Little less than ten years ago, under the lens of director Malik Bendjelloul, two South African men hit the road on the traces of Sixto Rodriguez, a 1970s American political troubadour who, despite becoming a cult artist in South Africa, had remained completely obscure in his own country.

The story became the plot of the Oscar-winning documentary Searching for Sugar Man, but mostly turned into a paradigm for the stories of all those characters who, although renowned in specific geographical areas, for some reason remained undiscovered in the West. To this category could soon be added Yugoslavian architect Svetlana Kana Radević.

Born in Montenegro in 1937, Radević – or Kana, as she goes by in her country – has been one of the most influential architects of the late Yugoslavian modernism. Above all, though, Kana has been a woman able to challenge both gender and geographical boundaries in a world that relied on (physical and ideological) borders. Kana was a female exception in an industry dominated by men, but also an elusive architect able to win awards and to conceive projects iconic for the history of Yugoslavia. However, she left a scarce biography and many questions behind her.

It is Montenegro to cast a light on this story with an exhibition at Palazzo Palumbo Fossati as part of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Curated by Dijana Vucinic and Anna Kats, “Skirting the Center: Svetlana Kana Radević on the Periphery of Postwar Architecture” draws on the extensive and mostly unseen graphic and photographic archives of the architect who passed away in 2000 with the aim of joining the dots and let the world (re)discover one of Montenegro’s most brilliant architects.

Born in the capital Cetinje, Svetlana Kana Radević grew up with the familiar sight of post-war urban scenarios, therefore developing a sensibility – perhaps an intrinsic necessity – for a new architecture that unfolded under the fruitful bridging of soviet brutalism and Panamerican modernism. The knowledge matured, in full Cold War swing, by a Yugoslavian architect on themes such as American home design or the public opus of Niemeyer in Brasilia should perhaps surprise, but it actually doesn’t.

It’s in the cracks of history that individuals’ own lives and stories slide in, giving birth to cultural crossovers and narrating about society – and, as a consequence, about architecture – beyond political doctrines and official historiography.

That is the case of Kana’s life, in fact. Told through sketches, drawings of projects, amateur photographs, Polaroid snapshots, Super8 films, typewritten letters, badges, and other personal documents, her life acquires the traits of an intimate portrait, hence a human and tangible one, of an architect who, for too long, was linked to the officialdom of state representations.

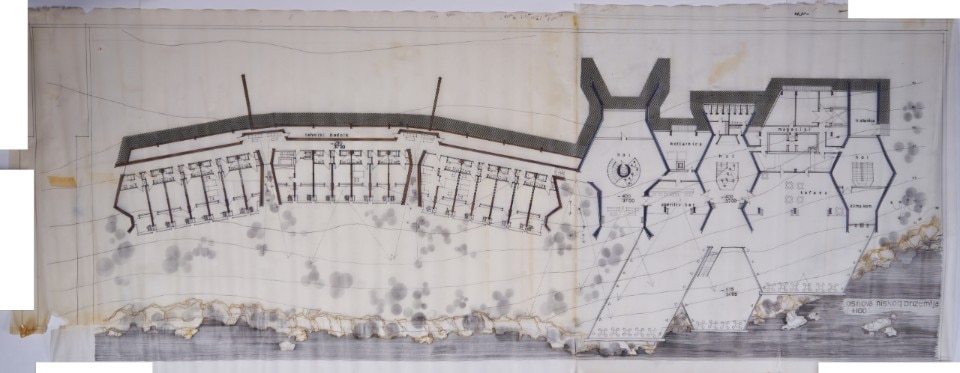

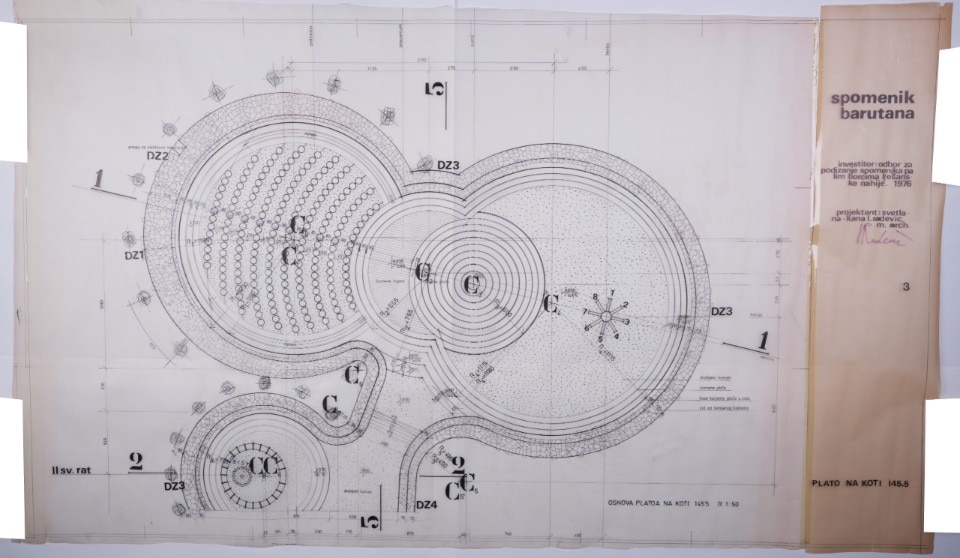

For sure, many are her militant opuses, like the spomeniks, the monuments celebrating the regime’s politics and the war memorials (see the Monument to Fallen Fighters in Lješanska Nahija, Barutana Podgorica), yet several are also the works influenced by a transnational feeling, a sign of an architect interested in the evolution of the subject and in constant equilibrium between Eastern and Western culture.

There lies the point that allows us to deeply understand – or, perhaps, it sets the toughest of questions – the persona and the production of Radević. One example, above all, is the Hotel Podgorica, a building that establishes a mediation between the Yugoslavian aesthetics and the modernist sensibility of post-war Brazil with its severe but sinuous facade that unfolds following the trajectory of the Morača river, on whose banks it was built.

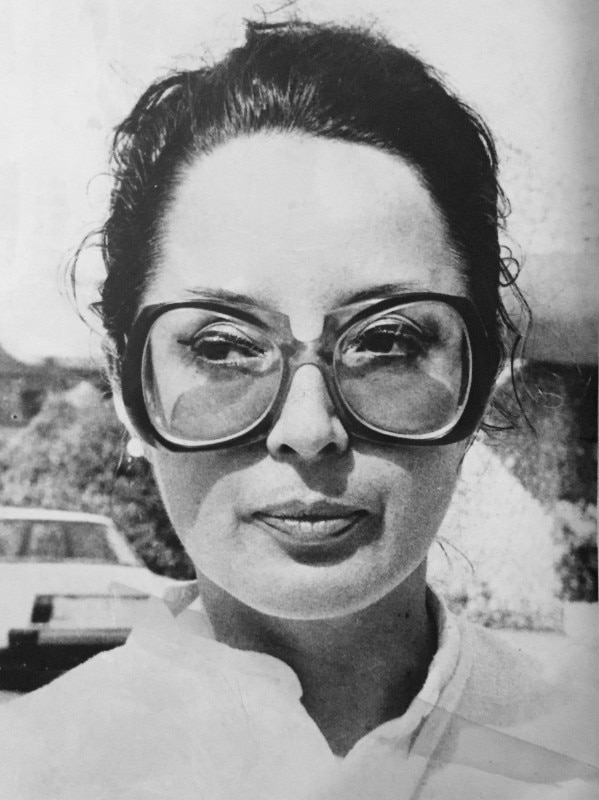

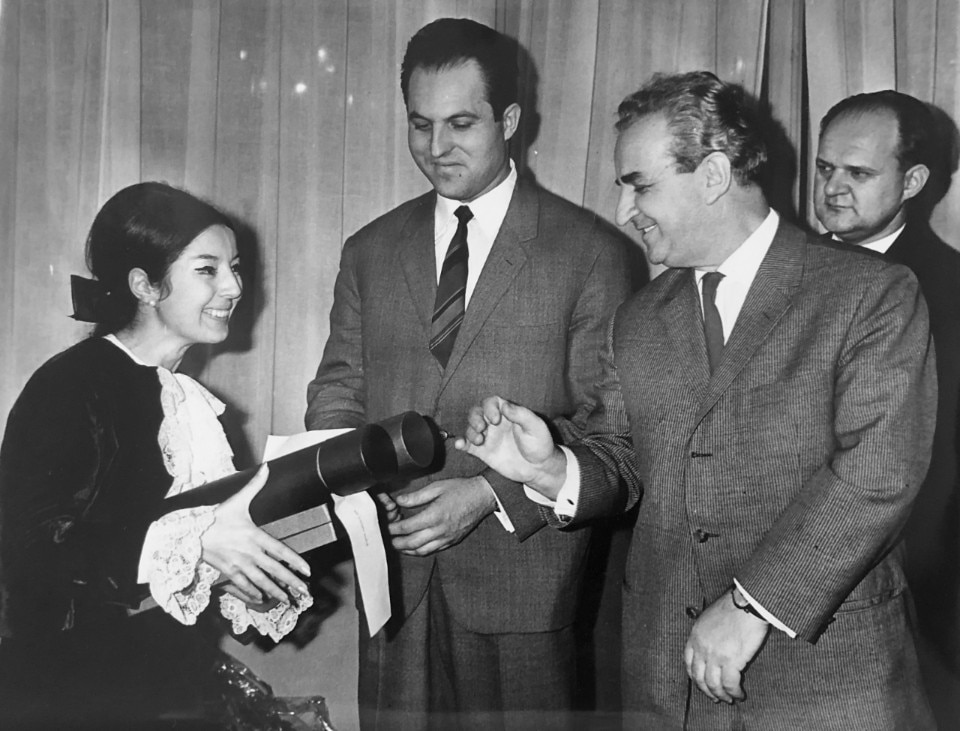

After graduating in architecture from the University of Belgrade, with the Hotel Podgorica Kana won herself, even before its inauguration, the cover of Arhitektura Urbanizam magazine and the 1967 Federal Borba Prize. At the young age of 29, Radević showed up collecting the most prestigious award in Yugoslavian architecture looking like a dandy Bond Girl: a dark velvet twinset and a ruffle shirt with enormous and wavy lace cuffs. An image that clashed with the sober all-male board of the event and, mostly, with the autochthonous culture, surely vibrant but tied to the regime’s bonds.

It is in the distinctively personal curation of her image, that combines the femineity and aesthetics of the architect to those of her projects, where Kana’s uniqueness lies. An archi-star before the birth of the concept itself, a pop icon despite not joining any anti-architecture movement.

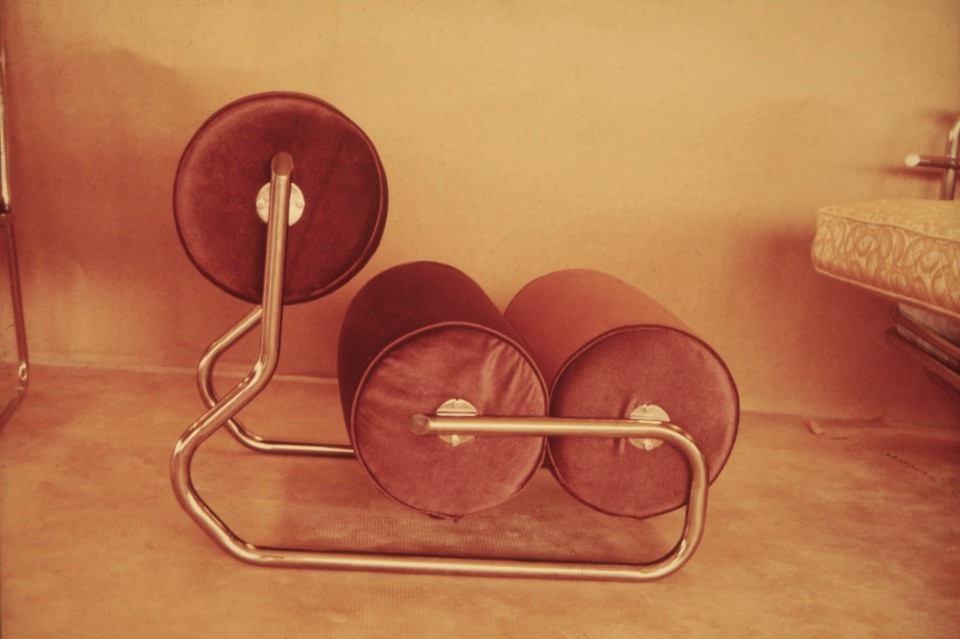

The amateur photographs that keep trace of her projects – like the snapshot of the Lily chair inside the Hotel Zlatibor – highlight the candid image of a human being before that of an architecture professional. The material on display showcases Radević's forward-thinking dedication in the curation of a personal iconographic archive decades in advance of the advent of social media.

The international – and perhaps feminist – vocation of Radević is manifested, beyond her aesthetics, by her attendance, from 1971 to 1973, to Louis Khan’s Master Class at the University of Pennsylvania, where Kana is one of the only 16 students to graduate from the course in its 19-year run. A programme of studies in which the Montenegro architect showed, like a former university alumnus recalls, “intellectual maturity and philosophical inclinations”; qualities that won her a Yugoslavian bursary to attend a doctorate under Khan’s supervision.

In 1977, though, the funding gets mysteriously cut, the biographical information turns vague, and Kana disappears from Philadelphia. She’ll reappear in her homeland, to then move to Japan where she works for the atelier of Kishō Kurokawa, although still keeping herself busy in Montenegro, where she sets up a studio that remained operative until the 1990s.

In 1977, though, the funding gets mysteriously cut, the biographical information turns vague, and Kana disappears from Philadelphia. She’ll reappear in her homeland, to then move to Japan where she works for the atelier of Kishō Kurokawa, although still keeping herself busy in Montenegro, where she sets up a studio that remained operative until the 1990s. There she works on projects like the Hotel Zlatibor (1979-81), for which Kana works on its interiors by conceiving the Lily chair, another element that allows us to uderstand her knowledge in matter of modernist design, of Western club interiors and also her intuitions on the early stages of post-modernism.

In her return to the motherland comes up the syncretism of the philosophy and work of Radević, an architect and a woman with a strong international vocation, but at the same time a disciple – who knows how militant in her intimacy – of Soviet culture.

While in the Biennale gardens one can spot, glorious but dismissed, the shut down and abandoned Yugoslavia pavilion, the exhibition curated by Montenegro works, without nostalgic feelings of sorts, in reminding us how heritage and contemporaneity can dialogue with each other through the intimacy of archives and the officiality of the ideas of Svetlana Kana Radević, a no longer oblivious bridge between the Western and the Eastern bloc.

The free exhibition “Skirting the Center: Svetlana Kana Radević on the Periphery of Postwar Architecture” runs until November 21st at Palazzo Palumbo Fossati, Venice.

Opening Image: portrait of Svetlana Kana Radević. Photo: Svetlana Kana Radević personala archive.