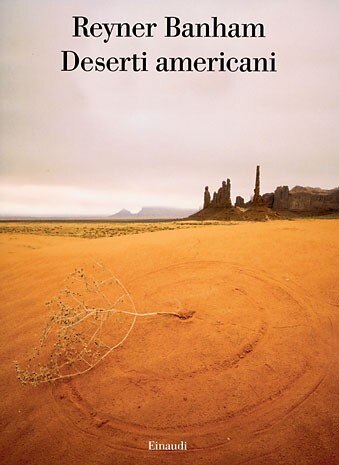

Deserti americani, Reyner Banham, Einaudi, Torino 2007 (pp. 212, € 19,00)

What is an architectural historian doing in the middle of the Mojave Desert? Here, on the border between California and Nevada, the interstate highways constitute the only urban fabric and human presence is indicated by the odd fuel pump and a couple of seedy motels, plus a road sign giving drivers the useful information: “Kelso 34 miles, no service station. Next service station 68 miles.” Driving a V8 and wearing a dirty old crumpled Stetson, Reyner Banham was travelling Interstate 15 between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, heading for sin city. It was February 1968, and like much of his generation Banham was a fan of pop culture, captivated by the flashing neon lights and host of placards for saloons and casinos in the world capital of lapsed morals that originated as a water hole on the Old Spanish Trail in the early 19th century. On the outskirts of Baker, a town with few attractions on the Barstow-Las Vegas route, he was almost forced to turn off when entranced by an atmosphere of dusty exoticism. This landscape was so different from his previous experiences that it made a lasting impression on him, and he soon became a desert devotee. The valleys crossed by Interstate 15 are on average 25 km wide, and the incommensurable spaces could not be more different from the universe filled with mildew and moors of his childhood spent in Norfolk.

There, in the Mojave Desert, crossed by the insignificant stream of the same name, Banham received his baptism of the desert, a cinematographic space even before films were invented and a favourite location of directors and writers. Many science fiction images originated there and it is where the first UFO sightings occurred and the first atomic bombs were detonated. The Kelso Depot lies a few miles to the south. This water supply station, built by the Union Pacific Railway in Spanish colonial style, offered an excellent opportunity to study the relationship between man and the arid environment. This apparently untouched, almost lunar environment also provides material for scholars. Empty wells, abandoned mines, railway architecture, service stations, hotels and inns – like the Furnace Creek Inn, a few miles west of the famous Zabriskie Point, in Death Valley, surrounded by a palm grove that gives it the natural appearance of a Beverly Hills garden. Built on the terracing of the old borax mines (a soft white crystal used to manufacture soap and detergents), it is one of the many tiny indications of man’s passage in this place that is apparently so far from everything. The inn is a sign of the recent tourism made possible by cars, but also of the decline of a once flourishing mining industry. These tiny marks of civilisation capture the traveller’s interest: a parked trailer, tyre tracks in the sand and electricity pylons. The words “The desert is where God is and men are not,” mean little to Banham, who is more intent on understanding what man has to do with the existence of the desert.

The desert has also been the imaginary location of Utopia and some of its most radical versions. It was in the Arizona Desert that two architects, Frank Lloyd Wright and Paolo Soleri, arrived at virtually opposite results after finding something very close to a blank sheet on which to trace a new beginning and fully express their fantasies of communities that were devoid of prejudice and the oppression of land ownership. Banham was conscious of the cultural baggage that he carried with him across a totally foreign territory, but was always shielded from clichés. Thanks to his very lucid eye, Banham has managed in this book to correct some assumptions on the American desert and to explode some of its most persistent myths. He is clearly concerned about how excessive processes to turn the habitat into a museum might trigger a Disney-style drift. Critical of those who seek to “rediscover themselves” in it, he is equally severe with regard to an affected eco-friendliness that seeks to embalm the desert. The book was published in English in 1982. It was the product of familiarity with the southwest American desert built up over more than ten years’ experience in the field, and has only now been translated into Italian. The Mojave Desert, the beginning and end of this fascinating tale, has been a national reserve since 1994 and the Kelso Depot was turned into a visitors’ centre in 1994.

Michela Rosso Professor of the History of Architecture in Turin