In fact, as Drew shows convincingly in his book, Utzon was the unanimous choice of the judges, having already impressed the chairman, the English architect Leslie Martin, before Saarinen even got to Sydney.

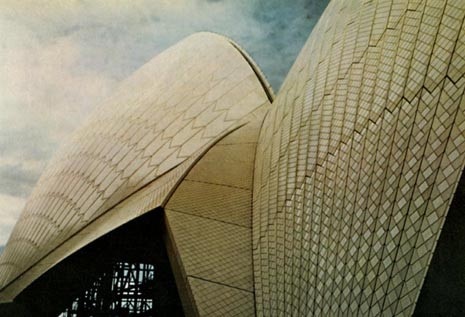

It’s hard to know why the Utzon story holds such a continuing fascination for the British press. Certainly Sydney’s iconic status has something to do with it. The Opera House, a little like Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia, has become one of the few pieces of architecture that it is OK for people who can’t stand contemporary architecture to like. The tragic aspects of the story – handsome Dane packs his bags after taking a principled stand against the philistines, never to return to see his masterpiece completed – has an undeniable pathos. But the same British newspapers that now praise Utzon are still ready to vilify the memory of Enric Miralles, even though the cost escalations of his Edinburgh parliament building still look modest beside the Opera House’s runaway budget.

Nobody can question that Utzon was badly treated. But the exact nature of the series of events that led to his leaving Sydney and losing control of the project is still far from clear. Utzon had not fully worked out how to complete the opera house at the time of his row with the New South Wales government. And he had a stubborn reluctance to accept the sensible advice of Ove Arup on how best to handle the complex geometry of the interior.

Utzon seems to have made the gesture of resignation in an attempt to get his way, without realizing that it would be accepted. Drew suggests that Utzon was very short on money, owing taxes on his fees in both Australia and Denmark, which left him little room for manoeuvre.

The reassessment of the Opera House began not so much as an attempt to reinstate its architectural integrity, but because of long-standing doubts about its acoustic qualities. Richard Johnson, the Sydney architect who will lead the project, was commissioned to come up with a solution, and wisely began by talking to Utzon. Apparently Utzon was happy to collaborate, once the lingering issue of unpaid fees dating back more than 30 years had been settled.

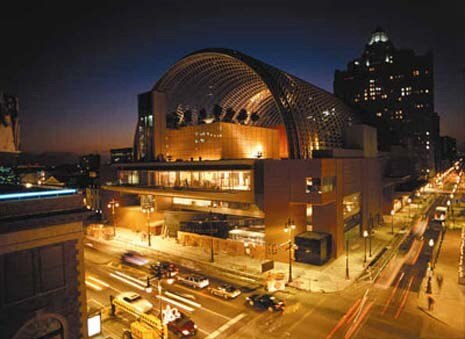

Flawed acoustics are also at the heart of Suzanne Stephens’ acid-dipped account of Raphael Vinoly’s recently completed concert hall in Philadelphia, published by Architectural Record. She reminds us that though a new building was first mooted in response to the long-standing belief that Philadelphia’s original classical concert hall was too acoustically dry ever to be truly satisfactory, the city’s wealthy donors were actually after something rather different for their money than improved musical reverberation. The project was originally entrusted to Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, whose home turf is, after all, Philadelphia. They came up with a dignified, modest and economical design. But fund-raising stalled.

They were asked to design something a little glitzier and even a little more expensive. They obliged, but evidently it was still neither expensive nor glitzy enough. They were replaced by Vinoly, a man whose father was a noted conductor and who keeps a grand piano in his office, and the resulting design can only be called flamboyant. Stephens likens it to Ledoux at roof level, and WalMart at the street.

Still no news of a solution to the difficulties of Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art. Raphael Moneo – an architect who incidentally spent a year working for Utzon on the Sydney Opera House – finished the building only five years ago, but now it has had to be evacuated after an outbreak of fungus that some people blame on an attempt to be too green with the museum’s air-conditioning system. Both the museum and the associated Swedish architecture centre have moved out, and they still do not know when they will be able to return.

In Vienna, Greg Lynn is the surprising choice to replace Hans Hollein as professor of architecture at the Hochschule für Angewandte Kunst. Despite strong support for Winny Maas and Dominique Perrault among the faculty, Lynn, who has built hardly at all, is about to get tenure for life.

Stone: Origins and Future in Architecture

On June 12 and 13, 2025, IUAV University of Venice will host "Stone is…," an international forum entirely dedicated to natural stone. Organized by PNA, this event aims to thoroughly explore the material's enduring value and sustainability, featuring insights from internationally renowned speakers.