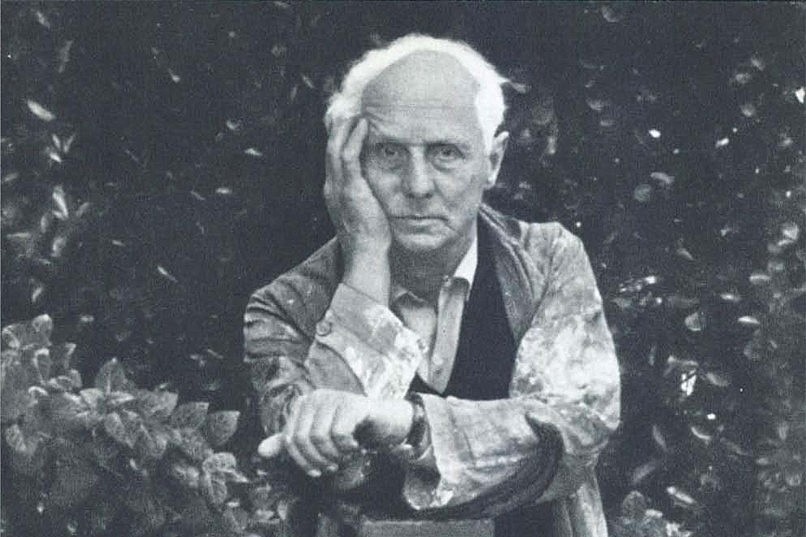

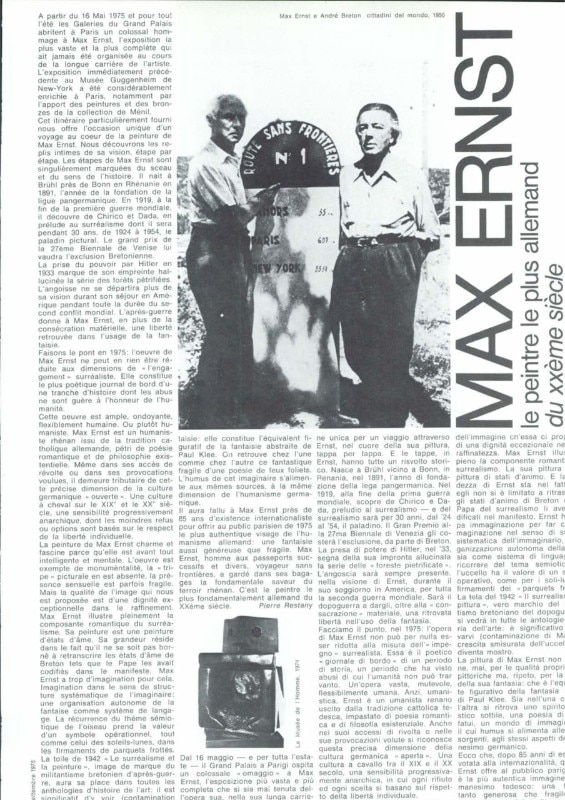

Few artists, perhaps none, have succeeded as well as Max Ernst in plunging deep into the tensions and anxieties of a century, then giving to such burden a form that could be shared with a wide audience. Going beyond the Surrealist label, invested in painting, sculpture and even filmmaking, creating dreamlike triumphs such as “The Antipope” and “Attirement of the Bride”, of the enigmatic frottages of the “Histoire Naturelle”, Max Ernst has traversed entire chapters of modern art history – even spending a large part of his life with them, if one refers to Leonora Carrington, Peggy Guggenheim or Dorothea Tanning. Through this long journey, Pierre Restany could perceive the trace of the artist’s cultural roots: he wrote about it in September 1975, on issue 550 of Domus, on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to Ernst in Paris.

Max Ernst. Le peintre le plus allemand

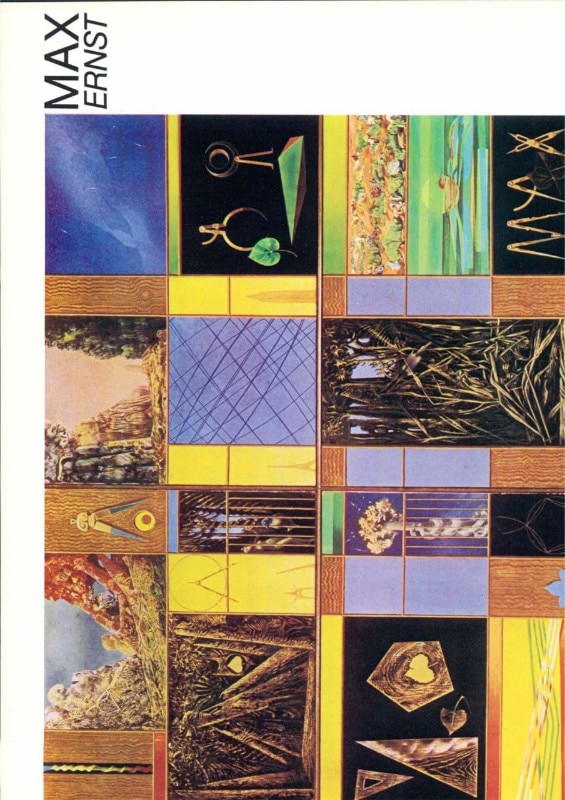

From 16 May 1975 and throughout the summer the Galeries du Grand Palais in Paris house a colossal homage to Max Ernst: the biggest and most complete exhibition ever organized during the artist’s long career. The exhibition held immediately before this one, at the Guggenheim in New York, has been considerably enriched in Paris, notably due to the addition of paintings and bronzes from the De Menil collection.

This particularly dense itinerary affords a unique opportunity to travel into the heart of Max Ernst’s painting. The innermost recesses of his vision are unfolded, step by step. These stages in the development of Max Ernst’s art are singularly stamped with the seal and the sense of history. He was born at Brühl, near Bonn, in the Rhineland, in 1891, the year the Pan-Germanic league was founded. In 1919, at the end of the First World War, he discovered de Chirico and Dada, as a prelude to Surrealism, of which he was to become the champion painter for 30 years, from 1924 to 1954. His first prize at the 27th Venice Biennale led to his subsequent exclusion from Surrealism by Breton.

Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 is marked by the hallucinated tone of Ernst’s series of petrified forests. This anguish pervaded all his work during his stay in America and throughout the Second World War. The postwar years brought Max Ernst, in addition to material consecration, a new-found freedom in the use of imagination.

The point reached in 1975 is this: Max Ernst’s oeuvre cannot in any way be reduced to the dimensions of a Surrealist “commitment”. Rather, it constitutes the most poetic log-book of a slice of history whose abuses hardly do honour to mankind. This oeuvre is broad, undulating and flexibly human. Or rather, humanist. Max Ernst is a Rhinelander humanist descended from the German Catholic tradition, steeped in romantic poetry and existential philosophy. Even in his outbursts of revolt or deliberate provocations, he remains a tributary of this clearcut dimension of “open” Germanic culture, poised between the 19th and the 20th centuries, with its progressively anarchic feeling whose slightest refusals or options are based upon a respect for individual liberty.

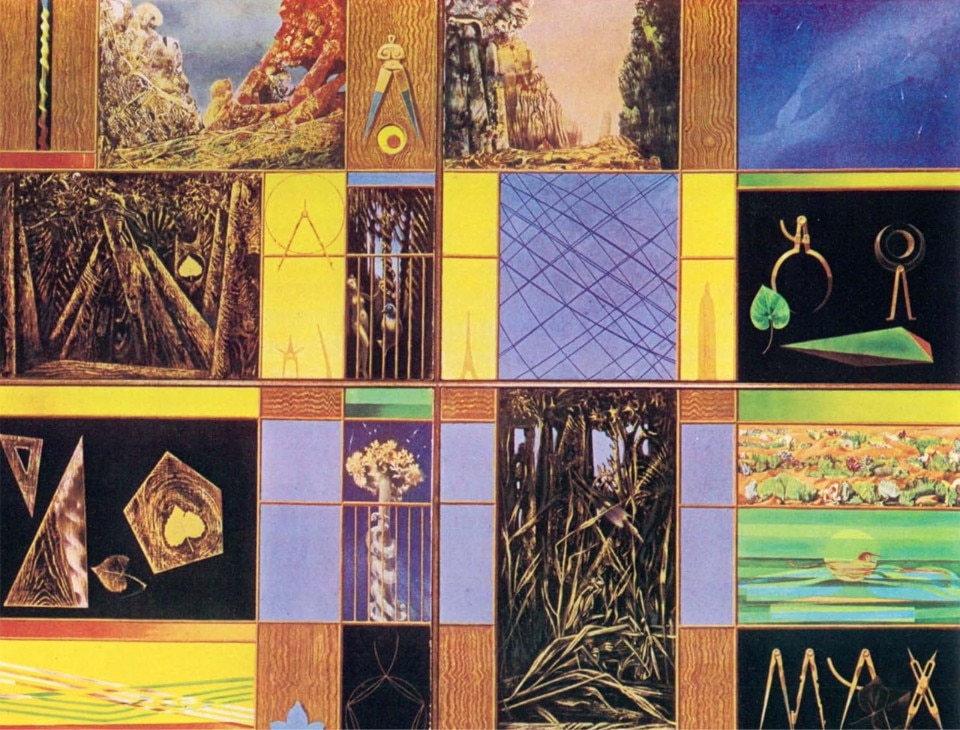

Max Ernst’s painting charms and fascinates because it is first and foremost intelligent and mental. His work is unblemished by monumentality. There is no mock velvet in this painting. Its sensual tone is occasionally fragile. But the quality of his imagery is outstandingly dignified in its refinement. Max Ernst fully illustrates the romantic component of Surrealism. His painting deals with states of mind. His greatness lies in the fact that he is not restricted to re-transcribing Breton’s moods precisely as laid down by the surrealist Pope in the Manifesto. Max Ernst is too imaginative to do that. He has imagination in the sense implied by a systemic structure of the imaginary: a self-sufficient organisation of fantasy as a language system.

The recurrent semeiotic bird takes on the value of an operational symbol, just like that of the sun-moons, in the firmaments of the “parquets frottés” The canvas dated 1942 and entitled “Surrealism and painting”, the brand image of Breton’s postwar militantism, will have a place in all anthologies of art history; and it is significant to see in it (contamination by Matta) the cancerous growth of the bird that turns into a monster. Max Ernst’s painting never asserts itself through its strictly pictorial qualities but, I repeat through the quality of his imagination, which is the figurative equivalent to Paul Klee’s abstract fantasy. In both painters one finds this fragile, fantastic will-o’-the-wisp poetry. The humus of this imagination gets its food from the same sources, and on the same scale as Germanic humanism.

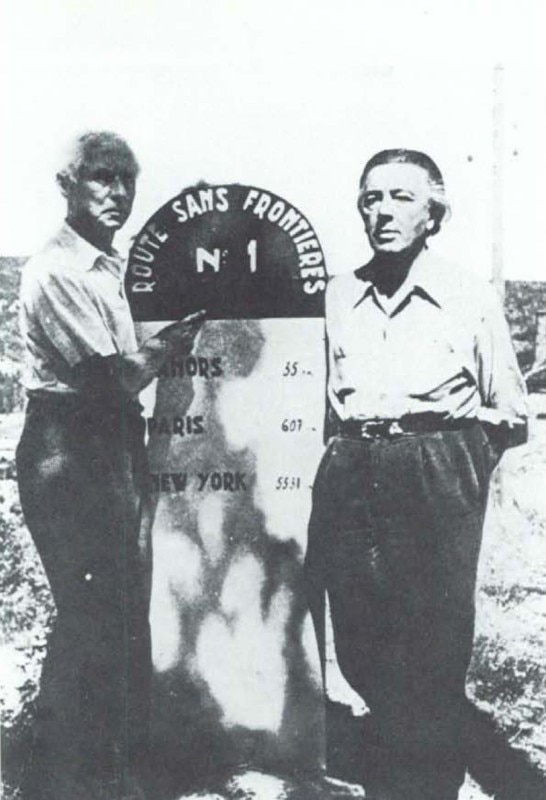

It has taken Max Ernst almost 85 years of internationalist existence to offer the Paris public of 1975 the most authentic face of German humanism: a fantasy as generous as it is fragile. Max Ernst, a man of successive and different passports, a traveller without frontiers, has kept the underlying flavour of his Rhineland soil in his luggage. He is the most fundamentally German painter of the 20th century.

Pierre Restany