Evaporation, photosynthesis and percolation. This year in the Danish Pavilion, designed by Copenhagen-based Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects and curated by Marianne Krogh, water – the rainwater of Venice – is the true and only protagonist. The architects, famous for their student dormitory in Tietgen (2007) and the Royal Danish Playhouse (2008), have overturned the pavilion in the Giardini, transforming it into a place where the liquid element combines environmental awareness and conviviality in a continuous, circular flow.

What is the main topic the Danish Pavilion this year?

This year the topic of the Danish Pavilion Water is Con-nect-ed-ness explored through the element of water. In the pavilion, we seek to make the circulation of water visible as a way of demonstrating how everything is connected. Water exists everywhere on the planet in a dynamic system that the exhibition in the Danish Pavilion connects to by collecting rainwater from Venice. Water is invited in, staged, sensed, and then flows out of the pavilion again. While exploring the various spaces of the exhibition, visitors can become part of the cyclic system by drinking a cup of tea brewed with leaves from the lemon verbena plants in the pavilion – that absorb water from the cyclic system. Through living bodies, evaporation, photosynthesis and percolation, people and water engage in a mutual process: we meet and influence each other in an immediate sensory experience which can help us see our own place in the greater whole.

Could you describe your project in a nutshell?

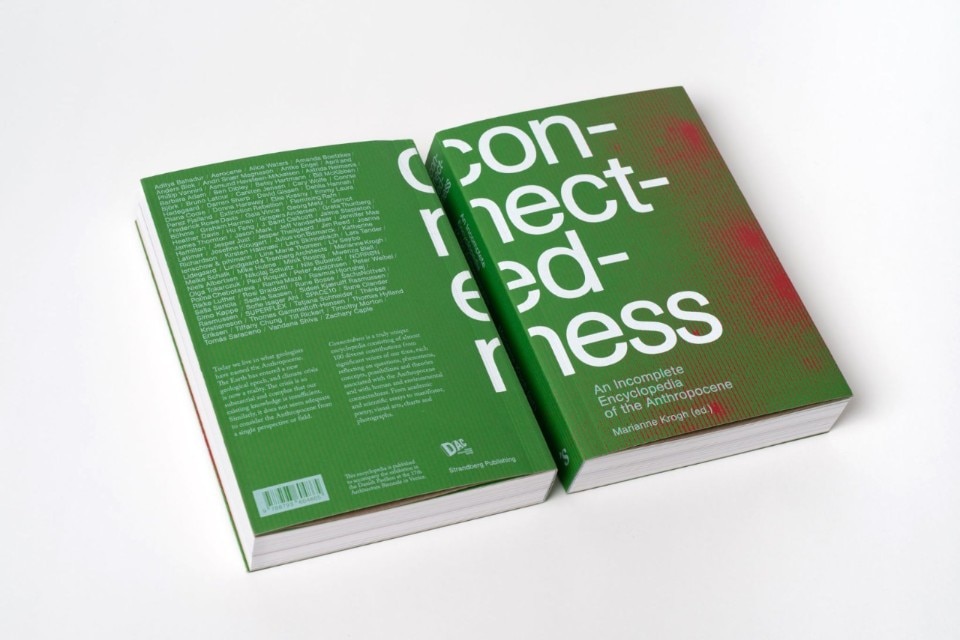

To answer, we would like to quote Josefine Klougart: “When we speak, we are nature speaking; when we think, we are nature thinking; when we subdue nature out there, we are nature subduing something inside ourselves.” (Connectedness – An Incomplete Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene, 2020)

Why did you use water?

Water is the foundation which we all stand upon and the amount of water in the world is constant. The water you drink today may have run through a river in Alaska 20 years ago. In this way the cyclical flow and inherent boundlessness of water ties past, present and future together, and rules out any possibility of isolating ourselves from each other. The water carries time, disaster, life, the others. It flows through our shared spaces. Therefore, water is a very potent ‘material’ when you seek to explore the theme of connectedness.

Connections with other people, other fields of expertise, with the built environment, nature and the larger world all form the basis of our practice.

What materials did you use and why?

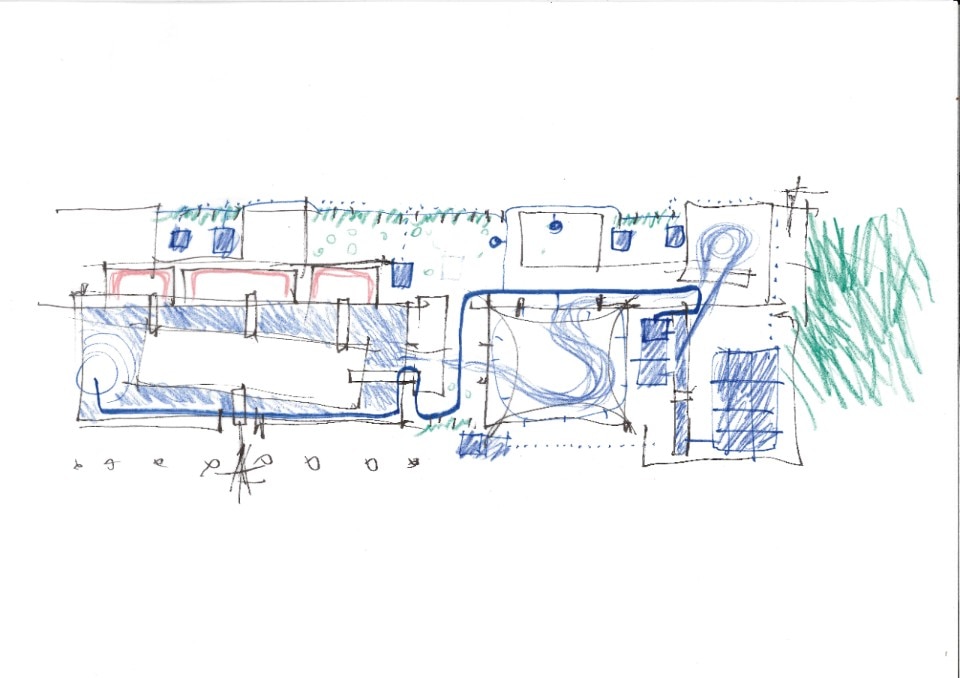

Water is the pavilion’s primary material. Furthermore black, orange, and transparent PVC water pipes and white polyethylene water tanks are used for the exposed water circuit that runs through the whole pavilion. These standard materials come with their own machine-aesthetic that contrasts the pavilion exterior and interior spaces. We used local untreated pine wood for the kitchens, platforms, and footbridges and for the trellis screens that support the planters. The warmth of the material works well with the rough concrete floor and the white walls and ceilings. In order to create the flow of water on the floor of the Koch building, we employed a thin layer of ferrocement on a build-up of prefabricated polystyrene blocks that ensure the right topography for the water stream on the floor. In the almost cubic Koch Hall we used a white suspended fabric sheet that collects water that is sprayed from the circuit pipes above. We were early on quite intrigued by this element as a spatial compressor, though quite transparent at the same time, almost like a cloud. In the large Brummer Hall, a place for both interaction and contemplation, a silver-grey material covers the walls, the niches and welcomes visitors at the entrance of the space with a soft gesture against the black piping. The pink fabric that covers the sofa cushions also contributes to the ambiguity of comfortable homeliness against the unsteadiness of the detached floor in the middle.

What is the meaning of Con-nect-ed-ness for you as architects and in your practice?

Connections with other people, other fields of expertise, with the built environment, nature and the larger world all form the basis of our practice. Engineers, landscape architects and artists are just a few of the professionals we connect with in our work. And on another level, creating spaces for meaningful, social interaction between people is at the root of our practice. Furthermore, when we build, we connect with nature’s resources and we need to be very aware that this is done responsibly. On an even larger perspective, our buildings are made to last hundreds of years, in this way we also establish connections with future generations.

In the book Con-nect-ed-ness you wrote that you like to imagine that you, as architects, make yourselves available as interpreters and storytellers. Could you tell me how? And could you make a built example (among your projects) of this kind of attitude?

When we, as architects, begin a new project, we encounter a place for the first time. It could be an undisturbed natural setting, an abandoned railyard, or a building destined for transformation. We always encounter something, never nothing. Every site has its own atmosphere and history. Often, it is grand and overwhelming; other times it may initially prove elusive. But if we continue to listen, every site, sooner or later, begins to speak. The site always dictates the outcome, we never seek to impose something that is not rooted in the site. In this way we reveal, interpret, and add new stories to what already exists. The Playhouse in Copenhagen is an example of how the old warehouses along the harbour front dictated the heavy volume of the building that accommodates the grotto-like performance spaces. Furthermore, the building evokes and enhances the location by the harbour front through a wooden promenade that encourages people to spend time and sense the water. In addition, the building itself is made for storytelling through the world class performance spaces that are designed specifically to accommodate the spoken word.

How can you as architects contribute to improve people’s connection with each other and with nature?

When we engage with a place, our goal is to generate life. It is inherent in our role as architects to be creators of the new and facilitate social interaction between people. Not so long ago, with this goal in mind, we designed a school situated between urban Copenhagen and a large, protected nature reserve. A structure of concrete rings defines a cluster of spaces that is occupied throughout the day by both children and adults. Intuitively, the children may understand the circular structures of the atrium as trees encircling a clearing in a forest. Hopefully, they experience a sense of calm when they touch the columns, experiencing the cool, pleasant surface of concrete cast in smooth formwork. As they play over the course of the day, perhaps they follow the rays of sun traversing the spaces, reminding them of the way light falls in a natural landscape. Although a school is a constructed space that provides better shelter from the elements than a woodland clearing, they both provide similar fundamental experiences of spaces and their interconnectedness. If children can realize a sense of self in relation to their physical surroundings, these experiences may stay with them and inspire how they perceive the world for the rest of their lives.

How important is the relationship between architecture and nature in your practice?

It is our basic premise that architecture always relates to nature, even when nature is out of sight. Nature is the foundation for life itself, nature is energy, rhythm, balance. When we build, ideally, people can sense this: perhaps in the way the building volumes condense and expand, the way the light flows into a space or the sensation of natural materials against the skin. The connection can be vibrant, enabling us to get in touch with the constant change that is nature’s premise and with the world’s interconnected natural cycles and systems.

How will we live together and together with nature in the next future?

The first step to imagine how we will live together and connect with nature in the future is to (re)describe, clarify, uncover and in this way reach a common understanding without distancing ourselves from each other. In our efforts to control the world, we have for centuries broken it down into different parts with little interest in sensing the connection between the parts or for that matter take responsibility for our actions. When it comes to creating a new foundation for our life together, architecture holds a unique potential. In the pavilion, we seek to make the circulation of water visible as a way of demonstrating how everything is connected. This exposure is a step on the path to an immediate sensory experience, an experience of interaction with other people which can help us see our own place in the greater whole.