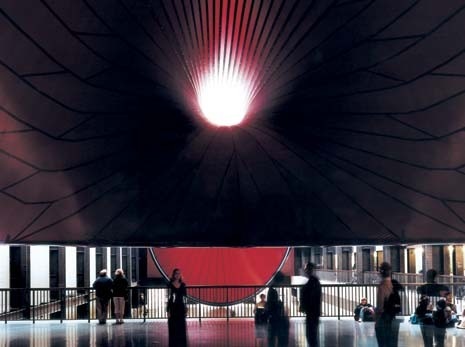

Something happens to art when it gets really big. It starts to spread out of its box and colonize other areas of human endeavour, like architecture, sport and the entertainment industry. This can be confusing, since we like to think that art is special, that it occupies a unique place in our hearts and minds. But when it involves an engineering firm, official clearance from Health and Safety and a team of hard hats, then one begins to question this distinction. The installation of Anish Kapoor’s leviathan new work in the turbine hall of Tate Modern, London is a case in point. Entitled Marsyas, the project is the third in a series commissioned by Unilever – the first was by Louise Bourgeois and the second by Juan Muñoz. This new piece occupies the entire length of the turbine hall, which itself measures 155 metres long, 23 metres wide and 35 metres high. The work is the largest the artist has ever realized, consisting of a vast ‘sock’ of blood-red PVC membrane stretched tight by three giant steel rings, one at each end and the third suspended horizontally in the centre, two and a half metres above the pedestrian bridge that bisects the space.

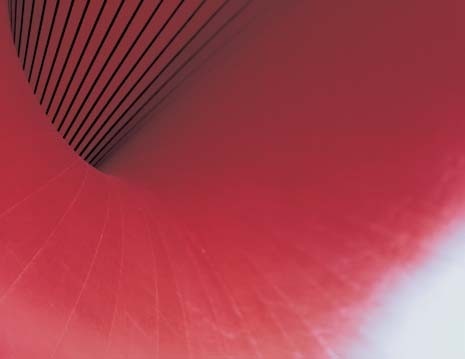

At the hall’s west entrance, the giant steel ring is oval in shape and tilts toward the end wall by a few degrees; at the east end, the ring is circular and cocked to one side so that it misses the last of Herzog & de Meuron’s light boxes. At the centre, the horizontal ring is suspended over the bridge thanks to the tautness of the internal supporting system of the PVC membrane, which, rising many feet above, is slung from one end of the installation to the other. The effect is spectacular and uncompromising: a pair of giant red mouths sucking inward and linked by a moment of carefully calibrated release at the diminishing centre of the tube, where the middle ring, framing a circular cut in the membrane, allows visitors to gaze up and be immersed in a cloud of red space. ‘The sheer thrill of this scale, of this monochrome, is what fascinates me’, says Kapoor as we gingerly tread our way across the guide ropes and folded piles of PVC membrane still awaiting the gradual tightening process necessary to complete the installation. He wears a vivid yellow safety jacket that bears – unknown to him – the legend ‘Art Technician’ on the back. ‘The bridge in the middle is problematic’, he says. ‘It breaks up the space massively and makes it into two main areas. I can either fight with the shelf or use it to link all the space together to make a passage of experience. It thus becomes three discrete events linked by a hose’.

There are precedents for this mega-piece in Kapoor’s career: the two most identifiable are his 1999 installation Taratantara for Baltic, the new art gallery in Gateshead in the north of England, and his sculpture The Edge of the World, which featured in his 1996 solo exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London.

In the former, Kapoor worked with an unfinished building that was, at the time, a giant box without a lid. Also made of PVC membrane, although of a lighter, pinker hue and half the size of the Tate piece, the installation, with its suggestive sense of a giant inhaled and exhaled breath, seemed to express the nervous potential of the transformation the former flour mill was undergoing. As such, it seemed interestingly opportunistic in its intent. In the latter piece, Kapoor explored the experience of visitors who, finding themselves walking under a lowering circular object that resembled a magnified red blood cell, were made to feel conscious of the lipped edge of the sculpture and thus, perhaps, of their own proximity to the outer reaches of known experience. ‘I had a certain resistance to using a membrane again’, Kapoor says of the Tate installation. ‘We explored other possibilities – an object that sat on the bridge, something resembling a big kidney bean shape. But I felt this wasn’t enough. It was too recognizably a known Kapoor shape’. Instead, his ambitions were grander: ‘I wanted to turn the building inside out, to shift its perspective from the vertical to the horizontal axis’. Anyone who knows the silhouette of Tate Modern knows that this strategy in effect constitutes a metaphorical ‘unbuilding’ of its architecture. The artist expands his argument: ‘Modernism’s proposition is toward phallic form. But we’re living in a different age. Carl Andre’s work, for example, proposes that we reaffirm the flat, the earth, and make it, once again, of cultural interest’.

The reference to this arch-minimalist confirms something of the parentage of Kapoor’s work. ‘Andre’s work suggests that the Dantean world, a descent into the underworld, is more interesting’. The installation cannot be seen all in one go. You have to walk around and underneath it to grasp its size. It is, however, defined by the space and structure of the turbine hall. And this is one reason why I think this piece is not architecture per se: it exists in relation to the building but is not part of it. While it has no human scale, it is impossible to describe this installation without having recourse to the corporeal language of the body: its vast tubular membrane is ‘vascular’ when looked into from the end or inside the middle ring and ‘muscular’ when seen from the outside. ‘The word “membrane” is also charged.

It suggests something liquid, impermanent’, adds Kapoor. The title of the work is also highly significant in this respect: Marsyas, as any classics student should know, was flayed alive by Apollo for daring to challenge the god’s supremacy in music-making, and once you know this, the red membrane’s stretch is potentially repulsive. Investigate the tale further and you learn that Marsyas was half human, half satyr, and was punished because he tried to mock the skills of Apollo, the god of the arts. I wonder if this piece is also about punishment as well as the epic tragedy that comes from daring to challenge orthodoxies. Or that we had best remember the part of us that remains satirical (satyr-like), untransmuted into ordered perfection. ‘Marsyas was an early martyr, I think, a prototype for the crucifixion. And goodness knows there are conflicting views about martyrs today’, Kapoor says. He dodges the question whether he sees himself as Marsyas, but it’s worth reminding ourselves of Kapoor’s recent forays into architectural collaboration. In both instances – submissions to the Diana Memorial project in Hyde Park and a design for the Jubilee Gardens site on London’s South Bank – the architects in question were Future Systems, a practice whose signature ‘blob’ architecture could be said to echo Kapoor’s own distinctive artistic style. ‘Making a sculpture is not about making a more or less interesting form’, he says, implicitly drawing a comparison with architecture. ‘It’s about searching for a content’.

His experience on the Diana project was not altogether pleasant, and it underlines the frustrations that artists, unused perhaps to the mundane competition selection processes that architects and designers invariably have to go through, can feel in such situations. ‘The selection process was amateurish. Buckingham Palace’s need to be involved in the process should have been declared up front rather than lurking in the background’, he says. As for his role in shaping a proposal for what in effect is to be a shrine to Diana, he points out that ‘memorializing is extremely difficult, especially if you forego a figurative language. The presumption, when it steps away from an overtly figurative language, presents an immediate problem that has to be solved. I’m not against sentiment, only sentimentality. If one makes a compelling work, its stature and its power are evident by the nature of what it is’. Unfortunately, the closed form with a gushing fountain of red water that Kapoor wanted as part of the six-metre-high and twenty-metre-wide project for the Serpentine Lake was just too symbolically ‘bloody’ for some: ‘it was a banal reaction’, he fumes. The advantage of gigantic scale, on the other hand, is that it assimilates the language of abstraction and is less easily assessed on figurative terms alone. As with architecture, Marsyas has required collaboration, too – in the urbane figure of Cecil Balmond, a principal of the engineering firm Arup. This relationship is intriguing: it’s unusual for an artist to have to rely on someone else to give his ideas structure and realizable form. ‘Instinctively we both have a common understanding of form. We also have a good chemistry at a personal level’, says Kapoor. For him, the key thing was to adapt ‘the reality of engineering, which is usually much too present for art. I didn’t want too much evidence of the work being put together.

The question was how to turn the language of the engineer into the language of artistic metaphor. We had to find a way of making engineering invisible, of building it into the structure’. Balmond’s team worked hard to produce the right network of seams that could give the PVC membrane the required strength and structure, developing the piece’s eventual shape in tandem with Kapoor. ‘We went through several stages’, recalls Balmond. ‘At one point we suggested a halo of metal supports around the membrane, but this was impossible in the timeframe we had to work with. I made sure that my diagrams for Anish were coloured in blue and yellow – any colour but red, since I knew how special it was for him’. For all their synergy, subtle differences in language reveal slight differences in their mutual perspective. While Kapoor talks of his work in terms of ‘form becoming space’ and the engineer’s task as that of ‘finessing the form’, Balmond himself stresses that ‘the structure is all that is visible. It is the form. But my art’ – notice the word – ‘is not visible.

I wanted to extend his language and to move it into new territory. I have taken a spatial hypothesis, challenged it and pushed it forward’. Collaboration is all about emphasis. ‘My work is about augmentation and diminution. It’s not editing, it’s more formative’, says Balmond. The interesting thing about Kapoor and Balmond is that, as artist and engineer, they are similarly concerned with first principles. Balmond neatly formulates that ‘archetypes of structure interest me, while archetypes of space interest Anish. But we both delight in the ambiguous’. Asked about the key difference in the way that artists and architects work, Balmond emphasizes that ‘this is really about the difference between metaphor and structure. Architects deal less with metaphor, while the artist is faced with the creative prospect. He’s interested in a self-communicative language, while architecture, on the other hand, is about team production. Much of it is out of your control. The metaphor is harder to carry through due to the dilution it experiences during the production process’. Unsurprisingly, Balmond adds that ‘many architects want to be artists’.

Asked if he has ever wanted to become an architect, he pauses carefully before stating that it is the mathematics of architecture that interests him most. ‘That is my architecture’, he says with a smile. Searching for a strictly architectural equivalent for the kind of collaborative relationship he has enjoyed with Kapoor, Balmond mentions the Kunsthal in Rotterdam, an OMA project, in which he says the engineered and architectural intents of the building are similarly fused and indistinguishable. Indeed, Rem Koolhaas’s preface to Balmond’s new book, Informal, recognizes the artistry implicit in this level of intuitive engineering: ‘through his work, engineering can now enter a more experimental and emotional territory; if architecture ever wants to evolve beyond the ornamental status it currently enjoys, it is through the thinking of Cecil Balmond and others that new seriousness and new pleasures are offered’. How logical, then, that as art practice edges hungrily into other territories, so other disciplines look to art as the next arena in which to evolve. Kapoor, of course, isn’t the first artist to take on architecture with boxing gloves in an attempt to co-opt the power that architectural scale can offer. Think of Christo and Jeanne-Claude with their wrapped buildings – the transformation of the built edifice into the cloaked and unfamiliar sculptural object. But there is something differently subversive about the fact that Kapoor’s piece lies like a waiting rocket inside the vast hall of Tate Modern. ‘Yes, it has an almost viral presence’, he admits. Rather than disguising architecture, Kapoor offers an alternative – sensory space? – to architecture. Just as architects could be said to think that spaces can alter people’s experiences, Kapoor believes that his work effects similar transformations on those visiting his installation. I’m not sure that the sculptor Richard Serra shares Kapoor’s confidence about art’s ability to take on architecture on its own terms. ‘Architects are higher up in the pecking order than sculptors’, he is reported to have said in an article in The New Yorker magazine in August this year.

Think of Serra’s vast metal sculptures, with their emphatic weighty mass and the codicils that the artist sometimes places on their location and total immobility, and you realize how polarized the debate about sculpture is. If Kapoor’s installation presents a critique of the semi-totalitarian imperatives of modernism, then recent architectural projects like the pavilions created by Daniel Libeskind, Toyo Ito and others for the Serpentine Gallery, London, reveal a desire to acquire the nimble quality of art. That these pavilions are temporary and experimental in nature breaks the permanence associated with big-name architecture, allowing the architects to play with ideas that might not otherwise be realizable. The fact that the structures can be uprooted and, with some adroit packing, be exhibited elsewhere (and they are ‘exhibited’ rather than ‘built’, one feels) begs the obvious question: are they installations or architecture? Or is it more the case that the notion of functionality itself is changing, with the idea, in the Serpentine Gallery’s case, that a rapid turnover of site-specific architecture is more interesting than a permanently entrenched building – that, in effect, architecture is worn like fashion. Kapoor’s choice of title for his work reminds us that savage competitiveness at a high level does exist in the arts and has real, painful consequences for those who take part. Whether or not Kapoor will take the next step and produce a space that can stand alone outside a building remains to be seen. Will it be judged as sculpture or architecture, or just as ‘mere’ symbol? Frank Gehry may have the answer.