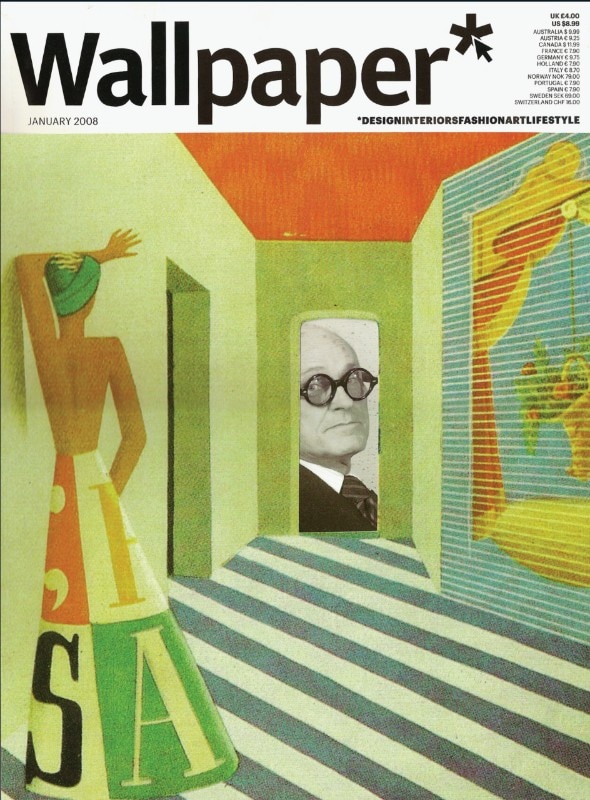

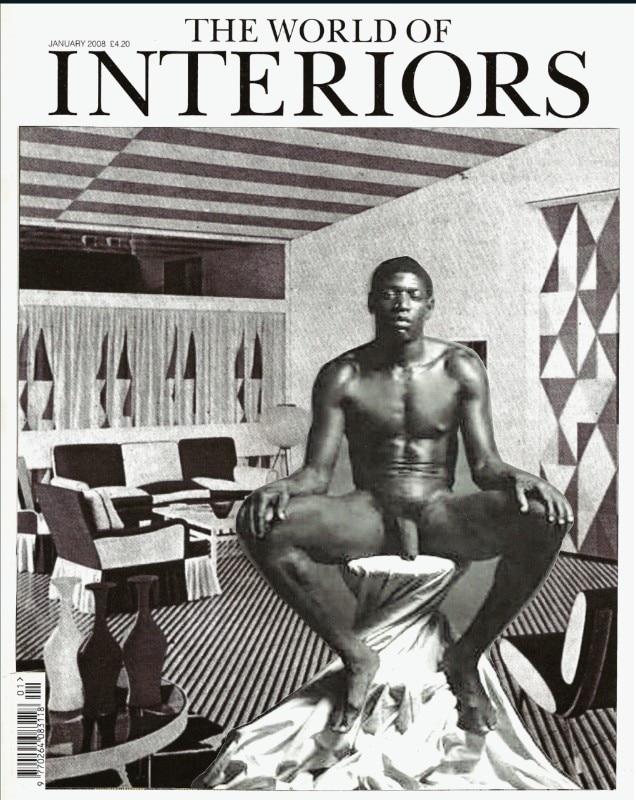

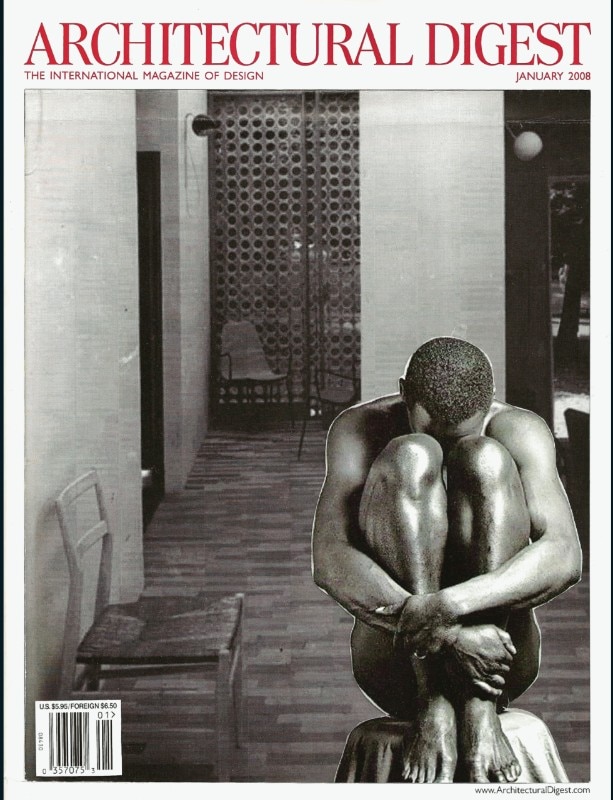

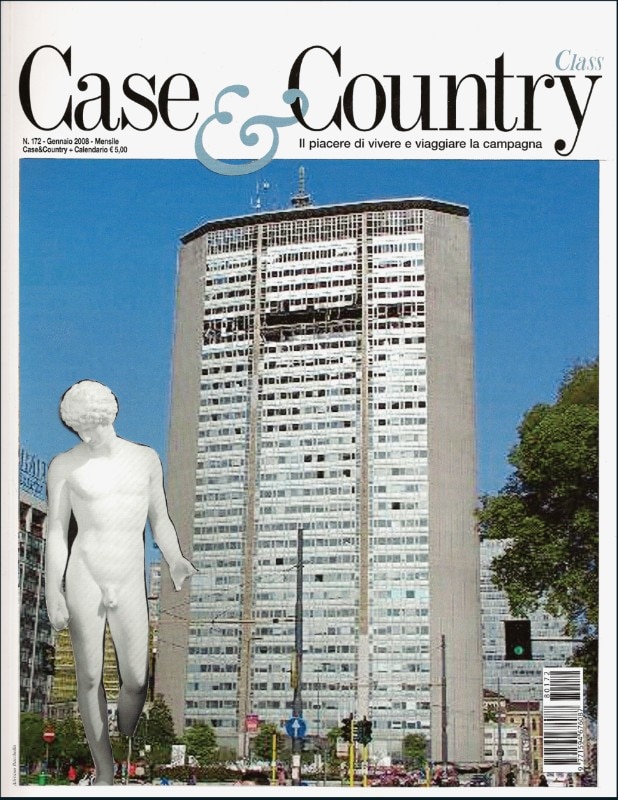

JUST WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES TODAY’S HOME SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING? collage, mixed media January 2008 © Francesco Vezzoli

Originally Published on Domus Gio Ponti / 2008

Artists were his friends and fellow travellers who followed the architect into extra-pictorial adventures, emerging from the silence of their studios to confront new spaces. Ponti played an active role as a sharp and undisputed talent scout, and deployed his discoveries in architecture or the decorative arts. He was a director of situations, an artist among artists. An emblematic case is Fausto Melotti, “discovered” while still in his twenties as a promising ceramicist during Ponti’s art directorship of Richard Ginori, and encouraged for a lifetime in his extraordinary creative adventure. Ponti chose those magic, liquid ceramics for important built works (the Alitalia terminal in New York, Villa Planchard in Caracas and Villa Nemazee in Teheran). The artist had an extra-pictorial readiness to transfer ideas into works which did not contemplate the traditional easel format, but found a new and necessary expression through “art production” and collaboration with highly skilled craftsmen and unique industrialists in Italy. This formed the basis of Ponti’s approach to figurative art: one of the “modern” principles of a renewal of the arts on which the architect founded his Domus, launched in 1928. The terms of Ponti’s “action for art” were his directorship at an early age of Richard Ginori, the Monza Biennales and subsequent Triennales; the innumerable pages of Domus devoted to plastic and pictorial developments; and actual works of architecture, clients permitting. Among the artists involved was Mario Sironi, appointed to oversee the “mural painting and decorative sculpture” section of the V Triennale in 1933. Ponti was also in regular contact with prominent figures from the Novecento movement such as Carrà, Tosi, Andreotti, Martini and Romanelli. In the early days of the Triennale he cultivated his friendship with Severini, his predilection for Funi, and his appreciation of de Chirico who, in 1941, began contributing to the magazine Stile. Meanwhile one of the principal functions of “public” art was clarified in Ponti’s mind: to rescue artists from an asphyxiating situation arising from underdeveloped collecting by the usual galleries, and from a rigidly tumultuous system of exhibitions. With Massimo Campigli, another pivotal name in Ponti’s artistic life, he carried on a long dialogue and boosted, almost by a sensitive coincidence, the “vase-women” style and that of the triangular figures. The painter was admired for his “figured abstraction” and elegant archaism, simplicity and grandeur, for the bundling of human figures into frames and windows. The vast and famous decoration of the Liviano atrium at Padua University (1939) was also the realised dream of an architecture as colour. Ponti’s promotion of original artists’ ceramics and their use in architecture made him the advocate of contemporary Italian art reborn after World War II. He understood and precociously enhanced the work of the master Lucio Fontana in relation to the ceramics of Picasso, reappraised the Albisola School (the very young Salvatore Fancello, Agenore Fabbri, Aligi Sassu), Melandri and the Faenza school, and discovered Leoncillo. Ponti’s faith in Fontana was a specific case, similar to those of Campigli and Melotti. It was to accompany him through- out his life and culminated in the frequent publication in Domus of Fontana’s extraordinary “novelties”, in the covers dedicated to him during the years of Spatialism and beyond, and in successful collaborations (as in the atrium of Via Donizetti 24, in Milan). A key chapter in Ponti’s dealings with artists was that of his furniture design for transatlantic liners, which came to resemble floating museums of Italian creativity. In his interiors for the first-class decks of the Conte Grande and of the Andrea Doria (1950-52), with Nino Zoncada, or in his prestigious designs for the Conte Biancamano (1950), lead roles were played by original ceramics (Melotti, Fontana, Melandri, Leoncillo, Fiume), and brilliant craftwork (De Poli’s enamels, Altara’s paintings on glass, the ceramics of Gambone and Rui). These were accompanied by masters like Sironi and Campigli, the established artists, with large-scale formats or tapestries, next to pictorial works by Ponti himself. Their combined efforts expressed an “integration” that was to usher in an international widening of Italian artistic horizons between abstractionism and the informal. The trend, though, was soon undermined by the birth of the designer figure, the advent of new- dada aesthetics and, in art, by the development of the concept of “environment”. The principle of Pontian “expression” attempted a dialogue with the attitudes of erasure and extreme conceptual reduction of multiplied works and of environmental art, for example at the Ideal Standard shop promoted in the ’60s in Milan (where Vigo, Pistoletto and Sottsass, among others, exhi- bited works in the series entitled Expressions). Nevertheless, by that time the aesthetic of emptiness and of a more honest rationalism had started, something which Ponti did not evade. The principle of architecture was stated as a “total” artwork and invention, encompassing the expressive functions previously “delegated” to the talents of numerous creators. Ponti’s relationships with long-admired artists, like de Chirico, Campigli, Fontana and Melotti, evolved into faithful lifelong friendships, in the name of a “higher” mission of architecture as art.

Edited by:

Paolo Campiglio

Paolo Campiglio is a researcher in History of Contemporary Art at the University of Pavia. He is particularly interested in the cross-relationships between the arts and has written various essays including Ponti artista verso gli artisti, in Gio Ponti e l’architettura sacra, Silvana Editoriale 2005.

Francesco Vezzoli

On April 18, 2002, a small Rockwell Commander aeroplane piloted by 67-year-old Swiss-based Luigi Fasulo arrived at around five pm over Milan from Locarno. It then flew into the upper floors of the Pirelli building, the urban icon and only skyscraper in Milan designed in 1956 by Gio Ponti. The plane smashed against the glass windows killing five people, pilot included. For a moment Italy saw its own micro 9/11. After a terrorist attack had been ruled out as well as a military strike by the otherwise neutral and pacific Switzerland, people started to wonder what had happened. The Pirelli building is hard to miss in Milan’s skyline, but also easy to avoid if there is no fog, and that afternoon there was good visibility. It turned out that the Swiss Mohammed Atta was allegedly a depressed, retired person who chose to end his life in that spectacularly pathetic and tragic way, dragging four innocent people into his own folly. None of the victims of the crash probably knew that the building was a landmark of Italian architecture and a daring feat by one of its most distinguished postwar architects. Had the outcome not been so tragic, the cast of characters might have suggested that the event had been orchestrated by Francesco Vezzoli as an art performance, happening or some kind of artistic intervention. Vezzoli’s morbid fascination with second-rate characters or faded stars resurrectedfrom a range of fields from movies to fashion and architecture could have justified a project like that one of a small plane flying into Gio Ponti’s self-made monument. In 2002 Francesco Vezzoli was not thinking in such a heroic way.

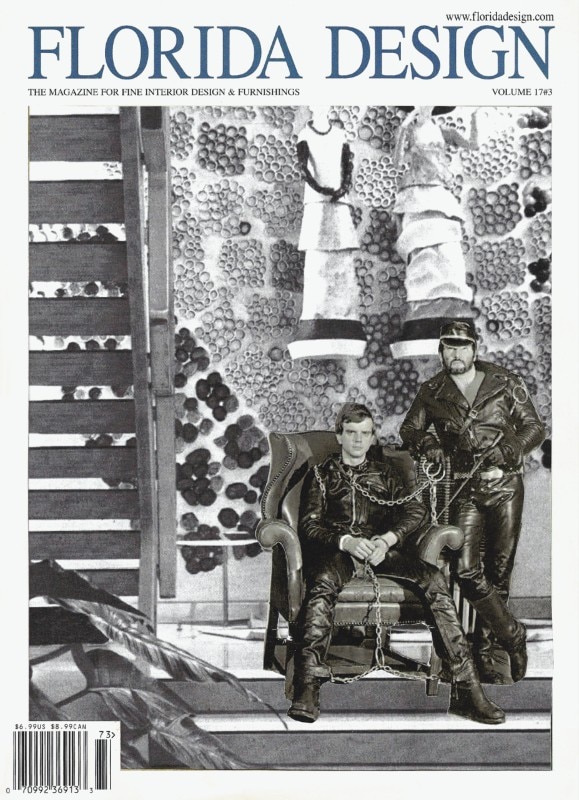

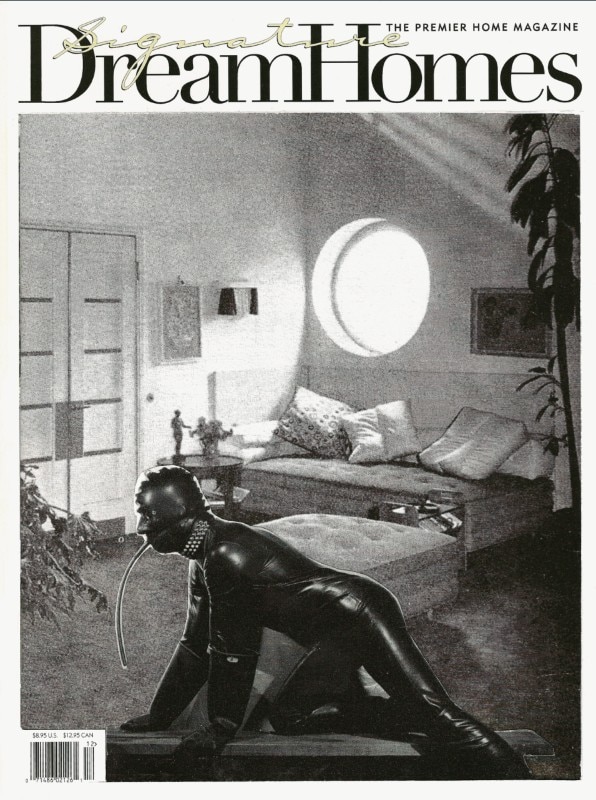

In fact, rather than turning his models into heroes, his perverse fantasy was focused on transforming them in doilies to decorate the living room of some old archetypical modernist aunt. Some people see Gio Ponti as a semi-divinity who could likely appear as a miracle or hallucination on top of the Pirelli building; Francesco Vezzoli sees him more as a saint of a lesser god who fits perfectly on top of a fake baroque cupboard under a vase of fake flowers. Icon-phobic or iconoclast, it’s hard to say in the case of Vezzoli. But his reading of Gio Ponti as the designer of the gay culture of upper-end home decorators, particularly in the United States, is quite interesting.

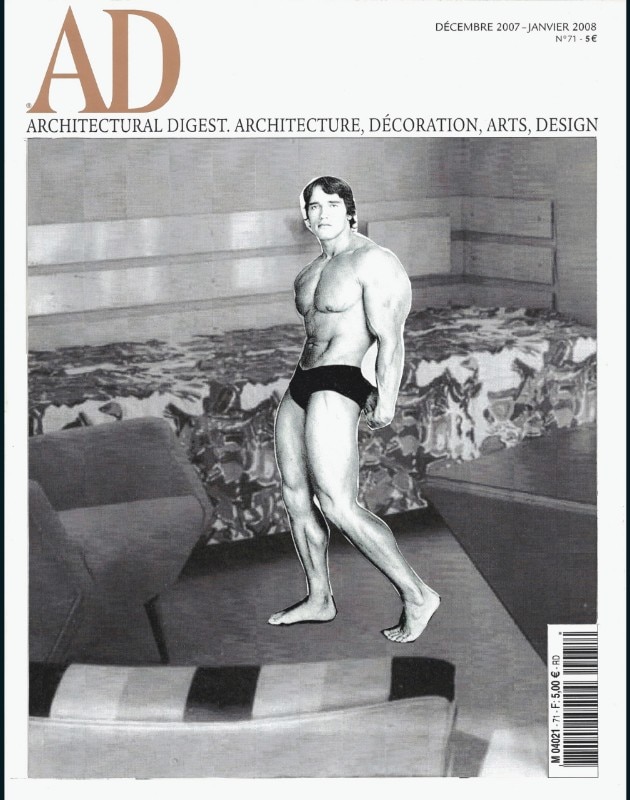

Any respectable antique dealer of modern furniture in Manhattan has a “Gio Ponti” piece. Gio Ponti is the safety net for any unnamed object or piece of furniture that looks particularly good but whose designer is yet to be discovered; “We believe it is a Gio Ponti,” is usually the answer to the puzzled expression of a client looking at the five-figure price tag hanging from a 12-inch side table. According to Vezzoli, Gio Ponti created his own international style foreseeing a taste not yet so ghettoised as it is today by gay culture. The Italian architect and founder of this magazine would have been horrified to have met people like Schwarzenegger or Robert Mapplethorpe, terrified to know their friends and partners. His idea of space would not have sustained the sexual brutally of the underworld of the late ’70s or early ’80s; his light touch magically manifested in the “superleggera” chair would have crumbled under the bodies of Mapplethorpe’s models. And yet the contrast imagined by Vezzoli is fascinating and challenging, posing very scary questions for those who see Ponti as a symbol of the soft flirtatious machismo of the Italian innovative economic Renaissance of the ’50s and early ’60s. Vezzoli’s question is basically this: “Was Ponti a closet homosexual?” In case of an affirmative answer I wonder if the closet he was hiding in had his own original signature.

Who is Francesco Vezzoli

Born in 1971 in Brescia, Vezzoli has been working on the creation of an artistic language mixing photography, video art and embroidery. By dissecting art’s iconography and the expressive matrixes of movies, literature, politics and media power, Vezzoli anatomises the way they influence our collective vision of the world. His work has been exhibited at the Whitney Biennial,

the 49th, 51st and 52nd Venice Biennials, Guggenheim Museum, Tate Modern, Fondazione Prada and Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin.