In Jean Nouvel’s hands, architecture has become increasingly dematerialized. From muscular early work like the Institut du Monde Arabe to his housing project in Nîmes, the architect’s interest has shifted ever further away from structure and mechanical detail. His Cartier Foundation is a building with no real facade; a blur of overlapping planes of glass screens the garden from the street. With no visible structure, no frame for the glass panels and no formal composition, it relies not on tactile qualities but on dazzling light and surface effect.

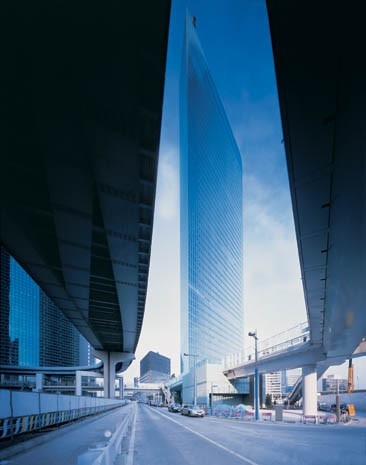

Since then, Nouvel’s architecture has attempted to suppress the heavy physical aspects of building. The newly completed Dentsu tower, Nouvel’s first real high-rise since his Tour sans Fin project in La Défense was abandoned, is a huge structure with nearly 60 floors and 100,000 square metres of office space. Logically, the building should make a massive impact on the city around it, and yet it seems to float ethereally on the Tokyo skyline.

The tower is part of a large new development on former railway land close to Tokyo station. The master plan for the area includes a number of projects by Western architects, including a much lower office tower, originally planned by Richard Rogers but now being completed without his involvement, and a shopping complex. The building was built for the Japanese advertising giant Dentsu, which will occupy the majority of the building; a number of restaurants will have the top floor. Nouvel has given the tower a sweeping crescent shape and a glass skin composed of subtly graded panels finished in a hundred different permutations of grey, which has the effect of making the structure vanish. The building appears entirely weightless, a limpid and very beautiful presence on the skyline. Or at least it does on its convex side, which is glazed with panels made in Europe. Nouvel is not so happy about the other side, fabricated using Asian-made glass that, much to Nouvel’s chagrin, lacks the subtlety and shading of the first facade.

Unlike most buildings in Tokyo, the Dentsu building creates its own streetscape, set back from existing roads and public spaces. Gridless, it seems to bob up against the city, free of any imposed orthogonal geometry. With its ambiguous changing presence – it appears to alter its form in different light and weather conditions – it’s hard to comprehend the tower as a building at all. Inside is the massive steel structure needed to cope with Japan’s vulnerability to earthquakes, but all sense of weight has been peeled away by the glass cladding, which, thanks to its screen-printed dot pattern, gently melts away at the edge of each panel. Inside, with a series of stacked atria characterized by curving, polished surfaces, Nouvel explores another kind of weightlessness. During daylight hours, the stainless steel bands that line the atria mirror both sun and sky, reflected endlessly and unpredictably in the swooping form of Nouvel’s design. On the outside, the quality of the building comes from the ambiguity of its facade: it is impossible to discern where the sky stops and the building begins.

These are effects that are all but impossible to represent before a project is built. Yet this complex series of multiple reflections has much more presence than neutral, analytical drawings could ever show. Nouvel suggests that he is taking architecture to a higher plane by loosening it from the shackles of weight and mass. He conceives the impact that he is looking for in his head, an approach remarkably close to cinema. Like a director working with a skilled cameraman, Nouvel plots his shots well in advance, working out just how to lead us through preplanned visual moments.

The project has a constantly changing effect on the Tokyo skyline. Its form is not immediately made explicit, and its ambiguity is increased by the shading of the individual panels. The tower reveals itself only gradually, and even a complete tour of the perimeter does not make its shape fully clear. From some viewpoints it appears flat, while from others it seems sharply curved. Like a cloud, it appears to have been liberated from physical form.

Wood: a key resource for south tyrol

In this northern Italian region, wood is a vital resource that brings together tradition, the economy and environmental protection. The short and sustainable supply chain is worth €1.3 billion and involves thousands of local companies.