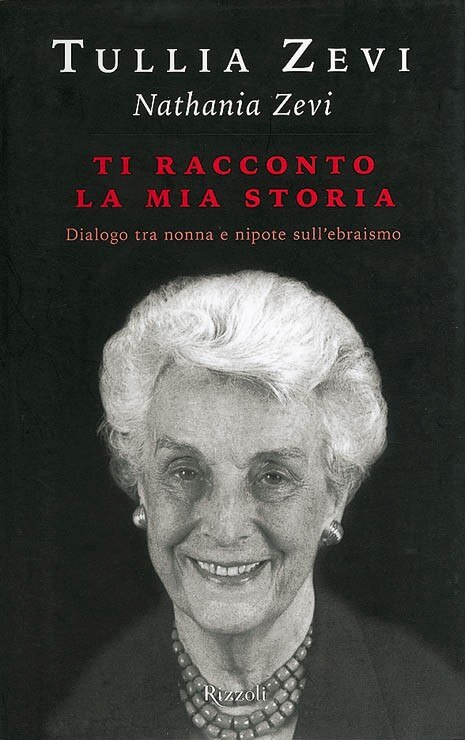

Ti racconto la mia storia. Dialogo tra nonna e nipote sull’ebraismo, Tullia Zevi (con Nathania Zevi), Rizzoli, Milano 2007 (pp. 148, € 16,50)

Zevi su Zevi. Architettura come profezia, Bruno Zevi, Editrice Magma, Milano 1977; Marsilio, Venezia 1993 (pp. 246)

“I liked him as soon as I set eyes on him. I was struck by his intelligent eyes and the sound of his voice. The engagement lasted six months but the incantation less – he was a difficult, explosive and highly-strung man, the only male son of a traditional family and totally spoilt. I was plagued with doubt. He talked so much and I remember going for long walks, from which I would return completely dazed. He could hold long soliloquies lasting up to eight hours without interruption that left me fascinated but exhausted. As soon as I opened the front door he would explode, ‘I can’t do it. I can’t stand it any more’… The first time I tried to break it off was because he seemed such a hard man to live with and I was afraid I couldn’t do it for a whole lifetime. But I was drawn to him and fascinated by his intelligence, his civil passion. One fine day, my father saw me crying and was overcome by a sudden fit of paternal love, saying to me, ‘I tell you he is mad and madmen frighten me’… This continued for a while; I would break off the engagement and then go back; I married him in the end.” (p. 42-43)

“Two days after arriving in New York, I went to a night meeting in Franco and Serena Modigliani’s home with a dozen or so young people who had been in America just a few months. I spoke about the situation in Italy and described the ‘new anti-Fascism’. There was a girl there. I didn’t know her name and we didn’t exchange a single word; we may not have even shaken hands. In short, I ‘knew’ she would be my wife. No overriding passion, no irrational actions or overflowing emotion – something for which I was subsequently often reproached. I felt a more noble and solemn sentiment than attraction: that of a common destiny. The next day I asked Cagli to read the tarot cards. I chose a card, a symbol, for her and one for me. Sitting pensively on the fl oor, Corrado lay the fi gures down at slow intervals. After completing the operation, he remarked with wonder that the second card had not appeared: ‘It seems strange but you will never meet her again, whoever she is.’ I left for Cuba to obtain a residence visa; in the meantime I had learned that she was Tullia Calabi, Jewish and from Milan. I wrote her a long letter in the La Habana hotel… We met up again in Central Park, I gave her the letter, or rather I read it to her, and we decided to get engaged. I felt as if I was reciting a stranger’s part, with a foregone conclusion. I wanted to involve her not in a love affair but in the things that come after years of marriage: studies, work, the torment of empathy, the outbursts and the depression, self destructiveness and the desire to be true rather than happy. Our engagement was abruptly interrupted twice, which hurt us both. Tullia was adamant and sought with all her might to avoid a destiny that, as she saw it, was not the product of love… We arranged to get married in the Spanish-Portuguese synagogue on December 26, 1940. The evening before the wedding, I told Cagli that something had gone wrong with the tarot cards and he said: ‘Let’s check.’ Once again, the two symbols did not come out together. ‘You will be husband and wife but you will never meet. Good luck!’… It is hard to gauge how much truth lay in that prophesy. It clearly referred to the overall journey not the everyday chronicle of events. Neither of us wants to say: Corrado was wrong.” (p. 42-43)

An encounter in the setting of Fascism, racial laws, exile and war. The civil and cultural undertakings that served as the backdrop to this story were a constant presence in the biographies of the two central characters: Tullia and Bruno Zevi. She is a journalist and was the first female president of a country’s Jewish community (in this case the Italian one). He was one of Italy’s most renowned architectural historians, also famous abroad. Tullia’s biography is recent, Bruno’s is older, but both express a profound ethic. Both are well written, with irony and feeling, as shown by the intimate personal memories of the two subjects – which by a surprising coincidence are to be found on the same pages of the books. A read that comes close to the canons of the discipline and thus strongly recommended.

Roberto Dulio Professor of History of Architecture at Milan Polytechnic