From the terrace high up on top of the Italia Building, São Paulo looks like the most important megalopolis in the world. Not just because of its size – nobody knows its exact population, but estimates range from 18 to 23 million – but because it is also a kind of museum of 20th-century architectural history: from its downtown, reminiscent of Manhattan – or rather of the old Bowery, full of homeless, drunks and bums – to the interminable freeway (flanked almost uninterruptedly by favelas) down which I was driven from the far-flung Guarulhos Airport aboard one of the most dilapidated taxis I have ever taken in my career as a solitary visitor of cities.

From the 47th floor, even the most glowing descriptions of the Manhattan skyline grow pale before the unending expanse of this conurbation. There is a photo by Sebastiano Salgado that may perhaps give a vague idea of it. But it insists too heavily on the smog that blurs everything into the urban identity poetically described by Caetano Veloso in his song ‘Sampa’ (an acronym for São Paulo) as ‘the reverse of the reverse / of the reverse of the reverse / of the oppressed people in the rows of favelas / of the power of money / that creates and destroys beautiful things / of the horrid smoke that rises and turns out the stars’.

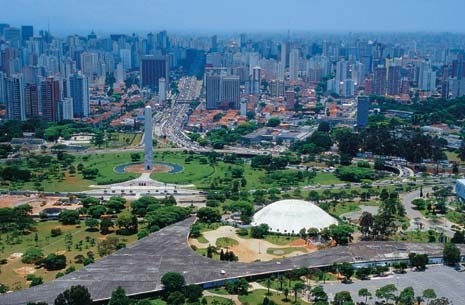

To get one’s breath back and take in healthier air – architecturally speaking as well – one would do better to go out to the Ibirapuera Park, the big botanical garden and small theme park devoted to modern Brazilian architecture. In this sort of democratic E.U.R. – as Brazil had been in the 1950s and hence celebrating true modernity – the most intelligent typological invention is certainly the gigantic marquise: a cantilever, almost a mega-structure in its sheer extent, underneath which to shelter from the blazing sun but also to zoom round on bikes and skateboards or just go for a stroll with one’s girlfriend.

The marquise ideally links the different focal points of Ibirapuera: the architecture designed and built between 1951 and 1954 by a team that comprised Oscar Niemeyer, Zenon Lotufu, Helio Uchôa and Eduardo Kneese de Mello with their associates Gauss Estelita and Carlos Lemos. This includes the Nations, Industry and Agriculture Buildings and, most surprisingly of all, the Arts Building, the one that has for just over a year now been restored and reopened under the curious name of Oca (pronounced Orca, with an r), the name of the native huts used in this part of Brazil. It is now once again a full-fledged gallery after a period of uncertainty during which it had, somewhat mysteriously, risked ending up as an air-force warehouse.

Seen in daylight on the opening day of the show of British art from Tate Modern with which it reopened to the public in August, the building looks more like the classic UFO of 1950s sci-fi iconography than an icon of ethnic paternalism. And like the Copan Tower – whose translucent skin of brise-soleil blades, a few metres away from the Italia Building, affords glimpses of life inside – this structure, too, seems a sublime anticipation of what is today the organic fashion in architecture, the ‘blobmeister’ tendency that has seen certain – not necessarily young – architects harking back to the architecture of those heroic years. Inside the Oca, Niemeyer’s organic fantasy unfolds along a Moebius catwalk beneath the cupola that covers a large empty space.

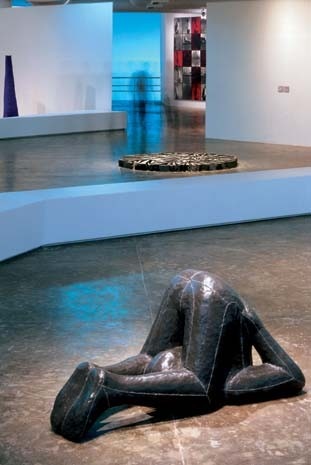

That space is temporarily filled with works by British artists in the Olympus of Tate Modern’s collections, including A Bigger Splash by David Hockney, who these days counts virtually as a pre-Raphaelite compared with Damien Hirst, represented here by the graphic-pharmaceutical series The Last Supper. The show ranges from Hockney, who opens the show with his A Bigger Splash, an icon of the long series of pools portrayed as symbols of the existential void behind Pop society, to the disquieting Antony Gormley, who is capable of expressing the individual’s sense of imprisonment in curled-up human bodies rendered in unlikely materials. The show also presents work by Cornelia Parker, probably one of the best British artists of her generation, who seems ready to blow up a small garden shed and then put its pieces together again, suspended in midair from not-quite-invisible wires. Here Thirty Pieces of Silver is suspended in a sort of stratiform cloud – what remains of composite sets of silver literally flattened under the roller of a stone-crushing machine.

At the private viewing – but now, too, I imagine, that the exhibition is open – visitors seemed to amuse themselves like kids running up and down the walkways to find ever-changing perspective views of this disparate and highly prophetic contemporary British art. In fact, if it weren’t for Niemeyer’s satisfied laugh that one seemed to hear every now and then, in his contentment to see how the effect of his scenographic expedient has worked perfectly, one might well have sunk into the deepest saudade, or into the awareness that, for those who do not cultivate at least some vague hope of a utopia, the Young British Artists are perfectly right to paint and sculpt the ethical rather than the physical decay of Western life.

The day after the opening I managed to speak to Niemeyer, in Rio de Janeiro, at his Copacabana office up in the sky, in the attic of his curious deco mansion flat on the Avenida Atlântica. It was like encountering a saint of modernist hagiography, one who scrutinizes his visitors through tired but intense eyes. In another room, stacked not very tidily, are copies of the catalogue on his pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery, which Niemeyer was recently able to build in London’s Hyde Park.

At 96, Niemeyer apologizes for being able to spare only such a short time for visitors – ‘I have many responsibilities and many people to look after’. In effect, his office is populated with various architects discussing current projects, more geometric icons to be added to the already rich poetry of his masterpieces, which range from the capital Brasília to the Mondadori Building at Segrate, Milan, and the much-debated little museum of Niteroi, a perfect object/sculpture poised on the cliff, a glass and concrete eye watching over the South American coast and a hard place in which to see anything but architecture and the view.

Niemeyer speaks French, a memory of his years in Paris in exile from the generals, and his sentences flow like memories: short sketches of thoughts, only at times slightly irritated, veined with the impatience of a man who, at the age of 96, would at least like to finish what he began.

‘How old are you? 48? When I was 48, I would have been out there on the beach – at your age I was always on the beach. Let’s face it, architecture is not all that important. Life is more important. You see?’ He picks up from his desk a red cap used on a peasants’ protest march. ‘I went on this march to save the earth. It is more important to change the world.

Do you write? Are you a journalist? I too have to explain my projects in writing first. And when my ideas are too fuzzy in my head I go back to the drawing-board to explain them… and then start again. But I use the medium of writing, and then a lot of models. You want to know why? Why I prefer to put photos of models in my books? Because no one understands architecture’.

‘L’architecture c’est un m.… What do you do when you have to write a book? You do your research, take notes and then you sit down and start writing. You read the proofs, get the book printed and that’s that. It’s there and you can’t do anything more about it. But not architecture: it’s never over.… Next to the Oca Pavilion – no, I haven’t seen how the restoration has gone – an auditorium is planned. We designed it in 1954. And it still has to be built’.

Technology meets aesthetics, with Cordivari

With their rhythmically textured external surfaces, the Run and Seven Lines fan coils become natural elements in the landscape of contemporary interiors.