By the end of the 1970s, Ricardo Bofill's language had already crossed different levels of architectural espressione quite easily labeled as dramatic, among the first monolithic terrace fronts on carrer Bach in Barcelona, the architect's own post-industrial residence La Fábrica, or the polychrome sculptures of Walden 7, Xanadú, and the iconic Muralla Roja. The following decade chronicled the approach to a more unapologetically monumental and historicist language of mirrored glass and gables, pediments, colonnades, mainly in prefabricated concrete: in a word, postmodern.

By the intersections of history, this linguistic turn (actually an evolution) would meet the new socialist France of Francois Mitterrand, all Grands Travaux and massive plans for social housing: wouls such monumental expressions become monuments of a socialist state? This was the first of many questions that historian Fulvio Irace addressed in January 1986, on the issue 668 of Domus.

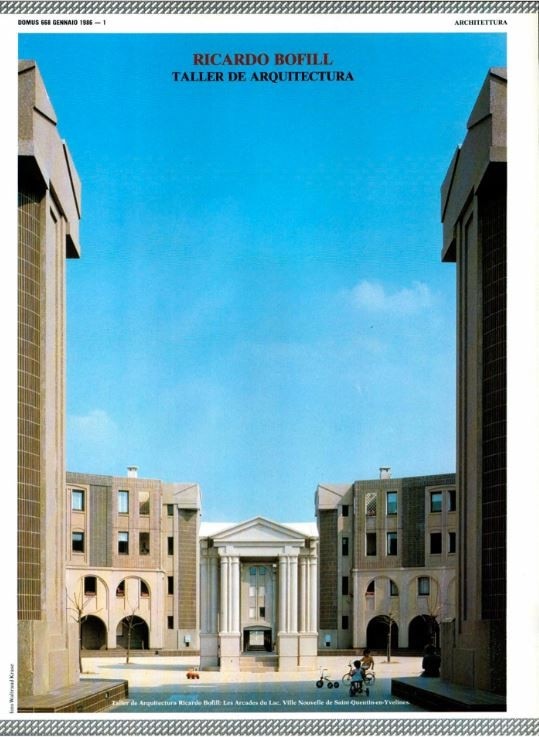

Ricardo Bofill, Taller de arquitectura

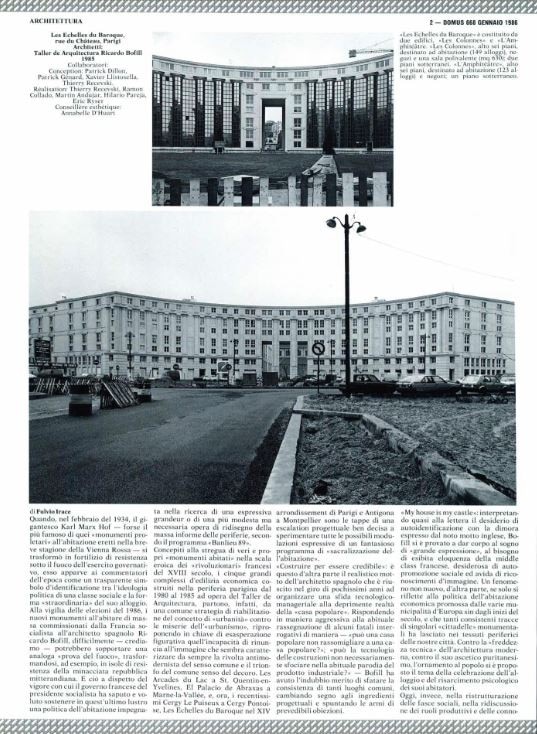

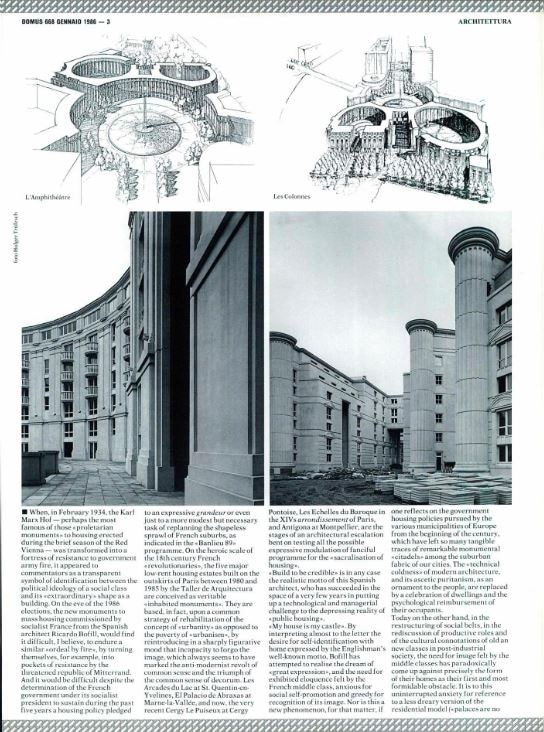

When, in February 1934, the Karl Marx Hof – perhaps the most famous of those “proletarian monuments” to housing erected during the brief season of the Red Vienna – was transformed into a fortress of resistance to government army fire, it appeared to commentators as a transparent symbol of identification between the political ideology of a social class and its “extraordinary” shape as a building. On the eve of the 1986 elections, the new monuments to mass housing commissioned by socialist France from the Spanish architect Ricardo Bofill, would find it difficult, I believe, to endure a similar “ordeal by fire”, by turning themselves, for example, into pockets of resistance by the threatened republic of Mitterrand. And it would be difficult despite the determination of the French government under its socialist president to sustain during the past five years a housing policy pledged to an expressive grandeur or even just to a more modest but necessary task of replanning the shapeless sprawl of French suburbs, as indicated in the “Banlieu 89” programme.

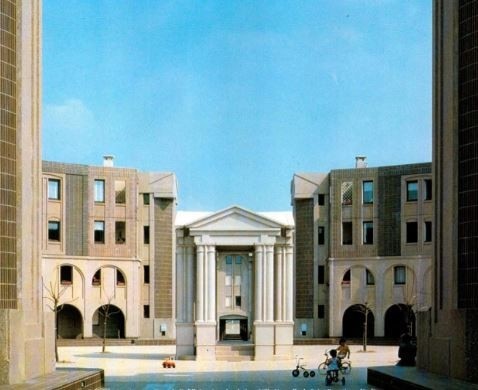

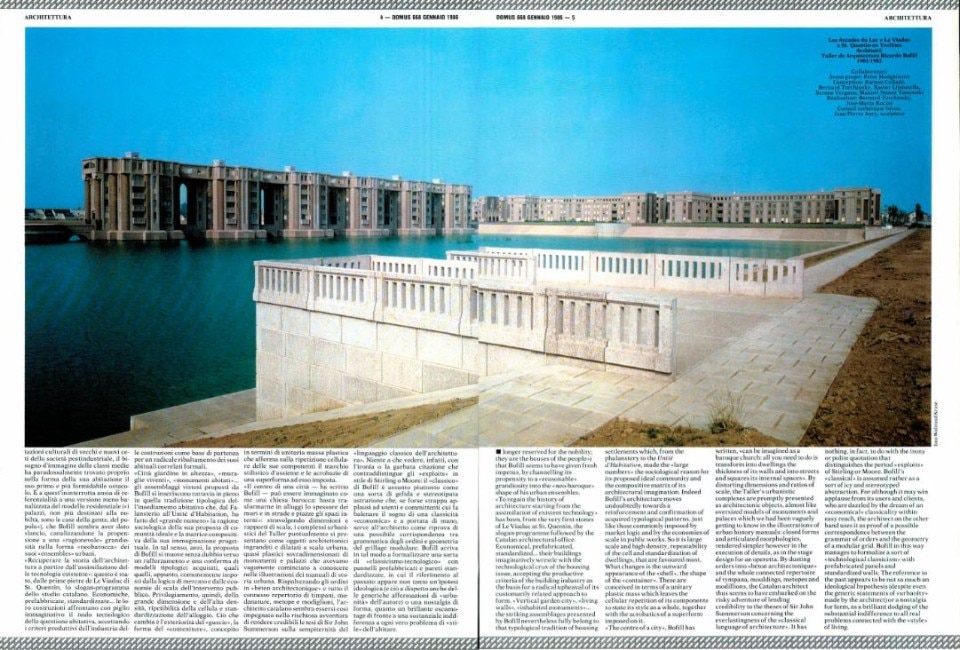

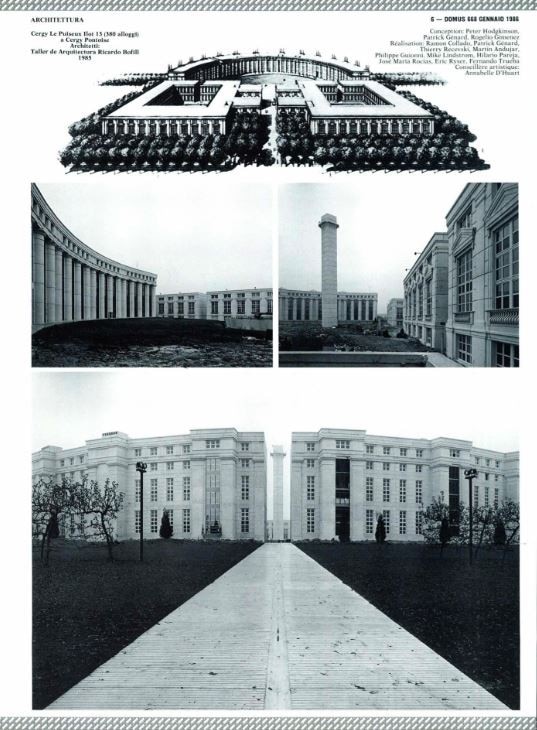

On the heroic scale of the 18th century French “revolutionaries”, the five major low-rent housing estates built on the outskirts of Paris between 1980 and 1985 by the Taller de Arquitectura are conceived as veritable “inhabited monuments”. They are based, in fact, upon a common strategy of rehabilitation of the concept of “urbanity” as opposed to the poverty of “urbanism”, by reintroducing in a sharply figurative mood that incapacity to forgo the image, which always seems to have marked the anti-modernist revolt of common sense and the triumph of the common sense of decorum. Les Arcades du Lac at St. Quentin-en-Yvelines, El Palacio de Abraxas at Marnela-Vallèe, and now, the very recent Cergy Le Puiseux at Cergy Pontoise, Les Echelles du Baroque in the XIVs arrondissement of Paris, and Antigona at Montpellier, are the stages of an architectural escalation bent on testing all the possible expressive modulation of fanciful programme for the “sacralisation of housing”.

“Build to be credible” is in any case the realistic motto of this Spanish architect, who has succeeded in the space of a very few years in putting up a technological and managerial challenge to the depressing reality of “public housing”.

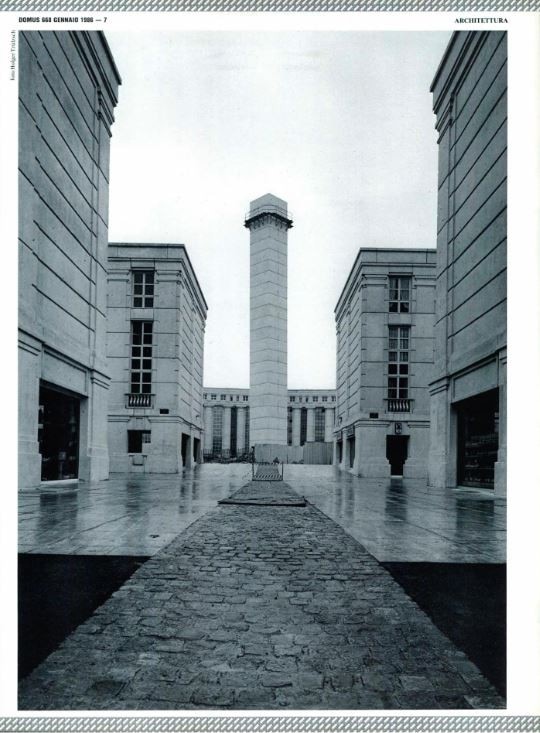

“My house is my castle”. By interpreting almost to the letter the desire for self-identification with home expressed by the Englishman’s well-known motto, Bofill has attempted to realise the dream of “great expression”, and the need for exhibited eloquence felt by the French middle class, anxious for social self-promotion and greedy for recognition of its image. Nor is this a new phenomenon, for that matter, if one reflects on the government housing policies pursued by the various municipalities of Europe from the beginning of the century, which have left so many tangible traces of remarkable monumental “citadels” among the suburban fabric of our cities.

The “technical coldness” of modern architecture, and its ascetic puritanism, as an ornament to the people, are replaced by a celebration of dwellings and the psychological reimbursement of their occupants. Today on the other hand, in the restructuring of social belts, in the rediscussion of productive roles and of the cultural connotations of old an new classes in post-industrial society, the need for image felt by the middle classes has paradoxically come up against precisely the form of their homes as their first and most formidable obstacle. It is to this uninterrupted anxiety for reference to a less dreary version of the residential model (“palaces are no longer reserved for the nobility; they are the houses of the people”) that Bofill seems to have given fresh impetus, by channelling its propensity to a “reasonable” grandiosity into the “neo-baroque” shape of his urban ensembles.

“To regain the history of architecture starting from the assimilation of existent technology” has been, from the very first stones of Le Viaduc at St. Quentin, the slogan-programme followed by the Catalan architectural office. Economical, prefabricated, standardized... their buildings imaginatively wrestle with the technological crux of the housing issue, accepting the productive criteria of the building industry as the basis for a radical upheaval of its customarily related approach to form. “Vertical garden city”, “living walls”, “inhabited monuments”... the striking assemblages presented by Bofill nevertheless fully belong to that typological tradition of housing settlements which, from the phalanstery to the Unité d'Habitation, made the “large numbers” the sociological reason for its proposed ideal community and the compositive matrix of its architectural imagination.

Indeed Bofill’s architecture moves undoubtedly towards a reinforcement and confirmation of acquired typological patterns, just like those commonly imposed by market logic and by the economies of scale in public works. So it is large scale and high density, repeatability of the cell and standardization of dwellings, that are favoured most. What changes is the outward appearance of the “shell”, the shape of the “container”. These are conceived in terms of a unitary plastic mass which leaves the cellular repetition of its components to state its style as a whole, together with the acrobatics of a superform imposed on it.

“The centre of a city”, Bofill has written, “can be imagined as a baroque church: all you need to do is transform into dwellings the thickness of its walls and into streets and squares its internal spaces”. By distorting dimensions and ratios of scale, the Taller’s urbanistic complexes are promptly presented as architectonic objects, almost like oversized models of monuments and palaces which we had been vaguely getting to know in the illustrations of urban history manuals: closed forms and articulated morphologies, rendered simpler however in the execution of details, as in the stage design for an operetta. By dusting orders into “béton architectonique” and the whole connected repertoire of tympana, mouldings, metopes and modillions, the Catalan architect thus seems to have embarked on the risky adventure of lending credibility to the theses of Sir John Summerson concerning the everlastingness of the “classical language of architecture”.

It has nothing, in fact, to do with the irony or polite quotation that distinguishes the period “exploits” of Stirling or Moore. Bofill’s “classical” is assumed rather as a sort of icy and stereotyped abstraction. For although it may win applause from its users and clients, who are dazzled by the dream of an “economical” classicality within easy reach, the architect on the other hand uses it as proof of a possible correspondence between the grammar of orders and the geometry of a modular grid. Bofill in this way manages to formalize a sort of “technological classicism” with prefabricated panels and standardized walls. The reference to the past appears to be not so much an ideological hypothesis (despite even the generic statements of “urbanity” made by the architect) or a nostalgia for form, as a brilliant dodging of the substantial indifference to all real problems connected with the “style” of living.