Reinhold Martin, University of Minnesota Press, 2010 (248 pp., US $25)

The economist John Kenneth Galbraith wrote that familiarity and predictability were marks of acceptable ideas, or what he defined as conventional wisdom. For Galbraith, the enemy of conventional wisdom was not ideas, but the march of events. The interaction between the power of shared perceptions and attitudes and visible actions forms a core of Reinhold Martin's Utopia's Ghost: Architecture and Postmodernism, Again. In approaching relatively recent events in architectural culture, Martin suggests that using the tools of historical analysis might be inadequate or premature. Instead postmodernism—perhaps unfashionable for being "not either too late or too early"—can be used to "emphasize a set of concepts that were reworked as a consequence of that turn." Instead of doing history, Martin looks for the history in familiar touchstones of architecture such as Learning from Las Vegas, Peter Eisenman's encounters with Chomsky's linguistics, and the mirrored facades of Philip Johnson's buildings for oil companies.

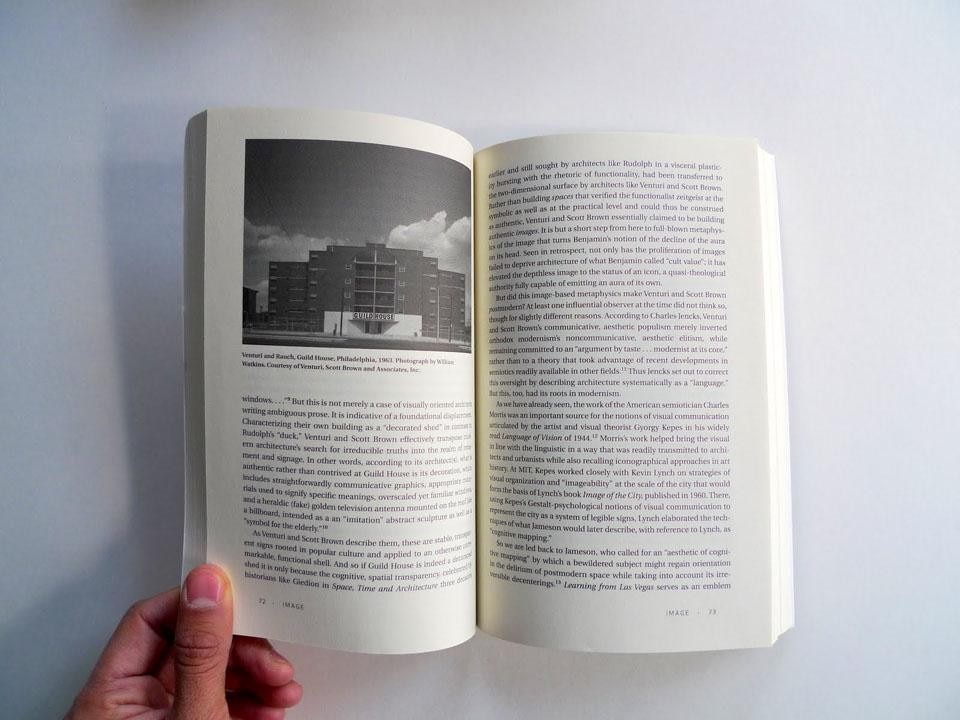

What he finds in his examination is a denial of architecture's complicity with power and politics coupled with a "sullen withdrawal from engagement, or (what amounts to the same thing) the preemptive, exuberant embrace of the status quo." Though he claims what might "be most postmodern about architectural thought…is not its verifiability in practice, but its status as a mode of production in its own right," Martin's focus often centers on buildings. A detailed description of the "two dark, crystalline solids" of Pennzoil Place in Houston designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee leads into an extended mediation on the relationship between architecture, materiality, and capital. For Martin the "oil" in Pennzoil becomes a network of relationships constituted by a "hybrid plurality of objects" including the chemical itself, industrial organization, finance, geopolitics, and other elements of dubious standing that come from even a cursory investigation if anyone in architecture had the nerve.

Thirty years ago Carl Schorske described the culture of fin-de-siècle Vienna as defining itself "not out of the past, indeed scarcely against the past, but in independence of the past." We have no such luxury of independence. While Martin claims that he is not offering a history of postmodernism, but rather a "historical reinterpretation of some of its major themes," he ultimately offers history as a powerful tool for analysis rather than stasis. The reinterpretation often highlights architecture's failings. But the value of such analysis is that it holds the possibility of transcending those failures, or in Martin's words to learn "to think the thought called Utopia once again."

Pollyanna Rhee was educated at Wake Forest University and at Columbia University where her teachers included Reinhold Martin.

Instead of doing history, Martin looks for the history in familiar touchstones of architecture