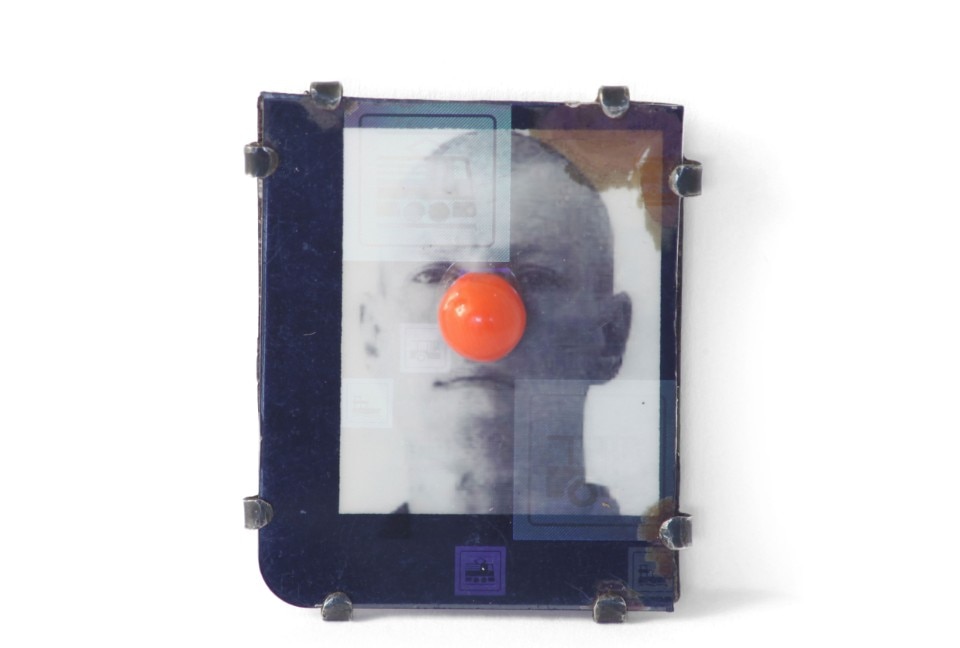

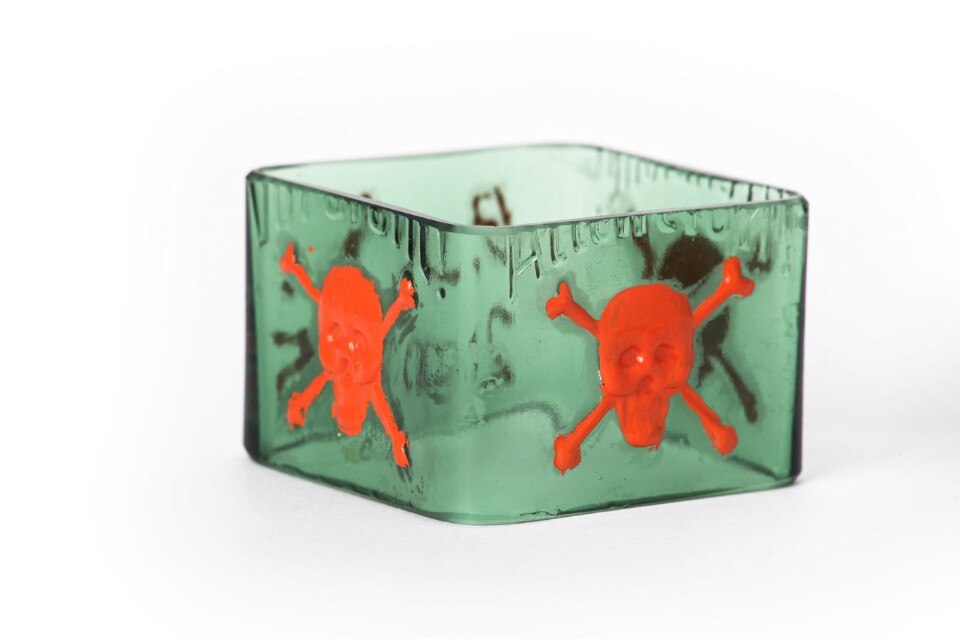

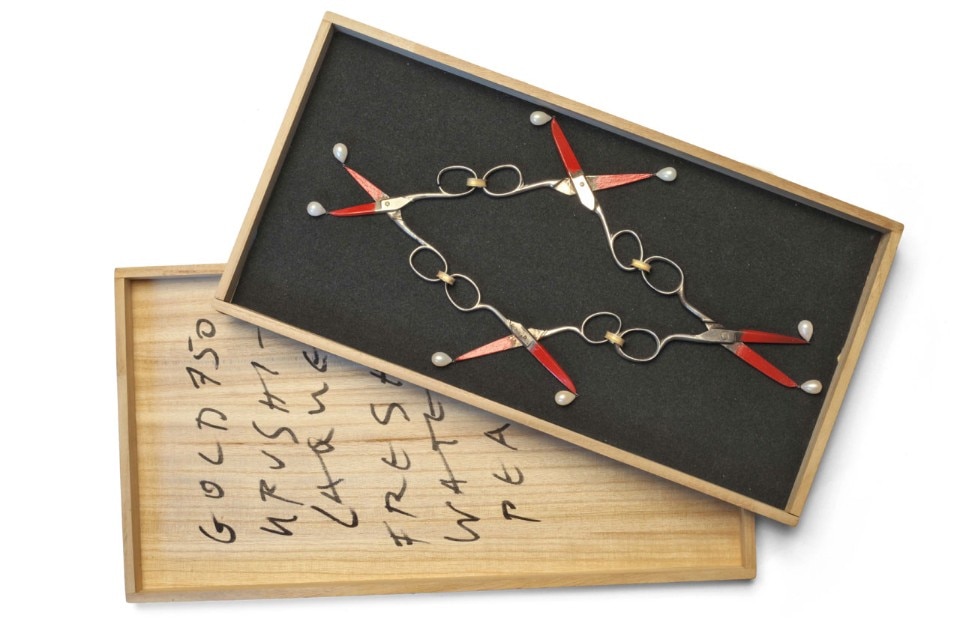

Picking his way across a virtual minefield, the Swiss artist Bernhard Schobinger seeks equilibrium between beauty and ugliness. Born in Zurich in 1946, he has become one of the most important exponents of contemporary jewellery by inserting his craft into the current social discourse. As the same time, his items connect to the archaic origins of amulets. Schobinger reproportions the concept of jewellery as something precious and luxurious. He bypasses the hierarchy of jewellery with evident disesteem regarding its conventional categories. The mounting and modifying of objects of daily use and elementary discards open a creative space in which the functionality and background of objects and materials are called into question. The result is formal richness full of content and (sometimes invisible) meaning, full of humour, imagination, history and destiny. Schobinger has an immediate, sensual relation to materials. We can feel the joy of discovery with which he dissolves the boundaries between applied arts and visual art by combining modest, unusual materials such as shards of glass and nails with metal, gems, pearls and diamonds. Vice versa, he uses precious substances to create objects usually associated with transitoriness and uselessness.

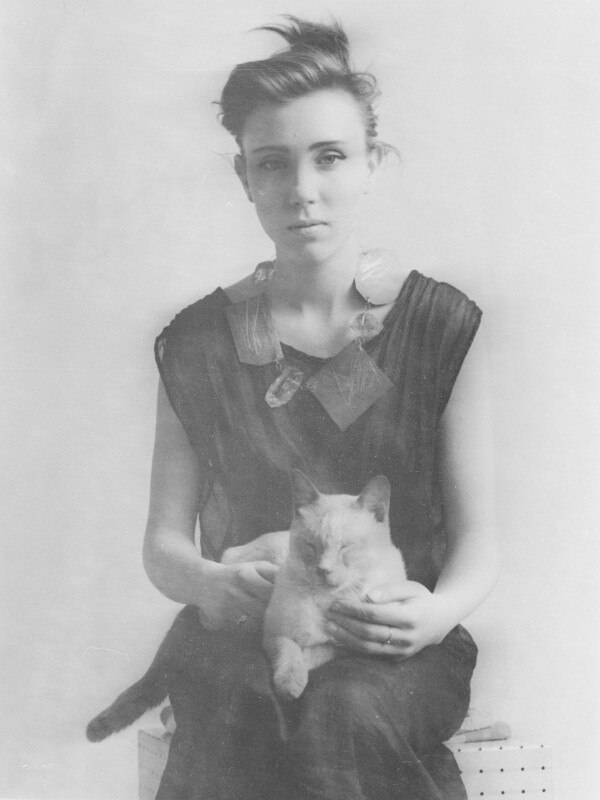

During the Furniture Fair in April 2018, we met with Schobinger at the studio of the Italian painter Turi Simeti (1929) in Milan, which was open to the public for a display of Schobinger's work organised by Simeti’s daughter Martina. This autumn, she is planning to open an exhibition space on Via Tortona in Milan, where the focus will be on showing international artists whose work involves jewellery and other forms of expression considered peripheral that explore the difference between “noble” arts and the applied arts.

Designer jewellery, artistic jewellery, experimental jewellery: these categories seem limiting. What is jewellery?

I have always called myself a goldsmith, and that is indeed what I am. Thanks to Joseph Beuys’s idea that “everybody is an artist” and Paul Feyerabend’s saying, “anything goes”, jewellery design has spread in all directions in a hyper-inflated way. A fatal way of thinking is in vogue, namely: to be creative, you neither need to know anything nor be able to do anything. It has become sufficient to declare an object a work of art, and if possible, give it a pathetically crazy title. Seeing that in this confused situation the term goldsmithing is no longer truthful, some of us look for a conceptual category. Certain textile artists, for example, used to create macramé wall hangings. Now, they fabricate “designer jewellery”. Ironically, I was among those who pushed in favour of the situation as it stands today, breaking down barriers and taboos regarding the use of colour, form, material and technique.

I’m curious to know who wears your pieces. Descendants of Dadaists? Or do you prefer not knowing where your work ends up?

An ornament needs from its owner a high degree of identification, especially when worn, obviously, but this is not my responsibility. The enunciation of my work is “for all and none” as Nietzsche says. It is superindividual and carries an obligation toward our times, the here and now. Some of my objects are on display in the showcases of museums, accessible to whomever interested, alongside evidence of distant civilisations, cultures and eras. They show them next to objects from the Palaeolithic made by Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals, or next to artefacts by Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, Etruscans, Celts, Goths, Incas, Mayas and the inhabitants of the Trobriand Islands.

Your love of your mother tongue, German, is evident. Are your titles part of the work? Do they not risk being lost in translation?

When I was 16 and a student of applied arts, I discovered Paul Klee and was deeply impressed by the extraordinary assonance between the titles and the paintings and drawings. The poetic analogy between language and image reinforces the impression of the whole, like happens in a Gesamtkunstwerk, where the whole is not just the sum of the parts, but something more complex. In my work, linguistic analogies are present in an entirely involuntary and random way. See the necklace Flaschen–Hals–Kette (bottle–neck–chain). It’s a play on the words bottleneck (Flaschenhals) and neck chain (Halskette). Other titles are connected to reminiscences of punk and new wave music, or are ironic and sociopolitical slogans: Nur sauber gekämmt sind wir wirklich frei! (Only when our hair is neatly combed are we truly free!) or Holiday in Cambodia. Sometimes the play on words is untranslatable in other languages.