On the occasion of the Domusforum 2021 we have questioned ourselves on seven matters to explore the future of the places we inhabit. Two years on from the pandemic that has totally undermined the social assets we took for granted, it is of fundamental importance to reflect on the collective life of tomorrow starting from one of its most important aspects: school.

Digging through the Domus archive we explore how the ideas of yesterday on the theme of new educational models, that look towards inclusivity and to the establishment of a dialogue between school and urban life, can still offer fascinating answers for tomorrow.

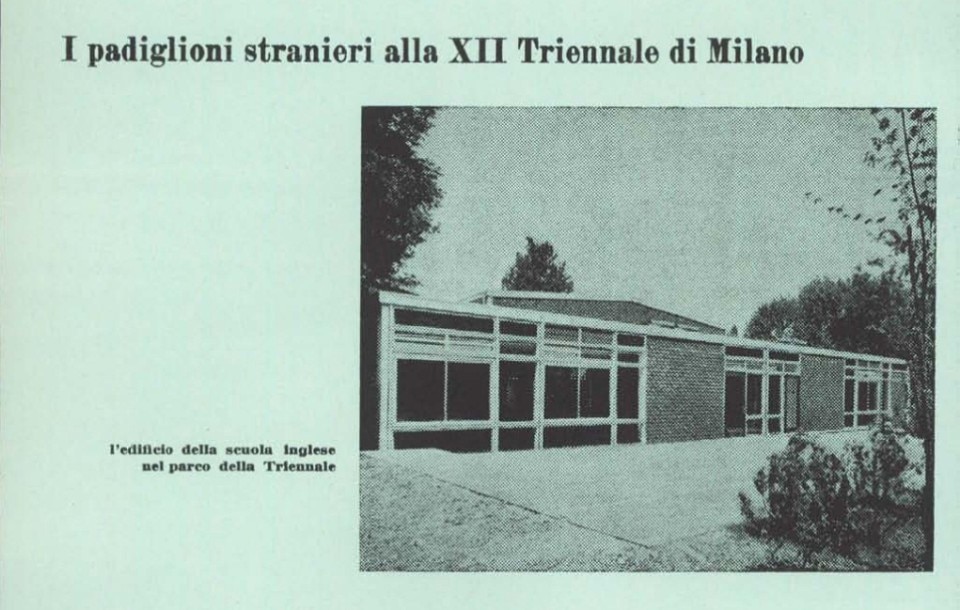

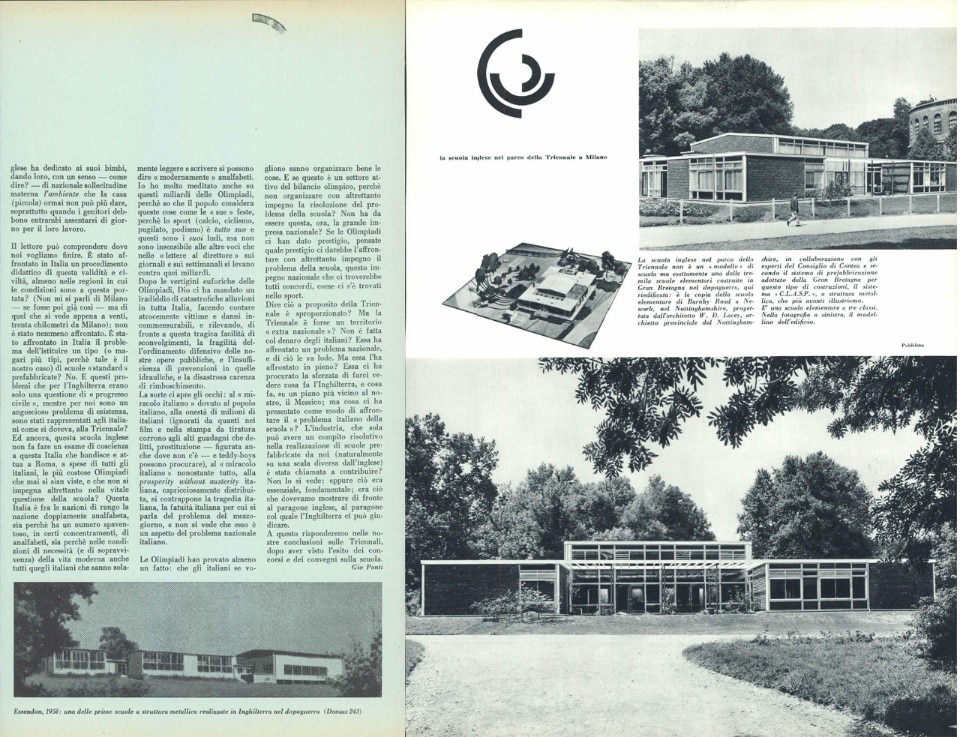

Editor-in-chief Gio Ponti already wrote about this issue in 1960 when reporting from the XXII Milan Triennale on Domus n.372. "Has the issue of building a standardised model of school been faced in Italy yet? No". Ponti's question was moved by the prefabricated schools that England presented at the Triennale, of which they represented "the true gem".

What mostly sparks Ponti's enthusiasm towards these schools is their simplicity to be serially build and reproduced on a low budget – "reproducible prefabricated elements, conceived for a programme of reproduction and distribution [...] across the national territory". In Ponti's view, this project represented a great opportunity to carry out a cultural unification of a country, like Italy, that was still heavily polarised when it came to language and literacy. The construction of schools, hence, played for the national territory the same pivotal role that in those years the Maestro Manzi – a grammar teacher-turned-television personality – had on the Italian public broadcaster RAI.

Italy had just stepped into its post-war economic renaissance, therefore getting accustomed to a whole new standard in matter of public and private architecture. Schools, instead, still represented an outdated and inadequate heredity from the past, both from an academic and architectural perspective. Things, in fact, wouldn't change even in the years to come: just think to the feeling of strict and dusty obsolescence communicated by the cold classrooms where Alain Delon teaches in Valerio Zurlini's Indian Summer, a film that hit the big screen in 1972, over a decade later Ponti's words.

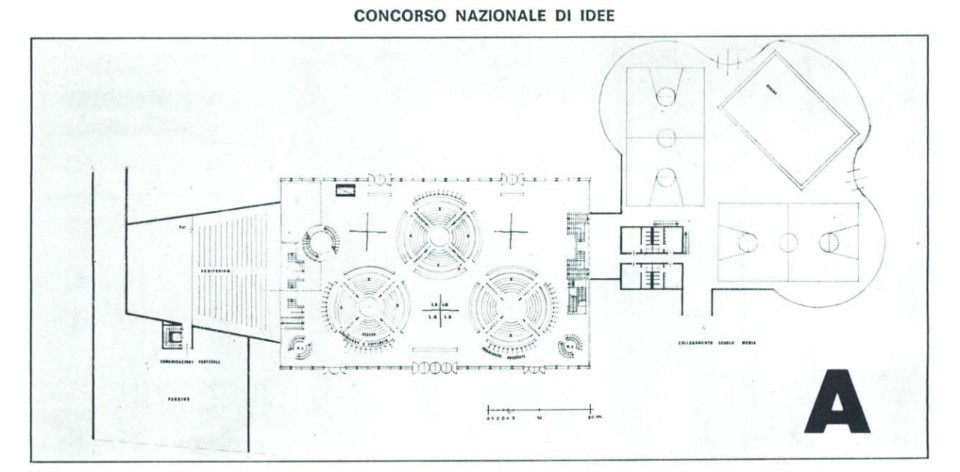

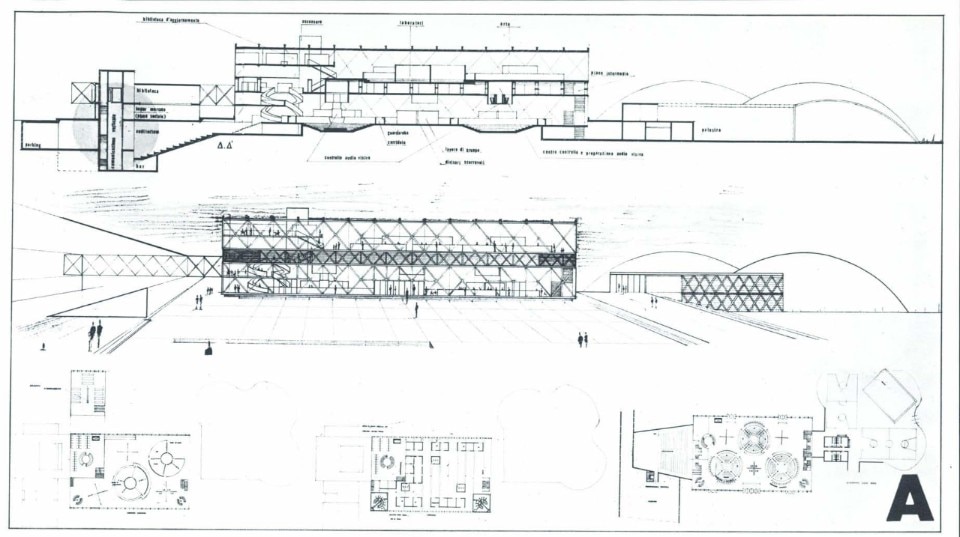

On that very same same year Domus reports about another peculiar project concerning this matter: a school in Milan by the architects Arie Rigler, Mordechai Reibman and Donato D'Urbino.

As we can read in Domus n.513, the project – the winning entry for a competition launched by the Milan province – proposes the concept of a “public and not State school”, that, through structural decisions and its location within the broader urban scenario, succeeds in not reproducing “an unequal, compartmented society”.

In the two-storey building different volumes meet harmoniously and are divided within a "rectangular-shaped primary space for collective use, group study and work; and a secondary space in which the attention is always turned to a 'centre' from which information and communication radiates."

These circular environments present a "sloped" structure thought to host the students and are conceived, with a great degree of farsightedness, to be easily separated or integrated with the rest of the school surface by using "low" and "transparent walls".

"From the center of this area the transmission of information is provided in the traditional ways, or via audiovisual apparatus (which are stored on the upper 'service floor'). All around the sloped steps are spaces for libraries, collective activities, audiovisual devices for individual use, amusement, etc", we can read in the article.

The fascinating Anglo-Saxon and North European approach to learning, where are the multimedia inputs and the collective traits of group work to stand out, however represented the downside of this school, especially in a country whose educational system still relies on the Gentile Reform from 1923.

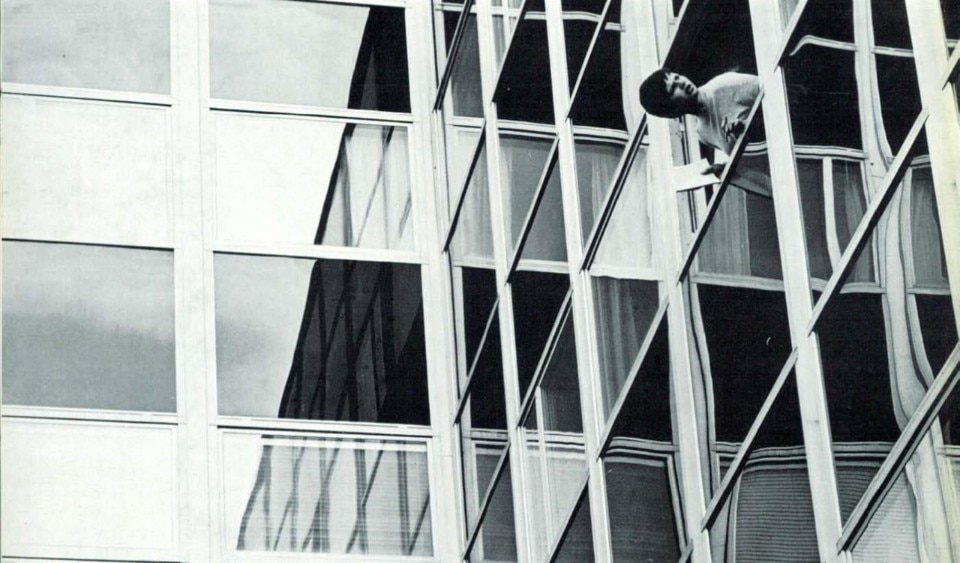

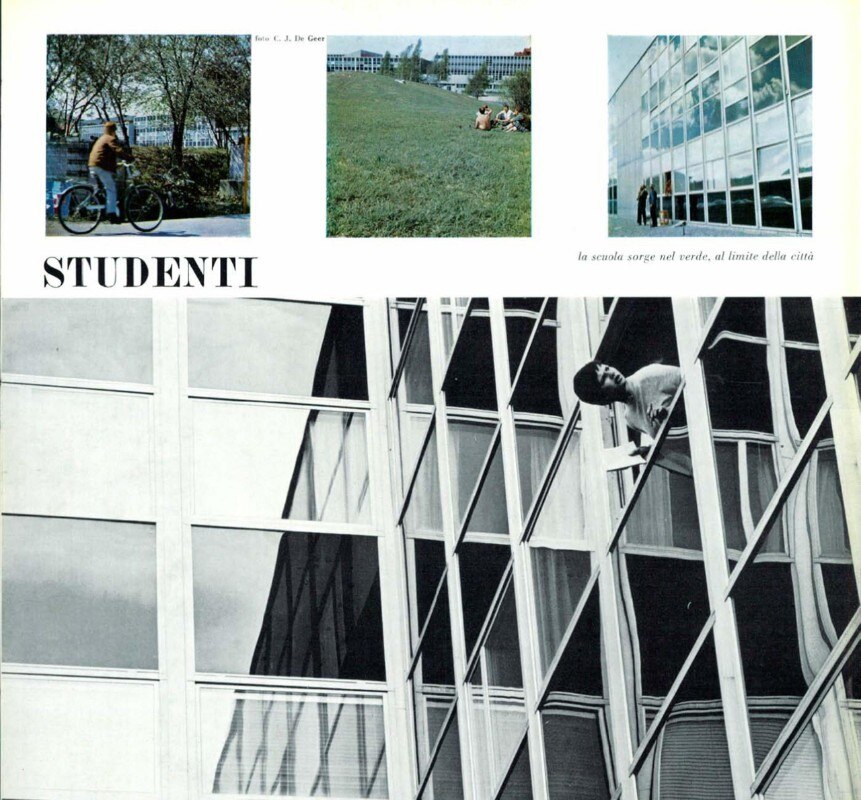

An issue that, on the contrary, already seemed overcome in other parts of the world, like in Sweden. Domus n.421 recognised the achivement of such goal as early as 1964 with a photo report from a Konsfackskolan – School for the arts, crafts and design – in Stockholm.

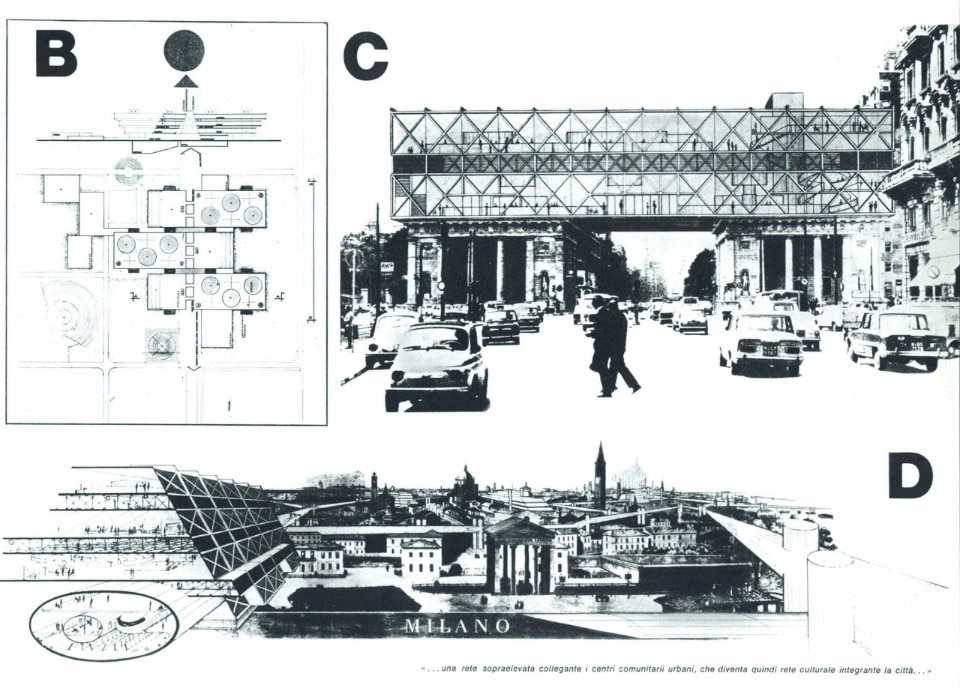

Thus, in this type of school the State is no longer responsible for providing a univocal top-down and "compartmented" education, but the public school itself – to be considered as the togetherness of its students, staff and knowledge – is called contribute to the surrounding community, by providing it with a service.

The replacement of perimetral walls with glass surfaces, mirroring the fluidity of the interiors, is a clear sign of this approach. Similarly, the road connecting the three environments of the school, the entrance, the main body, and the physical education area, becomes the axis of the building. But not only: it is structural in linking the school to other commercial and cultural centres in the area, "creating with them an organic whole".

Over fifty years on from these articles and, mostly, in the light of the evolution of the late-capitalistic society, the enthusiasm showed by Ponti for the prefabricated English schools needs, after all, to be downsized as it now suggests a distinctively corporate-oriented, standardised, and branded idea of education, where empathy is compromised.

Is a building enough to solve the issues on the matter of literacy or, as suggested by Ponti, shall the State provide its student with a broader and more structured support to education? Doesn't this clash with the vision of a "public and not State school" theorised by Rigler, Reibman and D'Urbino? Also, can a school by itself avoid to reproduce the social and cultural disparages afflicting a country without a previous intervention of the State on its society as a whole?

All questions that remain open and that suggest how yesterday's architecture and design can still offer a ground for debate to conceive the society of tomorrow.

Opening image: A student peeks outside the window of the innovative Konsfackskolan in Sotckholm, Domus n. 421, 1964. Photo: Domus Archive