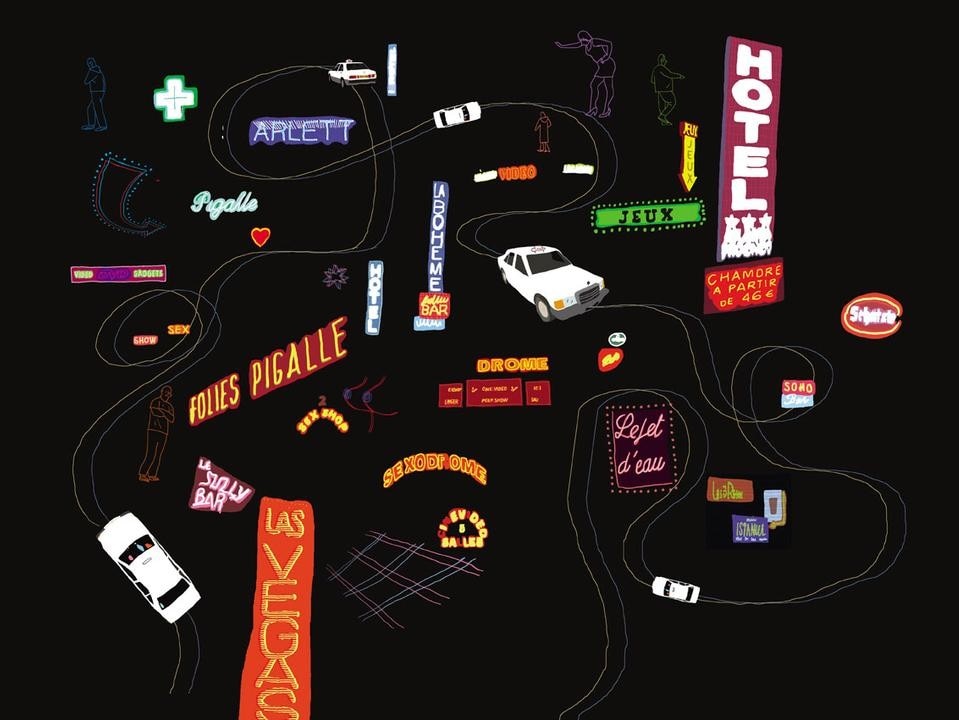

New York, along with Chicago, is the city of comics. Authors use it as a background for their superheroes' adventures of. An extraordinary work by David Mazzucchelli is on the City of Glass by Paul Auster, in which the protagonist walks on the urban fabric of Manhattan. We are not dealing with architecture as a discipline, but, once again, with the city: the way it is inhabited, imagined and lived. Part of the drawings about New York is dedicated to September 11th. And here we see how the cartoonists have appropriated the subject. Next, we placed a drawing by Jakob and McFarlane, a proposal for Ground Zero: giant algae. Paris, however, is identified with a great artist like Jacques Tardi, who wasn't interested in modernity at all. One might wonder if his is a critical attitude towards modern architecture. All of his characters move around in the city of Haussmann. Beside his work comes Louis Bonnier, a nineteenth-century architect who designed a two-lane, divided boulevard, an epoch-making masterwork. Yona Friedman has did an entire series about Paris. It is a utopian vision of Paris in space. Moving on to Tokyo, however, the interesting thing to note here is that comics take no interest in architecture. They don't lookto buildings by, for example, Sejima, Tange or Ando. Instead, they express an urban feeling. A little like in Sofia Coppola's movie Lost in Translation: we're in Tokyo, but we never see the city.

What criteria were used in making the selection? Certainly not everyone can be included, but speaking about New York and the Twin Towers, it's surprising not to find the Pulitzer prize-winner Art Spiegelmann...

Shpigelman is only the one among those we invited who declined to participate. He said he didn't have time. It is a group exhibition that shows the biggest stars of comics side-by-side with as-yet-unknown young authors. And this aspect of discovery is very important to us.

The world of comics is also one that isn't easy to get into if you haven't been accustomed since childhood.

True, plus not all young people today know how to read comics. My culture is linked to Tin Tin, a reporter and great traveler. His amazing adventures around the world formed my imagination. It will be interesting to see the youth of today, raised on television and the Internet.

Which is your favourite drawing?

The work (rather intellectual) by Francesc Ruiz, a Catalan from Barcelona, who took the overall plan of the Barrio Gotico and the Plan Cerdà in Barcelona and drew a story based on these forms, rejecting the orthagonal nature of the drawing in order to fit in with the city plan. It is a work that sums up the show in an extraordinary fashion. The urban fabric is a showcase, it becomes part of another story. What is important is not whether the architects want to use comics, but the communication that is possible between the two arts. It's always been said that comics are the ninth art. Paul Valery said that architecture was the cornerstone of the arts. What interests us is seeing authors from different professions, having different responsibilities, come together on this platform.