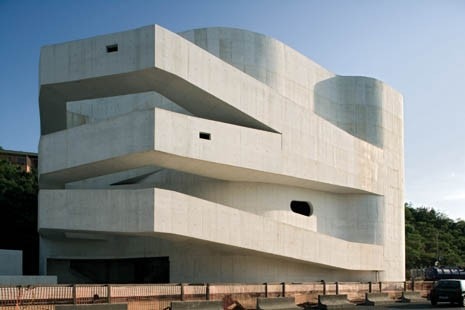

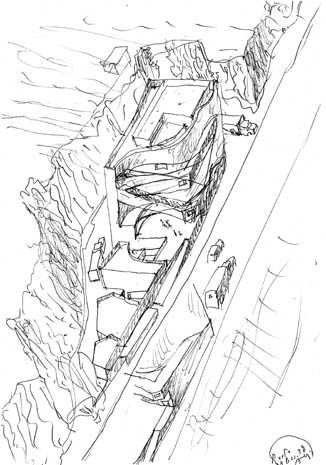

Iberê Camargo was the leading expressionist painter of Brazil. The Museum for the Foundation that carries his name is nearing completion and constitutes Álvaro Siza’s first job in the former Portuguese colony. Though its interiors are still unfinished, the building has already changed the skyline of Porto Alegre, a provincial metropolis of 3 million people halfway between Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires, and the seat of a prestigious Biennial of Latin American Art. Impeccably executed, the mass of white concrete rises in the plain, between the green slope of a promontory and a heavily trafficked avenue along the river Guaíba. As far as one can see, this is Siza at his best, contrary to the opinion of Richard Ingersoll. When the project won the Leone d’Oro at the 2002 Venice Biennale, the American critic dismissed it as an “opaque version of Richard Meier’s High Museum, with a cavernous atrium girded with awkward enclosed walkways” (http://www. techstrategy.com).

Sure, both museums share the same basic scheme. As does Niemeyer’s Casino, now the Pampulha Art Museum. An L-shaped circulation spine adheres to a prism divided in four quarters, three of them containing superimposed galleries, while the internal one becomes a covered atrium. As Siza once remarked, L-shapes (as in his Granell Foundation) and U-shapes (as in his Serralves Museum) are disciplinary tools that lend themselves to myriad appearances. The opacity and massiveness of his Brazilian job are justified by museographic requirements, the western exposition and the noise of the avenue. Yet, echoing Lina Bo Bardi’s tricks in the Recreational Center of Pompeia, the openings that seem minimal from the outside enlarge telescopically inside, here framing the river, the sky, the vegetation on the hill and the downtown peninsula 15 minutes away. Siza has provided a machine for contemplation in more than one sense.

This belvedere is also a landmark. Far from cavernous even now, the atrium curves to face the incoming avenue, girded by a system of double ramps linked to lifts in their extremities. Uninterested in the free plan and facade, Siza does not employ a skeleton structure, but he shares Le Corbusier and Wright’s fascination with ramps. The internal ones are open and follow the atrium’s curved wall. The exterior enclosed walkways free themselves progressively to become handles and generate a striking uncovered atrium. From afar they appear as a Henry Moore helmet before a splendid vase that owes something to Aalto. Their awkwardness is definitely deliberate, as both Lucio Costa and Lina Bo would have counselled: a reminder that perfection is not from this world, surreally replicating the marvellous ingenuity of a child’s drawing.

In the opposite corner of the ground floor, which will accommodate the reception and museum shop, a convex cut generates the covered service platform and cooperates with the aerial ramps to lighten the four-storey volume of the museum. Enlarged upwards, it becomes a happy counterpoint to the slope. Once more Wright’s Guggenheim comes to mind, as much as Niemeyer’s museums in Caracas and Niterói. However, unlike the monotone geometry that distinguishes those examples – an inverted and twisted cone, an inverted pyramid and a cup respectively – the tying of the ramps at their extremities emphasises two moments of verticality as well as a diagonal symmetry, thus vitalising the stratification of the main facades, their figurativeness exaggerated by the plain elevations towards the hill.

Actually, this volume emerges from a platform covering a basement level that houses storage rooms, administration offices, a library, an auditorium and two workshops as well as the garage below the avenue. It does not stand completely alone but is complemented by a lower wing. Triangular in plan to fit the arrow-shaped half of the site, this annex is a spread-out prelude to the museum proper. A light well separates the volume containing the upper sections of the double-height workshops from the cafeteria facing the uncovered atrium. Those fragmented pieces resemble armour plaques over an extended arm, intensifying the anthropomorphic connotations of the ramps while being surprisingly open. When one walks towards the museum flanking the workshops, a window allows a view of the inside and the hill beyond – through the big openings in the opposite wall. Two other picture windows lighten the corner of the cafeteria, one facing the river and the justly celebrated Porto Alegre sunset, the other facing the museum doors. The fragmentation of the wing reinforces the weight of the dominant volume, while the domestic scale moderates its monumentality. From afar or mid distance, the extended composition sports the density of an urban block without losing the characteristics of a block in the park. Ambivalence is a constituent factor of Siza’s Brazilian venture and that seems appropriate, as many would say that ambivalence is a constituent factor of “Brazilianess”.

Do you know how a food disposer works?

60% of American kitchens have one, and food waste disposers are becoming increasingly popular in Italy as well. But what exactly are they, and how do they work?