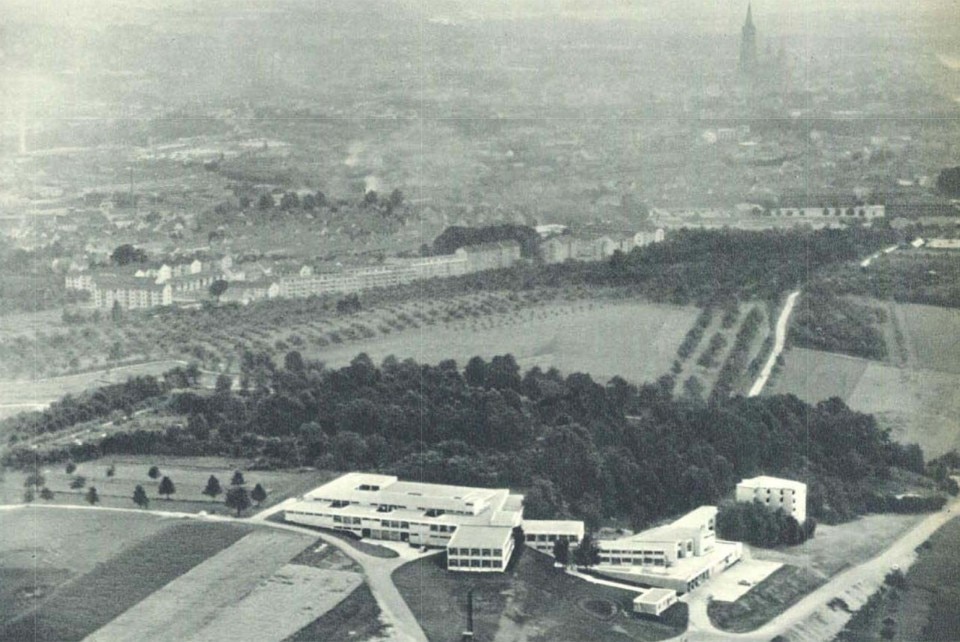

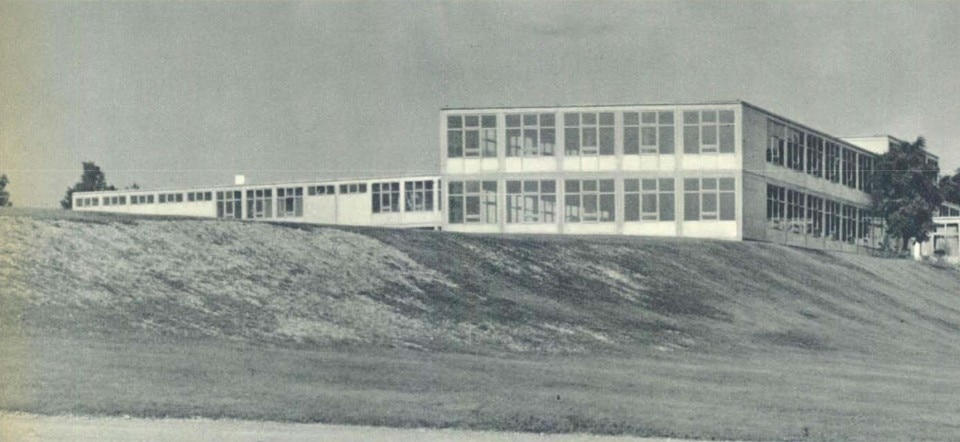

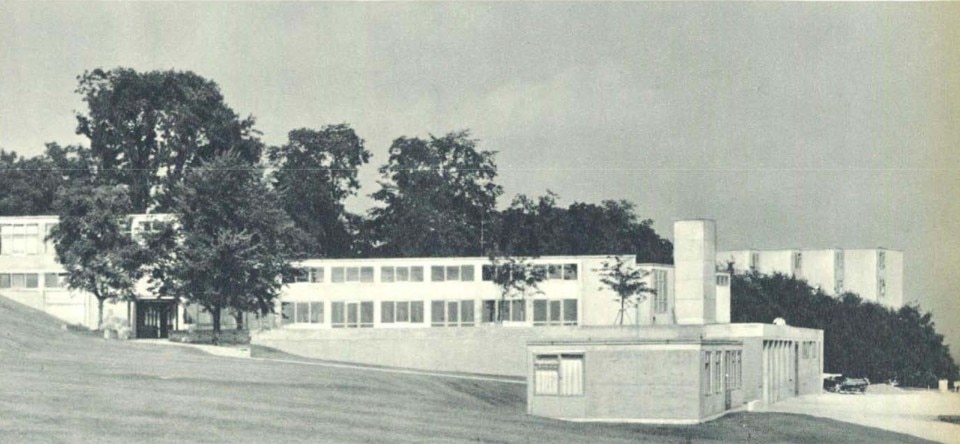

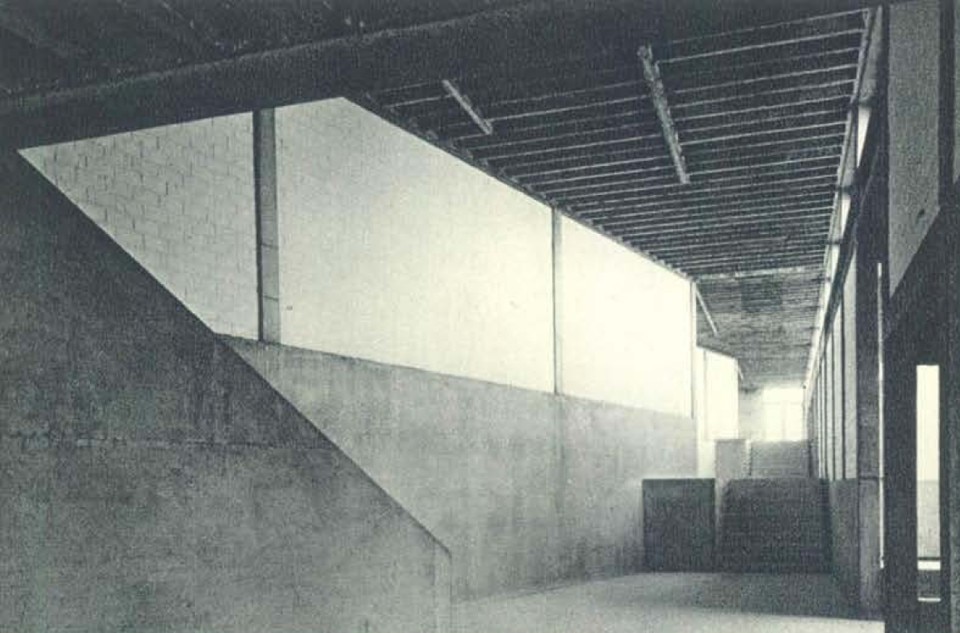

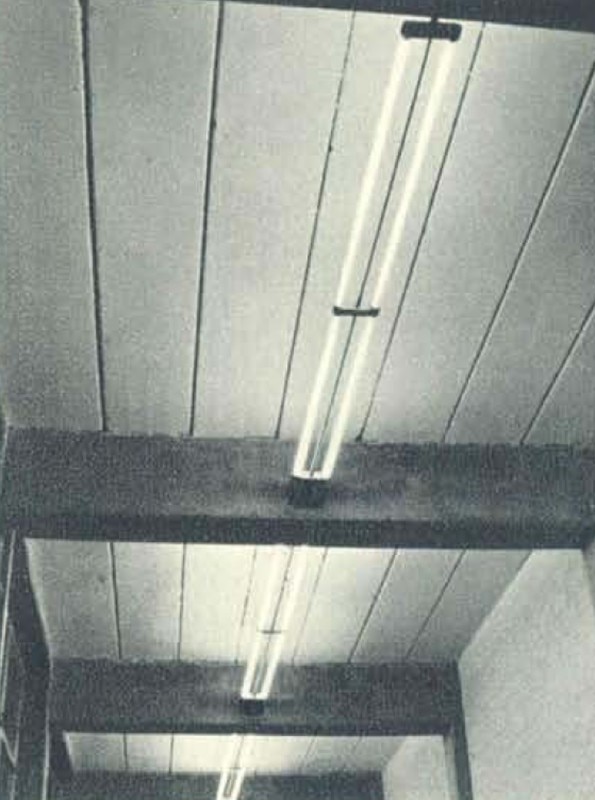

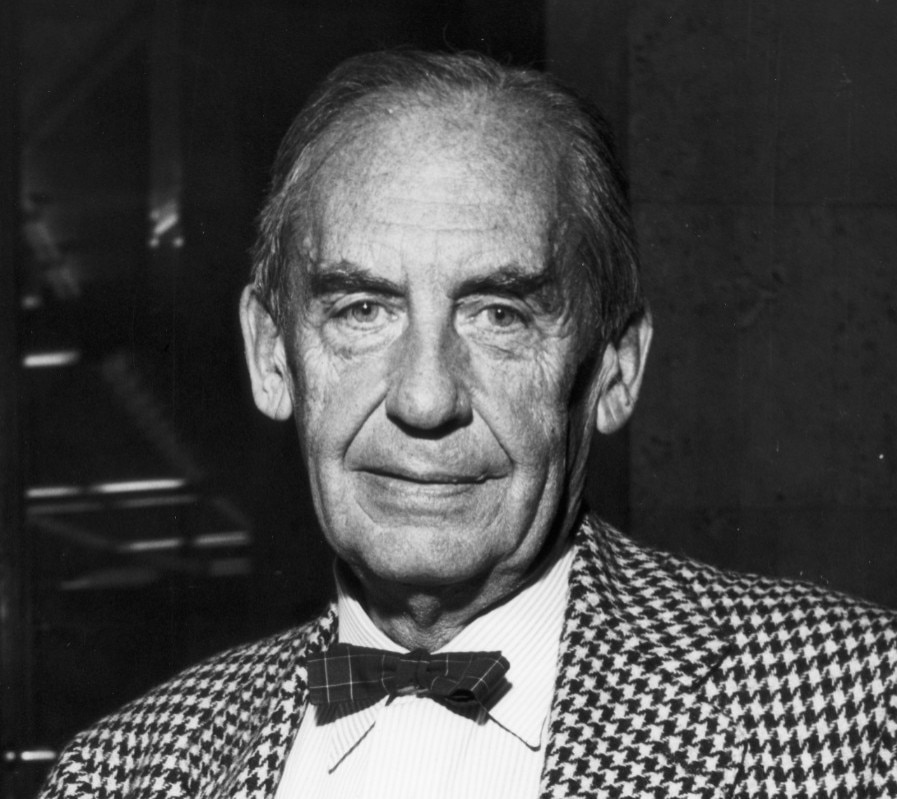

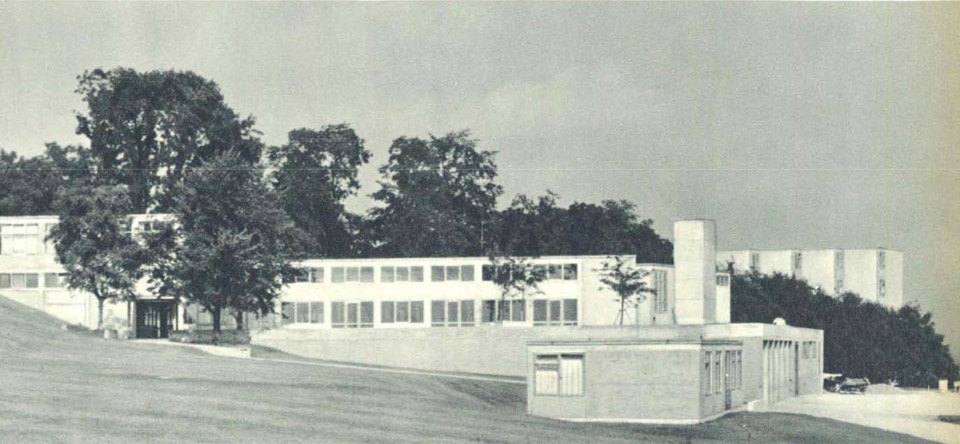

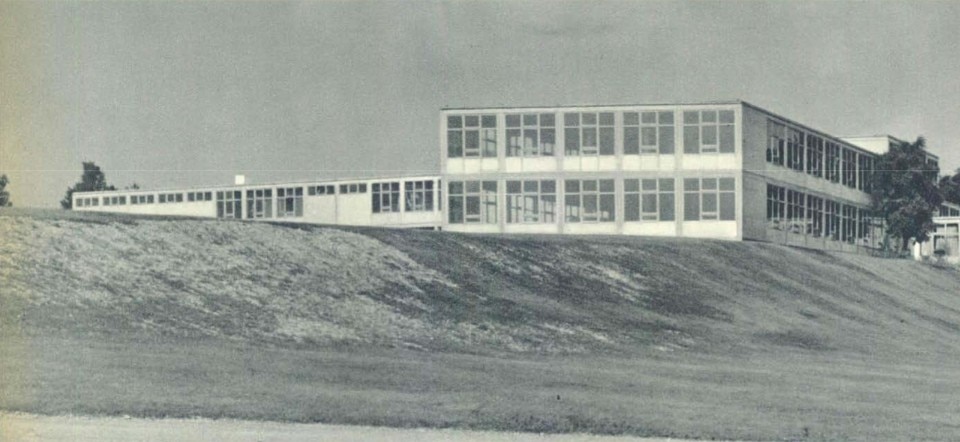

The Hochschule für Gestaltung was officially opened in Ulm, Germany. on 2 October 1955. Founded and directed by Max Bill, it is the ‘university for form’, the school-workshop with which Bill is courageously reviving the concepts and work of Gropius' Bauhaus.

We reproduce this previously unpublished speech delivered by Gropius on that occasion because it represents a memorable document of his thought and belief.

Almost 30 years have passed since the day when I was in a situation like the one that Professor Max Bill is facing today- the opening in 1926 of the building that I designed for the Bauhaus in Dessau.

But my participation at today's celebration has an even deeper significance, because we can say that the work that began at the Bauhaus and the principles conceived then have found their new German motherland here in Ulm, as well as the possibility of their further organic development. If this institution remains faithful to its ideal calling, and if politics are more stable than at the time of the Bauhaus, our ‘university for form' will be able to expand its influence beyond the borders of Germany, and convince the world of the need for and the importance of the work of artists for the prosperity of a genuine progressive democracy. I see its great educational calling in this possibility.

In our age, which is dominated by science, artists have been all but forgotten. Further, they are often derided and unjustly judged to be an unnecessary luxury in society. What civil nation today supports art as an integral, essential element of the life of its people? Today, on account of its own history, Germany has the great cultural opportunity to restore importance to the magical element as opposed to the logical one of our time, in other words, to restore the legitimacy of artists by reintegrating them into our modern production process.

The hypertrophy of the sciences has suffocated the magic in our lives. In this extraordinary flourishing of logic, the poet and the prophet have become the unloved children of an overly practical society. There is a saying by Einstein that illuminates our condition: “Perfect instruments and confused goals characterize our time”.

The spiritual climate that predominated at the end of the century still preserved a static and contained character sustained by an apparently unshakeable faith in 'eternal values: This faith was supplanted by the concept of a universal relativity, of a world in uninterrupted metamorphosis.

And the consequently profound changes for human life have all, or nearly all, come to pass in the industrial development of the last half-century, and they have been more profound during this brief period than in all centuries taken together. The head-spinning rapidity of change has made many people unhappily anxious, pushing many to the edge of a nervous breakdown. The natural laziness of the human heart cannot withstand this rhythm. Thus, we must fortify ourselves against the inevitable tremors, as long as the avalanche of scientific and philosophical ideas drags us along with such fury. Clearly, what we most urgently need in order to shore up our unsteady world is a new

orientation in the field of culture. Ideas are omnipotent. The spiritual direction of human evolution has always been determined by the thinker and the artist, whose creations are beyond logical ends. We must return to them confidently, otherwise their influence will not be effective. Only when people spontaneously accepted the seed of a new civilization was it able to set down roots and spread. The unified, coherent attitudes of the society that corresponds to the truest nature of human life, and which is indispensable for its progress, could be formed only where new creative forces could penetrate every aspect of human life.

Until a few generations ago, our social world had a balanced unity, in which everyone had his place, and firmly rooted habits had their natural value. Art and architecture developed organically through a slow process of growth, and were accepted aspects of civilized life. Society was still a whole. But then, at the beginning of the machine age, the old social form disintegrated. The very instruments of civil progress ended up dominating us. Instead of trusting in moral principles, modern man is developing a Gallup poll mentality that is mechanically based on quantity rather than on quality and is aimed at immediate utility more than the good of the spirit. Even those people who opposed this standardization of life, this impoverishment of the spirit, were often misunderstood and even suspected of desiring exactly what they had decided to fight against. Perhaps I could cite the example of what happened to our university, and my own experiences. Not only during the Bauhaus but throughout my life, I have had to defend myself personally against the reproach of ‘unilateral rationalism’. Shouldn't the decision of my collaborators at the Bauhaus have sufficed, with their intuitive artistic talents, to shield me from this criticism? Not at all, and even Le Corbusier was exposed to that same unjust suspicion, because he preached the gospel of the 'machine for living: And can we imagine an architect more blessed with a sense of the magical than he? The pioneers of this modern movement were falsely presented as fanatical followers of rigid and mechanical principles, as glorifiers of the machine, at the service of a ‘new objectivity’, and by now indifferent to every human value. Since I, myself, am one of those monsters, I am amazed, after the fact, that people managed to exist on the basis of such a miserable premise.

In reality, of course, our first problem was to humanize the machine and find a new, coherent form of life. This is also the challenge faced by this School, and it, too, will face similar battles.

Aiming to place the new means at the service of human ends, the Bauhaus then attempted to demonstrate in practice what it was preaching: the need for a new balance between practical needs and the aesthetic—psychological needs of the time. I remember the preparations in 1923 for our first exhibition, which was supposed to illustrate the complexity of our concept. I had entitled the exhibition Art and Technique: a New Unity, which certainly did not reflect a mechanistic concept. For us, functionalism was not only identified with the rational approach but also involved psychological problems. We thought that the realization of form had to ‘function’ in a physical and psychological sense. We were perfectly aware that emotional needs are no less powerful and urgent than practical ones. But the idea of functionalism was, and is still, misunderstood by those who see only its mechanical aspect. Naturally, machines and new scientific possibilities were of extreme interest for us, but the accent fell not so much on the machine in itself as on the desire to place it more intensely at the service of life.

If I look back, I have to say that our generation has committed itself too little rather than too much to resolving the problems of the machine, and that the new generation must tame it in order to arrive at form, if it wants the spirit to reclaim its predominance.

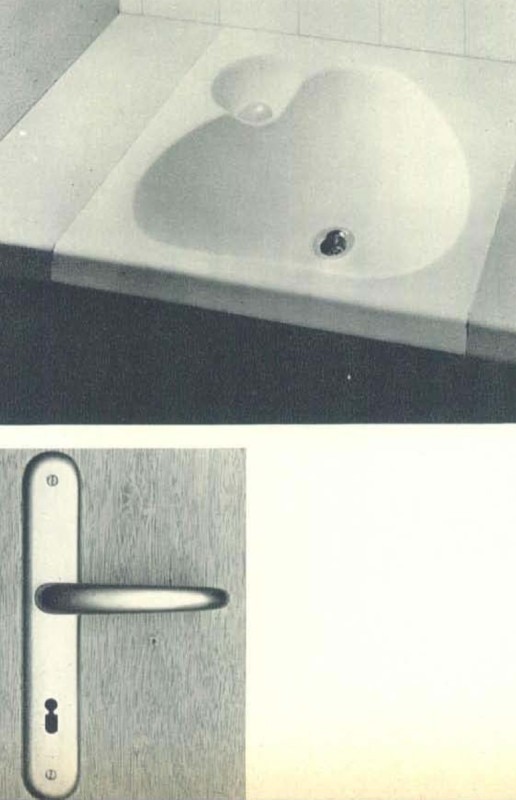

All problems of beauty and form are problems of psychological function. In a unified civilization, they are present in all aspects of the production process, from the design of a practical object to that of a large building. It is the engineer's task to realize a technically functional structure; the architect, the artist, will seek expression. He will use structure, but it is only beyond technique and logic that the magical and metaphysical aspect of his art will be revealed, when he possesses the gift of poetry.

A gift, an inborn talent can be brought to light by what we will call creative education. Education means very little if it means only the accumulation of notions.

The essential objectives of education must be characterized by the clarity and power of convictions and ideas, the spontaneous desire to serve everything: the common cause and education of the senses, not only of the intellect. Professional technical and scientific training must be subordinated

to ethical training. A new system for getting rid of natural presumption, whose perils confront all of us, is by working in a group, the team, in which the individual members learn to subordinate their

own interest to the cause. In this way, the person who will one day be an architect, a designer, will be prepared to work alongside an engineer, a businessman and a technician, with equal rights and responsibilities in the world of production. It is truly necessary for the architect to participate in this form of group work: He sits immobile on his old pile of bricks and runs the risk of losing any chance of succeeding in the world of industrial production.

If we analyse the contemporary world of production, we find the same conflicts as in the struggle of the individual against the spirit of the masses. In contrast with the scientific process of mechanical reproduction (today we speak of ‘automation’), the artist's quest is for frank and free forms that interpret the vital sense of daily life. The work of the artist is fundamental for a genuine democracy and unification of ends, since the artist is the prototype of the universal man. His intuitive gifts will save us from the peril of super—mechanization that would impoverish life and reduce men to the condition of robots if it were an end unto itself. A proper education can lead to future, proper cooperation among the artist, the scientist and the businessman. Only by working together can they develop a standard of production whose measure is man, in other words, one that gives equal importance to the imponderables of our existence and to physical needs. I believe in the growing importance of group work for the spiritualization of living standards in democracy. Certainly, the spark of the idea that first gives life to a work appears in the ingenious individual, but in close cooperation with others, in a team, in the mutual exchange of ideas. And it is in the exciting crucible of criticism that we achieve the greatest results. Working together towards a lofty goal stimulates and heightens the abilities of all participants.

I would like to wish Max Bill, Inge Scholl, the Faculty, and the students the ability to generate within themselves the creative forces necessary for this idea of unity and to form a group capable of meeting all challenges and preserving their lofty goal in the heat of the inevitable battles that they will face. In other words, I hope that they do not pursue a style but constantly seek new expressions and new truths.

I know how difficult it is to pursue this approach when the formal product of conservative habit and technique is continuously presented as the will of the people. Each experiment demands absolute freedom as well as the support of authorities and private citizens with a broad vision, who look with benevolence on the often poorly understood labour pains that accompany the birth of something new. Give time to this ‘university for form’ so that it can develop in peace. An organic art demands continuous renewal. History shows that the concept of beauty has continuously changed with the development of the spirit and technique. Whenever man thought that he had discovered eternal beauty, he fell into the trap of imitation and sterility. True tradition is the product of uninterrupted development. For its quality to serve as an inexhaustible stimulus for men, it must be dynamic and not static. There is nothing final in art, but only continuous metamorphosis, in parallel with the change of technical and social reality.

During the long trip that I took last year to Japan, India and Thailand, I came into contact with the mentality of the Orient, a mentality that is so different — so secret and magical — from the logically practical mentality of Western man. Will the future lead us through greater freedom of relationships in the world to a gradual interpenetration of these two attitudes of the spirit — the balance between the element of dream and soul, and the element of logic and intellect? Thanks to the fullness of the artist's nature, he is predestined to further this interpenetration, starting with its realization in himself — and this is a goal worthy of our enthusiasm.

(This English translation by Bradley Baker Dick was published in Charlotte and Peter Fiell (eds.), Domus IV 1955-1959, Köln, Taschen, 2006, p. 559-60.

A special acknowledgment goes to HfG Archiv Head of Department, Dr. Martin Maentele, for the documental contribution)