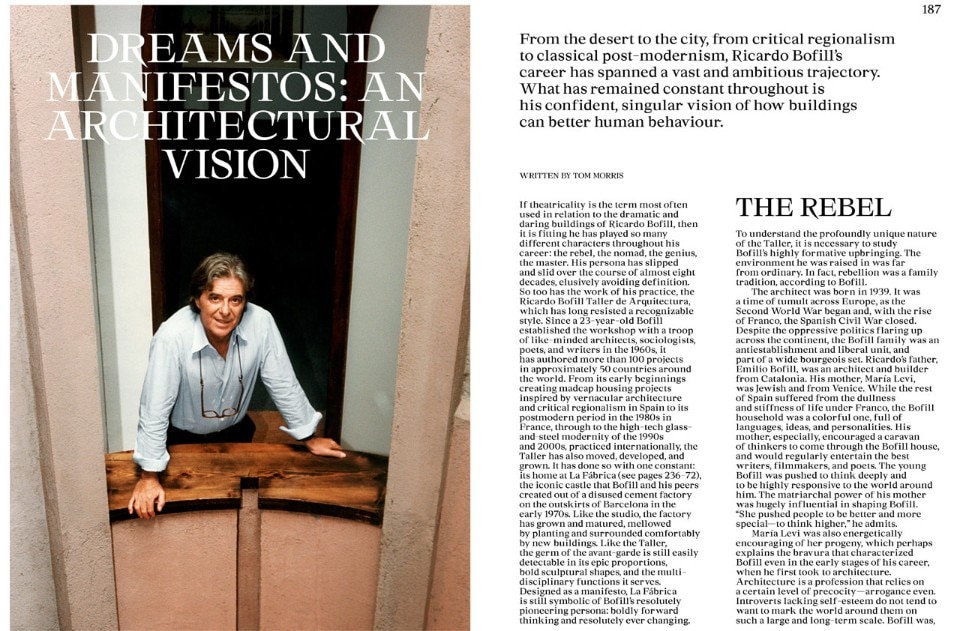

Who was Ricardo Bofill?

We are not going to question the plain impossibility to define individual identity; still, should we as Domus, we would be answered with the portrait of a not-so-discreet figure, someone not easily accepting to fit the categorizations of history of contemporary architecture.

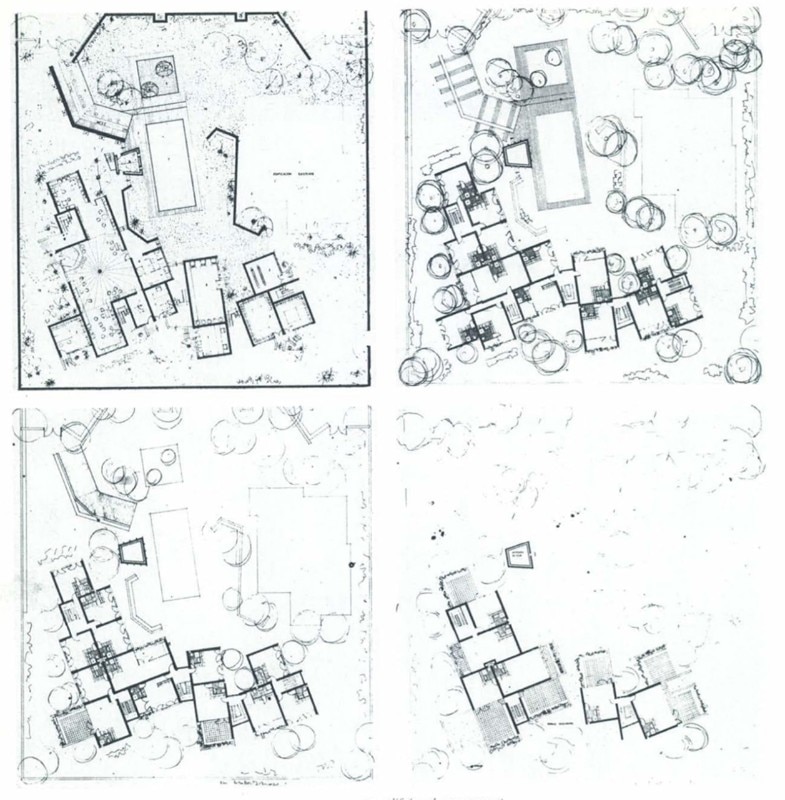

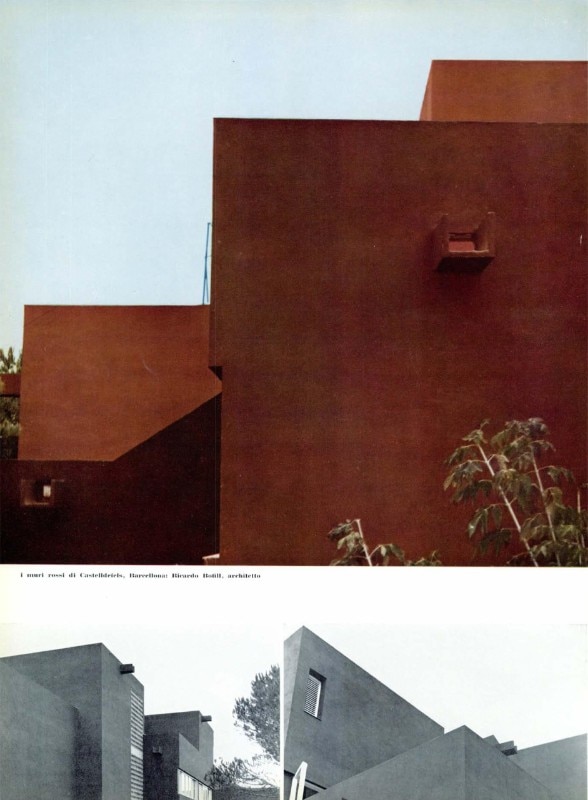

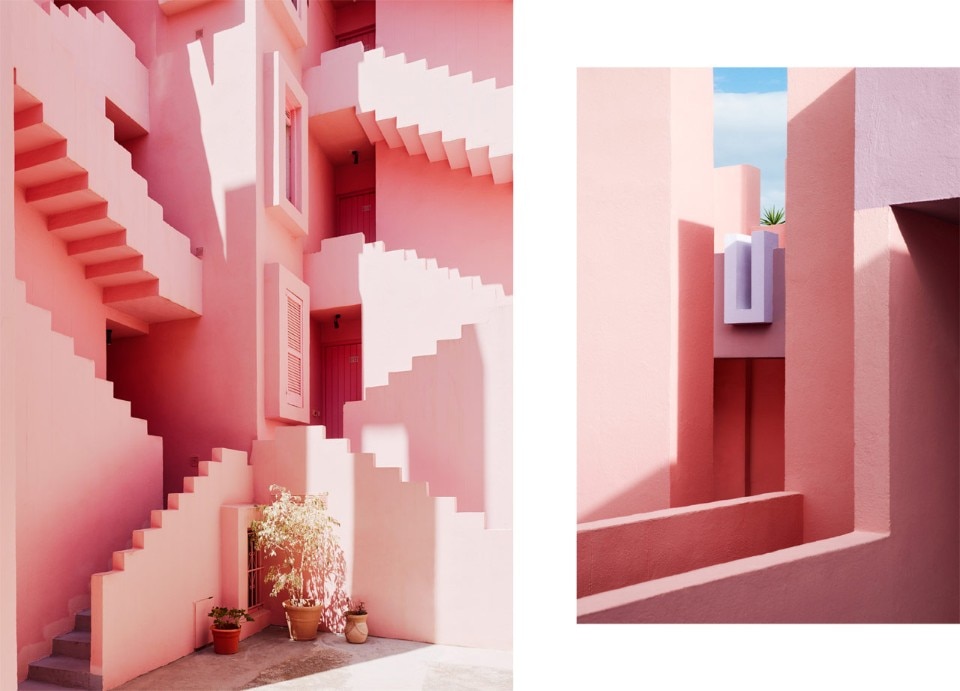

A strongly critical — and criticized — architect, since the beginning of his career Bofill finds his space on Domus, when ithe late-francoist 60s, he would contest and at the same time exploit the immobility and isolation of such context to stand out as a disruptive intellectual figure. And his House with Red walls (not the Muralla Roja in Alicante), published by Domus in 1965, comes as a demonstration, with the colour palette of his exterior overtly questioning the cliché of Mediterranean white. (I muri rossi di Castelldefells, Barcellona, in Domus 429, August 1965).

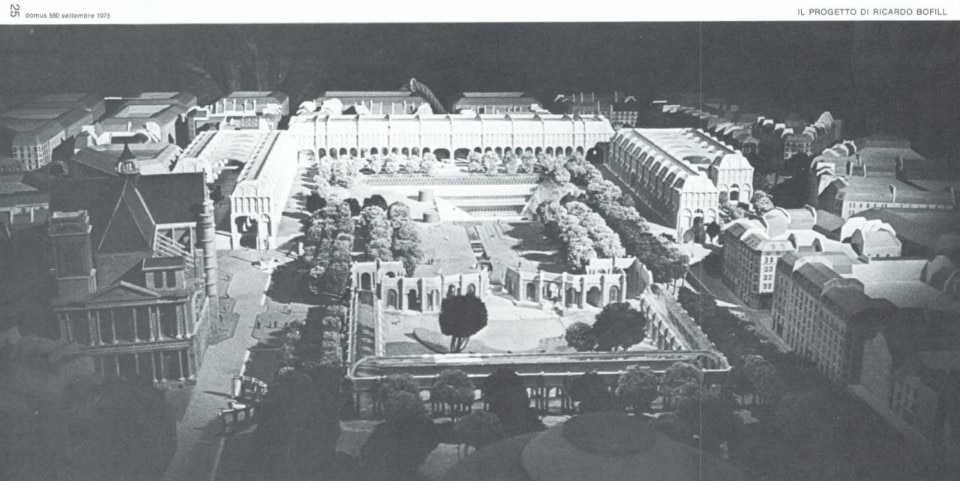

Considered by some a reactionary Franco-Fascist, and by others a radical Communist, for Bofill, poetry, ruins, green grass and a sense of meaningful space were supposed to fill up the void of Les Halles (Ionel Schein, 1975)

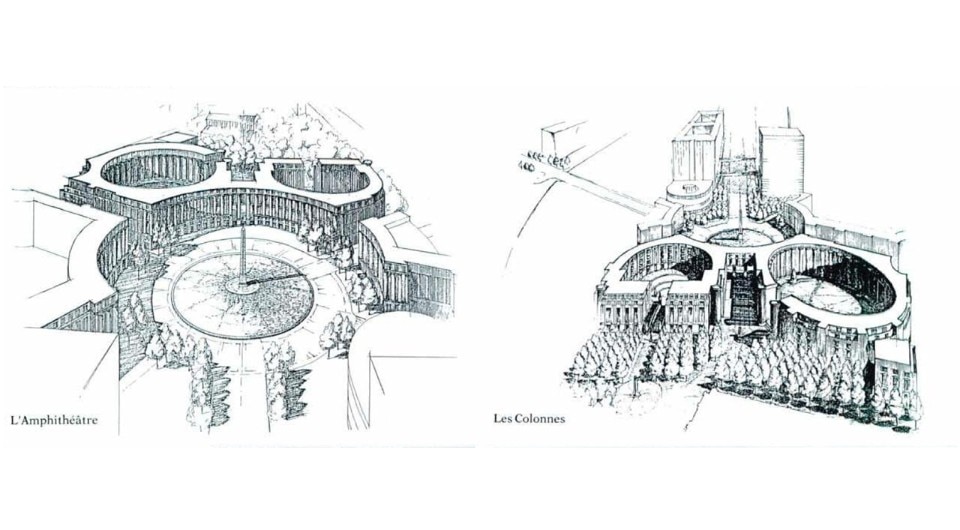

We would find Bofill some ten years later, in the flaming compte-rendus by Ionel Schein on the complex redesign of the Halles in Paris. (L’impostura, in Domus 550, September 1975, the source of our opening quote. La descente aux enfers, in Domus 601, December 1979). Bofill had already entered a second and long-lasting professional phase, where he developed his signature connection to history and historicism; Schein outlined a portrait of a character taking part to a roleplay of deception on the Halles, a figure that got partially sidetracked because of intellectual vocation tackling a scenario that was in the end owned by big capital and the mneed to fulfil its requirements as much as possible (Bofill had by the way been invited by president Giscard d’Estaing to conceive a masterplan and the architectural guidelines for intervention).

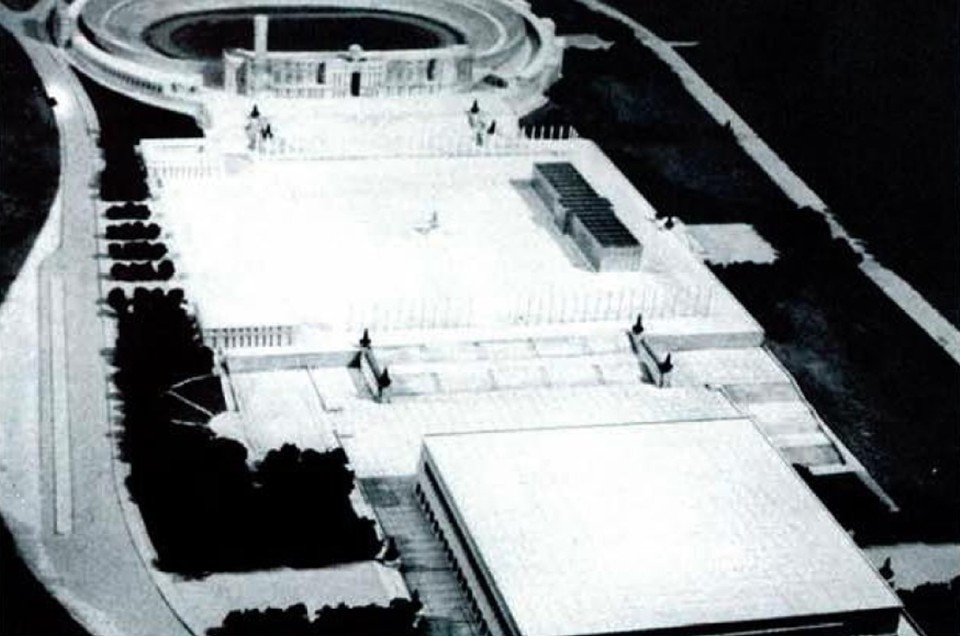

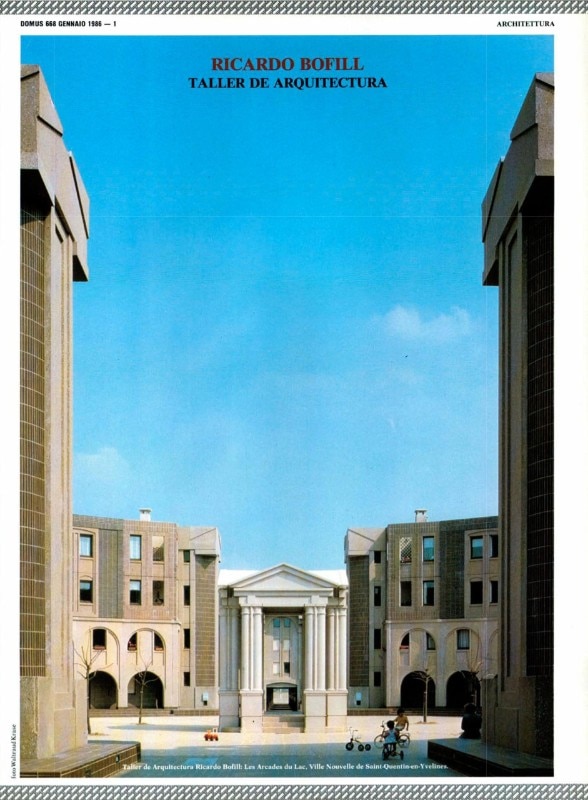

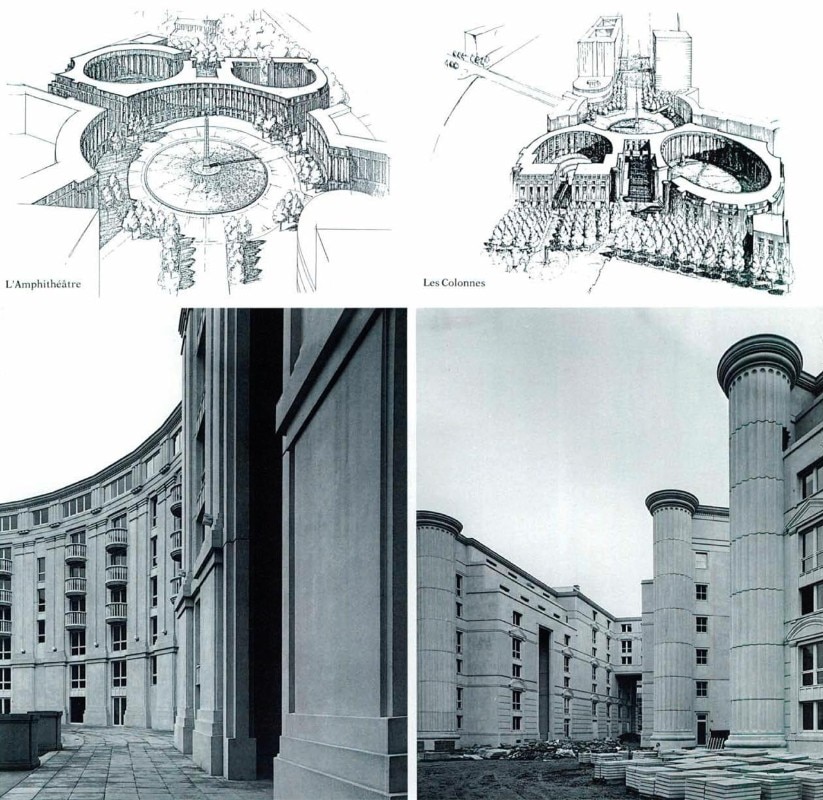

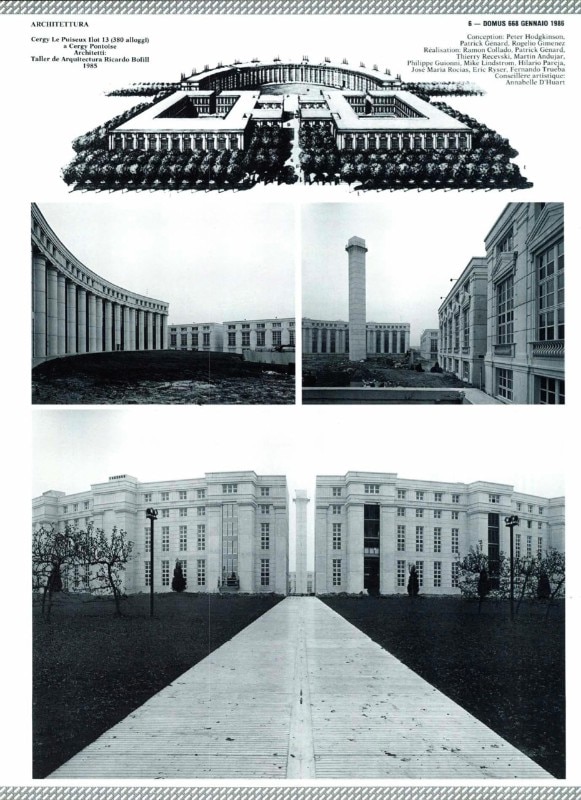

In 1986, Fulvio Irace would finally give an integral outline of Bofill’s trajectory by instroducing his most famous projects of urban ensembles in France: Les Arcades du Lac in St. Quentin-en-Yvelines, the Palacio de Abraxas in Marne-la-Vallée, the Cergy-Pontoise complex, Les Echelles du Baroque in XIVe arrondissement of Paris, the Antigone in Montpellier. Instead of providing a full-size roasting of the Catalan architect, the portrait lets his dimension of peculiarity come to the surface, exploring the cliché of postmodernism he was automatically awarded, as well as those element he confidently dealt with: form, history, large urban scale, a completely new relationship between monumentality and dwelling.

“(…) the need for image felt by the middle classes has paradoxically ome up against precisely the form of their homes as their first and most formidable obstacle. it is to this uninterrupted anxiety for reference to a less dreary version of the residential model (‘palaces are no longer reserved for the nobility; they are houses of the people’) that Bofill seems to have given fresh impetus, by channeling its propensity to a ‘reasonable’ grandiosity into the ‘neo-baroque’ shape of his urban ensembles.

(…)

Bofill’s architecture moves undoubtedly towards reinforcement and confirmation of acquired typological patterns, just like those commonly imposed by market logic and by the economies of scale in public works.

(…)

Bofill in this way manages to formalize a sort of technological classicism with prefabricated panels and standardized walls. The reference to the past appears to be not so much an ideological hypothesis (…) or a ‘nostalgia’ for form, as a brilliant dodging of the substantial indifference to all real problems connected with the ‘style’ of living.”

(Ricardo Bofill – Taller de arquitectura, in Domus 668, January 1986)

The centre of a city can be imagined as a baroque church: just turn the thickness of the walls and the streets and squares and the interior spaces into accommodation. (Ricardo Bofill)

In the following decades, this character of technological classicism would mark the most of Bofill’s realizations like the crescent for the harbor in Savona, announced by Domus in 2006. But most of all, Bofill became a theoretical presence, continuously summoned, even when it came to defining other architects in comparison. In 1991, Pierluigi Nicolin built the teams for architectural championship in the new decade and — in the round of Urban Reconstruction — he placed Bofill in the “tradition” team together with Quinlan Young, in opposition to the “modernity” of Foster and Rogers. ( Le nuove condizioni del progetto d’architettura, in Domus 728, giugno 1991) This continued for long, like when in 2003 Dejan Sudjic evoked Bofill to define Santiago Calatrava:

“Unlike his compatriot Ricardo Bofill, who relied on direct imitations of the past to achieve his impact, Calatrava has a way to be able to present his work as aggressively modernas well as sensationally crowd-pleasing.”

(Reputations—Santiago Calatrava, in Domus 863, October 2003)

The most traditional laws... I illuminate them with all the depth of the history of architecture, I mix the vocabularies and I can also deliberately contradict a system, to twist it. (Ricardo Bofill, 1990)

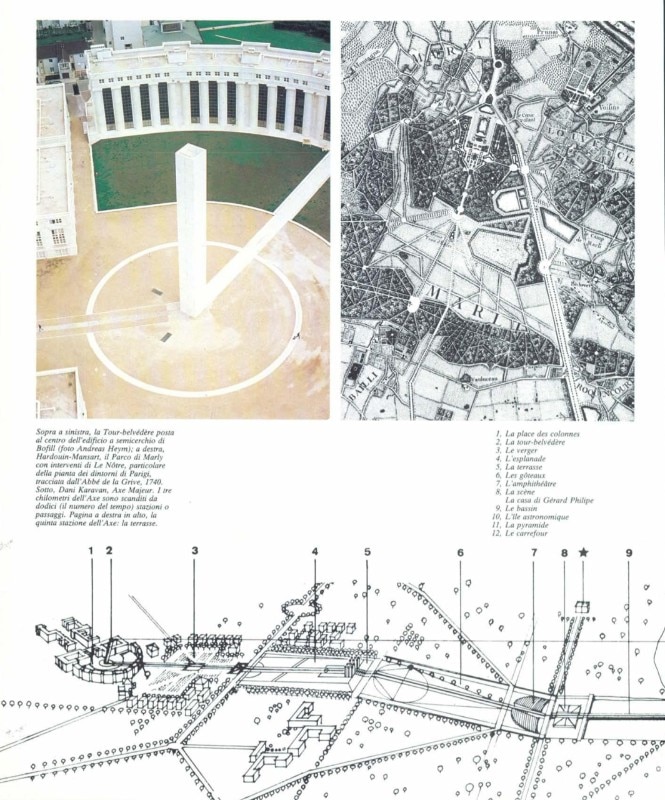

During those decades Bofill had been in fact consolidating his image as a theoretician and a designer, synthesizing his thought through highly symbolical projects such as the integration of Dani Karavan’s Axe Majeur in his Place Ronde in Cergy (L’ “Axe Majeur”, in Domus 716, May 1990) but most of all through books. The reviews published by Domus narrated the words and mode for the critical iconization of the Catalan architect. Gianni Pettena provided a portrait of his “challenge to functionalism” that included his confident relationship with history and politics:

“Bofill thinks every realized architectural work depends from power, be it political or economic. Convinced that the logics of market apply to works of art as well (‘a good architecture is a good deal for everyone’) he states that in order to be real actors in economical completion, architects should first of all define their personality, to consequently produce more appropriate results in dealing with different contexts and social realities.

(…)

Classical architectures offers the possibility to conciliate creation and variation because classicism does not impose a specific type of construction; it just gives the necessary principles to invent new ones. This choice appears in any case as a single step (‘maybe a little longer than others already taken’) in his evolution.

(…)

Bofill justifies the use he makes of such archetypes as the temple and the tower as an attempt to give objects a perspective reference, a place in history, and to give to man a symbolic reference, a spatial perspective.”

(Ricardo Bofill, “Espaces d'une vie” , reviewed by Gianni Pettena on Domus 717, June 1990)

Antonio Pizza would epitomize even more synthetically the two seasons of Bofill’s critique to functionalism, introducing a monography about him in 1994:

“His designs aimed to find out exactly where the boundaries imposed by the local construction conditions were, so he could infringe them … the noticeable impetus sought to overturn architecutre’s basic conditions as a pedantic confirmation of the status quo defined by the regime at that time.

(...)

The unhinibiting experimental drive imploded into a murky sort of ‘updated’ academism.”

(“Ricardo Bofill. Taller de Arcquitectura”, reviewed by Antonio Pizza on Domus 773, July 1995)

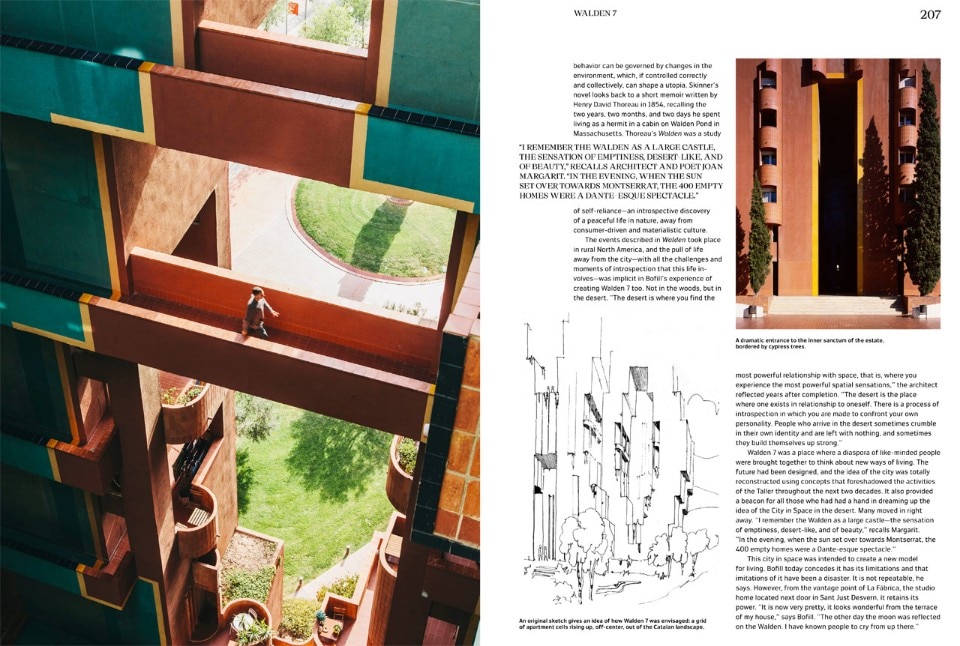

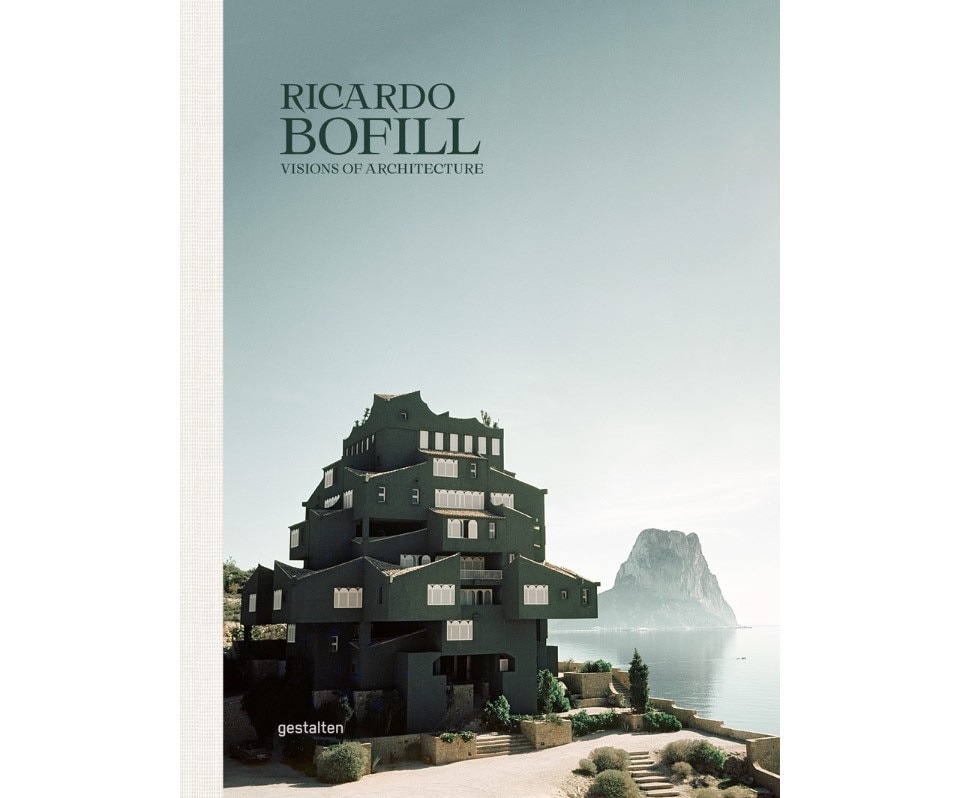

Still, the story of bofill as a presence should not come to its end there. As we are already talking about a presence in theoretical debate as well as in history and the news (March 2005, Domus dedicated his Calendario to the Palacio de Congresos in Madrid that had become the set for an ETA terrorist attack) , we should not ignore how Bofill’s figure has entered a brand new season of critical fortune in the 10s, be it because of the great comeback of Postmodernism and Radicalisms as aesthetics, or because of a new attention towards the properly disruptive principles of his projects of the late 60s. In the photographic book published by Gestalten in 2019, those that are currently considered his fundamental architectures are finally owning the scene: Xanadú and the Muralla Roja in Alicante, Walden 7 in Barcelona; and that architecture that alone would be enough to wipe out all the 70s and 80s clichés on Bofill: La Fabrica, the home to the Talller de Arquitectura. In its loves, Domus has given in 2015 a narrative account of such architecture, exploring the explosive interpretation it gave of an industrial ruin and its meaning but, most of all, exploring the elements that make a habitat out of it: a space structured by a project of experience in shape, light and distribution, in the architectural vision that got all these element together.